Triphenylene

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name Triphenylene[1] | |

| Other names Benzo[l]phenanthrene 9,10-Benzophenanthrene 1,2,3,4-Dibenzonaphthalene Isochrysene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.005.385 |

| EC Number |

|

| KEGG | |

| MeSH | C009590 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C18H12 | |

| Molar mass | 228.294 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | white |

| Density | 1.308 g/cm3[2] |

| Melting point | 198 °C; 388 °F; 471 K |

| Boiling point | 438 °C; 820 °F; 711 K |

| -156.6·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

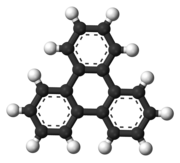

Triphenylene is an organic compound with the formula (C6H4)3. It's a flat polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) that has a highly symmetric and planar structure consists of four fused benzene rings.[3] Triphenylene has delocalized 18-π-electron systems based on a planar structure, corresponding to the symmetry group D3h. It is more resonance stable than its isomers chrysene, benz[a]anthracene, benzo[c]phenanthrene, and tetracene, hence resists hydrogenation.[4] It is a light yellow powder, insoluble in water.[5][6]

Triphenylene serves as a fundamental building block in discotic liquid crystals, where its planar, disc-like structure facilitates the formation of columnar mesophases, enabling applications in organic electronics.[7]

Discovery and First Synthesis

Triphenylene was first separated by German Chemists Von E. Schmidt and G. Schultz in 1880 from the pyrotic product of the thermal decomposition of benzene vapor.[8] Though triphenylene is previously referred to as chrysene, Schmidt and Schultz realized that it is an isomer of chrysene, and successfully identified and named it as triphenylene.[9]

Later in 1907, Carl Mannich first synthesized triphenylene through a two-step reaction from cyclohexanone and confirmed its planar structure.[8] Through predicted condensation of cyclohexanone following the pathway below, he obtained dodecahydrotriphenylene(C18H30).[10]

Mannich then dehydrogenated dodecahydrotriphenylene into triphenylene with two methods: zinc dust distillation and copper-catalyzed dehydrogenation. He confirmed the product was identical to the pyrolysis product from benzene by reproducing Schmidt and Schultz's experiment and comparing the samples. Mannich also characterized triphenylene's properties, derivatives, and oxidation reactions, and confirmed it as a fully aromatic polycyclic hydrocarbon.[10]

Preparation

Triphenylene can be isolated from coal tar. It can also be synthesized in various ways.

One method is trimerization of benzyne.[11] This pathway first diazotizes and iodinates o-bromoaniline through HCl, NaNO2, and KI to produce o-bromoiodobenzene with a yield of 72 - 83%. Then form o-bromophenyl lithium using Li and ether. Add benzene to the organolithium intermediate to get triphenylene with a yield of 53 - 59%. Impurities of biphenyl are then removed with steam distillation.[12]

Another method involves trapping benzyne with a biphenyl derivative.[13] This method started with removing the trimethylsilyl group from 2-(trimethylsilyl)phenyl trifluoromethanesulfonate using cesium fluoride, generating benzyne. Benzyne then reacts with 2-bromobiphenyl in the presence of Pd(dba)₂ and tri(o-tolyl)phosphine as catalysts and produces triphenylene with a yield of 76%.[14]

Application

Discotic liquid crystal and organic electronics

Triphenylene and its derivatives have been widely used in discotic liquid crystal and organic electronics as the core moiety due to its robust discotic molecular architecture. [15][16][17]

Due to its planar structure and π-conjugated system, triphenylene has a rigid discotic structure. This enables it to self-assemble and form highly ordered, long, cylindrical columns.[15] The columnar mesophases provide a direct pathway for charge carriers(electrons or holes) and avoid interruption from scattering and trapped effects in disordered materials. This leads to efficient charge transport along the stacking direction.[18] Tripenylene derivatives, with flexible aliphatic side chains, can modulate intermolecular interactions. This maintains molecular mobility under a wide temperature range and avoids excessive crystallization, and corresponding bad processability and solubility.[15] Triphenylene derivatives also can be synthesized through well-established routes like the Suzuki–Miyaura cross-coupling reaction. Its functional groups can be introduced easily and used to adjust its properties.[19]

Recent studies synthesized new polymer structures incorporating triphenylene units and found that these materials exhibit high photoluminescence and electroluminescence efficiencies. Their emission spectra are well-suited for blue light applications, demonstrating stability and promising performance for next-generation blue emitters.[16]

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs)

Due to its delocalized system, rigid structure, stability, and adjustable structures, triphenylene can be used in the synthesis of Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs).[20][21] Similar to the properties mentioned in DLC applications, triphenylene and its derivatives have high conductivity, and further affect the conductivity of MOFs and COFs.[21] HATP-based 2D MOFs Ni3(HITP)2 single crystals can reach conductivities as high as 150 S/cm at 0K.[20]

The rigid planer structure and three-fold symmetry of triphenylene also make it suitable for honeycomb-like 2D layered materials. This enables supramolecular interlayer aggregation of TP-based MOFs and COFs and increases the stability and conductivity of the structure. It will also create uniform nanopores, which lead to high porosity and facilitate gas storage, molecular sieving, and ion exchange.[21]

Multiple substitution sites of triphenylene bring multifunctionality to TP-base MOFs and COFs. Depending on the different functional groups, the physical and chemical properties of frameworks can be modified easily.[20] In addition, due to the high chemical stability of triphenylene, it is adaptable to various synthesis methods like solvothermal synthesis, layer-by-layer assembly, microfluidic synthesis, interfacial synthesis, etc.[21]

References

- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2014). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 209. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ Ahmed, F. R.; Trotter, J. (1963). "The crystal structure of triphenylene". Acta Crystallographica. 16 (6): 503–508. Bibcode:1963AcCry..16..503A. doi:10.1107/S0365110X63001365.

