Serial film

A serial film, film serial (or just serial), movie serial, or chapter play, is a motion picture form popular during the first half of the 20th century, consisting of a series of short subjects exhibited in consecutive order at one theater, generally advancing weekly, until the series is completed. Usually, each serial involves a single set of characters, protagonistic and antagonistic, involved in a single story. The film is edited into chapters, after the fashion of serial fiction, and the episodes should not be shown out of order, as individual chapters, or as part of a random collection of short subjects.

Each chapter was screened at a movie theater for one week, and typically ended with a cliffhanger, in which characters found themselves in perilous situations with little apparent chance of escape. Viewers had to return each week to see the cliffhangers resolved and to follow the continuing story. Movie serials were especially popular with children, and for many youths in the first half of the 20th century a typical Saturday matinee at the movies included at least one chapter of a serial, along with animated cartoons, newsreels, and two feature films.

There were films covering many genres, including crime fiction, espionage, comic book or comic strip characters, science fiction, and jungle adventures. Many serials were Westerns, since those were the least expensive to film. Although most serials were filmed economically, some were made at significant expense. The Flash Gordon serial and its sequels, for instance, were major productions in their times. Serials were action-packed stories that usually involved a hero (or heroes) battling an evil villain and rescuing a damsel in distress. The villain would continually place the hero into inescapable death traps, or the heroine would be placed into a lethal peril and the hero would come to her rescue. The hero and heroine would face one trap after another, battling countless thugs and henchmen, before finally defeating the villain.

History

- List of film serials by year

Birth of the form

Movie serials began in Europe. In France Victorin-Hippolyte Jasset launched his series of Nick Carter films in 1908, and the idea of the episodic crime adventure was developed particularly by Louis Feuillade in Fantômas (1913–14), Les Vampires (1915), and Judex (1916); in Germany, Homunculus (1916), directed by Otto Rippert, was a six-part horror serial about an artificial creature.

There were also the 1910 Deutsche Vitaskop five-episode Arsene Lupin Contra Sherlock Holmes, based upon the Maurice LeBlanc novel,[1] and a possible but unconfirmed Raffles serial in 1911.[2]

American serials

Serials in America first came about in 1912, as extensions of magazine and newspaper stories. Publishers realized they could build interest (and boost circulation) by sponsoring live-action adventures of the printed characters, serialized like the printed counterparts. The first screen adaptation was What Happened to Mary. produced by the Edison studio and coinciding with the adventure stories published in The Ladies' World. It may be significant that the early American serials were aimed at the feminine audience who wanted thrills, not the masculine audience who preferred more extreme, blood-and-thunder action. By the 1930s and the advent of sound films, both markets ultimately devolved to the juvenile audience, although serials continued to command a certain adult following.

The most famous American serials of the silent era include The Perils of Pauline and The Exploits of Elaine made by Pathé Frères and starring Pearl White. Another popular serial was the 119-episode The Hazards of Helen made by Kalem Studios and starring Helen Holmes for the first 48 episodes, then Helen Gibson for the remainder. Ruth Roland, Marin Sais, Grace Cunard, and Ann Little were also early leading serial queens. Other major studios of the silent era, such as Vitagraph and Essanay Studios, produced serials, as did Warner Bros., Fox, and Universal. Several independent companies (for example, Mascot Pictures) made Western serials. Four silent Tarzan serials were also made.

Sound era

Expensive feature films were offered by exhibitors for a percentage of the theaters' admissions. Serials, however, were rented by exhibitors for a much lower, flat fee. The arrival of sound technology made it costlier to produce serials, so that they were no longer as profitable on a flat rental basis. Further, the stock market crash of 1929 and the added expense of sound equipment made it impossible for many of the smaller companies that produced serials to upgrade to sound, and they went out of business. Mascot Pictures, which specialized in serials, made the transition from silent to sound and produced the first "talking" serial, King of the Kongo (1929). Universal Pictures also kept its serial unit alive through the transition.

In the early 1930s a handful of independent companies tried their hand at making serials. The Weiss Brothers had been making serials in 1935 and 1936. In 1937 Columbia Pictures, inspired by the previous year's serial blockbuster success at Universal, Flash Gordon, decided to enter the serial field and contracted with the Weiss Brothers (as Adventure Serials Inc.) to make four chapter plays. They were successful enough that Columbia canceled the agreement after three productions[3] and produced the fourth itself, using its own staff and facilities. Columbia thus forced the Weiss Bros. out of the serial field.

