Polonnaruwa period

| Polonnaruwa period | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1017–1232 | |||

| |||

| Including | |||

| Monarch(s) | |||

Chronology

| |||

| History of Sri Lanka | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

| Chronicles | ||||||||||||||||

| Periods | ||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| By Topic | ||||||||||||||||

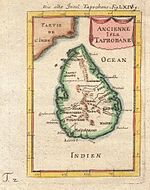

The Polonnaruwa period was a period in the history of Sri Lanka from 1017, after the Chola conquest of Anuradhapura and when the center of administration was moved to Polonnaruwa, to the end of the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa in 1232.

The Kingdom of Polonnaruwa was the second major Sinhalese kingdom of Sri Lanka. It lasted from 1055 under Vijayabahu I until 1212 under the rule of Lilavati. The Kingdom of Polonnaruwa came after the Anuradhapura Kingdom, which was invaded by Chola forces under Rajaraja I. It also followed the Kingdom of Ruhuna, in which the Sinhalese Kings ruled during Chola occupation.

Overview

Periodization of Sri Lanka history:

| Dates | Period | Period | Span (years) | Subperiod | Span (years) | Main government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 300,000 BP–~1000 BC | Prehistoric Sri Lanka | Stone Age | – | 300,000 | Unknown | |

| Bronze Age | – | |||||

| ~1000 BC–543 BC | Iron Age | – | 457 | |||

| 543 BC–437 BC | Ancient Sri Lanka | Pre-Anuradhapura | – | 106 | Monarchy | |

| 437 BC–463 AD | Anuradhapura | 1454 | Early Anuradhapura | 900 | ||

| 463–691 | Middle Anuradhapura | 228 | ||||

| 691–1017 | Post-classical Sri Lanka | Late Anuradhapura | 326 | |||

| 1017–1070 | Polonnaruwa | 215 | Chola conquest | 53 | ||

| 1055–1232 | 177 | |||||

| 1232–1341 | Transitional | 365 | Dambadeniya | 109 | ||

| 1341–1412 | Gampola | 71 | ||||

| 1412–1592 | Early Modern Sri Lanka | Kotte | 180 | |||

| 1592–1739 | Kandyan | 223 | 147 | |||

| 1739–1815 | Nayakkar | 76 | ||||

| 1815–1833 | Modern Sri Lanka | British Ceylon | 133 | Post-Kandyan | 18 | Colonial monarchy |

| 1833–1948 | 115 | |||||

| 1948–1972 | Contemporary Sri Lanka | Sri Lanka since 1948 | 77 | Dominion | 24 | Constitutional monarchy |

| 1972–present | Republic | 53 | Unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic |

Political history

Chola conquest (1017–1070)

A partial consolidation of Chola power in Rajarata had succeeded the initial season of plunder. With the intention to transform Chola encampments into more permanent military enclaves, Saivite temples were constructed in Polonnaruva and in the emporium of Mahatittha. Taxation was also instituted, especially on merchants and artisans by the Cholas.[1] In 1014 Rajaraja I died and was succeeded by his son Rajendra Chola I, perhaps the most aggressive king of his line. Chola raids were launched southward from Rajarata into Rohana. By his fifth year, Rajendra claimed to have completely conquered the island. The whole of Anuradhapura including the south-eastern province of Rohana were incorporated into the Chola Empire.[2] As per the Sinhalese chronicle Mahavamsa, the conquest of Anuradhapura was completed in the 36th year of the reign of the Sinhalese monarch Mahinda V, i.e. about 1017–18.[2] But the south of the island, which lacked large an prosperous settlements to tempt long-term Chola occupation, was never really consolidated by the Chola. Thus, under Rajendra, Chola predatory expansion in Sri Lanka began to reach a point of diminishing returns.[1] According to the Culavamsa and Karandai plates, Rajendra Chola led a large army into Anuradhapura and captured Mahinda V's crown, queen, daughter, vast amount of wealth and the king himself whom he took as a prisoner to India, where he eventually died in exile in 1029.[3][2] After the death of Mahinda V the Sinhalese monarchy continued to rule from Rohana until the Sinhalese kingdom was re-established in the north by Vijayabāhu I. Mahinda V was succeeded by his son Kassapa VI (1029–1040).[4][3]

Polonnaruwa period (1055–1232)

