Weird Tales

| |

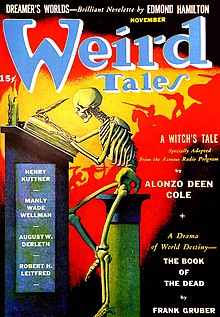

Cover of the March 1942 issue, by Hannes Bok | |

| Categories | |

|---|---|

| Founder | J. C. Henneberger |

| Founded | 1922 |

| First issue | March 1923 |

| Country | United States |

| Website | www |

| OCLC | 55045234 |

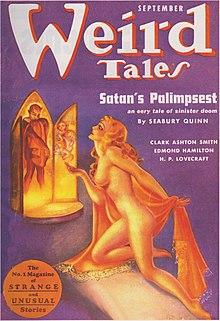

Weird Tales is an American fantasy and horror fiction pulp magazine founded by J. C. Henneberger and J. M. Lansinger in late 1922. The first issue, dated March 1923, appeared on newsstands February 18.[1] The first editor, Edwin Baird, printed early work by H. P. Lovecraft, Seabury Quinn, and Clark Ashton Smith, all of whom went on to be popular writers, but within a year, the magazine was in financial trouble. Henneberger sold his interest in the publisher, Rural Publishing Corporation, to Lansinger, and refinanced Weird Tales, with Farnsworth Wright as the new editor. The first issue to list Wright as editor was dated November 1924. The magazine was more successful under Wright, and despite occasional financial setbacks, it prospered over the next 15 years. Under Wright's control, the magazine lived up to its subtitle, "The Unique Magazine", and published a wide range of unusual fiction.

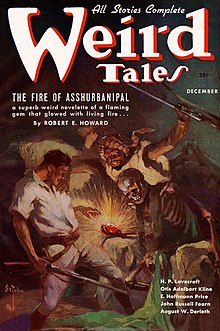

Lovecraft's Cthulhu mythos stories first appeared in Weird Tales, starting with "The Call of Cthulhu" in 1928. These were well-received, and a group of writers associated with Lovecraft wrote other stories set in the same milieu. Robert E. Howard was a regular contributor, and published several of his Conan the Barbarian stories in the magazine, and Seabury Quinn's series of stories about Jules de Grandin, a detective who specialized in cases involving the supernatural, was very popular with the readers. Other well-liked authors included Nictzin Dyalhis, E. Hoffmann Price, Robert Bloch, and H. Warner Munn. Wright published some science fiction, along with the fantasy and horror, partly because when Weird Tales was launched, no magazines were specializing in science fiction, but he continued this policy even after the launch of magazines such as Amazing Stories in 1926. Edmond Hamilton wrote a good deal of science fiction for Weird Tales, though after a few years, he used the magazine for his more fantastic stories, and submitted his space operas elsewhere.

In 1938, the magazine was sold to William Delaney, the publisher of Short Stories, and within two years, Wright, who was ill, was replaced by Dorothy McIlwraith as editor. Although some successful new authors and artists, such as Ray Bradbury and Hannes Bok, continued to appear, the magazine is considered by critics to have declined under McIlwraith from its heyday in the 1930s. Weird Tales ceased publication in 1954, but since then, numerous attempts have been made to relaunch the magazine, starting in 1973. The longest-lasting version began in 1988 and ran with an occasional hiatus for over 20 years under an assortment of publishers. In the mid-1990s, the title was changed to Worlds of Fantasy and Horror because of licensing issues, the original title returning in 1998.

The magazine is regarded by historians of fantasy and science fiction as a legend in the field, Robert Weinberg considering it "the most important and influential of all fantasy magazines".[2] Weinberg's fellow historian, Mike Ashley, describes it as "second only to Unknown in significance and influence",[3] adding that "somewhere in the imagination reservoir of all U.S. (and many non-U.S.) genre-fantasy and horror writers is part of the spirit of Weird Tales".[4]

Background

In the late 19th century, popular magazines typically did not print fiction to the exclusion of other content; they would include nonfiction articles and poetry, as well. In October 1896, Frank A. Munsey Company's Argosy magazine was the first to switch to printing only fiction, and in December of that year, it changed to using cheap wood-pulp paper. This is now regarded by magazine historians as having been the start of the pulp magazine era. For years, pulp magazines were successful without restricting their fiction content to any specific genre, but in 1906, Munsey launched Railroad Man's Magazine, the first title that focused on a particular niche. Other titles that specialized in particular fiction genres followed, starting in 1915 with Detective Story Magazine, with Western Story Magazine following in 1919.[5] Weird fiction, science fiction, and fantasy all appeared frequently in the pulps of the day, but by the early 1920s, still no single magazine was focused on any of these genres, though The Thrill Book, launched in 1919 by Street & Smith with the intention of printing "different", or unusual, stories, was a near miss.[5][6]