Mascot Pictures was absorbed by Republic Pictures, so that by 1937, serial production was now in the hands of three companies – Universal, Columbia, and Republic. Each company had its own following: Republic was known for its well staged action scenes and spectacular cliffhanger endings; Universal broadened its serials' appeal by casting stars of feature films; Columbia specialized in screen adaptations of radio, comic-book, and detective-fiction adventures.

These studios turned out four serials per year (one each season) of 12 to 15 episodes each, a pace they all kept up until the end of World War II. In 1946, new management at Universal did away with all low-budget productions including "B" musicals, mysteries, westerns, and serials,[4] Republic and Columbia continued unchallenged. Republic's serials ran for 12, 13, 14, or 15 chapters; Columbia's ran a standard 15 episodes (with the single exception of Mandrake the Magician, which ran 12 episodes).

By the mid-1950s, however, episodic television series and the sale of older serials to TV syndicators, together with the gradual drop in audience attendance at Saturday matinees in general, made serial production a losing proposition.

Production

Peak form

The classic sound serial, particularly in its Republic format, has a first episode of three reels (approximately 30 minutes in length) and begins with reports of a masked, secret, or unsuspected villain menacing an unspecific part of America. This episode traditionally has the most detailed credits at the beginning, often with pictures of the actors with their names and that of the character they play. Often there follows a montage of scenes lifted from the cliffhangers of previous serials to depict the ways in which the master criminal was a serial killer with a motive. In the first episode, various suspects or "candidates" who may, in secret, be this villain are presented, and the viewer often hears the voice but does not see the face of this mastermind commanding his lieutenant (or "lead villain"), whom the viewer sees in just about every episode.

In the succeeding weeks (usually 11 to 14), an episode of two reels (approximately 20 minutes) was presented, in which the villain and his henchmen commit crimes in various places, fight the hero, and trap someone to make the ending a cliffhanger. Many of the episodes have clues, dialogue, and events leading the viewer to think that any of the candidates were the mastermind. As serials were made by writing the whole script first and then slicing it into portions filmed at various sites, often the same location would be used several times in the serial, often given different signage, or none at all, just being referred to differently. There would often be a female love interest of the male hero, or a female hero herself, but as the audience was mainly youngsters, there was no romance.

The beginning of each chapter would bring the story up to date by repeating the last few minutes of the previous chapter, and then revealing how the main character escaped. Often the reprised scene would add an element not seen in the previous episode, but unless it contradicted something shown previously, audiences accepted the explanation. On rare occasions the filmmakers would depend on the audience not remembering details of the previous week's chapter, using alternate outcomes that did not exactly match the previous episode's cliffhanger.

The last episode was sometimes a bit longer than most, for its tasks were to unmask the head villain (who usually was someone completely unsuspected), wrap up the loose ends, and end with the victorious principals relieved of their perils.

In 1936, Republic standardized the "economy episode" (or "recap chapter") in which the characters summarize or reminisce about their adventures, so as to introduce showing those scenes again (in the manner of a clip show in modern television). Serials had been including older scenes for years, as flashbacks during later parts of the narrative, but the wholesale insertion of entire sequences was introduced in the 1936 outdoor serial Robinson Crusoe of Clipper Island. It was scheduled as a standard 12-chapter adventure, but when bad weather on location delayed the filming, writer Barry Shipman was forced to come up with two extra chapters to justify the added expense. This was an emergency measure at the time, but Republic recognized that it did save money, so the recap chapter became standard practice in almost all of its ensuing serials. Recap chapters had lower budgets, so rather than staging an elaborate cliffhanger (a runaway vehicle, a stampede, a flooding chamber, etc.), a cheaper, simpler cliffhanger would be employed (an explosion, someone knocked unconscious, etc.).

Production practices

The major studios had their own retinues of actors and writers, their own prop departments, existing sets, stock footage, and music libraries. The early independent studios had none of these, but could rent sets from independent producers of western features.

The firms saved money by reusing the same cliffhangers, stunt and special-effects sequences over the years. Mines or tunnels flooded often, even in Flash Gordon (reusing spectacular flood footage from Universal's 1927 silent drama Perch of the Devil) and the same model cars and trains went off the same cliffs and bridges. Republic had a Packard limousine and a Ford Woodie station wagon used in serial after serial so they could match the shots with the stock footage from the model or previous stunt driving. Three different serials had them chasing the Art Deco sound truck, required for location shooting, for various reasons. Male fistfighters usually wore hats so that the change from actor to stunt double would not be caught so easily. A rubber liner on the hatband of the stuntman's fedora would fit snugly on the stuntman's head, so the hat would stay on during fight scenes.

