Zhang Ji (revolutionary)

Zhang Ji | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

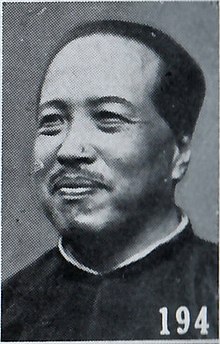

Zhang Ji as pictured in The Most Recent Biographies of Chinese Dignitaries | |||||||||

| Born | 31 August 1882 | ||||||||

| Died | 15 December 1947 (aged 65) Nanjing, China | ||||||||

| Nationality | Republic of China | ||||||||

| Occupation | Politician | ||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 張繼 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 张继 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||

| Chinese | 溥泉 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Zhang Ji (Chinese: 張繼; 31 August 1882 – 15 December 1947), also known by his courtesy name Pu Quan (溥泉), was a Chinese anarchist and revolutionary who became a leading member of the right-wing faction of the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist Party).

Zhang served as the first chairman of Fu Jen Catholic University from June 1929 to December 1947.[1]

Career

After a classical education in China, Zhang went to Japan in 1899, where he studied at Waseda University. In 1900, he joined other Chinese students in Tokyo to form the anti-Manchu Qingnianhui (Youth society), and became friends with other revolutionaries, Zhang Binglin and Zou Rong, and was attracted by Japanese radicals such as the journalist Shūsui Kōtoku. He was a contributor to Subao, the Shanghai journal which was a center of revolutionary activity and publication. When he went to Changsha, Hunan to teach, he also became a comrade of Huang Xing, another early revolutionary.[2] In 1904 he published an influential essay, "Anarchism and the Spirit of the Anarchists." Inspired by his readings on the French Revolution and the spirit of Danton, Zhang defended terrorism and assassination:

- Terrorists have declared openly: "the end justifies the means." What this means is that whatever the means may be, if helps achieve my goals, I may use it. If my means may bring security to the people of the nation, even if it entails killing, I may use it. The theory of the anarchists is similar to this; hence they advocate assassination."[3]

In 1905 Zhang was forced to return to Japan with a price on his head. There he joined Sun Yat-sen's organization, Tongmenghui (Revolutionary Society) and was made editor of its journal, Minbao (People's Journal). He ridiculed Sun's rival, Liang Qichao, calling him a "horse's fart." He and Liu Shipei were influenced by Japanese radicals and became the Tokyo counterpart to the Paris anarchists. [4]

Zhang spent the years from 1908-1911 in Paris, Geneva, and London. In Paris he was introduced to Li Shizeng and Wu Zhihui, heads of a group of anarchists. He spent the summer of 1908 in a rural anarchist commune in the north of France, the Colonie d'Aiglemont, where he milked cows and discussed anarchism with activists from many nations.[5] He returned to China when he heard news of the Revolution of 1911, and briefly was a member of Jiang Kanghu's Socialist Party of China, but soon rejoined Sun Yat-sen. However, Zhang and Sun had a brief falling out when Zhang opposed Sun's plan to reorganize his political party to demand personal loyalty to him. After several years of travel in Europe, the United States and Japan, Zhang became Sun's director of party affairs for North China in 1920.[2]

In the 1920s Zhang held high posts in the Kuomintang and opposed the influence of the Chinese Communist Party, which Sun had invited to become members of his party. After Sun's death in 1925, Zhang was elected to the State Council, and became associated with the group known as the Western Hills clique which convened in November 1925 to oppose communist influence. In the early 1930s Nationalist leaders several times sent Zhang to negotiate with fractious provincial forces. In a famous incident in 1935, Zhang and Hu Hanmin saved Wang Jingwei from assassination by leaping to shield him from a bomb. After the outbreak of war in 1937, Zhang concerned himself with gathering and editing materials for party history. In 1945 he continued to travel on party errands and in 1947 became director of the Guoshiguan (national history institute).[6]

Zhang died in Nanjing, at the age of 66, on 15 December 1947.[7]

References

Citations

- ^ 輔仁大學 校史室 >>輔仁歷史軌跡

- ^ a b Boorman (1967), p. 16.

- ^ Dirlik (1991), p. 65.

- ^ Zarrow (1990), p. 31, 45–47.

- ^ Zarrow (1990), p. 78.

- ^ Boorman (1967), p. 19-20.

- ^ Boorman (1967), p. 20.

Sources

- "Chang Chi," Boorman, Howard L., ed. (1967). Biographical Dictionary of Republican China Volume I. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231089589.

- Dirlik, Arif (1991). Anarchism in the Chinese Revolution. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520072979.

- Scalapino, Robert A. and George T. Yu (1961). The Chinese Anarchist Movement. Berkeley: Center for Chinese Studies, Institute of International Studies, University of California. At The Anarchist Library (Free Download). The online version is unpaginated.

- Zarrow, Peter Gue (1990). Anarchism and Chinese Political Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231071388.