Seuna (Yadava) dynasty

Seuna (Yadava) dynasty | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 1187[1]–1317 | |||||||||||

Flag of the Yadavas according to the Catalan Atlas Coinage of Yadavas of Devagiri, king Bhillama V (1185-1193). Central lotus blossom, two shri signs, elephant, conch, and “[Bhilla]/madeva” in Devanagari above arrow right | |||||||||||

Territory of the Yadavas and neighbouring polities, circa 1200-1300 CE.[2] | |||||||||||

| Capital | Devagiri | ||||||||||

| Common languages | Kannada Sanskrit Marathi | ||||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Earliest rulers | c. 860 | ||||||||||

• Established | c. 1187[1] | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 1317 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||||

The Seuna, Sevuna, or Yadavas of Devagiri (IAST: Seuṇa, c. 1187–1317)[3] was a medieval Indian dynasty, which at its peak ruled a realm stretching from the Narmada river in the north to the Tungabhadra river in the south, in the western part of the Deccan region. Its territory included present-day Maharashtra, northern Karnataka and parts of Madhya Pradesh, from its capital at Devagiri (present-day Daulatabad in modern Chhatrapati Sambhajinagar district, Maharashtra).

The Yadavas initially ruled as feudatories of the Western Chalukyas. Around the middle of the 12th century, as the Chalukya power waned, the Yadava king Bhillama V declared independence. The Yadavas reached their peak under Simhana II, and flourished until the early 14th century, when it was annexed by the Khalji dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate in 1308 CE.

Etymology

The Seuna dynasty claimed descent from the Yadavas and therefore, its kings are often referred to as the "Yadavas of Devagiri". The correct name of the dynasty, however, is Seuna or Sevuna.[4] The inscriptions of this dynasty, as well as those of contemporary kingdoms and empires, the Hoysalas, the Kakatiyas and the Western Chalukyas call them Seunas.[5] The name is probably derived from the name of their second ruler, "Seunachandra".

The "Sevuna" (or Seuna) name was brought back into use by John Faithfull Fleet in his 1894 book The dynasties of the Kanarese districts of the Bombay Presidency from the earliest historical times to the Musalman conquest of A.D. 1318.[6][7]

Origin

The earliest historical ruler of the Seuna/Yadava dynasty can be dated to the mid-9th century, but the origin of the dynasty is uncertain.[3] Little is known about their early history: their 13th century court poet Hemadri records the names of the family's early rulers, but his information about the pre-12th century rulers is often incomplete and inaccurate.[8]

The dynasty claimed descent from Yadu, a legendary hero mentioned in the Puranas.[8] According to this account, found in Hemadri's Vratakhanda as well as several inscriptions,[3] their ancestors originally resided at Mathura, and then migrated to Dvaraka (Dvaravati) in present-day Gujarat. A Jain legend states that the Jain saint Jinaprabhasuri saved the pregnant mother of the dynasty's founder Dridhaprahara from a great fire that destroyed Dvaraka. A family feudatory to the Yadavas migrated from Vallabhi (also in present-day Gujarat) to Khandesh. But otherwise, no historical evidence corroborates their connection to Dvaraka. The dynasty never tried to conquer Dvaraka, or establish any political or cultural connections with that region.[8] Its rulers started claiming to be descendants of Yadu and migrants from Dvaraka after becoming politically prominent.[9] Dvaraka was associated with Yadu's descendants, and the dynasty's claim of connection with that city may simply be a result of their claim of descent from Yadu rather than their actual geographic origin.[10] The Hoysalas, the southern neighbours of the dynasty, similarly claimed descent from Yadu and claimed to be the former lords of Dvaraka.[9] But there are no early records directly linking the Seuna Yadavas and Hoysala Yadavas to the Yadavas of North India.[11][12]