Recaps of the story

Each serial chapter began with exposition of what led up to the previous episode's cliffhanger. Each studio approached this in different ways. Universal had been using printed title cards to introduce each chapter until 1938, when it began using "scrolling text" , a format George Lucas used in the Star Wars films. In 1942 Universal scrapped the printed recaps altogether in what the studio called "streamlined serials". The action began immediately, with the story characters discussing the action leading up to the cliffhanger.

Republic followed the traditional format established by its predecessor Mascot, with still photos of the story characters accompanied by printed recaps of the narrative.

Columbia used spoken recaps through 1939, replaced by printed recaps in 1940. Announcer Knox Manning was hired in 1940 to read along with the printed recaps until 1942, when only Manning's voice was used to summarize the action.

Stylistic differences between the studios

Universal had been making serials since the 1910s, and continued to service its loyal neighborhood-theater customers with four serials annually. The studio made news in 1929 by hiring Tim McCoy to star in its first all-talking serial, The Indians Are Coming! Epic footage from this western serial turned up again and again in later serials and features. In 1936 Universal scored a coup by licensing the comic-strip character Flash Gordon for the screen; the serial was a smash hit, and was even booked into first-run theaters that usually did not bother with chapter plays. Universal followed it up with more pop-culture icons: The Green Hornet and Ace Drummond from radio, and Smilin' Jack and Buck Rogers from newspapers. Universal was more story-conscious than the other studios, and cast its serials with "name" actors recognizable from feature films: Lon Chaney Jr., Béla Lugosi, Dick Foran, The Dead End Kids, Kent Taylor, Buck Jones, Ralph Morgan, Milburn Stone, Robert Armstrong, Irene Hervey, and Johnny Mack Brown, among many others.

In the 1940s Universal's serials employed urban and/or wartime themes, incorporating newsreel footage of actual disasters. The 1942 serial Gang Busters is perhaps the best of Universal's urban serials; Universal often reused some of its footage for future serials. Don Winslow of the Navy was a popular, patriotic serial. The studio's reliance on stock footage for the big action scenes -- some of it silent footage dating back to the 1920s -- was certainly economical, but it often hurt the overall quality of the films. Universal's last serial was The Mysterious Mr. M (1946), and the serial unit shut down.

Republic was the successor to Mascot Pictures, a serial specialist. Writers and directors were already geared to staging exciting films, and Republic improved on Mascot, adding music to underscore the action, and staging more elaborate stunts. Republic was one of Hollywood's smaller studios, but its serials have been hailed as some of the best, especially those directed by John English and William Witney. In addition to solid screenwriting that many critics thought was quite accomplished, the firm also introduced choreographed fistfights, which often included the stuntmen (usually the ones portraying the villains, never the heroes) throwing things in desperation at one another in every fight to heighten the action. Republic serials are noted for outstanding special effects, such as large-scale explosions and demolitions, and the more fantastic visuals like Captain Marvel and Rocketman flying. Most of the trick scenes were engineered by Howard and Theodore Lydecker. Republic bought the screen rights to the newspaper comic character Dick Tracy, the radio character The Lone Ranger, and the comic-book characters Captain America, Captain Marvel, and Spy Smasher.

Republic's serial scripts were written by teams, usually from three to seven writers. From 1950 Republic economized on serial production. The studio was no longer licensing expensive radio and comic-strip characters, and no longer staging spectacular action sequences. To save money, Republic turned instead to its impressive backlog of action highlights, which were cleverly re-edited into the new serials. The studio slashed costs further by shortening the length of each chapter from 1800 feet (20 minutes) to 1200 feet (13 minutes, 20 seconds). Most of the studio's serials of the 1950s were written by only one man, Ronald Davidson—Davidson had co-written and produced many Republic serials, and was familiar enough with the film library to write new scenes based on the older action footage. Republic's last serial was King of the Carnival (1955), a reworking of 1939's Daredevils of the Red Circle using some of its footage.

Columbia made several serials using its own staff and facilities (1938–1939 and 1943–1945), and these are among the studio's best efforts: The Spider's Web, The Great Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok, Batman, The Secret Code, and The Phantom maintained Columbia's own high standard. However, Columbia's serials often have a reputation for cheapness, because the studio usually subcontracted its serial production to outside producers: the Weiss Brothers (1937–1938), Larry Darmour (1939–1942), and finally Sam Katzman (1945–1956). Columbia built many serials around name-brand heroes. From newspaper comics, they got Terry and the Pirates, Mandrake the Magician, The Phantom, and Brenda Starr, Reporter; from the comic books, Blackhawk, Congo Bill, time traveler Brick Bradford, and Batman and Superman (although this last owed more to its radio incarnation, which the credits acknowledged); from radio, Jack Armstrong and Hop Harrigan; from the hero pulp characters like The Spider (two serials: The Spider's Web and The Spider Returns) and The Shadow (despite also being a popular radio series); from the British novelist Edgar Wallace, the first archer-superhero, The Green Archer; and even from television: Captain Video.

