Wrangel Island

Wrangel Island in October 2018 | |

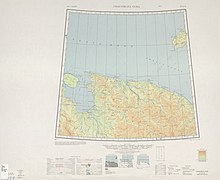

Location of Wrangel Island | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Near Chukchi Sea |

| Coordinates | 71°14′N 179°25′W / 71.233°N 179.417°W |

| Area | 7,600 km2 (2,900 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 1,096 m (3596 ft) |

| Highest point | Soviet Mountain |

| Administration | |

| Federal District | Far Eastern |

| Autonomous Okrug | Chukotka |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 0 |

| Official name | Natural System of Wrangel Island Reserve |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | ix, x |

| Designated | 2004 (28th session) |

| Reference no. | 1023rev |

| Region | Asia |

Wrangel Island (Russian: О́стров Вра́нгеля, romanized: Ostrov Vrangelya, IPA: [ˈostrəf ˈvrangʲɪlʲə]; Chukot: Умӄиԓир, romanized: Umqiḷir, IPA: [umqiɬir], lit. 'island of polar bears')[1] is an island of the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. It is the 92nd largest island in the world and roughly the size of Crete. Located in the Arctic Ocean between the Chukchi Sea and East Siberian Sea, the island lies astride the 180th meridian. The International Date Line is therefore displaced eastwards at this latitude to keep the island, as well as the Chukchi Peninsula on the Russian mainland, on the same day as the rest of Russia. The closest land to Wrangel Island is the tiny and rocky Herald Island located 60 kilometres (32 nmi) to the east.[2] Its straddling the 180th meridian makes its north shore at that point both the northeasternmost and northwesternmost point of land in the world by strict longitude; using the International Date Line instead those respective points become Herald Island and Alaska's Cape Lisburne.

Most of Wrangel Island, with the adjacent Herald Island, is a federally protected nature sanctuary administered by Russia's Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment. In 1976, Wrangel Island and all of its surrounding waters were classified as a "zapovednik" (a "strict nature reserve") and, as such, receive the highest level of protection, excluding virtually all human activity other than conservation research and scientific purposes. In 1999, the Chukotka Regional government extended the protected marine area to 24 nmi (44 km) offshore. As of 2003, there were four rangers who reside on the island year-round, while a core group of about 12 scientists conduct research during the summer months. Wrangel Island was home to the last surviving population of woolly mammoths, with radiocarbon dating suggesting the species persisted on the island until around 4,000 years ago.

The natural complex of the Wrangel Island Reserve has been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List since 2004.

Toponymy

Captain Thomas Long named Wrangel Island for Baron Ferdinand von Wrangel, who was a Baltic German explorer and Admiral in the Imperial Russian Navy. Captain Long, published in The Honolulu Advertiser, November 1867:

I have named this northern land Wrangell Land as an appropriate tribute to the memory of a man who spent three consecutive years north of latitude 68°, and demonstrated the problem of this open polar sea forty-five years ago, although others of much later date have endeavored to claim the merit of this discovery.[3]

Baron von Wrangel never managed to visit the island. Wrangel had noticed swarms of birds flying north, and, questioning the native population, determined that there must be an island undiscovered by Europeans existing in the Arctic Ocean. He searched for it during his Kolymskaya expedition (1823–1824), but failed to find it.

Geography

Wrangel Island is about 150 km (93 mi) long from east to west and 80 km (50 mi) wide from north to south, with an area of 7,600 km2 (2,900 sq mi). It is separated from the Siberian mainland by the Long Strait, and the island itself is a landmark separating the East Siberian Sea from the Chukchi Sea on the northern end. The distance to the closest point on the mainland is 140 km (87 mi).[4]

The island's topography consists of a southern coastal plain that is on average 15 km (9.3 mi) wide; a 40 km (25 mi) wide east-west trending central belt of low-relief mountains, with the highest elevations at the Tsentral'nye Mountain Range; and a roughly 25 km (16 mi) wide northern coastal plain. The highest mountain on this island is Gora Sovetskaya with an elevation of 1,096 m (3,596 ft) above mean sea level, although mostly the mountains are a little over 500 m (1,600 ft) above mean sea level. The island's mountain ranges terminate at sea cliffs at either end of the island.[2] Blossom Point is the westernmost point and Waring Point (Mys Uering) the easternmost point of the island. Despite its mountainous terrain and high latitude, Wrangel Island is not glaciated.

Wrangel Island belongs administratively to the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug of the Russian Federation. The island has a weather station at Blossom Point and, formerly, two Chukchi fishing settlements on the southern side of the island (Ushakovskoye[2] and Zvyozdny on the shore of Somnitelnaya Bay[5]).