The territory of the early Yadava rulers was located in present-day Maharashtra,[9] and several scholars (especially Maharashtrian historians[13]) have claimed a "Maratha" origin for the dynasty.[14] However, Marathi, the language of present-day Maharashtra, began to appear as the dominant language in the dynasty's inscriptions only in the 14th century, before which Kannada and Sanskrit were the primary language of their inscriptions.[15][13] Marathi appears in around two hundred Yadava inscriptions, but usually as translation of or addition to Kannada and Sanskrit text. During the last half century of the dynasty's rule, it became the dominant language of epigraphy, which may have been a result of the Yadava attempts to connect with their Marathi-speaking subjects, and to distinguish themselves from the Kannada-speaking Hoysalas.[13] The earliest instance of the Yadavas using the term "marathe" as a self-designation appears in a 1311 inscription recording a donation to the Pandharpur temple,[16] towards the end of the dynasty's rule.[14] However the word was not used to indicate the Maratha caste but meant “belonging to Maharashtra”.[17]

Epigraphic evidence suggests that the dynasty likely emerged from a Kannada-speaking background.[18] Around five hundred Yadava inscriptions have been discovered, and Kannada is the most common language of these inscriptions, followed by Sanskrit.[13] Of the inscriptions found in present-day Karnataka (the oldest being from the reign of Bhillama II), most are in Kannada language and script; others are in the Kannada language but use Devanagari script.[5] Older inscriptions from Karnataka also attest to the existence of Yadava feudatories (such as Seunas of Masavadi) ruling in the Dharwad region in the 9th century, although these feudatories cannot be connected to the main line of the dynasty with certainty.[3][9] Many of the dynasty's rulers had Kannada names and titles such as "Dhadiyappa", "Bhillama", "Rajugi", "Vadugi" and "Vasugi", and "Kaliya Ballala". Some kings had names like "Simhana" (or "Singhana") and "Mallugi", which were also used by the Kalachuris of Kalyani, who ruled in present-day Karnataka. Records show that one of the early rulers, Seunachandra II, had a Kannada title, Sellavidega. The rulers had very close matrimonial relationships with Kannada-speaking royal families throughout their rule. Bhillama II was married to Lachchiyavve, who was from a Rashtrakuta descendant family in Karnataka. Vaddiga was married to Vaddiyavve, daughter of Rashtrakuta chieftain Dhorappa. Wives of Vesugi and Bhillama III were Chalukya princesess. The early Seuna coins also had Kannada legends engraved on them indicating it was a court language.[5] The early Yadavas may have migrated northwards owing to the political situation in the Deccan region,[19] or may have been dispatched by their Rashtrakuta overlords to rule the northern regions.[7]

Political history

As feudatories

The earliest historically attested ruler of the dynasty is Dridhaprahara (c. 860–880), who is said to have established the city of Chandradityapura (modern Chandor).[9][3] He probably rose to prominence by protecting the people of Khandesh region from enemy raiders, amid the instability brought by the Pratihara-Rashtrakuta war.[9]

Dridhaprahara's son and successor was Seunachandra (c. 880–900), after whom the dynasty was called Seuna-vamsha (IAST: Seuṇa-vaṃśa) and their territory was called Seuna-desha.[20][9] He probably became a Rashtrakuta feudatory after helping the Rashtrakutas against their northern neighbours, the Paramaras.[20] He established a new town called Seunapura (possibly modern Sinnar).[9]

Not much information is available about Seunachandra's successors — Dhadiyappa (or Dadhiyappa), Bhillama I, and Rajugi (or Rajiga) — who ruled during c. 900–950.[20][21] The next ruler Vandugi (also Vaddiga I or Baddiga) raised the family's political status by marrying into the imperial Rashtrakuta family. He married Vohivayya, a daughter of Dhorappa, who was a younger brother of the Rashtrakuta emperor Krishna III. Vandugi participated in Krishna's military campaigns, which may have resulted in an increase in his fief, although this cannot be said with certainty.[21]

Little is known about the next ruler, Dhadiyasa (c. 970–985).[21] His son Bhillama II acknowledged the suzerainty of the Kalyani Chalukya ruler Tailapa II, who overthrew the Rashtrakutas. As a Chalukya feudatory, he played an important role in Tailapa's victory over the Paramara king Munja.[20] Bhillama II was succeeded by Vesugi I (r. c. 1005–1025), who married Nayilladevi, the daughter of a Chalukya feudatory of Gujarat. The next ruler Bhillama III is known from his Kalas Budruk grant inscription.[22] He married Avalladevi, a daughter of the Chalukya king Jayasimha II, as attested by a Vasai (Bassein) inscription. He may have helped his father-in-law Jayasimha and his brother-in-law Someshvara I in their campaigns against the Paramara king Bhoja.[20][22]