Columbia's early serials were very well received by audiences—exhibitors voted The Spider's Web (1938) the number-one serial of the year.[5] Former silent-serial director James W. Horne co-directed The Spider's Web, and his work secured him a permanent position in Columbia's serial unit. Horne had been a comedy specialist in the 1930s, often working with Laurel and Hardy, and most of his Columbia serials after 1939 are played tongue-in-cheek, with exaggerated villainy and improbable heroics (the hero takes on six men in a fistfight and wins). After Horne's death in 1942, the studio's serial output was somewhat more sober, but still aimed primarily at the juvenile audience. Batman (1943) was quite popular, and Superman (1948) was phenomenally successful despite using cartoon animation for the flying sequences instead of more expensive special effects.

Spencer Gordon Bennet, veteran director of silent serials, left Republic for Columbia in 1947. He directed or co-directed the studio's later serials. In 1954 producer Sam Katzman, whose budgets were already low, reduced them even more on serials. The last four Columbia serials were very-low-budget affairs, consisting mostly of action scenes and cliffhanger endings from older productions, and even employing the same actors for new scenes tying the old footage together. The new footage was so threadbare that it would often show the new hero watching the action from a distance, rather than actually participating in it. Columbia outlasted the other serial producers, its last being Blazing the Overland Trail (1956).

Availability

In theaters

There was always a market for action subjects in theaters, so as far back as 1935 independent film companies reissued older serials for new audiences. Universal brought back its Flash Gordon serials, and reissue distributors Film Classics and Realart re-released other Universal serials in the late 1940s. Both Republic and Columbia began re-releasing their older serials in 1947 as a cost-cutting measure: instead of making four new serials annually, the studios could now make three, and the fourth would be a reprint of an old serial.

Although Republic discontinued new serial production in 1955, the studio continued making older ones available to theaters through 1959. Columbia, which canceled new serials in 1956, kept older ones in circulation until 1966. Columbia still offers a handful of serials to today's theaters.

On television

Serials, with their short running times and episodic format, were very attractive to programmers in the early days of television. Veteran producers Louis Weiss and Nat Levine were among the first to offer their serials for broadcast.

The traditional week-to-week format of viewing serials was soon abandoned. As Republic executive David Bloom explained, "Attempts to program serials with full week intervals between chapters during the earlier days of television just about killed them off as effective sales product. It is understandable that this practice was adopted in view of their success in theaters on a Saturday matinee exhibition policy. But cliffhangers simply cannot be treated on TV as they were in theaters and still maintain the suspense so vital to their entertainment content. This suspense factor is diluted by the vast amount of other TV entertainment beamed between weekly showings."[6] TV stations began showing serials daily, generally on weekday afternoons, as children's programming.

In July 1956 TV distributor Serials Inc., a subsidiary of Jerry Hyams's Hygo Television Films, bought the 1936-1946 Universal serials (including all titles, rights, and interests) for $1,500,000.[7] Also in 1956, Columbia's TV subsidiary Screen Gems reprinted many of its serials for broadcast syndication. Only the films' endings were changed: Screen Gems replaced the "at this theater next week" title card with its standard Screen Gems logo. Screen Gems acquired the Hygo company in December 1956,[8] and packaged both Columbia and Universal serials for broadcast.[9] Republic's TV division, Hollywood Television Service, issued serials for television in their unedited theatrical form, as well as in specially edited six-chapter, half-hour editions ready made for TV time slots.

In the late 1970s and 1980s, serials were often revived on BBC television in the United Kingdom.[10]

Home movies

Both Republic and Columbia issued "highlights" versions of serials for the home-movie market. These were printed on 8mm silent film (and later Super 8 film) and sold directly to owners of home-movie projectors. Columbia was first to market, with three abbreviated chapters from its 1938 serial The Great Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok. When Batman became a national craze in 1965, Columbia issued a six-chapter silent version of its 1943 Batman. Republic followed suit with condensed silent versions of its own serials, including Adventures of Captain Marvel, G-Men vs. the Black Dragon, and Panther Girl of the Kongo.