Following a long war of liberation Vijayabāhu I successfully expelled the Cholas out of Sri Lanka as Chola determination began to gradually falter. Vijayabāhu possessed strategic advantages, even without a unified "national" force behind him. A prolonged war of attrition was of greater benefit to the Sinhalese than to the Cholas. After the accession of Virarajendra Chola (1063–1069) to the Chola throne, the Cholas were increasingly on the defensive, not only in Sri Lanka, but also in peninsular India, where they were hard-pressed by the attacks of the Chalukyas from the Deccan.[5] Vijayabāhu launched a successful two-pronged attack upon Anuradhapura and Polonnaruva, when he could finally establish a firm base in southern Sri Lanka. Anuradhapura quickly fell and Polonnaruva was captured after a prolonged siege of the isolated Chola forces.[3][6] Virarajendra Chola was forced to dispatch an expedition from the mainland to recapture the settlements in the north and carry the attack back into Rohana, in order to stave off total defeat. What had begun as a profitable incursion and occupation was now deteriorating into desperate attempts to retain a foothold in the north. After a further series of indecisive clashes the occupation finally ended in the withdrawal of the Cholas. By 1070 when Sinhalese sovereignty was restored under Vijayabāhu I, he had reunited the country for the first time in over a century.[7][8][6]

Vijayabāhu I (1055–1110), descended from, or at least claimed to be descended from the House of Lambakanna II. He crowned himself in 1055 at Anuradhapura but continued to have his capital at Polonnaruwa for it being more central and made the task of controlling the turbulent province of Rohana much easier.[9] Aside from leading the prolonged resistance to Chola rule Vijayabāhu I proved to be outstanding in administration and economic regeneration after the war and embarked on the rehabilitation of the island's irrigation network and the resuscitation of Buddhism in the country.[6] Buddhism had suffered severely in the country during the Chola rule, where precedence was given to Saivite Hinduism.[10] The influnece of Hinduism on religion and society during this period also saw a hardening of caste attitudes in the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa.[11] Economic, Social structure, art and architecture of the Kingdom of Polonnaruwa was a continuation and development of that of the Anuradhapura period. Internal and external trade made the kingdom more prosperous than just relying on its primarily agricultural economy.[12] Seafaring crafts were built in Sri Lanka and were known to have sailed as far as China, some may have even been used as troop transport ships to Burma. Howevere those used in External trade were mostly of foreign construction.[13] The island's importance as an important center of international trade attracted many foreign merchants, the most prominent of which were descendants of Arab traders. The south of India also hosted settlements of these Arab merchants, and they would become a dominant influence on the country's external trade, but by no means was a monopoly.[13]

Upon Vijayabāhu I's death a succession dispute jeopardized the recovery from the Chola conquest. His successors proved unable to consolidate power plunging the kingdom into a period of civil war, from which Parākramabāhu I (1153–1186), a closely related royal emerged.[15] Parākramabāhu I established control over the island and secured his recognition as Vijayabāhu's heir by obtaining the Tooth and bowl relics of the Buddha, which by now had become essential to the legitimacy of royal authority in Sri Lanka.[15]

By the time of the Polonnaruwa period the Sinhalese has centuries of experience in irrigation technology behind them and so the Polonnaruwa kings, especially Parākramabāhu the Great, made distinguished contributions of their own at honing these techniques to cope with the special requirements of the immense irrigation projects at the time.[16] Sri Lanka's irrigation network was extensively expanded during the reign of Parākramabāhu the Great.[17] He built 1470 reservoirs – the highest number by any ruler in Sri Lanka's history – repaired 165 dams, 3910 canals, 163 major reservoirs, and 2376 mini-reservoirs.[17] His most famous construction is the Parakrama Samudra, the largest irrigation project of medieval Sri Lanka. Having re-established the political unification of the island, Parākramabāhu continued Vijayabāhu policy in keeping a tight check on separatist tendencies within the island, especially in Rohana where particularism was a deeply ingrained political tradition. Parākramabāhu faced a formidable rebellion in 1160 as Rohana did not accept its loss of autonomy lightly. A rebellion in 1168 in Rajarata also manifested. Both were put down with great severity and all vestiges of its former autonomy purposefully eliminated. Particularism was now much less tolerated than it was during the Anuradhapura period. This new over-centralization of authority in Polonnaruwa would however work against the Sinhalese in the future and the country would eventually pay dearly as a result.[18]