For unknown reasons, the Yadava power seems to have declined over the next decade, during the reigns of Vesugi II (alias Vaddiga or Yadugi) and Bhillama IV. The next ruler was Seunachandra II, who, according to the Yadava records, restored the family's fortunes just like the god Hari had restored the earth's fortunes with his varaha incarnation. Seunachandra II appears to have ascended the throne around 1050, as he is attested by the 1052 Deolali inscription. He bore the feudatory title Maha-mandaleshvara and became the overlord of several sub-feudatories, including a family of Khandesh. A 1069 inscription indicates that he had a ministry of seven officers, all of whom bore high-sounding titles.[22] During his tenure, the Chalukya kingdom saw a war of succession between the brothers Someshvara II and Vikramaditya VI. Seunachandra II supported Vikramaditya (who ultimately succeeded), and rose to the position of Maha-mandaleshvara.[20] His son Airammadeva (or Erammadeva, r. c. 1085–1105), who helped him against Someshvara II, succeeded him. Airammadeva's queen was Yogalla, but little else is known about his reign.[23] The Asvi inscription credits him with helping place Vikramaditya on the Chalukya throne.[22]

Airammadeva was succeeded by his brother Simhana I (r. c. 1105–1120).[24] The Yadava records state that he helped his overlord Vikramaditya VI complete the Karpura-vrata ritual, by getting him a karpura elephant. An 1124 inscription mentions that he was ruling the Paliyanda-4000 province (identified as the area around modern Paranda).[23] The dynasty's history over the next fifty years is obscure. The 1142 Anjaneri inscription attests the rule of a person named Seunachandra, but Hemadri's records of the dynasty do not mention any Seunachandra III; historian R. G. Bhandarkar theorized that this Seunachandra may have been a Yadava sub-feudatory.[25]

The next known ruler Mallugi (r. c. 1145–1160) was a loyal feudatory to the Chalukya king Tailapa III. His general Dada and Dada's son Mahidhara fought with Tailapa's rebellious Kalachuri feudatory Bijjala II. He extended his territory by capturing Parnakheta (modern Patkhed in Akola district).[25] The Yadava records claim that he seized the elephants of the king of Utkala, but do not provide any details.[23] He also raided the kingdom of the Kakatiya ruler Rudra, but this campaign did not result in any territorial gains for him.[25] Mallugi was succeeded by his elder son Amara-gangeya, who was succeeded by his son Amara-mallugi (alias Mallugi II). The next ruler Kaliya-ballala, whose relationship to Mallugi is unknown, was probably an usurper. He was succeeded by Bhillama V around 1175.[25]

Rise as a sovereign power

At the time of Bhillama V's ascension in c. 1175, his nominal overlords — the Chalukyas — were busy fighting their former feudatories, such as the Hoysalas and the Kalachuris.[26] Bhillama raided the northern Gujarat Chaulukya and Paramara territories, although these invasions did not result in any territorial annexations. The Naddula Chahamana ruler Kelhana, who was a Gujarat Chaulukya feudatory, forced him to retreat.[27] Meanwhile, the Hoysala ruler Ballala II invaded the Chalukya capital Kalyani, forcing Bhillama's overlord Someshvara to flee.[1]

Around 1187, Bhillama forced Ballala to retreat, conquered the former Chalukya capital Kalyani, and declared himself a sovereign ruler.[1] He then established Devagiri, a formidable natural stronghold, which became the new Yadava capital.[28][29]

In the late 1180s, Ballala launched a campaign against Bhillama, and decisively defeated his army at Soratur.[30] The Yadavas were driven to the north of the Malaprabha and Krishna rivers, which formed the Yadava-Hoysala border for the next two decades.[30]

Imperial expansion

Bhillama's son Jaitugi successfully invaded the Kakatiya kingdom around 1194, and forced them to accept the Yadava suzerainty.[32][33]