Geology

Wrangel Island consists of folded, faulted, and metamorphosed volcanic, intrusive, and sedimentary rocks ranging in age from Upper Precambrian to Lower Mesozoic. The Precambrian rocks, which are about 2 km (6,600 ft) thick, consist of Upper Proterozoic sericite and chlorite slate and schist that contain minor amounts of metavolcanic rocks, metaconglomerates, and quartzite. These rocks are intruded by metamorphosed gabbro, diabase, and felsic dikes and sills and granite intrusions. Overlying the Precambrian strata are up to 2.25 km (7,400 ft) of Upper Silurian to Lower Carboniferous consisting of interbedded sandstone, siltstone, slate, argillite, some conglomerate and rare limestone and dolomite. These strata are overlain by up to 2.15 km (7,100 ft) of Carboniferous to Permian limestone, often composed largely of crinoid plates, that is interbedded with slate, argillite and locally minor amounts of thick breccia, sandstone, and chert. The uppermost stratum consists of 0.7 to 1.5 km (2,300 to 4,900 ft) of Triassic clayey quartzose turbidites interbedded with black slate and siltstone.[2]

A thin veneer of Cenozoic gravel, sand, clay and mud underlie the coastal plains of Wrangel Island. Late Neogene clay and gravel, which are only a few tens of meters thick, rest upon the eroded surface of the folded and faulted strata that compose Wrangel Island. Indurated Pliocene mud and gravel, which are only a few meters thick, overlie the Late Neogene sediments. Sandy Pleistocene sediments occur as fluvial sediments along rivers and streams and as a very thin and patchy surficial layer of either colluvium or eluvium.[2]

- Wrangel Island coastline

Flora and fauna

Wrangel Island is a breeding ground for polar bears—having the highest density of dens in the world—bearded and ringed seals, walrus, as well as collared and west and east Siberian lemmings, a major food source for terrestrial carnivores, namely the Arctic foxes, wolverines and wolves which also inhabit the island. Cetaceans, such as Arctic bowhead whales, migratory gray whales and belugas can be seen close to shore.

Woolly mammoths survived on the island until around 2500–2000 BC, the most recent survival of any known mammoth populations; for perspective, these mammoths were living during the times of ancient Bronze Age civilizations such as Sumer, Elam and the Indus Valley. This was also the time of the fourth dynasty of Ancient Egypt.[6][4][7][8] Mammoths, apparently, died out and subsequently disappeared from mainland Eurasia and North America around 10,000 years ago; however, about 500–1,000 mammoths were isolated on Wrangel Island and thus continued to survive for another 6,000 years.[9]

Domestic reindeer were introduced in the 1950s, and their feral numbers are managed at around 1,000 in an effort to reduce their impact on nesting bird grounds. In 1975, musk oxen were also introduced, with a population that has grown from 20 to about 1,000 animals.[10] In 2002, wolves were spotted on the island, a significant sighting as the canids were present on the island in ancient times.[11]

The flora of the island includes 417 species of plants, double that of any other Arctic tundra territory, of comparable size, and more than any other Arctic island. Thus, the island was proclaimed the northernmost World Heritage Site in 2004. Species and genera present include various Arctic-adapted types of Androsace, Artemisia, Astragalus, Carex, Cerastium, Draba, Erigeron, Oxytropis, Papaver, Pedicularis, Potentilla, Primula, Ranunculus, Rhodiola, Rumex, Salix, Saxifraga, Silene and Valeriana, among others.[12]

Important Bird Area

Wrangel Island, along with nearby Herald Island, has been designated an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International as it supports breeding colonies of many species of birds, including geese such as brant, cackling, greater white-fronted, Ross' and snow geese, and snowy owls[13]—another Arctic predator attracted by the island's lemmings (which the owls can hear tunneling beneath the snow, catching the rodents with adept proficiency). Several gull species are present, including glaucous, Ross', Sabine's and ivory gulls, long-tailed, pomarine and parasitic jaegers, and black-legged kittiwakes,[13] as well as many other sea and shorebird species, such as common and king eiders, horned puffins, pelagic cormorants, long-tailed ducks, red phalarope, dunlin, pectoral sandpipers, ruddy turnstones, red knots, black-bellied plovers, thick-billed murres and black guillemots.[14] Passerine birds, though few, include Arctic warblers, Lapland longspurs and snow buntings.[13] Wrangel Island is possibly the furthest-north that a sandhill crane has been observed, in 2014.[15]

Climate

Wrangel Island has a severe polar climate (Köppen ET). The region is blanketed by dry and cold Arctic air masses for most of the year. Warmer and more humid air can reach the island from the south-east during summer. Dry and heated air from Siberia comes to the island periodically.

Wrangel Island is influenced by both the Arctic and Pacific air masses. One consequence is the predominance of high winds. The island is subjected to "cyclonic" episodes characterized by rapid circular winds. It is also an island of mists and fogs.

Winters are prolonged and are characterized by steady frosty weather and high northerly winds. During this period, the temperatures usually stay well below freezing for months. In February and March there are frequent snow-storms with wind speeds of 40 m/s (140 km/h; 89 mph) or above.

There are noticeable differences in climate between the northern, central and southern parts of the island. The central and southern portions are warmer, with some of their valleys having semi-continental climates that support a number of sub-Arctic steppe-like meadow species. This area has been described as perhaps being a relict of the Ice Age mammoth steppe, along with certain areas along the northwestern border between Mongolia and Russia.