In 1922, J. C. Henneberger, the publisher of College Humor and The Magazine of Fun, formed Rural Publishing Corporation of Chicago, in partnership with his former fraternity brother, J. M. Lansinger.[7][8] Their first venture was Detective Tales, a pulp magazine that appeared twice a month, starting with the October 1, 1922 issue. It was initially unsuccessful, and as part of a refinancing plan, Henneberger decided to publish another magazine that would allow him to split some of his costs between the two titles. Henneberger had long been an admirer of Edgar Allan Poe, so he created a fiction magazine that would focus on horror, and titled it Weird Tales.[9][10]

Publication history

Rural Publishing Corporation

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 2/4 | ||||

| 1924 | 3/1 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 3/4 | 4/2 | 4/3 | 4/4 | |||||

| 1925 | 5/1 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 5/4 | 5/5 | 5/6 | 6/1 | 6/2 | 6/3 | 6/4 | 6/5 | 6/6 |

| 1926 | 7/1 | 7/2 | 7/3 | 7/4 | 7/5 | 7/6 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/3 | 8/4 | 8/5 | 8/6 |

| 1927 | 9/1 | 9/2 | 9/3 | 9/4 | 9/5 | 9/6 | 10/1 | 10/2 | 10/3 | 10/4 | 10/5 | 10/6 |

| 1928 | 11/1 | 11/2 | 11/3 | 11/4 | 11/5 | 11/6 | 12/1 | 12/2 | 12/3 | 12/4 | 12/5 | 12/6 |

| 1929 | 13/1 | 13/2 | 13/3 | 13/4 | 13/5 | 13/6 | 14/1 | 14/2 | 14/3 | 14/4 | 14/5 | 14/6 |

| 1930 | 15/1 | 15/2 | 15/3 | 15/4 | 15/5 | 15/6 | 16/1 | 16/2 | 16/3 | 16/4 | 16/5 | 16/6 |

| 1931 | 17/1 | 17/2 | 17/3 | 17/4 | 18/1 | 18/2 | 18/3 | 18/4 | 18/5 | |||

| 1932 | 19/1 | 19/2 | 19/3 | 19/4 | 19/5 | 19/6 | 20/1 | 20/2 | 20/3 | 20/4 | 20/5 | 20/6 |

| 1933 | 21/1 | 21/2 | 21/3 | 21/4 | 21/5 | 21/6 | 22/1 | 22/2 | 22/3 | 22/4 | 22/5 | 22/6 |

| 1934 | 23/1 | 23/2 | 23/3 | 23/4 | 23/5 | 23/6 | 24/1 | 24/2 | 24/3 | 24/4 | 24/5 | 24/6 |

| 1935 | 25/1 | 25/2 | 25/3 | 25/4 | 25/5 | 25/6 | 26/1 | 26/2 | 26/3 | 26/4 | 26/5 | 26/6 |

| 1936 | 27/1 | 27/2 | 27/3 | 27/4 | 27/5 | 27/6 | 28/1 | 28/2 | 28/3 | 28/4 | 28/5 | |

| 1937 | 29/1 | 29/2 | 29/3 | 29/4 | 29/5 | 29/6 | 30/1 | 30/2 | 30/3 | 30/4 | 30/5 | 30/6 |

| 1938 | 31/1 | 31/2 | 31/3 | 31/4 | 31/5 | 31/6 | 32/1 | 32/2 | 32/3 | 32/4 | 32/5 | 32/6 |

| 1939 | 33/1 | 33/2 | 33/3 | 33/4 | 33/5 | 34/1 | 34/2 | 34/3 | 34/4 | 34/5 | 34/6 | |

| 1940 | 35/1 | 35/2 | 35/3 | 35/4 | 35/5 | 35/6 | ||||||

| Issues of Weird Tales from 1923 to 1940, showing volume/issue number. Editors were Edwin Baird (yellow), Farnsworth Wright (blue), and Dorothy McIlwraith (green). There was no issue numbered 4/1.[11] | ||||||||||||