With the rise in popularity of Super 8 sound-film equipment in the late 1970s, Columbia issued home-movie prints of entire 15-chapter serials, including Batman and Robin, Congo Bill, and Hop Harrigan. These were in print only briefly, until the studios turned away from home-movie films in favor of home video.

Home video

Film serials released to the home video market from original masters include most Republic titles (with a few exceptions, such as Ghost of Zorro)—which were released by Republic Pictures Home Video on VHS and sometimes laserdisc (sometimes under their re-release titles) mostly from transfers made from the original negatives, The Shadow, and Blackhawk, both released by Sony only on VHS, and DVD versions of Flash Gordon, Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars, and Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (Hearst), Adventures of Captain Marvel (Republic Pictures), Batman and Batman and Robin (Sony), Superman and Atom Man vs. Superman (Warner).

The Universal serials had been controlled by Serials Inc. until it closed in 1970. The company now known as VCI Entertainment obtained the rights. VCI is offering new Blu-Ray and DVD restorations of many Universal serials, including Gang Busters, Jungle Queen, Pirate Treasure, and three Buck Jones adventures. All of the new VCI releases derive from Universal's 35mm vault elements.

Notable restorations of partially lost or forgotten serials such as The Adventures of Tarzan, Beatrice Fairfax, The Lone Ranger Rides Again, Daredevils of the West, and King of the Mounties have been made available to fans by The Serial Squadron, a home-video concern specializing in action fare.

A gray market for serials also exists. These are unlicensed DVD releases of studio product, deriving from privately owned 16mm prints or even copies of previously released VHS or laserdisc editions. They are sold by various websites and Internet auctions. These DVDs vary between good and poor quality, depending on their source.

Major video companies have made a few serials available in new, restored editions from original prints and negatives. In 2017, Adventures of Captain Marvel became the first serial to be released on Blu-ray.

Amateur/fan efforts

An early attempt at a low-budget Western serial, filmed in color, was entitled The Silver Avenger. One or two chapters exist of this effort on 16mm film but it is not known whether the serial was ever completed.

The best-known fan-made chapter play is the four-chapter, silent 16mm Captain Celluloid vs. the Film Pirates, made to resemble Republic and Columbia serials of the 1940s and completed in 1966. The plot involved a masked villain named The Master Duper, one of three members of a Film Commission who attempts to steal the only known prints of priceless antique films, and the heroic Captain Celluloid, who wears a costume reminiscent of that of the Black Commando in the Columbia serial The Secret Code and is determined to uncover him. Roles in the serial are played by, among others, film historians and serial fans Alan G. Barbour, Al Kilgore, and William K. Everson.

In the 1980s, serial fan Blackie Seymour shot a complete 15-chapter serial called The Return of the Copperhead.[11] Seymour's only daughter, who operated the camera at the age of 8, attests that as of 2008 the serial was indeed filmed but the raw footage remains in cans, unedited.

In 2001, King of the Park Rangers, a one-chapter sound serial was released by Cliffhanger Productions on VHS video tape in sepia. It concerned the adventures of a Park Ranger named Patricia King and an FBI Agent who track down a trio of killers out to find buried treasure in the New Jersey Pine Barrens. A second ten-chapter serial, The Dangers of Deborah, in which a female reporter and a criminologist fight to uncover the identity of a mysterious villain named The Terror, was released by Cliffhanger Productions in 2008.

In 2006, Lamb4 Productions created its own homage to the film serials of the 1940s with its own serial titled "Wildcat." The story revolves around a super hero named Wildcat and his attempts to save the fictional Rite City from a masked villain known as the Roach. This eight-chapter serial was based heavily on popular super hero serials such as "Batman and Robin," "Captain America," and "The Adventures of Captain Marvel." After its premiere, "Wildcat" was posted on the official Lamb4 Productions YouTube channel for public viewing.[12]

Studio/commercial efforts, cartoons, and spoofery

The serial format was used with stories on the original run of The Mickey Mouse Club (1955–58), with each chapter running about six to ten minutes. The longer-running dramatic serials included "Corky and White Shadow", "The Adventures of Spin and Marty", "The Hardy Boys: The Mystery of the Applegate Treasure", "The Boys of the Western Sea", "The Secret of Mystery Lake", "The Hardy Boys: The Mystery of Ghost Farm", and The Adventures of Clint and Mac.

Other Disney programs shown on Walt Disney Presents in segments (such as The Scarecrow of Romney Marsh, The Swamp Fox, The Secret of Boyne Castle, The Mooncussers, and The Prince and the Pauper) and Disney feature films (including Treasure Island; The Three Lives of Thomasina; The Story of Robin Hood and His Merrie Men; Rob Roy, the Highland Rogue; and The Fighting Prince of Donegal) edited into segments for television presentation often had a cliffhanger-serial-like feel.