Parākramabāhu's reign is memorable for two major campaigns – in the south of India as part of a Pandyan war of succession, and a punitive strike against the kings of Ramanna (Myanmar) for various perceived insults to Sri Lanka.[19][20] Parākramabāhu I was the last of the great ancient Sri Lankan kings.[18] His reign is considered as a time when Sri Lanka was at the height of its power.[21][20] Parākramabāhu had no sons, which complicated the problem of succession upon his death. Amid the succession crisis a scion of a foreign dynasty, Niśśaṅka Malla established his claims as a Prince of Kalinga,[note 2] claiming to be chosen and trained for the succession by Parākramabāhu himself.[18] He was also either the son-in-law or nephew of Parākramabāhu.[22]

Niśśaṅka Malla (1187–1196) was the first monarch of the House of Kalinga and the only Polonnaruwa monarch to rule over the whole island after Parākramabāhu. His reign gave the country a brief decade of order and stability before the speedy and catastrophic break-up of the hydraulic civilisations of the dry zone.[18] With his death there was a renewal of political dissension, now complicated by dynastic disputes.[23] Though he and his predecessors Vijayabāhu and Parākramabāhu achieved much in state building. The conspicuous lack of restraint, especially that of Parākramabāhu, in combination with an ambitious and venturesome foreign policy, and an expensive diversion of state resources towards public works projects, sapped the strength of the country and contributed to its sudden and complete collapse.[18]

The House of Kalinga would maintain itself in power, but only with the support of an influential faction within the country. Their survival owed much to the inability of the factions opposing them to come up with an aspirant to the throne with a politically viable claim, or sufficient durability once installed in power, therefore the House of Kalinga's hold on the throne was inherently precarious. On three occasions, the queen of Parākramabāhu, Lilāvatī, was raised to the throne out of desperation.[23] The factional struggle and political instability attracted the attention of South Indian adventures bent on plunder, culminating in the devastating campaign of pillage under Māgha of Kalinga (1215–1236), claiming the inheritance of the kingdom through his kinsman who reigned before.[24][23]

Māgha, a bigoted Hindu, persecuted Buddhists, despoiling the temples and giving away lands of the Sinhalese to his followers.[24] His priorities in ruling were to extract as much as possible from the land and overturn as many of the traditions of Rajarata as possible. His reign saw the massive migration of the Sinhalese people to the south and west of Sri Lanka, and into the mountainous interior, in a bid to escape his power.[25] Māgha's rule of 21 years and its aftermath are a watershed in the history of the island, creating a new political order.[23] After his death in 1255 Polonnaruwa ceased to be the capital, Sri Lanka gradually decayed in power and from then on there were two, or sometimes three rulers existing concurrently.[23][26] Parakramabahu VI of Kotte (1411–1466) would be the only other Sinhalese monarch to establish control over the whole island after this period.[23] The Rajarata, the traditional location of the Sinhalese kingdom and Rohana, the previously autonomous subregion were abandoned. Two new centers of political authority emerged as a result of the fall of the Polonnaruwa kingdom.

In the face of repeated South Indian invasions the Sinhalese monarchy and people retreated into the hills of the wet zone, further and further south, seeking primarily security. The capital was abandoned and moved to Dambadeniya by Vijayabāhu III establishing the Dambadeniya era of the Sinhalese kingdom.[27][28] A second poilitical center emerged in the north of the island where Tamil settlers from previous Indian incursions occupied the Jaffna Peninsula and the Vanni.[note 3] Many Tamil members of invading armies, mercenaries, joined them rather than returning to India with their compatriots. By the 13th century the Tamils too withdrew from the Vanni almost entirely into the Jaffna peninsula where an independent Tamil kingdom had been established.[26][25]

See also

Notes

- ^ Considered as one of the oldest Hindu shrine in Polonnaruwa founded during Chola occupation built during 1015-1044[14]

- ^ The birthplace of Prince Vijaya and the ancestors of the Sinhalese.

- ^ The land between Anuradhapura and Jaffna

References

Citations

- ^ a b Spencer 1976, p. 416.

- ^ a b c Sastri 1935, p. 199–200.

- ^ a b c Spencer 1976, p. 417.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 741.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 81-2.