Henneberger chose Edwin Baird, the editor of Detective Tales, to edit Weird Tales; Farnsworth Wright was first reader, and Otis Adelbert Kline also worked on the magazine, assisting Baird. Payment rates were low, usually between a quarter and a half cent per word; the budget went up to one cent per word for the most popular writers.[10] Sales were initially poor, and Henneberger soon decided to change the format from the standard pulp size to large pulp, to make the magazine more visible. This had little long-term effect on sales, though the first issue at the new size, dated May 1923, was the only one that first year to sell out completely—probably because it contained the first instalment of a popular serial, The Moon Terror, by A.G. Birch.[12][13]

Even before the launch, Rural had incurred higher than expected costs from the printer for the first few issues of Detective Tales. After the first issue of Weird Tales, Rural switched to a cheaper printer, but it meant that the magazine began at a financial disadvantage.[14] The magazine lost a considerable amount of money under Baird's editorship: after thirteen issues, the total debt was over $40,000 and perhaps as much as $60,000.[15][notes 1] In the meantime, Detective Tales had been retitled Real Detective Tales and was making a profit, as was College Humor.[10][18] Henneberger decided early in 1924 on a reorganization of the editorial staff, which meant that by late spring Baird was no longer actively editing Weird Tales, though for a while he remained on the staff.[19] A financial reorganization was also necessary, and Henneberger decided to sell both magazines to Lansinger and invest the money in Weird Tales. This did not address the debt, $43,000 of which was owed to the magazine's printer, Cornelius Printing Company. Cornelius agreed to an arrangement in which they would control a new company, to be called Popular Fiction Publishing, until the debt was paid off. Not all of the magazine's debts were eliminated by this transaction, but it meant that Weird Tales could continue to publish, and perhaps return to profitability.[notes 2] The business manager of the new company was William (Bill) Sprenger, who had been working for Rural Publishing. Henneberger had hopes of eventually refinancing the debt with the help of another printer, Hall Printing Company, owned by Robert Eastman,[12][20] though it is not known when Eastman and Henneberger discussed the possibility.[21]

Baird stayed with Lansinger, so Henneberger wrote to H. P. Lovecraft, who had sold some stories to Weird Tales, to see if he would be interested in taking the job. Henneberger offered ten weeks advance pay, but made it a condition that Lovecraft move to Chicago, where the magazine was headquartered. Lovecraft described Henneberger's plans in a letter to Frank Belknap Long as "a brand-new magazine to cover the field of Poe-Machen shudders". Lovecraft did not wish to leave New York, where he had recently moved with his new bride; his dislike of cold weather was another deterrent.[12][22][23][notes 3] He spent several months considering the offer in mid-1924 without making a final decision; Henneberger visited him in Brooklyn more than once, but eventually either Lovecraft declined or Henneberger simply gave up.[12][25] Wright briefly severed his connection with Weird Tales in mid-1924,[26] but by the end of the year he had been hired as its new editor.[12] The last issue under Baird's name was a combined May/June/July issue, with 192 pages—a much thicker magazine than the earlier issues. It was assembled by Wright and Kline, rather than Baird.[12]

Popular Fiction Publishing

Henneberger gave Wright full control of Weird Tales, and did not get involved with story selection. In about 1921, Wright had begun to suffer from Parkinson's disease, and over the course of his editorship the symptoms grew gradually worse. By the end of the 1920s he was unable to sign his name, and by the late 1930s Bill Sprenger was helping him get to work and back home.[12] The first issue with Wright as editor was dated November 1924, and the magazine immediately resumed a regular monthly schedule, the format changing back to pulp again.[11] The pay rate was initially low, with a cap of half a cent per word until 1926, when the top rate was increased to one cent per word. Some of Popular Fiction Publishing's debts were paid off over time, and the highest pay rate eventually rose to one and a half cents per word.[notes 4] The magazine's cover price was high for the time. Robert Bloch recalled that "in the late Twenties and Thirties of this century...at a time when most pulp periodicals sold for a dime, its price was a quarter".[30] Although Popular Fiction Publishing continued to be based in Chicago, the editorial offices were in Indianapolis for a while, at two separate addresses, but moved to Chicago toward the end of 1926. After a short period on North Broadway, the office moved to 840 North Michigan Avenue, where it would remain until 1938.[31]

In 1927, Popular Fiction Publishing issued Birch's The Moon Terror, one of Weird Tales' more popular serials, as a hardcover book, including three other stories from the magazine's first year. One of the stories, "An Adventure in the Fourth Dimension", was by Wright himself. The book sold poorly, and it remained on offer in the pages of Weird Tales, at reduced prices, for twenty years.[31][32] It was at one point provided as a bonus to readers who subscribed.[33] In 1930 Cornelius launched a companion magazine, Oriental Stories, but the magazine was not a success, though it managed to last for over three years before Cornelius gave up.[31][34] Another financial blow occurred in late 1930 when a bank failure froze most of the magazine's cash. Henneberger changed the schedule to bimonthly, starting with the February/March 1931 issue; six months later, with the August 1931 issue, the monthly schedule returned.[35] Two years later Weird Tales' bank was still having financial problems, and payment to authors was being substantially delayed.[36]

