Classic of Filial Piety

Niu Shuyu's frontispiece of The Classic of Filial Piety (1826) | |

| Author | (trad.) Confucius |

|---|---|

| Published | c. 4th century BC |

| Classic of Filial Piety | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

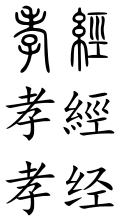

| Traditional Chinese | 孝經 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 孝经 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | filial piety classic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | Hiếu Kinh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 孝經 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 효경 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 孝經 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 孝経 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hiragana | こうきょう | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Classic of Filial Piety, also known by its Chinese name as the Xiaojing, is a Confucian classic treatise giving advice on filial piety: that is, how to behave towards a senior such as a father, an elder brother, or a ruler.

The text was most likely written during the late Warring States period and early Han dynasty and claims to be a conversation between Confucius and his student Zengzi. The text was widely used during the Han and later dynasties to teach young children basic moral messages as they learned to read.[2]

Authorship

The text dates from the 4th century BC to 3rd century BC.[3] It is not known who actually wrote the document. It is attributed to a conversation between Confucius and his disciple Zengzi. A 12th-century author named He Yin claimed: "The Classic of Filial Piety was not made by Zengzi himself. When he retired from his conversation (or conversations) with Kung-ne on the subject of Filial Piety, he repeated to the disciples of his own school what (the master) had said, and they classified the sayings, and formed the treatise."

Content

As the title suggests, the text elaborates on filial piety, which is a core Confucian value. The text argues that people who love and serve their parents will do the same for their rulers, leading to a harmonious society. For example,[4]

資於事父以事母,而愛同;資於事父以事君,而敬同。

As they serve their fathers, so they serve their mothers, and they love them equally. As they serve their fathers, so they serve their rulers, and they reverence them equally.

Influence

The Classic of Filial Piety occupied an important position in classical education as one of the most popular foundational texts through to late imperial China.[5] The text was used in elementary and moral education together with the Analects, Elementary Learning, and the Biographies of Exemplary Women.[6] Study of the text was also mentioned in epitaphs as an indication of a person's good character. It was a practice to read aloud the text when mourning one's parents. The text was also important politically, partly because filial piety was both a means of demonstrating moral virtue and entering officialdom for those with family connections to the imperial court.[7] The text was important in Neo-Confucianism and was quoted by the influential Song figure and Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi.

Translations

Many Japanese translations of the Xiaojing exist. The following are the primary Western language translations.

- Legge, James (1879). The Hsiâo King, in Sacred Books of the East, vol. III. Oxford University Press.

- (in French) de Rosny, Leon (1889). Le Hiao-king. Paris: Maisonneuve et Ch. Leclerc. Republished (1893) as Le morale de Confucius: le livre sacré de la piété filiale. Paris: J. Maisonneuve.

- Chen, Ivan (1908). The Book of Filial Duty. London: J. Murray; New York: E.P. Dutton & Co.

- (in German) Wilhelm, Richard (1940). Hiau Ging: das Buch der Ehrfurcht. Peking: Verlag der Pekinger Pappelinsel.

- Makra, Mary Lelia (1961). The Hsiao Ching, Sih, Paul K. T., ed. New York: St. John's University Press.

- Goldin, Paul R. (2005). "Filial Piety" in Hawaii Reader in Traditional Chinese Culture, Victor H. Mair et al., eds. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. 106-12.

- Rosemont, Henry, Jr.; Ames, Roger T. (2009). The Chinese Classic of Family Reverence: A Philosophical Translation of the Xiaojing. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

See also

- Family as a model for the state

- Role ethics

- Ma Rong (79-166) and the Classic of Loyalty.

References

Citations

- ^ Wiktionary: Appendix:Baxter-Sagart Old Chinese reconstruction

- ^ Ebrey, Patricia Buckley (1993). Chinese civilization : a sourcebook (2nd ed.). New York: The Free Press. pp. 64. ISBN 002908752X. OCLC 27226697.

- ^ "Li Gonglin. The Classic of Filial Piety". The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Classic of Filial Piety, composed between 350 and 200 B.C., teaches a simple but all-embracing lesson: beginning humbly at home, filial piety not only ensures success in a man's life but also brings peace and harmony to the world at large.

- ^ Legge, James. "The Classic of Filial Piety 《孝經》". Chinese Notes. Retrieved 2 May 2018.

- ^ Lu (2017), p. 268.

- ^ Lu (2017), p. 272.

- ^ Lu (2017), pp. 273–277.

Works cited

- Barnhart, Richard (1993). Li Kung-lin's Classic of Filial Piety. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870996797.

- Boltz, William (1993). "Hsiao ching 孝經". In Loewe, Michael (ed.). Early Chinese Texts: A Bibliographical Guide. Berkeley, CA: Society for the Study of Early China; Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California Berkeley. pp. 141–52. ISBN 1-55729-043-1.

- Chen, Ivan (1908). The Book of Filial Duty. London: John Murray.

- Lu, Miaw-Fen (2017). "The Reception of the Classic of Fillial Piety from Medieval to Late Imperial China". In Goldin, Paul R (ed.). A Concise Companion to Confucius. Oxford: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 268–285. ISBN 9781118783832.

- Rosemont, Henry Jr.; Roger T. Ames (2009). The Chinese Classic of Family Reverence: a Philosophical Translation of the Xiaojing. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0824833480.

External links

- Xiaojing

- Xiao Jing (Full text in Chinese with English translation)

- Xiao Jing (Full text in Chinese with Explanatory Commentary)

- The Classic of Filial Piety 《孝經》 (Full text in Chinese and English with matching vocabulary)