The short summers are cool but comparatively mild as the polar day generally keeps temperatures above 0 °C (32 °F). Some frosts and snowfalls occur, and fog is common. Warmer and drier weather is experienced in the center of the island because the interior's topography encourages foehn winds. As of 2003, the frost-free period on the island was very short, usually not more than 20 to 25 days, and more often only two weeks. Average relative humidity is about 83%.

| Climate data for Wrangel Island | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

0.2 (32.4) |

2.5 (36.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

18.2 (64.8) |

16.7 (62.1) |

12.7 (54.9) |

9.3 (48.7) |

5.4 (41.7) |

2.0 (35.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | −18.5 (−1.3) |

−18.7 (−1.7) |

−17.4 (0.7) |

−11.7 (10.9) |

−2.5 (27.5) |

3.8 (38.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−15.5 (4.1) |

−6.4 (20.5) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | −21.8 (−7.2) |

−22.2 (−8.0) |

−21.0 (−5.8) |

−15.2 (4.6) |

−5.1 (22.8) |

1.2 (34.2) |

3.6 (38.5) |

3.2 (37.8) |

1.0 (33.8) |

−4.2 (24.4) |

−10.8 (12.6) |

−18.2 (−0.8) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −25.1 (−13.2) |

−25.7 (−14.3) |

−24.5 (−12.1) |

−18.8 (−1.8) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

1.4 (34.5) |

1.4 (34.5) |

−0.7 (30.7) |

−6.3 (20.7) |

−13.5 (7.7) |

−21.0 (−5.8) |

−11.7 (10.8) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −42.0 (−43.6) |

−44.6 (−48.3) |

−45.0 (−49.0) |

−38.2 (−36.8) |

−31.5 (−24.7) |

−12.3 (9.9) |

−4.9 (23.2) |

−6.5 (20.3) |

−14.6 (5.7) |

−29.8 (−21.6) |

−34.9 (−30.8) |

−57.7 (−71.9) |

−57.7 (−71.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 9.1 (0.36) |

10.2 (0.40) |

7.6 (0.30) |

6.7 (0.26) |

7.9 (0.31) |

9.3 (0.37) |

21.5 (0.85) |

22.3 (0.88) |

16.3 (0.64) |

16.1 (0.63) |

11.5 (0.45) |

9.4 (0.37) |

147.9 (5.82) |

| Average rainy days | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.3 | 4 | 9 | 14 | 17 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 0.2 | 59 |

| Average snowy days | 13 | 13 | 12 | 14 | 17 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 15 | 22 | 16 | 13 | 153 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 79 | 80 | 80 | 81 | 85 | 87 | 88 | 89 | 86 | 81 | 79 | 79 | 83 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 2 | 59 | 195 | 267 | 199 | 233 | 226 | 125 | 73 | 50 | 4 | 0 | 1,433 |

| Source 1: Климат о. Врангеля[16] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: NOAA (sun 1961–1990)[17] | |||||||||||||

Waters on and around Wrangel

According to a 2003 report prepared by the Wrangel Island Nature Preserve, the hydrographic network of Wrangel Island consists of approximately 1,400 rivers over 1 km (0.62 mi) in length; five rivers over 50 kilometres (31.07 mi) long; and approximately 900 shallow lakes, mostly located in the northern portion of Wrangel Island, with a total surface area of 80 km2 (31 sq mi). The waters of the East Siberian Sea and the Sea of Chukchi surrounding Wrangel and Herald Islands are classified as a separate chemical oceanographic region. These waters have among the lowest levels of salinity in the Arctic basin as well as a very high oxygen content and increased biogenic elements.

History

Extinction of the woolly mammoth and first human presence

This remote Arctic island is believed to have been the final place on Earth to support woolly mammoths as an isolated population until their extinction about 2000 BC, which makes them the most recent surviving population known to science.[9][18][19][20] Initially, it was assumed that this was a specific insular dwarf variant of the species originating from Siberia. However, after further evaluation, while their body size is relatively small, it falls within the size range known for woolly mammoths in mainland Siberia, and thus these Wrangel Island mammoths are no longer considered to have been true dwarves (though true dwarf mammoths and other dwarf elephants are known from other islands, some considerably smaller than Wrangel Island mammoths).[21][22]

Research published in 2017 suggested that the mammoth population was experiencing a genetic meltdown in the DNA of the last animals, a difference when compared with examples about 40,000 years earlier, when populations were plentiful. The research suggests the signature of a genomic meltdown in small populations, consistent with nearly neutral genome evolution. It also suggests large numbers of detrimental variants collecting in pre-extinction genomes, a warning for continued efforts to protect current endangered species with small population sizes.[23] However, this conclusion regarding the mammoth population was disputed in 2024, who found that many of the most deleterious mutations had been purged from the genome, and instead suggested that the extinction was likely due to a catastrophic event, and that the woolly mammoths were already extinct for several centuries prior to the earliest human presence on the island.[24] The earliest evidence of humans (and the only known pre-modern archaeological site on the island) is Chertov Ovrag on the southern coast, a Paleoeskimo short-term hunting camp which dates to around 3,600 years ago. At the camp remains of birds (including the remains of at least 32 snow goose, six long-tailed duck, and one individual each of common murre and snow bunting), as well as two seals (including one bearded seal), a walrus and a polar bear were found in association with stone tools,[25] as well as a toggling harpoon head made of walrus tusk. The tools show cultural similarities to other contemporaneous Paleoeskimo sites in Alaska.[26]