The Depression also hit the Hall Printing Company, which Henneberger had been hoping would take over the debt from Cornelius; Robert Eastman, the owner of Hall, at one point was unable to meet payroll. Eastman died in 1932, and with him went Henneberger's plans for recovering control of Weird Tales.[21][31] The magazine advertised in the early science fiction pulps, usually highlighting one of the more science-fictional stories. Often the advertised story was by Edmond Hamilton, who was popular in the sf magazines. Wright also sold hardcovers of books by some of his more popular authors, such as Kline, in the pages of Weird Tales.[37] Although the magazine was never greatly profitable, Wright was paid well. Robert Weinberg, author of a history of Weird Tales, records a rumor that Wright was unpaid for much of his work on the magazine, but according to E. Hoffmann Price, a close friend of Wright's who occasionally read manuscripts for him, Weird Tales was paying Wright about $600 a month in 1927.[31]

Delaney

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941 | 35/7 | 35/8 | 35/9 | 35/10 | 36/1 | 36/2 | ||||||

| 1942 | 36/3 | 36/4 | 36/5 | 36/6 | 36/7 | 36/8 | ||||||

| 1943 | 36/9 | 36/10 | 36/11 | 36/12 | 37/1 | 37/2 | ||||||

| 1944 | 37/3 | 37/4 | 37/5 | 37/6 | 38/1 | 38/2 | ||||||

| 1945 | 38/3 | 38/4 | 38/5 | 38/6 | 39/1 | 39/2 | ||||||

| 1946 | 39/3 | 39/4 | 39/5 | 39/6 | 39/7 | 39/8 | ||||||

| 1947 | 39/9 | 39/10 | 39/11 | 39/11 | 39/12 | 40/1 | ||||||

| 1948 | 40/2 | 40/3 | 40/4 | 40/5 | 40/6 | 41/1 | ||||||

| 1949 | 41/2 | 41/3 | 41/4 | 41/5 | 41/6 | 42/1 | ||||||

| 1950 | 42/2 | 42/3 | 42/4 | 42/5 | 42/6 | 43/1 | ||||||

| 1951 | 43/2 | 43/3 | 43/4 | 43/5 | 43/6 | 44/1 | ||||||

| 1952 | 44/2 | 44/3 | 44/4 | 44/5 | 44/6 | 44/7 | ||||||

| 1953 | 44/8 | 45/1 | 45/2 | 45/3 | 45/4 | 45/5 | ||||||

| 1954 | 45/6 | 46/1 | 46/2 | 46/3 | 46/4 | |||||||

| Issues of Weird Tales from 1941 to 1954, showing volume/issue number. (1) The primary editor was Dorothy McIlwraith. Associate editor Lamont Buchanan (red) had primary editing responsibilities from about summer 1945 through his resignation in 1949. The last issue to list him on the masthead is September 1949. The issue marking the precise start of his editorship is currently unknown.[38] (2) The apparent error in duplicating volume 39/11 is in fact correct.[11] | ||||||||||||

In 1938 Popular Fiction Publishing was sold to William J. Delaney, who was the publisher of Short Stories, a successful general fiction pulp magazine based in New York. Sprenger and Wright both received a share of the stock from Cornelius; Sprenger did not remain with the company but Wright moved to New York and stayed on as editor.[35][37] Henneberger's share of Popular Fiction Publishing was converted to a small interest in the new company, Weird Tales, Inc., a subsidiary of Delaney's Short Stories, Inc.[11][37] Dorothy McIlwraith, the editor of Short Stories, became Wright's assistant, and over the next two years Delaney tried to increase profits by adjusting the page count and price. An increase from 144 pages to 160 pages starting with the February 1939 issue, along with the use of cheaper (and hence thicker) paper, made the magazine thicker, but this failed to increase sales. In September 1939 the page count went down to 128, and the price was cut from 25 cents to 15 cents. From January 1940 the frequency was reduced to bimonthly, a change which stayed in effect until the end of the magazine's run fourteen years later.[35][37] None of these changes had the intended effect, and sales continued to languish.[37] In March 1940, Wright was let go because of his increasing health problems—he was by now suffering from Parkinson's so severely that he had trouble walking unassisted. and was replaced by McIlwraith as editor.[39][40][notes 5] Wright then had an operation to reduce the pain with which he suffered, but never fully recovered. He died in June of that year.[12]