In England, in the 1950s and 60s, low-budget six-chapter serials such as Dusty Bates and Masters of Venus were released theatrically, but these were not particularly well-regarded or remembered.

The greatest number of serialized television programs to feature any single character were those made featuring "the Doctor", the BBC character introduced in 1963. Doctor Who serials would run anywhere from one to twelve episodes and were shown in weekly segments, as had been the original theatrical cliffhangers. Doctor Who was syndicated in the US as early as 1974, but did not gain a following in America until the mid-1980s when episodes featuring Tom Baker reached its shores. Although the series ended in 1989, it was revived in 2005, now following a more standard episode format.

The 1960s cartoon show Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle included two serial-style episodes per program. These spoofed the cliffhanger serial form, with pun-filled teasers for the next episode: "Be with us next time for Cheerful Little Pierful or Bomb Voyage". Within the Rocky and Bullwinkle show, the recurring but non-serialized Dudley Do-Right, specifically parodied the damsel in distress (Nell Fenwick) being tied to railroad tracks by arch villain Snidely Whiplash and rescued by the noble but clueless Dudley. The Hanna–Barbera Perils of Penelope Pitstop (spun off from the Hanna-Barbera hit Wacky Races) was a takeoff on the silent serials The Perils of Pauline and The Iron Claw, which featured Paul Lynde as the voice of the villain Sylvester Sneakley, alias "The Hooded Claw".

Danger Island, a multi-part story in under-10-minute episodes, was shown on the Saturday-morning Banana Splits program in the late 1960s. Episodes were short, full of wild action, and usually ended on a cliffhanger. This serial was directed by Richard Donner and featured the first African American action hero in a chapter play. The violence present in most of the episodes, though much of it was deliberately comical and would not be considered shocking today, also raised concerns at a time when violence in children's TV was at issue.

On February 27, 1979, NBC broadcast the first episode of an hour-long weekly television series Cliffhangers!, which had three segments, each with a different serial: a horror story (The Curse of Dracula, starring Michael Nouri), a science fiction/western (The Secret Empire, (inspired by 1935's The Phantom Empire) starring Geoffrey Scott as Marshal Jim Donner and Mark Lenard as Emperor Thorval) and a mystery (Stop Susan Williams!, starring Susan Anton, Ray Walston as Bob Richards, and Albert Paulsen as the villain Anthony Korf). Though final episodes were shot, the series was canceled and the last program aired on May 1, 1979 before all of the serials could conclude; only The Curse of Dracula was resolved.

In 2006, Dark Horse Indie films, through Image Entertainment, released a 6-chapter serial parody called Monarch of the Moon, detailing the adventures of a hero named the Yellow Jacket, who could control Yellow Jackets with his voice, battled "Japbots", and traveled to the moon. The end credits promised a second serial, Commie Commandos From Mars. Dark Horse attempted to promote the release as a just-found, never-before-released serial made in 1946, but suppressed by the US Government.

Public domain

Several serials are now in the public domain. These can often be downloaded legally over the internet or purchased as budget-priced DVDs. The list of public domain serials includes:

- The Vanishing Legion with Harry Carey (1931)

- The Hurricane Express with John Wayne (1933)

- Burn 'Em Up Barnes with Frankie Darro (1934)

- The Lost City with Kane Richmond (1935)

- The New Adventures of Tarzan with Herman Brix (1935)

- The Phantom Empire with Gene Autry (1935)

- Undersea Kingdom with Ray Corrigan (1936)

- Ace Drummond with John 'Dusty' King (1936)

- Dick Tracy with Ralph Byrd (1937)

- Zorro's Fighting Legion with Reed Hadley (1939)

- The Phantom Creeps with Bela Lugosi (1939)

- Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe with Buster Crabbe (1940)

- The Green Archer with Victor Jory (1940)

- Holt of the Secret Service with Jack Holt (1941)

- Gang Busters with Kent Taylor (1942)

- Captain America with Dick Purcell (1944)

- The Great Alaskan Mystery with Milburn Stone (1944)

- Zorro's Black Whip with Linda Stirling (1944)

- Radar Men from the Moon with Roy Barcroft (1952, originally conceived as a TV series)

Selected film serials

Selected serials of the Silent Era

- What Happened to Mary? (1912)

- The Adventures of Kathlyn (1913)

- Fantômas (1913) – (Cinema of France)

- The Perils of Pauline (1914)

- The Hazards of Helen (1917)

- The Exploits of Elaine (1914)

- Les Vampires (1915) – (Cinema of France)

- The Ventures of Marguerite (1915)

- Les Mystères de New York (1916)

- Le Masque aux Dents Blanches (1917)

- Judex (1917)

- Casey of the Coast Guard (1926)

- Tarzan the Mighty (1928)[13]

- Queen of the Northwoods (1929) (Last serial from Pathé)

- Tarzan the Tiger (1929) (partial sound)

Serials of the golden age of serials

The "golden age" of serials is generally from 1936 to 1945.[14] Postwar expenses limited large-scale production, so the serial form continued on a smaller scale for another decade.