A legend prevalent among the Chukchi people of Siberia tells of a chief Krachai (or Krächoj, Krahay, Khrakhai), who fled with his people (the Krachaians or Krahays, also identified as the Onkilon or Omoki – Siberian Yupik people) across the ice to settle in a northern land.[27][28] Though the story may be mythical, the existence of an island or continent to the north was lent credence by the annual migration of reindeer across the ice, as well as the appearance of slate spear-points washed up on Arctic shores, made in a fashion unknown to the Chukchi. Retired University of Alaska, Fairbanks, linguistics professor Michael E. Krauss has presented archaeological, historical, and linguistic evidence that Wrangel Island was a way station on a trade route linking the Inuit settlement at Point Hope, Alaska with the north Siberian coast, and that the coast was colonized in late prehistoric and early historic times by Inuit settlers from North America. Krauss suggests that the departure of these colonists was related to the Krachai legend.[29]

Outside discovery

In 1764, the Cossack Sergeant Stepan Andreyev claimed to have sighted this island. Calling it Tikegen Land, Andreyev found evidence of its inhabitants, the Krahay. Eventually, the island was named after Baron Ferdinand von Wrangel, who, after reading Andreyev's report and hearing Chukchi stories of land at the island's coordinates, set off on an expedition (1820–1824) to discover the island, with no success.[30]

British, American, and Russian expeditions

In 1849, Henry Kellett, captain of HMS Herald, landed on and named it Herald Island. He erroneously thought he saw another island to the west, which he called Plover Island; thereafter it was indicated on British admiralty charts as Kellett Land.

Eduard Dallmann, a German whaler, reported in 1881 that he had landed on the island in 1866.[31]

In August 1867, Thomas Long, an American whaling captain, "approached it as near as fifteen miles. I have named this northern land Wrangell [sic] Land ... as an appropriate tribute to the memory of a man who spent three consecutive years north of latitude 68°, and demonstrated the problem of this open polar sea forty-five years ago, although others of much later date have endeavored to claim the merit of this discovery." An account appeared in the Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 1868 (17th Meeting, at Chicago), published in 1869, under the title "The New Arctic Continent, or Wrangell's Land, discovered 14 August 1867, by Captain Long, of the American Ship Nile, and seen by Captains Raynor, Bliven and others, with a brief Notice of Baron Wrangell's Exploration in 1823".[32]

George W. DeLong, commanding USS Jeannette, led an expedition in 1879 attempting to reach the North Pole, expecting to go by the "east side of Kellett land", which he thought extended far into the Arctic. His ship became locked in the polar ice pack and drifted westward, passing within sight of Wrangel before being crushed and sunk in the vicinity of the New Siberian Islands.

A party from the USRC Corwin landed on Wrangel Island on 12 August 1881, claimed the island for the United States and named it "New Columbia".[33] The expedition, under the command of Calvin L. Hooper, was seeking the Jeannette and two missing whalers in addition to conducting general exploration. It included naturalist John Muir, who published the first description of Wrangel Island. In the same year on 23 August, the USS Rodgers, commanded by Lieutenant R. M. Berry during the second search for the Jeannette, landed a party on Wrangel Island which stayed about two weeks and conducted an extensive survey of the southern coast.[34]

In 1911, the Russian Arctic Ocean Hydrographic Expedition on icebreakers Vaygach and Taymyr under Boris Vilkitsky, landed on the island.[35] In 1916 the Tsarist government declared that the island belonged to the Russian Empire.

Stefansson expeditions

In 1914, members of the Canadian Arctic Expedition, organized by Vilhjalmur Stefansson, were marooned on Wrangel Island for nine months after their ship, Karluk, was crushed in the ice pack.[36] The survivors were rescued by the American motorized fishing schooner King & Winge[37] after Captain Robert Bartlett walked across the Chukchi Sea to Siberia to summon help.

In 1921, Stefansson sent five settlers (the Canadian Allan Crawford, three Americans: Fred Maurer, Lorne Knight and Milton Galle, and Iñupiat seamstress and cook Ada Blackjack) to the island in a speculative attempt to claim it for Canada.[38] [39] The explorers were handpicked by Stefansson based upon their previous experience and academic credentials. Stefansson considered those with advanced knowledge in the fields of geography and science for this expedition. At the time, Stefansson claimed that his purpose was to head off a possible Japanese claim.[40] An attempt to relieve this group in 1922 failed when the schooner Teddy Bear under Captain Joe Bernard became stuck in the ice.[41] In 1923, the sole survivor of the Wrangel Island expedition, Ada Blackjack, was rescued by a ship that left another party of 13 (American Charles Wells and 12 Inuit).[38]

In 1924, the Soviet Union removed the American and 13 Inuit (one was born on the island) of this settlement aboard the Krasny Oktyabr (Red October). Wells subsequently died of pneumonia in Vladivostok during a diplomatic American-Soviet row about an American boundary marker on the Siberian coast, and so did an Inuit child. The others were deported from Vladivostok to the Chinese border post Suifenhe, but the Chinese government did not want to accept them as the American consul in Harbin told them the Inuit were not American citizens. Later, the American government came up with a statement that the Inuit were 'wards' of the United States, but that there were no funds for returning them. Eventually, the American Red Cross came up with $1,600 for their return. They subsequently moved through Dalian, Kobe and Seattle (where another Inuit child drowned during the wait for the return trip to Alaska) back to Nome.[42]

During the Soviet trip, the American reindeer owner Carl J. Lomen from Nome had taken over the possessions of Stefansson and had acquired explicit support ("go and hold it") from US Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes to claim the island for the United States,[43] a goal about which the Russian expedition got to hear during their trip. Lomen dispatched the MS Herman, commanded by captain Louis L. Lane. Due to unfavorable ice conditions, the Herman could not get any further than Herald Island, where the American flag was raised.[44]

In 1926, the government of the Soviet Union reaffirmed the Tsarist claim to sovereignty over Wrangel Island.