Jaitugi's son Simhana, who succeeded him around either 1200[34] or 1210,[35] is regarded as the dynasty's greatest ruler.[34] At its height, his kingdom probably extended from the Narmada River in the north to the Tungabhadra River in the south, and from the Arabian Sea in the west to the western part of the present-day Telangana in the east.[36] He launched a military campaign against the Hoysalas (who were engaged in a war with the Pandyas), and captured a substantial part of their territory.[37][38] The Rattas of Saundatti, who formerly acknowledged the Hoysala suzerainty, became his feudatories, and helped him expand the Yadava power southwards.[38] In 1215, Simhana successfully invaded the northern Paramara kingdom. According to Hemadri, this invasion resulted in the death of the Paramara king Arjunavarman, although this claim is of doubtful veracity.[39] Around 1216, Simhana defeated the Kohalpur Shilahara king Bhoja II, a former feudatory, who had asserted his sovereignty. The Shilahara kingdom, including its capital Kolhapur, was annexed to the Yadava kingdom as a result of this victory.[40][38]

In 1220, Simhana sent an army to the Lata region in present-day Gujarat, whose rulers kept shifting his allegiance between the Yadavas, the Paramaras, and the Chaulukyas.[41] Simhana's general Kholeshvara killed the defending ruler Simha, and captured Lata.[42] Simhana then appointed Simha's son Shankha as a Yadava vassal in Lata.[43] Sometime later, the Chaulukya general Lavanaprasada invaded Lata, and captured the important port city of Khambhat. Simhana's feudatory Shankha invaded Chaulukya-controlled territory twice, with his help, but was forced to retreat.[44] The Chaulukya-Yadava conflict came to end in c. 1232 with a peace treaty.[45] In the 1240s, Lavanaprasada's grandson Visaladeva usurped the power in Gujarat, and became the first Vagehla monarch. During his reign, Simhana's forces invaded Gujarat unsuccessfully, and the Yadava general Rama (a son of Kholeshvara) was killed in a battle.[46]

Several Yadava feudatories kept shifting their allegiance between the Yadavas and the Hoysalas, and tried to assert their independence whenever presented with an opportunity. Simhana's general Bichana subdued several such chiefs, including the Rattas, the Guttas of Dharwad, the Kadambas of Hangal, and the Kadambas of Goa.[47] The Kakatiya king Ganapati served him as a feudatory for several years, but assumed independence towards the end of his reign. However, Ganapati did not adopt an aggressive attitude towards the Yadavas, so no major conflict happened between the two dynasties during Simhana's reign.[48]

Simhana was succeeded by his grandson Krishna (alias Kannara), who invaded the Paramara kingdom, which had weakened because of invasions from the Delhi Sultanate. He defeated the Paramara king sometime before 1250, although this victory did not result in any territorial annexation.[49] Krishna also attempted an invasion of the Vaghela-ruled Gujarat, but this conflict was inconclusive, with both sides claiming victory.[49][50] He also fought against the Hoysalas; again, both sides claim victory in this conflict.[50]

Krishna's younger brother and successor Mahadeva curbed a rebellion by the Shilaharas of northern Konkan, whose ruler Someshvara had attempted to assert his sovereignty.[51] He invaded the eastern Kakatiya kingdom, taking advantage of rebellions against the Kakatiya queen Rudrama,[52] but this invasion appears to have been repulsed.[53] He also invaded the southern Hoysala kingdom, but this invasion was repulsed by the Hoysala king Narasimha II.[52] Mahadeva's Kadamba feudatories rebelled against him, but this rebellion was suppressed by his general Balige-deva around 1268.[52]

Mahadeva was succeeded by his son Ammana, who was dethroned by Krishna's son Ramachandra after a short reign in 1270.[54][55] During the first half of his reign, Ramachandra adopted an aggressive policy against his neighbours. In the 1270s, he invaded the northern Paramara kingdom, which had been weakened by internal strife, and easily defeated the Paramara army.[56] The Yadava army was also involved in skirmishes against their north-western neighbours, the Vaghelas, with both sides claiming victory.[56][57] In 1275, he sent a powerful army led by Tikkama to the southern Hoysala kingdom. Tikkama gathered a large plunder from this invasion, although ultimately, his army was forced to retreat in 1276.[58] Ramachandra lost some of his territories, including Raichur, to the Kakatiyas.[57]