- Ace Drummond (Universal, 1936)

- Custer's Last Stand (Weiss Bros., 1936)

- Darkest Africa (Republic, 1936)

- Flash Gordon (Universal, 1936)

- Robinson Crusoe of Clipper Island (Republic, 1936)

- Shadow of Chinatown (Victory, 1936)

- The Adventures of Frank Merriwell (Universal, 1936)

- The Clutching Hand (Weiss Bros., 1936)

- The Black Coin (Weiss Bros., 1936)

- The Phantom Rider (Universal, 1936)

- The Vigilantes Are Coming (Republic, 1936)

- Undersea Kingdom (Republic, 1936)

- Blake of Scotland Yard (Victory, 1937)

- Dick Tracy (Republic, 1937)

- Jungle Jim (Universal, 1937)

- Jungle Menace (Weiss Bros./Columbia, 1937)

- Radio Patrol (Universal, 1937)

- S.O.S. Coast Guard (Victory. 1937)

- Secret Agent X-9 (Universal, 1937)

- The Mysterious Pilot (Weiss Bros./Columbia, 1937)

- The Painted Stallion (Republic, 1937)

- Tim Tyler's Luck (Universal, 1937)

- Wild West Days (Universal, 1937)

- Zorro Rides Again (Republic, 1937)

- Dick Tracy Returns (Republic, 1938)

- Flaming Frontiers (Universal, 1938)

- Flash Gordon's Trip to Mars (Universal, 1938)

- Hawk of the Wilderness (Republic, 1938)

- Red Barry (Universal, 1938)

- The Fighting Devil Dogs (Republic, 1938)

- The Secret of Treasure Island (Weiss Bros./Columbia, 1938)

- The Great Adventures of Wild Bill Hickok (Columbia, 1938)

- The Lone Ranger (Republic, 1938)

- The Spider's Web (Columbia, 1938)

- Buck Rogers (Universal, 1939)

- Daredevils of the Red Circle (Republic, 1939)

- Dick Tracy's G-Men (Republic, 1939)

- Flying G-Men (Columbia, 1939)

- Mandrake the Magician (Columbia, 1939)

- Overland with Kit Carson (Columbia, 1939)

- Scouts to the Rescue (Universal, 1939)

- The Lone Ranger Rides Again (Republic, 1939)

- The Oregon Trail (Universal, 1939)

- The Phantom Creeps (Universal, 1939)

- Zorro's Fighting Legion (Republic, 1939)

- Adventures of Red Ryder (Republic, 1940)

- Deadwood Dick (Columbia, 1940)

- Drums of Fu Manchu (Republic, 1940)

- Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe (Universal, 1940)

- Junior G-Men (Universal, 1940)

- King of the Royal Mounted (Republic, 1940)

- Mysterious Doctor Satan (Republic, 1940)

- Terry and the Pirates (Columbia, 1940)

- The Green Archer (Columbia, 1940)

- The Green Hornet (Universal, 1940)

- The Green Hornet Strikes Again (Universal, 1940)

- The Shadow (Columbia, 1940)

- Winners of the West (Universal, 1940)

- Adventures of Captain Marvel (Republic, 1941)

- Dick Tracy vs. Crime, Inc. (Republic, 1941)

- Holt of the Secret Service (Columbia, 1941)

- Jungle Girl (Republic, 1941)

- King of the Texas Rangers (Republic, 1941)

- Riders of Death Valley (Universal, 1941)

- Sea Raiders (Universal, 1941)

- Sky Raiders (Universal, 1941)

- The Iron Claw (Columbia, 1941)

- The Spider Returns (Columbia, 1941)

- White Eagle (Columbia, 1941)

- Captain Midnight (Columbia, 1942)

- Don Winslow of the Navy (Universal, 1942)

- Gang Busters (Universal, 1942)

- Junior G-Men of the Air (Universal, 1942)

- King of the Mounties (Republic, 1942)

- Overland Mail (Universal, 1942)