- ^ Buess, Charles M.; Lawson, D. David (2002-05-01). "The Preparation, Reactions, and Properties of Triphenylenes". ACS Publications. doi:10.1021/cr60206a001?casa_token=7kep1v7_g58aaaaa:unm--ifuidwnir3xz8cf-oqauuma082ej8w7llq_i4otah7vpqnqbaputlfqnf2zvh5dyhfxqo17iwoe. Retrieved 2025-02-19.

- ^ Kofman, V.; Sarre, P.J.; Hibbins, R.E.; ten Kate, I.L.; Linnartz, H. (2017). "Laboratory spectroscopy and astronomical significance of the fully-benzenoid PAH triphenylene and its cation". Molecular Astrophysics. 7: 19–26. Bibcode:2017MolAs...7...19K. doi:10.1016/j.molap.2017.04.002. hdl:1887/58655. S2CID 67834616.

- ^ "Triphenylene - Hazardous Agents | Haz-Map". haz-map.com. Retrieved 2025-02-19.

- ^ PubChem. "Triphenylene". pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2025-02-19.

- ^ Tao, Lei; Xie, Yang; Zhao, Ke-Xiao; Hu, Ping; Wang, Bi-Qin; Zhao, Ke-Qing; Bai, Xiao-Yan (2024-07-01). "Triphenylene trimeric discotic liquid crystals: synthesis, columnar mesophase and photophysical properties". New Journal of Chemistry. 48 (26): 12006–12014. doi:10.1039/D4NJ01693A. ISSN 1369-9261.

- ^ a b Buess, Charles M.; Lawson, D. David (2002-05-01). "The Preparation, Reactions, and Properties of Triphenylenes". ACS Publications. doi:10.1021/cr60206a001?casa_token=7kep1v7_g58aaaaa:unm--ifuidwnir3xz8cf-oqauuma082ej8w7llq_i4otah7vpqnqbaputlfqnf2zvh5dyhfxqo17iwoe. Retrieved 2025-02-19.

- ^ Schmidt, H.; Schultz, G. (1880). "II. Ueber Diphenylbenzole". Justus Liebigs Annalen der Chemie. 203 (1–2): 118–137. doi:10.1002/jlac.18802030107. ISSN 1099-0690.

- ^ a b Mannich, C. (1907). "Über die Kondensation des Cyclohexanons". Berichte der deutschen chemischen Gesellschaft. 40 (1): 153–165. doi:10.1002/cber.19070400122. ISSN 1099-0682.

- ^ Heaney, H.; Millar, I. T. (1960). "Triphenylene". Organic Syntheses. 40: 105. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.040.0105.

- ^ Heaney, H.; Millar, I. T. (1960). "Triphenylene". Organic Syntheses. 40: 105. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.040.0105.

- ^ Katie A. Spence, Milauni M. Mehta, Neil K. Garg (2022). "Synthesis of Triphenylene via the Palladium–Catalyzed Annulation of Benzyne". Organic Syntheses. 99: 174–189. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.099.0174. S2CID 250383238.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Katie A. Spence, Milauni M. Mehta, Neil K. Garg (2022). "Synthesis of Triphenylene via the Palladium–Catalyzed Annulation of Benzyne". Organic Syntheses. 99: 174–189. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.099.0174. S2CID 250383238.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Tao, Lei; Xie, Yang; Zhao, Ke-Xiao; Hu, Ping; Wang, Bi-Qin; Zhao, Ke-Qing; Bai, Xiao-Yan (2024-07-01). "Triphenylene trimeric discotic liquid crystals: synthesis, columnar mesophase and photophysical properties". New Journal of Chemistry. 48 (26): 12006–12014. doi:10.1039/D4NJ01693A. ISSN 1369-9261.

- ^ a b Saleh, Moussa; Park, Young-Seo; Baumgarten, Martin; Kim, Jang-Joo; Müllen, Klaus (2009). "Conjugated Triphenylene Polymers for Blue OLED Devices". Macromolecular Rapid Communications. 30 (14): 1279–1283. doi:10.1002/marc.200900332. ISSN 1521-3927.

- ^ Hoang, Mai Ha; Cho, Min Ju; Kim, Kyung Hwan; Cho, Mi Yeon; Joo, Jin-soo; Choi, Dong Hoon (2009-11-30). "New semiconducting multi-branched conjugated molecules based on π-extended triphenylene and its application to organic field-effect transistor". Thin Solid Films. 8th International Conference on Nano-Molecular Electronics. 518 (2): 501–506. doi:10.1016/j.tsf.2009.07.030. ISSN 0040-6090.

- ^ Wöhrle, Tobias; Wurzbach, Iris; Kirres, Jochen; Kostidou, Antonia; Kapernaum, Nadia; Litterscheidt, Juri; Haenle, Johannes Christian; Staffeld, Peter; Baro, Angelika; Giesselmann, Frank; Laschat, Sabine (2016-02-10). "Discotic Liquid Crystals". Chemical Reviews. 116 (3): 1139–1241. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00190. ISSN 0009-2665.

- ^ "Suzuki-Miyaura Coupling". Chemistry LibreTexts. 2016-12-17. Retrieved 2025-02-19.

- ^ a b c Contreras-Pereda, Noemí; Pané, Salvador; Puigmartí-Luis, Josep; Ruiz-Molina, Daniel (2022-06-01). "Conductive properties of triphenylene MOFs and COFs". Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 460: 214459. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214459. ISSN 0010-8545.

- ^ a b c d Contreras Pereda, Noemí (2021). Synthesis and electronic characterization of triphenylene-based materials (Thesis).

External links

- Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Structure Index Archived 2008-02-15 at the Wayback Machine