The Purushottamapuri inscription of Ramachandra suggests that he expanded the Yadava kingdom at its north-east frontier. First, he subjugated the rulers of Vajrakara (probably modern Vairagarh) and Bhandagara (modern Bhandara).[59] Next, he marched to the defunct Kalachuri kingdom, and occupied the former Kalachuri capital Tripuri (modern Tewar near Jabalpur). He also constructed a temple at Varanasi, which suggests that he may have occupied Varanasi for 2–3 years, amid the confusion caused by the Delhi Sultanate's invasion of the local Gahadavala kingdom.[59] He crushed a rebellion by the Yadava feudatories at Khed and Sangameshwar in Konkan.[59]

Decline

), while coastal cities are under the black flag of the Delhi Sultanate (

), while coastal cities are under the black flag of the Delhi Sultanate ( ).[60][61] Devagiri was ultimately captured by ‘Alā ud-Dīn Khaljī in 1307.[62] The trading ship raises the flag of the Ilkhanate (

).[60][61] Devagiri was ultimately captured by ‘Alā ud-Dīn Khaljī in 1307.[62] The trading ship raises the flag of the Ilkhanate ( ).

).Ramachandra seems to have faced invasions by Turko-Persian Islamic armies from northern India (called "mlechchhas" or "Turukas") since the 1270s, for a 1278 inscription calls him a "Great Boar in securing the earth from the oppression of the Turks". Historian P. M. Joshi dismisses this as a boastful claim, and theorizes that he may have "chastised some Muslim officials" in the coastal region between Goa and Chaul.[63] In 1296, Ala-ud-din Khalji of the Delhi Sultanate successfully raided Devagiri. Khalji restored it to Ramachandra in return for his promise of payment of a high ransom and an annual tribute.[64] However, this was not paid and the Seuna kingdom's arrears to Khalji kept mounting. In 1307, Khalji sent an army commanded by Malik Kafur, accompanied by Khwaja Haji, to Devagiri. The Muslim governors of Malwa and Gujarat were ordered to help Malik Kafur. Their huge army conquered the weakened and defeated forces of Devagiri almost without a battle. Ramachandra was taken to Delhi. Khalji reinstated Ramachandra as governor in return for a promise to help him subdue the Hindu kingdoms in southern India. In 1310, Malik Kafur mounted an assault on the Kakatiya kingdom from Devagiri.[4] The plundered wealth obtained from the Kakatiyas helped finance the freelance soldiers of the Khalji army.[65]

Ramachandra's successor Simhana III challenged the supremacy of Khalji, who sent Malik Kafur to recapture Devagiri in 1313. Simhana III was killed in the ensuing battle[66] and Khalji's army occupied Devagiri. The kingdom was annexed by the Khalji sultanate in 1317. Many years later, Muhammad Tughluq of the Tughluq dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate subsequently renamed the city Daulatabad.[67]

Rulers

The rulers of the Seuna / Yadava dynasty include:[68][69]

Feudatories

- Dridhaprahara, r. c. 860–880

- Seunachandra, r. c. 880–900

- Dhadiyappa I, r. c. 900-?

- Bhillama I, r. c. 925

- Rajugi, r. c. ?–950

- Vaddiga, r. c. 950–970

- Dhadiyasa, r. c. 970–985

- Bhillama II, r. c. 985–1005

- Vesugi I, r. c. 1005–1025

- Bhillama III, r. c. 1025–?