- Perils of Nyoka (Republic, 1942)

- Perils of the Royal Mounted (Columbia, 1942)

- Spy Smasher (Republic, 1942)

- The Secret Code (Columbia, 1942)

- The Valley of Vanishing Men (Columbia, 1942)

- Adventures of the Flying Cadets (Universal, 1943)

- Batman (Columbia, 1943)

- Daredevils of the West (Republic, 1943)

- Don Winslow of the Coast Guard (Universal, 1943)

- G-Men vs. the Black Dragon (Republic, 1943)

- Secret Service in Darkest Africa (Republic, 1943)

- The Adventures of Smilin' Jack (Universal, 1943)

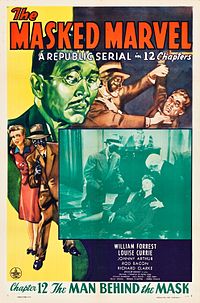

- The Masked Marvel (Republic, 1943)

- The Phantom (Columbia, 1943)

- Black Arrow (Columbia, 1944)

- Captain America (Republic, 1944)

- Haunted Harbor (Republic, 1944)

- Raiders of Ghost City (Universal, 1944)

- The Desert Hawk (Columbia, 1944)

- The Great Alaskan Mystery (Universal, 1944)

- Mystery of the River Boat (Universal, 1944)

- The Tiger Woman (Republic, 1944)

- Zorro's Black Whip (Republic, 1944)

- Brenda Starr, Reporter (Columbia, 1945)

- Federal Operator 99 (Republic, 1945)

- Jungle Queen (Universal, 1945)

- Jungle Raiders (Columbia, 1945)

- Manhunt of Mystery Island (Republic, 1945)

- Secret Agent X-9 (Universal, 1945)

- The Master Key (Universal, 1945)

- The Monster and the Ape (Columbia, 1945)

- The Purple Monster Strikes (Republic, 1945)

- The Royal Mounted Rides Again (Universal, 1945)

Other notable serials

- The King of the Kongo (1929) – First serial with sound (a Mascot production)

- The Mysterious Mr. M (1946) – Last serial from Universal

- Superman (1948) - First live-action appearance of Superman on film

- King of the Carnival (1955) – Last serial from Republic

- Blazing the Overland Trail (1956) – Last American serial (a Columbia production)

- Super Giant (1957) – Japanese tokusatsu superhero film serial (a Shintoho production), released in the U.S. as Starman

See also

- List of film serials by year

- List of film serials by studio

- Pulp magazines, a contemporary, and similar, form of serialized fiction.

- The Star Wars and Indiana Jones film series; creator George Lucas says that both series were based on and influenced by serial films.

- List of fictional shared universes in film and television

- Marvel Cinematic Universe

- Serial (radio and television)

References

- ^ "Progressive Silent Film List: Arsene Lupin Contra Sherlock Holmes". Silent Era. September 28, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ "Progressive Silent Film List: Raffles". Silent Era. October 12, 2004. Retrieved July 7, 2019.

- ^ Hollywood Reporter, "Columbia Drops Weiss Options for Serial Pix", Apr. 6, 1938.

- ^ Scott MacGillivray and Jan MacGillivray, Gloria Jean: A Little Bit of Heaven, iUniverse, 2005, p. 203.

- ^ Film Daily, Jan. 2, 1940, p. 2.

- ^ Broadcasting, April 15, 1963, pp. 74-75.

- ^ Motion Picture Herald, July 14, 1956, p. 17.

- ^ Motion Picture Daily, Dec. 7, 1956, p. 1.

- ^ Variety, July 10, 1957, p. 33.

- ^ "Search Results – BBC Genome". BBC.

- ^ "Blackie Seymour,, 72". Telegram & Gazette. May 4, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ "Wildcat" Movie Serial Official Site

- ^ "Progressive Silent Film List: Tarzan the Mighty". silentera.com. Retrieved February 21, 2008.

- ^ Images – Golden Age of the Serial. Retrieved July 10, 2007

Further reading

- Robert K. Klepper, Silent Films, 1877–1996, A Critical Guide to 646 Movies, McFarland & Company, ISBN 0-7864-2164-9

- Lahue, Kalton C. Bound and Gagged: The Story of the Silent Serials. New York: Castle Books 1968.

- Lahue, Kalton C. Continued Next Week : A History of the Moving Picture Serial. Norman. University of Oklahoma Press. 1969

External links

- Serial Squadron

- Silent Era, Index of Silent Era Serials

- In The Balcony

- Dieselpunk Industries

- Mickey Mouse Club serials

- TV Cream