- ^ a b c De Silva 2005, p. 82.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 57.

- ^ Lambert 2014.

- ^ Sastri 1935, p. 172–173.

- ^ Bokay 1966, p. 93–95.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 96.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 92.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 99.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 105.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 83.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 93.

- ^ a b Herath 2002, p. 19.

- ^ a b c d e De Silva 2005, p. 84.

- ^ International Lake Environment Committee 2011.

- ^ a b ParakramaBahu I: 1153 - 1186 Eighth massa 2019.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 64.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 65.

- ^ a b c d e f De Silva 2005, p. 85.

- ^ a b Codrington 1926, p. 67.

- ^ a b Indrapala 1969, p. 16.

- ^ a b De Silva 2005, p. 87.

- ^ Codrington 1926, p. 76.

- ^ De Silva 2005, p. 110.

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Oldenberg, Hermann, ed. (1879). The Dîpavaṃsa: An Ancient Buddhist Historical Record. London & Edinburgh: Williams and Norgate.

- Mahānāma; tr. Geiger, Wilhelm; tr. Bode, Mabel Haynes (1912). The Mahāvaṃsa, Or, The Great Chronicle of Ceylon. London: Oxford University Press.

- Dhammakitti; Ger tr. Geiger, Wilhelm; Eng tr. Rickmers, Christian Mabel (1929). Cūḷavaṃsa: Being the More Recent Part of the Mahāvaṃsa, Part 1. London: Oxford University Press.

- Gunasekara, B., ed. (1900). The Rajavaliya: Or a Historical Narrative of Sinhalese Kings. Colombo: George J. A. Skeen, Government Printer, Ceylon.

- Knox, Robert (1681). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon. London: Richard Chiswell.

Secondary sources

- Histories

- Parker, Henry (1909). Ancient Ceylon. London: Luzac & Co.

- Codrington, H. W. (1926). A Short History Of Ceylon. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Senaveratna, John M. (1930). The Story of the Sinhalese from the Most Ancient Times Up to the End of "the Mahavansa" Or Great Dynasty: Vijaya to Maha Sena, B.C. 543 to A.D.302. Colombo: W. M. A. Wahid & Bros. ISBN 9788120612716.

- Blaze, L. E. (1933). History of Ceylon (PDF) (Eighth ed.). Colombo: Christian literature society for India and Africa.

- Nicholas, Cyril Wace; Paranavitana, Senerat (1961). A Concise History of Ceylon: From the Earliest Times to the Arrival of the Portuguese in 1505. Ceylon University Press.

- Deraniyagala, S. U. (December 1992). The Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective (1st ed.). Department of Archaeological Survey, Government of Sri Lanka. ISBN 9789559159001.

- de Silva, K. M. (1981). A History of Sri Lanka. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520043206.

- Siriweera, W. I. (2002). History of Sri Lanka: From Earliest Times Up to the Sixteenth Century. Dayawansa Jayakody & Company. ISBN 9789555512572.

- de Silva, K. M. (2005). A History of Sri Lanka. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa Publications. ISBN 9789558095928.

- Peebles, Patrick (2006). The History of Sri Lanka. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 9780313332050.

- Other Books

- All Ceylon Buddhist Congress (1956). The Betrayal of Buddhism: An Abridged Version of the Report of the Buddhist Committee of Inquiry. Dharmavijaya Press.

- European Association of Social Anthropologists (2001). Schmidt, Bettina E.; Schroeder, Ingo W. (eds.). Anthropology of Violence and Conflict. Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415229050.

- Institute for International Studies (Peradeniya, Sri Lanka) (1992). Jayasekera, P. V. J. (ed.). Security dilemma of a small state. South Asian Publishers. ISBN 9788170031482.

- Anthonisz, Richard Gerald (2003). The Dutch in Ceylon: An Account of Their Early Visits to the Island, Their Conquests, and Their Rule Over the Maritime Regions During a Century and a Half. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 9788120618459.

- Arseculeratne, S. N. (1991). Sinhalese Immigrants in Malaysia & Singapore, 1860-1990: History Through Recollections. Colombo: K.V.G. De Silva & Sons. ISBN 9789559112013.

- Aves, Edward (2003). Sri Lanka. Footprint. ISBN 9781903471784.