- Vesugi II alias Vaddiga or Yadugi, r. c. ?–1050

- Seunachandra II, r. c. 1050–1085

- Airammadeva or Erammadeva, r. c. 1085–1105

- Simhana I (also transliterated as Singhana I) alias Simharaja, r. c. 1105–1120

- Obscure rulers, r. c. 1120–1145

- Mallugi I, r. c. 1145–1160

- Amaragangeya

- Amara-mallugi alias Mallugi II

- Kaliya-ballala, r. c. ?–1175

- Bhillama V, r. c. 1175–1187

Sovereigns

- Bhillama V, r. c. 1187–1191

- Jaitugi I, r. c. 1191–1200 or 1191–1210

- Simhana II, r. c. 1200–1246 or 1210–1246

- Krishna alias Kannara, r. c. 1246–1261

- Mahadeva, r.c. 1261–1270

- Ammana, r. c. 1270

- Ramachandra alias Ramadeva, r. c. 1271–1308

as tributaries of the Khalji dynasty of the Delhi Sultanate

- Ramachandra, r. c. 1308–1311

- Simhana III alias Shankaradeva, r. c. 1311–1313

- Harapaladeva, r. c. 1313–1317

Literature

Marathi

The Yadavas were the first major dynasty to use Marathi as an official language.[70] Earlier, both Sanskrit and Kannada had been used for official inscriptions in present-day Maharashtra; subsequently, at least partly due to the efforts of the Yadava rulers, Marathi became the dominant official language of the region.[71] Even if they were not of Marathi origin, towards the end of their reign, they certainly identified with the Marathi language.[14] The early Marathi literature emerged during the Yadava rule, because of which some scholars have theorized that it was produced with support from the Yadava rulers.[72] However, there is no evidence that the Yadava royal court directly supported the production of Marathi literature with state funds, although it regarded Marathi as a significant language for connecting with the general public.[73]

Hemadri, a minister in the Yadava court, attempted to formalize Marathi with Sanskrit expressions to boost its status as a court language.[74] Saint-poet Dnyaneshwar wrote Dnyaneshwari (c. 1290), a Marathi-language commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, during Ramachandra's rule. He also composed devotional songs called abhangas. Dnyaneshwar gave a higher status to Marathi by translating the sacred Geeta from Sanskrit. Mukundaraja wrote the Marathi-language philosophical treatises Paramamrita and Vivekasindhu during the Yadava period.[75] The Mahanubhava religious sect, which became prominent in present-day Maharshtra during the late Yadava period, boosted the status of Marathi as a literary language.[75] Mahimabhatta wrote Lilacharita, a biography of the sect's founder Chakradhara. The text claims that Hemadri (who was a Brahmanist) was jealous of Chakradhara's popularity, and the Yadava king Ramachandra ordered killing of Chakradhara, who escaped with his yogic powers. The claim is of doubtful historicity.[7]

Kannada

Kannada was the court language of Yadavas till late Seuna times, as is evident from a number of Kannada-language inscriptions (see Origin section). Kamalabhava a Jain scholar, patronised by Bhillama V, wrote Santhishwara-purana. Achanna composed Vardhamana-purana in 1198. Amugideva, patronised by Simhana II, composed many Vachanas or devotional songs. Chaundarasa of Pandharapur wrote Dashakumara Charite around 1300.[76][77][78]

Sanskrit

Simhana was a great patron of learning and literature. He established the college of astronomy to study the work of celebrated astronomer Bhaskaracharya. The Sangita Ratnakara, an authoritative Sanskrit work on Indian music was written by Śārṅgadeva (or Shrangadeva) during Simhana's reign.[79]

Hemadri compiled the encyclopedic Sanskrit work Chaturvarga Chintamani. He is said to have built many temples in a style known after him – Hemadapanti.[80] He wrote many books on vaidhyakshastra (medical science) and he introduced and supported bajra cultivation.[81]

Other Sanskrit literary works created during the Seuna period include:

- Suktimuktavali by Jalhana

- Hammiramadhana by Jayasimha Suri[citation needed]

- Karnakutuhala and Siddhanta Shiromani by Bhaskaracharya

- Anantadeva's commentaries on Varahamihira's Brijajjataka and Brahmagupta's Brihatsputa siddhanta

- Haripaladeva's Sangeetasudhakara, a treatise on Indian Classical Music, which bifurcates Indian classical music as Hindustani Music and Carnatic Music for the first time, acknowledging the Muslim influence on Indian music.[82][failed verification]