Soviet administration

In 1926, a team of Soviet explorers, equipped with three years of supplies, landed on Wrangel Island. Clear waters that facilitated the 1926 landing were followed by years of continuous heavy ice surrounding the island. Attempts to reach the island by sea failed, and it was feared that the team would not survive their fourth winter.[45]

In 1929, the icebreaker Fyodor Litke was chosen for a rescue operation. It sailed from Sevastopol, commanded by captain Konstantin Dublitsky. On 4 July, it reached Vladivostok where all Black Sea sailors were replaced by local crew members. Ten days later Litke sailed north; it passed the Bering Strait, and tried to pass Long Strait and approach the island from south. On 8 August a scout plane reported impassable ice in the strait, and Litke turned north, heading to Herald Island. It failed to escape mounting ice; on August 12 the captain shut down the engines to save coal and had to wait two weeks until the ice pressure eased. Making a few hundred meters a day, Litke reached the settlement August 28. On September 5, Litke turned back, taking all the 'islanders' to safety. This operation earned Litke the order of the Red Banner of Labour (January 20, 1930), as well as commemorative badges for the crew.

According to a 1936 article in Time magazine, Wrangel Island became the scene of a bizarre criminal story in the 1930s when it fell under the increasingly arbitrary rule of its appointed governor Konstantin Semenchuk. Semenchuk controlled the local populace and his own staff through open extortion and murder. He forbade the local Yupik Eskimos (recruited from Provideniya Bay in 1926)[46] to hunt walrus, which put them in danger of starvation, while collecting food for himself. He was then implicated in the mysterious deaths of some of his opponents, including the local doctor. Allegedly, he ordered his subordinate, the sledge driver Stepan Startsev, to murder Dr. Nikolai Vulfson, who had attempted to stand up to Semenchuk, on 27 December 1934 (though there were also rumours that Startsev had fallen in love with Vulfson's wife, Dr. Gita Feldman, and killed him out of jealousy).[47] The subsequent trial in May–June 1936, at the Supreme Court of the RSFSR, sentenced Semenchuk and Startsev to death for "banditry" and violation of Soviet law, and "the most publicised result of the trial was the joy of the liberated Eskimos".[48][49] This trial had the result of launching the career of the prosecutor, Andrey Vyshinsky, who called the two defendants "human waste" and who would soon achieve great notoriety in the Moscow Trials.

In 1948, a small herd of domestic reindeer was introduced with the intention of establishing commercial herding to generate income for island residents.

Aside from the main settlement of Ushakovskoye near Rogers Bay, on the south-central coast, in the 1960s a new settlement named Zvyozdny was established some 38 km (24 mi) to the west in the Somnitelnaya Bay area, where ground runways reserved for military aviation were constructed (these were abandoned in the 1970s). Moreover, a military radar installation was built on the southeast coast at Cape Hawaii. Rock crystal mining had been carried out for a number of years in the center of the island near Khrustalnyi Creek. At the time, a small settlement, Perkatkun, had been established nearby to house the miners, but later on it was completely destroyed.

Establishment of Federal Nature Reserve

Resolution #189 of the Council of Ministers of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) was adopted on 23 March 1976, for the establishment of the state Nature Reserve "Wrangel Island" for the purpose of conserving the unique natural systems of Wrangel and Herald Islands and the surrounding waters out to 5 nmi (9 km). On 15 December 1997, the Russian Government's Decree No. 1623-r expanded the marine reserve out to 12 nmi (22 km). On 25 May 1999, the (regional) Governor of Chukotka issued Decree No. 91, which again expanded the protected water area to 24 nmi (44 km) around Wrangel and Herald Islands.

By the 1980s, the reindeer-herding farm on Wrangel had been abolished and the settlement of Zvezdnyi was virtually abandoned. Hunting had already been stopped, except for a small quota of marine mammals for the needs of the local population. In 1992, the military radar installation at Cape Hawaii (on the southeast coast) was closed, and only the settlement of Ushakovskoye remained occupied.

Post-Soviet era

According to some American activists and government officials, at least eight Arctic islands currently controlled by Russia, including Wrangel Island, are claimed or should be claimed by the United States.[50][51] However, according to the United States Department of State[52] no such claim exists.[53] The USSR–USA Maritime Boundary Agreement,[54] which has yet to be approved by the Russian Duma, does not specifically address the status of these islands nor the maritime boundaries associated with them.