- Bandaranayake, S. D. (1974). Sinhalese Monastic Architecture: The Viháras of Anurádhapura. BRILL. ISBN 9789004039926.

- Bandaranayake, Senaka; Madhyama Saṃskr̥tika Aramudala (1999). Sigiriya: city, palace, and royal gardens. Central Cultural Fund, Ministry of Cultural Affairs. ISBN 9789556131116.

- Bond, George Doherty (1992). The Buddhist Revival in Sri Lanka: Religious Tradition, Reinterpretation and Response. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120810471.

- Bosma, Ulbe; Raben, Remco (2008). Being "Dutch" in the Indies: A History of Creolisation and Empire, 1500-1920. Singapore: NUS Press. ISBN 9789971693732.

- Brohier, Richard Leslie (1933). The Golden Age Of Military Adventure In Ceylon 1817-1818. Colombo: Plâté limited.

- Brown, Michael Edward; Ganguly, Sumit (2003). Fighting Words: Language Policy and Ethnic Relations in Asia. MIT Press. ISBN 9780262523332.

- Chattopadhyaya, Haraprasad (1994). Ethnic Unrest in Modern Sri Lanka: An Account of Tamil-Sinhalese Race Relations. M.D. Publications Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9788185880525.

- Crusz, Noel (2001). The Cocos Islands Mutiny. Freemantle Arts Centre Press. ISBN 9781863683104.

- De Silva, R. Rajpal Kumar (1988). Illustrations and Views of Dutch Ceylon 1602-1796: A Comprehensive Work of Pictorial Reference With Selected Eye-Witness Accounts. Brill Archive. ISBN 9789004089792.

- Dharmadasa, K. N. O. (1992). Language, Religion, and Ethnic Assertiveness: The Growth of Sinhalese Nationalism in Sri Lanka. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472102884.

- Garg, Gaṅgā Rām (1992). Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World. Concept Publishing Company. ISBN 9788170223757.

- Gunaratna, Rohan (1998). Sri Lanka's Ethnic Crisis & National Security. South Asia Network on Conflict Research. ISBN 9789558093009.

- Gunawardena, Charles A. (2005). Encyclopedia of Sri Lanka. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 9781932705485.

- Herath, R. B. (2002). Sri Lankan Ethnic Crisis: Towards a Resolution. Trafford Publishing. ISBN 9781553697930.

- Hoffman, Bruce (2006). Inside Terrorism. New York City: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231126991.

- Holt, John (1991). Buddha in the Crown: Avalokiteśvara in the Buddhist Traditions of Sri Lanka. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195064186.

- Holt, John (2011). The Sri Lanka Reader: History, Culture, Politics. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822349822.

- Irons, Edward A. (2008). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Facts on File. ISBN 9780816054596.

- Jayasuriya, J. E. (1981). Education in the Third World: Some Reflections. Somaiya.

- Keshavadas, Sadguru Sant (1988). Ramayana at a Glance. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. ISBN 9788120805453.

- Kulke, Hermann; Kesavapany, K.; Sakhuja, Vijay (2009). Nagapattinam to Suvarnadwipa: Reflections on the Chola Naval Expeditions to Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 9789812309372.

- Liyanagamage, Amaradasa (1968). The Decline of Polonnaruwa and the Rise of Dambadeniya (circa 1180 - 1270 A.D.). Department of Cultural Affairs.

- Mendis, Ranjan Chinthaka (1999). The Story of Anuradhapura: Capital City of Sri Lanka from 377 BC - 1017 Ad. Lakshmi Mendis. ISBN 9789559670407.

- Mills, Lennox A. (1964). Ceylon Under British Rule, 1795-1932. Cass. ISBN 9780714620190.

- Mittal, J. P. (2006). History Of Ancient India (a New Version)From 4250 BC To 637 AD. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. ISBN 9788126906161.

- Mittermeier, Russell A.; Mittermeier, Cristina Goettsch; Myers, Norman (1999). Hotspots: Earth's Biologically Richest and Most Endangered Terrestrial Ecoregions. CEMEX. ISBN 9789686397581.

- Nubin, Walter (2002). Sri Lanka: Current Issues and Historical Background. Nova Publishers. ISBN 9781590335734.

- Perera, Lakshman S. (2001). The Institutions of Ancient Ceylon from Inscriptions: From 831 to 1016 A.D., pt. 1. Political institutions. International Centre for Ethnic Studies. ISBN 9789555800730.