Architecture

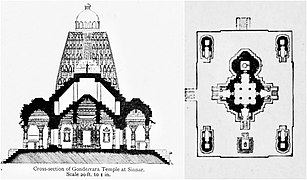

The Gondeshwar temple is an 11th-12th century Hindu temple located in Sinnar, a town in the Nashik district of Maharashtra, India. It features a panchayatana plan; with a main shrine dedicated to Shiva; and four subsidiary shrines dedicated to Surya, Vishnu, Parvati, and Ganesha. The Gondeshwar temple was built during the rule of the Seuna (Yadava) dynasty, and is variously dated to either the 11th[83] or the 12th century.[84]

- The temple in 1897

- In 2017, with the finial lost

- Cross section and plan

References

| History of South Asia |

|---|

|

- ^ a b c A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 524.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 147, map XIV.3 (c). ISBN 0226742210.

- ^ a b c d e T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 137.

- ^ a b Keay, John (1 May 2001). India: A History. Atlantic Monthly Pr. pp. 252–257. ISBN 0-8021-3797-0. The quoted pages can be read at Google Book Search.

- ^ a b c Suryanath Kamat 1980, pp. 136–137.

- ^ The Dynasties of the Kanarese Districts of the Bombay Presidency"(1894) J.F.Fleet, Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency (Vol-1, Part-II, Book-III) ISBN 81-206-0277-3

- ^ a b c A. V. Narasimha Murthy 1971, p. 32.

- ^ a b c A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 515.

- ^ a b c d e f g h A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 516.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, pp. 515–516.

- ^ Quotation:"There was not even a tradition to back such poetic fancy"(William Coelho in Kamath, 2001, p122). Quotation:"All royal families in South India in the 10th and 11th century deviced puranic genealogies" (Kamath 2001, p122)

- ^ Quotation:"It is therefore clear that there was a craze among the rulers of the south at this time (11th century) to connect their families with dynasties from the north" (Moraes 1931, p10–11)

- ^ a b c d Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, p. 53.

- ^ a b c Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, p. 316.

- ^ Colin P. Masica 1993, p. 45.

- ^ Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, p. 314.

- ^ Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, p. 315.

- ^ Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, pp. 51–54.

- ^ Shrinivas Ritti 1973.

- ^ a b c d e f T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 138.

- ^ a b c A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 517.

- ^ a b c d A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 518.

- ^ a b c T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 139.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 518-519.

- ^ a b c d A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 519.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 522.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 523.

- ^ T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 140.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (25 July 2019). "Chapter 2, first page". India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-196655-7.

- ^ a b A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 525.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (1978). A Historical atlas of South Asia. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 147, map XIV.3 (c). ISBN 0226742210.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 529.

- ^ T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 143.

- ^ a b T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 144.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 531.

- ^ T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 147.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 532.

- ^ a b c T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 145.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 534.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 533.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 535.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, pp. 535–536.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 536.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, pp. 536–537.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 537.

- ^ T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 146.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 538.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, pp. 538–539.

- ^ a b A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 544.

- ^ a b T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 148.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 546.

- ^ a b c A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 547.

- ^ T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 150.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, pp. 548–549.

- ^ T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 151.

- ^ a b A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 549.

- ^ a b T. V. Mahalingam 1957, p. 152.

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 550.

- ^ a b c A. S. Altekar 1960, p. 551.

- ^ Antiquities from San Thomé and Mylapore. 1936. pp. 264–265.

- ^ Kadoi, Yuka (2010). "On the Timurid flag". Beiträge zur islamischen Kunst und Archäologie. 2: 148.

...helps identify another curious flag found in northern India – a brown or originally silver flag with a vertical black line – as the flag of the Delhi Sultanate (602-962/1206-1555).

- ^ Beaujard, Philippe (2019). [978-1108424653 The worlds of the Indian Ocean : a global history : a revised and updated translation]. Cambridge University Press. p. Chapter 8. ISBN 978-1-108-42456-1.

The sultan captured the Rajput fort of Chitor, in Rājasthān, and in 1310 he subjected most of the Deccan to his power. He took Devagiri – the capital of the Yādava – in 1307

{{cite book}}: Check|url=value (help) - ^ P. M. Joshi 1966, p. 206.