On 1 June 1990, US Secretary of State James Baker signed an executive agreement with Eduard Shevardnadze, the Soviet foreign minister. It specified that even though the treaty had not been ratified, the U.S. and the USSR agreed to abide by the terms of the treaty beginning 15 June 1990. The Senate ratified the USSR–USA Maritime Boundary Agreement in 1991, which was then signed by President George H. W. Bush.[55]

In 2004, Wrangel Island and neighboring Herald Island, along with their surrounding waters, were added to UNESCO's World Heritage List.[56]

Russian naval base

In 2014, the Russian Navy announced plans to establish a base on the island.[57] The bases on Wrangel Island and on Cape Schmidt on Russia's Arctic coast reportedly consist of two sets of 34 prefabricated modules.[58]

In literature

In Jules Verne's novel César Cascabel, the protagonists float past Wrangel Island on an iceberg. In Verne's description, a live volcano is located on the island: "Between the two capes on its southern coast, Cape Hawan and Cape Thomas, it is surmounted by a live volcano, which is marked on the recent maps."[59] In Chukchi author Yuri Rytkheu's historical novel A Dream in Polar Fog, set in the early 20th century, the Chukchi knew of Wrangel Island and referred to it as the "Invisible Land" or "Invisible Island".[60]

The title poem of Craig Finlay’s 2021 collection The Very Small Mammoths of Wrangel Island describes the last few wooly mammoths living there.[61]

See also

- Russian Arctic islands

- List of islands of Russia

- List of nature reserves in Russia

- World Heritage Sites in Russia

References

- ^ Леонтьев, Владилен Вячеславович; Новикова, Клавдия Александровна (1989). Меновщиков, Георгий Алексеевич (ed.). Топономический словарь Северо-Востока СССР (in Russian). Magadan: Магаданское книжное издательство. pp. 108, 384. ISBN 5-7581-0044-7.

- ^ a b c d e Kosko, M.K., M.P. Cecile, J.C. Harrison, V.G. Ganelin, N.V., Khandoshko, and B.G. Lopatin, 1993, Geology of Wrangel Island, Between Chukchi and East Siberian Seas, Northeastern Russia. Bulletin 461, Geological Survey of Canada, Ottawa Ontario, 101 pp.

- ^ Text by Captain Long published in The Honolulu Advertiser, November 1867

- ^ a b Vartanyan, S.L.; Arslanov, Kh. A.; Tertychnaya, T. V.; Chernov, S. B. (1995). "Radiocarbon Dating Evidence for Mammoths on Wrangel Island, Arctic Ocean, until 2000 BC". Radiocarbon. 37 (1): 1–6. Bibcode:1995Radcb..37....1V. doi:10.1017/S0033822200014703.

- ^ "Ministry of Natural Resources of the russian Federation – History of Wrangel Island". Archived from the original on February 27, 2005. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Wade, Nicolas (March 2, 2017). "The Woolly Mammoth's Last Stand". The New York Times. Retrieved February 25, 2021.

In a remote, mist-wrapped island north of the eastern tip of Siberia, a small group of woolly mammoths became the last survivors of their once thriving species.

- ^ Arslanov, Kh. A.; Cook, G. T.; Gulliksen, Steinar; Harkness, D.D. (1998). "Consensus Dating of Remains from Wrangel Island". Radiocarbon. 40 (1): 289–294. doi:10.1017/S0033822200018166.

- ^ Vartanyan, Sergei L.; Tikhonov, Alexei N.; Orlova, Lyobov A., "The Dynamic of Mammoth Distribution in the Last Refugia in Beringia", Second World of Elephants Congress, (Hot Springs: Mammoth Site, 2005), 195

- ^ a b Shah, Dhruti (February 25, 2021). "Mammoths' extinction not due to inbreeding, study finds". BBC News.

- ^ "State Nature Reserve -Wrangel Island – Peculiarities of the Nature Reserve". eng.ostrovwrangelya.org.

- ^ Natural System of Wrangel Island Reserve Chukotka, Russian Federation, United Nations Environment Program, World Conservation Monitoring Centre. 7 July 2004.

- ^ "Observations - iNaturalist". iNaturalist. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ a b c "Observations - iNaturalist". Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ "Wrangel and Herald Islands". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Observations - iNaturalist". iNaturalist. January 4, 2021. Retrieved March 9, 2024.

- ^ Климат о. Врангеля (in Russian). Weather and Climate (Погода и климат). Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ "Vrangelja Island (Wrangel Island) Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved February 28, 2016.

- ^ Vartanyan, S. L.; Garutt, V. E.; Sher, A. V. (1993). "Holocene dwarf mammoths from Wrangel Island in the Siberian Arctic". Nature. 362 (6418): 337–349. Bibcode:1993Natur.362..337V. doi:10.1038/362337a0. PMID 29633990. S2CID 4249191.

- ^ Vartanyan, S. L. (1995). "Radiocarbon Dating Evidence for Mammoths on Wrangel Island, Arctic Ocean, until 2000 BC". Radiocarbon. 37 (1): 1–6. Bibcode:1995Radcb..37....1V. doi:10.1017/S0033822200014703. ISSN 0033-8222.

- ^ Nyström, Veronica (March 23, 2012), "Microsatellite genotyping reveals end-Pleistocene decline in mammoth autosomal genetic variation", Molecular Ecology, 21 (14): 3391–402, Bibcode:2012MolEc..21.3391N, doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05525.x, PMID 22443459

- ^ Tikhonov, Alexei; Larry Agenbroad; Sergey Vartanyan (2003). "Comparative analysis of the mammoth populations on Wrangel Island and the Channel Islands" (PDF). Deinsea. 9: 415–420. ISSN 0923-9308. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2014.

