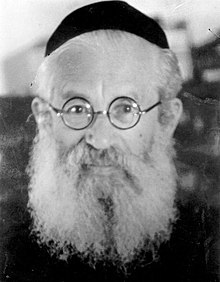

Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog

Rabbi Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of Israel |

| Personal life | |

| Born | 3 December 1888 |

| Died | 25 July 1959 (aged 70) |

| Nationality | Irish, Israeli |

| Religious life | |

| Religion | Judaism |

| Jewish leader | |

| Successor | Isser Yehuda Unterman (In Israel) |

Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog (Hebrew: יצחק הלוי הרצוג; 3 December 1888 – 25 July 1959), also known as Isaac Herzog or Hertzog,[2] was the first Chief Rabbi of Ireland, his term lasting from 1921 to 1936.[3] From 1936 until his death in 1959, he was Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of the British Mandate of Palestine and of Israel after its creation in 1948. He was the father of Chaim Herzog and grandfather of Isaac Herzog, both presidents of Israel.

Biography

Yitzhak Halevi Herzog was born at Łomża in Russian Poland, the son of Liba Miriam (Cyrowicz) and Joel Leib Herzog. He moved to the United Kingdom with his family in 1898, where they settled in Leeds. His initial schooling was largely at the instruction of his father who was a rabbi in Leeds and then later in Paris.[4]

After mastering Talmudic studies at a young age, Yitzhak went on to attend the Sorbonne and then later the University of London, where he received his doctorate. His thesis (where he coined the term Hebrew Porphyrology [5]), which made him famous in the Jewish world, concerned his claim of re-discovering Tekhelet, the type of blue dye once used for the making of Tzitzit.[6]

In 1935 he visited the land of Israel for the first time with strong desire to settle there.[7]

Later that same year, Rabbi Kook, the first Chief Rabbi of the Land of Israel died, and Rabbi Herzog was elected as the second Chief Rabbi of the Land of Israel and moved to reside in Jerusalem.[8]

In 1936, he testified in front of the Peel Commission in London and participated in 1939 in the "London Conference of 1939" between Jews and Arabs from Mandatory Palestine, convened by the British government.

During the Arab Revolt, he called, together with other rabbis, for adherence to the Havlagah policy of the Haganah and for avoidance of acts of revenge.[9]

He died on July 25, 1959, and was buried in the Sanhedria Cemetery in Jerusalem.[10]

Herzog's descendants have continued to be active in Israel's political life. His son Chaim Herzog was a general in the Israel Defense Forces and later became ambassador of Israel to the UN and sixth President of Israel. His son Yaakov Herzog served as Israel's ambassador to Canada and later as Director General of the Prime Minister's Office. He also accepted an offer to become Chief Rabbi of the British Commonwealth but due to ill health never took up that role.

His grandson Isaac Herzog is the President of Israel.[11] He also previously served as a member of the Knesset, Israel's parliament, and head of the opposition. He previously served as housing and tourism minister and minister of welfare[12] and later was chairman of the Jewish Agency.

Rabbinic career

Herzog served as rabbi of Belfast from 1916 to 1919 and was appointed rabbi of Dublin in 1919. A fluent Irish speaker[citation needed], he supported the First Dáil and the Irish republican cause during the Irish War of Independence, and became known as "the Sinn Féin Rabbi".[13] He went on to serve as Chief Rabbi of Ireland between 1922 and 1936, when he immigrated to Palestine to succeed rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook as Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi upon his death. He became a supporter of both the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Irgun.[14]

In May 1939, shortly before the Second World War, the British put out the White Paper of 1939 restricting Jewish immigration to Palestine. After leading a procession through the streets of Jerusalem, on the steps of the Hurva Synagogue he turned and said: "We cannot agree to the White Paper. Just as the prophets did before me, I hereby rip it in two." Some 40 years later, on 10 November 1975 Chaim Herzog repeated his father's gesture with the UN resolution that Zionism is equal to racism.[15]

Published works

Herzog was recognised as a great rabbinical authority, and he wrote many books and articles dealing with halachic problems surrounding the Torah and the State of Israel. Indeed, his writings helped shaped the attitude of the Religious Zionist Movement toward the State of Israel. Herzog authored:

- Main Institutions of Jewish Law

- Heichal Yitzchak

- Techukah leYisrael al pi haTorah

- Pesachim uKetavim

- The Royal Purple and the Biblical Blue

Awards and recognition

- In 1958, Herzog was awarded the Israel Prize, in rabbinical literature.[16]

See also

- History of the Jews in Ireland

- History of the Jews in Northern Ireland

- Herzog (disambiguation)

- Shmuel Wosner

- List of Israel Prize recipients

References

- ^ "All Israel Mourns Death of Chief Rabbi Herzog, Buried in Sanhedria" (PDF). Daily News Bulletin. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 27 July 1959. p. 1. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- ^ The spelling 'Hertzog' appears on his official letter of recommendation for Rev. Joseph Unterman, November 1938, in the signature as well as in the seal

- ^ "Herzog, Chaim (1918–1997)". Israel and Zionism. The Department for Jewish Zionist Education. Archived from the original on 26 September 2007. Retrieved 5 November 2007.

- ^ Herzog, Chaim (1996). Living History – A Memoir. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-679-43478-8.

- ^ "Hebrew Porphyrology". Ptil Tekhelet. 28 May 2023. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ Herzog, Chaim (1996). Living History – A Memoir. New York: Pantheon Books. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-679-43478-8.

- ^ "תולדות הרב יצחק אייזיק הלוי הרצוג / איתמר ורהפטיג - פרויקט בן־יהודה". benyehuda.org. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "תולדות הרב יצחק אייזיק הלוי הרצוג / איתמר ורהפטיג - פרויקט בן־יהודה". benyehuda.org. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "כרה הרבנים הראשיים — Davar – דבר 17 November 1937 — National Library of Israel │ Newspapers". www.nli.org.il. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "GRAVEZ". gravez.me. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Isaac Herzog elected Israel's 11th President". Globes. 6 February 2021. Retrieved 2 June 2021.

- ^ "Isaac Herzog". www.mfa.gov.il. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2023.

- ^ Benson, Asher (2007). Jewish Dublin. Dublin: A&A Farmer Ltd. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-906353-00-1.

- ^ Calder Walton, 'British Intelligence and Threats to British National Security After the Second World War,' in Matthew Grant (ed) The British Way in Cold Warfare: Intelligence, Diplomacy and the Bomb 1945-1975, A&C Black, 2011 pp.141-158 p.151.

- ^ Lammfromm, Arnon (2009). Chaim Herzog, HaNasi HaShishi (Chaim Herzog, the Sixth President) (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: Israel State Archives. p. 296. ISBN 978-965-279-037-8.

- ^ "Israel Prize recipients in 1958 (in Hebrew)". Israel Prize Official Site. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012.

External links

Media related to Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Yitzhak HaLevi Herzog at Wikiquote