- ^ Bennett, Mathew (2001). Dictionary of Ancient & Medieval Warfare. Stackpole Books. p. 98. ISBN 0-8117-2610-X.. The quoted pages can be read at Google Book Search.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (25 July 2019). "Chapter 2". India in the Persianate Age: 1000-1765. Penguin UK. ISBN 978-0-14-196655-7.

- ^ Michell, George (10 June 1999). Architecture and Art of the Deccan Sultanates. Arizona University Press. p. 5. ISBN 0-521-56321-6.

- ^ "Yādava Dynasty" Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica 2007 Ultimate Reference Suite

- ^ A. S. Altekar 1960, pp. 516–551.

- ^ T. V. Mahalingam 1957, pp. 137–152.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2001, p. 211.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2001, p. 212.

- ^ Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, p. 74,86.

- ^ Christian Lee Novetzke 2016, p. x,74.

- ^ Cynthia Talbot 2001, pp. 211–212.

- ^ a b Onkar Prasad Verma 1970, p. 266.

- ^ R. Narasimhacharya, p. 68, History of Kannada Literature, 1988, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, Madras, 1988 ISBN 81-206-0303-6

- ^ Suryanath Kamat 1980, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Sujit Mukherjee, p. 410, p. 247, "Dictionary of Indian Literature One: Beginnings - 1850", 1999, Orient Blackswan, Delhi, ISBN 81 250 1453 5

- ^ Gurinder Singh Mann (2001). The Making of Sikh Scripture. Oxford University Press US. p. 1. ISBN 0-19-513024-3.

- ^ Digambar Balkrishna Mokashi (1987). Palkhi: An Indian Pilgrimage. SUNY Press. p. 37. ISBN 0-88706-461-2.

- ^ Marathyancha Itihaas by Dr. S.G Kolarkar, p.4, Shri Mangesh Prakashan, Nagpur.

- ^ "ITCSRA FAQ on Indian Classical Music". Retrieved 11 December 2007.

- ^ Takeo Kamiya 2003, p. 382.

- ^ Cyril M. Harris 2013, p. 806.

Bibliography

- Cyril M. Harris (2013). Illustrated Dictionary of Historic Architecture. Courier. p. 806. ISBN 978-0-486-13211-2.

- A. S. Altekar (1960). Ghulam Yazdani (ed.). The Early History of the Deccan Parts. Vol. VIII: Yādavas of Seuṇadeśa. Oxford University Press. OCLC 59001459.

- A. V. Narasimha Murthy (1971). The Sevunas of Devagiri. Rao and Raghavan.

- Christian Lee Novetzke (2016). The Quotidian Revolution: Vernacularization, Religion, and the Premodern Public Sphere in India. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-54241-8.

- Cynthia Talbot (2001). Precolonial India in Practice: Society, Region, and Identity in Medieval Andhra. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-803123-9.

- Colin P. Masica (1993). "Subsequent spread of Indo-Aryan in the subcontinent and beyond". The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Onkar Prasad Verma (1970). The Yādavas and Their Times. Vidarbha Samshodhan Mandal. OCLC 138387.

- P. M. Joshi (1966). "Alauddin Khalji's first campaign against Devagiri". In H. K. Sherwani (ed.). Dr. Ghulam Yazdani Commemoration Volume. Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Oriental Research Institute. OCLC 226900.

- Shrinivas Ritti (1973). The Seunas: The Yadavas of Devagiri. Department of Ancient Indian History and Epigraphy, Karnatak University.

- Suryanath Kamat (1980). A Concise History of Karnataka. Archana Prakashana.

- T. V. Mahalingam (1957). "The Seunas of Devagiri". In R. S. Sharma (ed.). A Comprehensive history of India: A.D. 985-1206. Vol. 4 (Part 1). Indian History Congress / People's Publishing House. ISBN 978-81-7007-121-1.

- Takeo Kamiya (2003). "Sinnar: Gondeshwara temple". The Guide to the Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent. Translated by Annabel Lopez and Bevinda Collaco. Architecture Autonomous. ISBN 978-4-88706-141-5.