Zillertal

The Ziller Valley[1][2][3] (German: Zillertal) is a valley in Tyrol, Austria that is drained by the Ziller River. It is the widest valley south of the Inn Valley (German: Inntal) and lends its name to the Zillertal Alps, the strongly glaciated section of the Alps in which it lies.[4] The Tux Alps lie to its west, while the lower grass peaks of the Kitzbühel Alps are found to the east.

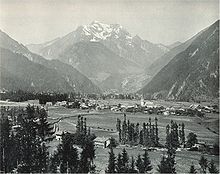

The Ziller Valley is one of the valley areas in Tyrol most visited by tourists.[4] Its largest settlement is Mayrhofen.

Geography

The Ziller Valley branches from the Inn trench near Jenbach, about 40 km northeast of Innsbruck, running mostly in a north–south direction. The Ziller Valley proper stretches from the village of Strass to Mayrhofen, where it separates into four smaller valleys, the Tux valley and the sparsely settled, so-called Gründe – Zamsergrund, Zillergrund and Stilluppgrund. Along the way, two more Gründe and the Gerlos valley, which leads to the Gerlos Pass and into Salzburg, branch off.

Unlike other side valleys of the Inntal, the Ziller Valley rises constantly, but only marginally, from one end to the other – only about 100 m over 30 km. Permanent settlements cover about 9% of the entire area of the Ziller Valley municipalities.

History

Near the Tuxer Joch, a pass between the Wipptal and the Tux valley, there have been archeological finds from middle Stone Age. The oldest remains of settlements in the Ziller Valley date back to the Illyrians during the late Bronze and early Iron Ages – a tribe from the Balkan Peninsula who were absorbed in that area by the Bavarians (Baiuvarii).

The earliest written record of the Ziller Valley dates from 889, when Arnulf of Carinthia granted land to the Archbishop of Salzburg in the "Cilarestale".[5] Ownership of the valley was divided along the Ziller River. Even today this division is visible, as churches on the right bank of the river generally have green towers and belong to Salzburg Diocese, while churches on the left bank have red towers and belong to Innsbruck Diocese.

In 1248, the land west of the Ziller was acquired by the Counts of Tyrol, while the lands east of the Ziller pledged as security to the Counts of Tyrol by the Lords of Rattenberg from 1290 to 1380. In 1504, with both the County of Tyrol and the Archbishopric of Salzburg dominated by the Habsburgs, the Ziller Valley was united under Emperor Maximilian and put under joint Tyrolean/Salzburgian rule.

In 1805, the Treaty of Pressburg ended the War of the Third Coalition and forced Austria to cede Tyrol to Bavaria. For the purposes of this treaty, the Ziller Valley was considered part of Salzburg and thus remained with Austria. The people of the Ziller Valley nevertheless joined Andreas Hofer's Tyrolean Rebellion of 1809 in the Battle of the Ziller Bridge (14 May). Later that year, the insurrection was defeated and the Ziller Valley briefly became Bavarian until the Congress of Vienna in 1814/1815.

While the relatively lenient stance of the archbishops of Salzburg had allowed the creation of small pockets of Protestantism in their lands since the Protestant Reformation, the remaining Protestants were oppressed more harshly during the Habsburg rule of the 19th century. In 1837, 437 Protestant inhabitants of the Ziller Valley left the valley after they were given the choice of renouncing the Augsburg Confession or emigrating to Silesia, where Frederick William III of Prussia offered them lands and housing near Erdmannsdorf (now Mysłakowice in western Poland).

In 1902, the Ziller Valley Railway was constructed, which still runs between Jenbach and Mayrhofen to this day, opening up the valley, the economy of which had previously relied mostly on agriculture and mining, to commerce and tourism. From 1921 to 1976, magnesium carbonate (and later tungsten) were mined around the Alpine pastures of the Schrofen and Wangl Almen above the Tuxertal A ropeway conveyor of more than 9 km length was used to transport the ore to the Ziller Valley Railway goods station in the valley below.

The Ziller Valley was known for its itinerant tradesmen, "farm doctors" and singing families. In the second half of the 19th century refuge huts were erected and trails established as climbing became a mass sport. The development of the area for tourism began in 1953/1954 with the construction of the Gerlosstein ski region, today the Zillertal Arena, which was soon followed by other lifts and the opening of the Mayrhofner Penkenbahn in 1954. The use of water power took off in the 1970s.

Economy

In the second half of the 20th century, after the end of mining in the valley, tourism became the area's dominant economic activity. In 2003, tourists stayed a total of 6 million nights in the valley, mostly during winter sports holidays. Following a phase of mergers by building connecting lifts during the 1990s and early 2000s, there are now four big ski areas, the largest of which is the Zillertal Arena, and three smaller satellite areas in the valley. Combined, they offer a total of more than 170 lifts and more than 630 km of downhill slopes.

Traditional agriculture – mostly cattle, dairy and some sheep farming on the Alm pastures – is still widespread and the large sawmill outside the village of Fügen is a sign of the lumber industry that also plays a significant role. The periphery of the area is home to a number of factories. Four large reservoirs in the Gründe supply water to a total of eight hydroelectric power stations, generating slightly more than 1,200 GWh per year.

Culture

The Ziller Valley is particularly renowned for its musical tradition. For instance, several families of travelling singers and organ builders from the valley have been credited with spreading the Christmas carol Silent Night across the world during the 19th and early 20th centuries. More recently, the Schürzenjäger band have had tremendous success in German-speaking countries with their crossover mix of Volksmusik and pop.

Religion

Catholic Church

The majority of the population belongs to the Catholic Church, which plays an important role in socio-cultural life.[6]

Protestantism

After the Reformation a lively Protestant movement developed in the Ziller Valley. There was animosity from the side of the Catholic Church, culminating in the forced exodus of Ziller Valley Protestants in 1837.[7] Today, some smaller Protestant congregations exist in Mayrhofen,[8] Jenbach[9] and Schwaz.

Gallery

- Berliner Hütte

- Neue Post in Mayrhofen

- Mainstreet in Mayrhofen

- Mainstreet in Mayrhofen

- Hintertux Glacier

- Pfitscherjochhaus and the Jochsee

See also

References

- ^ "Glacier Express and the Ziller Valley Steam Railway: Scenic Alpine Journeys". The Observer. February 15, 1998. p. 144. Retrieved December 26, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "A Song and Its Power". Santa Ynez Valley News. December 13, 2018. p. B1. Retrieved December 26, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tirol Has Lots of Charm". The Province. January 12, 2003. p. 72. Retrieved December 26, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Zillertal". Encyclopedia of Austria. Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ^ Martin Bitschnau; Hannes Obermair (2009), Tiroler Urkundenbuch. II. Abteilung: Die Urkunden zur Geschichte des Inn-, Eisack- und Pustertals. Band 1: Bis zum Jahr 1140 (in German), Universitätsverlag Wagner, pp. 80, no. 111, ISBN 978-3-7030-0469-8

- ^ Salzburg 2016 - Warum die Kirchtürme im Zillertal grün und rot sind. Tiroler Tageszeitung, 2015.

- ^ Der geschichtliche Ablauf der Auswanderung aus dem Zillertal. In: 1837-auswanderer.de. Zillertaler Auswanderer 1837. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ Free Evangelical Church in Mayrhofen

- ^ Evangelical Church Jenbach

External links

- Zillertal website (Summer)

- Zillertal website (Winter)

- Rock climbing and bouldering in Zillertal