- ^ Palombo, Maria Rita; Zedda, Marco; Zoboli, Daniel (February 17, 2024). "The Sardinian Mammoth's Evolutionary History: Lights and Shadows". Quaternary. 7 (1): 10. doi:10.3390/quat7010010. ISSN 2571-550X.

- ^ Rogers, Rebekah L.; Slatkin, Montgomery (2017). "Excess of genomic defects in a woolly mammoth on Wrangel Island". PLOS Genetics. 13 (3): e1006601. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006601. PMC 5333797. PMID 28253255.

- ^ Dehasque, Marianne; Morales, Hernán E.; Díez-del-Molino, David; Pečnerová, Patrícia; Chacón-Duque, J. Camilo; Kanellidou, Foteini; Muller, Héloïse; Plotnikov, Valerii; Protopopov, Albert; Tikhonov, Alexei; Nikolskiy, Pavel; Danilov, Gleb K.; Giannì, Maddalena; van der Sluis, Laura; Higham, Tom (June 2024). "Temporal dynamics of woolly mammoth genome erosion prior to extinction". Cell. 187 (14): 3531–3540.e13. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2024.05.033. PMID 38942016.

- ^ D.V. Gerasimov, E.Y. Giria, V.V. Pitul’ko, A.N. Tikhonov New Materials for the Interpretation of the Chertov Ovrag Site on Wrangel Island. Northeast ASIA 203 (2006)

- ^ Bronshtein, Mikhail M.; Dneprovsky, Kirill A.; Savinetsky, Arkady B. (August 3, 2016). Friesen, Max; Mason, Owen (eds.). Ancient Eskimo Cultures of Chukotka. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199766956.013.53.

- ^ Nordenskiöld, Adolf Erik (1881). The voyage of the Vega round Asia and Europe: with a historical review of previous journeys along the north coast of the old world. trans. by Alexander Leslie. London: Macmillan. pp. 443–448.

- ^ Rink, Signe (1905). "A Comparative Study of Two Indian and Eskimo Legends". Proceedings of the International Congress of Americanists: 280.

- ^ Krauss, Michael E. (2005) "Eskimo languages in Asia, 1791 on, and the Wrangel Island-Point Hope connection". Études/Inuit/Studies, vol. 29 (1–2), 2005, pp. 163–185.

- ^ Von Wrangel, Ferdinand Petrovich (1840). Narrative of an expedition to the polar sea, in 1820, 1821, 1822 & 1823. Edited by Major Edward Sabine. James Madden and Company, London. 465 pp.

- ^ Tammiksaar, E.; N.G. Sukhova; I.R. Stone (September 1999). "Hypothesis Versus Fact: August Petermann and Polar Research" (PDF). Arctic. 52 (3): 237–244. doi:10.14430/arctic929.

- ^ Wheildon, William Willder (1869). The new Arctic continent. Salem. Retrieved August 27, 2020 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Muir, John (1917), The Cruise of the Corwin: Journal of the Arctic Expedition of 1881 in search of De Long and the Jeannette. Norman S. Berg, Dunwoody, Georgia. (John Muir's description of the 1881 exploration of Wrangel Island.)

- ^ George W. De Long, Raymond Lee Newcomb, Our Lost Explorers: The Narrative of the Jeannette Arctic Expedition. p. 60

- ^ "Russian Arctic Ocean Hydrographic Expedition (1910-1915) – Beaufort Gyre Exploration Project". whoi.edu.

- ^ Niven, Jennifer, The Ice Master, The Doomed 1913 Voyage of the Karluk. New York: Hyperion Books. 431 pp.

- ^ Newell, Gordon R., 1966, H. W. McCurdy Maritime History of the Pacific Northwest, Seattle, Washington: Superior Publishing.

- ^ a b Rowe, Peter (March 11, 2022). "Vilhjalmur Stefansson, Ada Blackjack and the Canadian invasion of Russia". Canadian Geographic: History. Canadian Geographic. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ Niven, Jennifer (2003). Ada Blackjack: A True Story of Survival in the Arctic. New York: Hyperion Books.[ISBN missing][page needed]

- ^ "Stefansson Claims Wrangle Island for Great Britain; The Expedition He Sent Out Last Fall Has Established Possession, Says Explorer. Timed to Forestal Japan Any Previous Claims of America or Britain Had Lapsed, He Holds. Now Offered to Canada Stefansson Denies That Russia, to Whom the Island Is Allotted on Maps, Has Any Right to It". The New York Times. March 20, 1922. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "New York Times September 25, 1922" (PDF). Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ Kenney, Gerard "When Canada Invaded Russia". The Canadian Encyclopedia

- ^ Dudley-Rowley, Marilyn (1998) "The Outward Course of Empire: The Hard, Cold Lessons from Euro-American Involvement in the Terrestrial Polar Regions" Archived December 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine presented at the Founding Convention of the Mars Society, August 13–16, 1998, University of Colorado, Boulder, Colorado, United States

- ^ "Полярная Почта • Просмотр темы – Визе В.Ю., Моря Советской Арктики". www.polarpost.ru. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "Wrangel Island holds the fate of lost colony". Berkeley Daily Gazette, January 29, 1929, p. 4

- ^ Krupnik, Igor; Chlenov, Mikhail (2007). "The end of 'Eskimo land': Yupik relocation in Chukotka, 1958–1959". Études/Inuit/Studies. 31 (1–2): 59–81. doi:10.7202/019715ar. S2CID 128562871.