- Pieris, Paulus Edward (1918). Ceylon and the Hollanders, 1658-1796. Tellippalai: American Ceylon Mission Press.

- Ponnamperuma, Senani (2013). The Story of Sigiriya. Panique Pty, Limited. ISBN 9780987345110.

- Rambukwelle, P. B. (1993). Commentary on Sinhala kingship: Vijaya to Kalinga Magha. P.B. Rambukwelle. ISBN 9789559556503.

- Sarachchandra, B. S. (1977). අපේ සංස්කෘතික උරුමය [Our Cultural Heritage] (in Sinhala). V. P. Silva.

- Siriweera, W. I. (1994). A study of the economic history of pre-modern Sri Lanka. Vikas Pub. House. ISBN 9780706976212.

- Spencer, Jonathan (2002). Sri Lanka: History and the Roots of Conflict. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780203407417.

- Tambiah, Henry Wijayakone (1954). The laws and customs of the Tamils of Ceylon. Tamil Cultural Society of Ceylon.

- Tinker, Hugh (1990). South Asia: A Short History. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824812874.

- Wanasundera, Nanda Pethiyagoda (2002). Sri Lanka. Marshall Cavendish. ISBN 9780761414773.

- Sastri, K. A (1935). The CōĻas. Madras: University of Madras.

- Journals

- Bokay, Mon (1966). "Relations between Ceylon and Burma in the 11th Century A.D". Artibus Asiae. Supplementum. 23. JSTOR: 93–95. doi:10.2307/1522637. JSTOR 1522637.

- Deraniyagala, S. U. (8–14 September 1996). "Pre- and protohistoric settlement in Sri Lanka". XIII U. I. S. P. P. Congress Proceedings. 5. Lanka Library: 277–285.

- Geiger, Wilhelm (July 1930). "The Trustworthiness of the Mahavamsa". The Indian Historical Quarterly. 6 (2). Digital Library & Museum of Buddhist Studies: 205–228.

- Indrapala, K. (1969). "Early Tamil Settlements in Ceylon". The Journal of the Ceylon Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland. 13. JSTOR: 43–63. JSTOR 43483465.

- Kennedy, K. A. R.; Disotell, Todd; Roertgen, W. J.; Chiment, J.; Sherry, J. (1986). "Biological anthropology of Upper Pleistocene Hominids from Sri Lanka: Batadomba Lena and Beli Lena Caves". Ancient Ceylon. 6.

- Paranavitana, S. (1936). "Two Royal Titles of the Early Sinhalese, and the Origin of Kingship in Ancient Ceylon". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 68 (3). JSTOR: 443–462. doi:10.1017/S0035869X0007725X (inactive 23 February 2025). JSTOR 25201355.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of February 2025 (link) - Sivasundaram, Sujit (April 2010). "Ethnicity, Indigeneity, and Migration in the Advent of British Rule to Sri LankaSujit SivasundaramEthnicity, Indigeneity, and Migration in the Advent of British Rule to Sri Lanka". The American Historical Review. 115 (2): 428–452. doi:10.1086/ahr.115.2.428. ISSN 0002-8762.

- Spencer, George W. (1976). "The Politics of Plunder: The Cholas in Eleventh-Century Ceylon". The Journal of Asian Studies. 35 (3). JSTOR: 405–419. doi:10.2307/2053272. JSTOR 2053272.

- Starr, Chester G. (1956). "The Roman Emperor and the King of Ceylon". Classical Philology. 51 (1). JSTOR: 27–30. doi:10.1086/363981. JSTOR 266383. S2CID 161093319.

- Stokke, Kristian; Ryntveit, Anne Kirsti (2000). "The Struggle for Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka. Growth and Change". Growth and Change. 31 (2). ResearchGate: 285–304. doi:10.1111/0017-4815.00129.

- van der Kraan, Alfons (1999). "A Baptism of Fire: The Van Goens Mission to Ceylon and India, 1653-54" (PDF). Journal of the UNE Asia Centre. 2: 1–50. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-05-09.

- Weerakkody, D. P. M. (1987). "Sri Lanka and the Roman Empire". Modern Ceylon Studies. 2 (1 & 2). University of Peradeniya: 21–32.