- ^ John McCannon, Red Arctic: Polar Exploration and the Myth of the North in the Soviet Union, 1932–1939 (Oxford University Press US, 1998: ISBN 0-19-511436-1), pp. 156–157.

- ^ "Crazy Governor". , vol. XXVI, no. 22 (June 1, 1936).[page needed]

- ^ Yuri Slezkine, Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small Peoples of the North (Cornell University Press, 1994: ISBN 0-8014-8178-3), p. 288.

- ^ Salom, Don Eric (1981). "The United States Claim to Wrangel Island: The Dormancy Should End", California Western International Law Journal: Vol. 11: No. 1, Article 12.

- ^ Dans, Thomas Emanuel. "Opinion | Russia Occupies American Land, Too". WSJ. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, 2003, "Status of Wrangel and Other Arctic Islands". U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C. (Fact sheet on Wrangel Island).

- ^ See also Brooks Jackson, "Alaskan Island Giveaway?", FactCheck.org, 27 March 2012 (accessed 28 July 2017); Carole Fader, "Fact Check: No Alaskan island giveaway to the Russians", The Florida Times-Union, 12 May 2012 (accessed 28 July 2017).

- ^ US Department of State and USSR Minister of Foreign Affairs (1990), 1990 USSR/USA Maritime Boundary Treaty. DOALOS/OLA – United Nations Delimitation Treaties Infobase, New York.

- ^ "US and Soviet letters as posted by State Department Watch". Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "First wave of new properties added to World Heritage List for 2004". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ^ "Russian navy hoists flag on remote Arctic island". en.europeonline-magazine.eu. DPA. August 20, 2014. Retrieved August 20, 2014.; Itar/Tass "Russian Pacific Fleet stations naval base on Wrangel Island"

- ^ "AK Beat: New Russian military bases going up on Arctic island near Alaska". Alaska Dispatch News. September 10, 2014.

- ^ Verne, Jules (1890). "Part 2, Chapter III: Adrift". Caesar Cascabel. trans. by A. Estoclet. New York: Cassell Publishing Company.

- ^ Rytkheu, Yuri (2005). A Dream in Polar Fog. trans. by Ilona Yazhbin Chavasse. Brooklyn, NY: Archipelago Books. pp. 8, 154. ISBN 978-0-9778576-1-6.

- ^ "Book Review: Craig Finlay, The Very Small Mammoths of Wrangel Island. Poems". Pembroke Magazine. December 31, 2021. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

Works cited

- Anonymous (1923). "Wrangel Island". The Geographical Journal. 62 (6): 440–444. Bibcode:1923GeogJ..62..440.. doi:10.2307/1781170. JSTOR 1781170.

External links

![]() Media related to Wrangel Island at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Wrangel Island at Wikimedia Commons

- Anonymous, 2008, Wrangel Island. at the Wayback Machine (archived December 23, 2010)Oceandots.com (aerial image and description of Wrangel Island)

- Pictures from Wrangel Island. Archived May 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine, 2007.

- Bureau of European and Eurasian Affairs, 2003, Status of Wrangel and Other Arctic Islands. U.S. Department of State, Washington, D.C. (Fact sheet on Wrangel Island.)

- Eglin, Libby, 2000, Run For Wrangel. Tourist's account and photography.

- Eime, Roderick, nd, Wrangel Island: Isolation, Desolation and Tragedy. Comments about history and tourism of Wrangel Island.

- Gray, D., 2003, The story of the Canadian Arctic Expedition of 1913–1918. Virtual Museum of Canada, Canadian Museum of Civilization, Gatineau, Quebec. (Includes Loss of the Karluk and Wrangel Island)

- Gualtieri, L., nd, The Late Pleistocene Glacial and Sea Level History of Wrangel Island, Northeast Siberia. Archived July 19, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Quaternary Research Center, University of Washington. (Numerous comments, picture, papers, links, concerning various aspects of Wrangel Island)

- Detailed map of Wrangel Island (click link in list)

- McClanahan, A.J., nd, The Heroine of Wrangel Island. Archived March 3, 2016, at the Wayback Machine LitSite, Alaska. (Article about Ada Blackjack Johnson and Wrangel Island.)

- MacPhee, Ross, nd, Siberian Expedition to Wrangel Island., American Museum of Natural History, New York. (Hunting mammoths on Wrangel Island)

- Muir, John, 1917, The Cruise of the Corwin: Journal of the Arctic Expedition of 1881 in search of De Long and the Jeannette. Norman S. Berg, Dunwoody, Georgia. John Muir's description of the 1881 exploration of Wrangel Island.

- Natural Heritage Protection Fund, 2008, Wrangel Island. Moscow, Russian Federation. (Web page about the Wrangel Island World Heritage Site.)

- Rosse, I.C., 1883, The First Landing on Wrangel Island: With Some Remarks on the Northern Inhabitants. Journal of the American Geographical Society of New York. vol. 15, pp. 163–214. Text files from Project Gutenberg. (Also, available from JSTOR)

- Stefansson, Vilhjalmur, 1921, The friendly Arctic; the story of five years in polar regions G. P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 319 pp.

- UNESCO World Heritage Committee, nd, Natural System of Wrangel Island Reserve. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, New York.

- Russian Refuge published May 2013 National Geographic magazine