Wright was replaced by McIlwraith, whose first issue was dated April 1940. From 1945[42] through 1949,[43] she was assisted by Lamont Buchanan, who worked for her as associate editor and art editor for both Weird Tales and Short Stories. August Derleth also provided assistance and advice, although he had no formal connection with the magazine. Most of McIlwraith's budget went to Short Stories, since that was the more successful magazine;[37][41] the payment rate for fiction in Weird Tales by 1953 was one cent per word, well below the top rates of other science fiction and fantasy magazines of the day.[44] War shortages also caused problems, and the page count was reduced, first to 112 pages in 1943, and then to 96 pages the following year.[37][41]

The price was increased to 20 cents in 1947, and again to 25 cents in 1949, but it was not only Weird Tales that was suffering—the entire pulp industry was in decline. Delaney switched the format to digest with the September 1953 issue, but there was to be no reprieve. In 1954, Weird Tales and Short Stories ceased publication; in both cases the last issue was dated September 1954.[37][45] For Weird Tales, the September 1954 issue was its 279th.[46]

1970s and early 1980s

| Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | 47/1 | 47/2 | 47/3 | |||||||||

| 1974 | 47/4 | |||||||||||

| 1981 | 1 & 2 | 3 | ||||||||||

| 1983 | 4 | |||||||||||

| 1984 | 49/1 | |||||||||||

| 1985 | 49/2 | |||||||||||

| 1988 | 50/1 | 50/2 | 50/3 | 50/4 | ||||||||

| 1989 | 51/1 | 51/2 | ||||||||||

| 1990 | 51/3 | 51/4 | 52/1 | 52/2 | ||||||||

| 1991 | 52/3 | 52/4 | 53/1 | 53/2 | ||||||||

| 1992 | 53/3 | 53/4 | ||||||||||

| 1993 | 53/3 | 53/3 | ||||||||||

| 1994 | 53/3 | 1/1 | ||||||||||

| 1995 | 1/2 | |||||||||||

| 1996 | 1/3 | 1/4 | ||||||||||

| 1998 | 55/1 | 55/2 | ||||||||||

| 1999 | 55/3 | 55/4 | 56/1 | 56/2 | ||||||||

| 2000 | 56/3 | 56/4 | 57/1 | 57/2 | ||||||||

| 2001 | 57/3 | 57/4 | 58/1 | 58/2 | ||||||||

| 2002 | 58/3 | 58/4 | 59/1 | 59/2 | ||||||||

| Issues of Weird Tales from 1988 to 2002, showing volume and issue numbers. Note that the four issues starting with Summer 1994 were titled Worlds of Fantasy & Horror. Five of the Winter issues were dated with two years: 1988/1989, 1992/1993; 1996/1997, 2001/2002, and 2002/2003. Editors were Moskowitz (gray), Carter (purple), Ackerman & Lamont (bright pink), Garb (green), Schweitzer, Scithers and Betancourt (orange); Schweitzer (dark pink); and Scithers and Schweitzer (yellow).[47] | ||||||||||||

In the mid-1950s, Leo Margulies, a well-known figure in the magazine publishing world, launched a new company, Renown Publications, with plans to publish several titles. He acquired the rights to both Weird Tales and Short Stories, and hoped to bring both magazines back. He abandoned a plan to restart Weird Tales in 1962, using reprints from the original magazine, after being advised by Sam Moskowitz that there was little market for weird and horror fiction at the time.[48][notes 6] Instead Margulies mined the Weird Tales backfile for four anthologies which appeared in the early 1960s: The Unexpected, The Ghoul-Keepers, Weird Tales, and Worlds of Weird.[49] The latter two were ghost-edited by Moskowitz, who proposed to Margulies that when the time was right to start the magazine up again, it should include reprints from obscure sources that Moskowitz had found, rather than just stories reprinted from the first incarnation of Weird Tales.[49][51] These stories would be as good as new for most readers, and the money saved could be used for an occasional new story.[49]

The new version of Weird Tales finally appeared from Renown Publications, in April 1973, edited by Moskowitz. It had weak distribution and sales were too low for sustainability; according to Moskowitz the average sales were 18,000 copies per issue, well short of the 23,000 that would have been needed for the magazine to survive. The fourth issue, dated Summer 1974, was the last, as Margulies closed down all his magazines except for Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, which was the only one that was making a profit. Mike Ashley, a science fiction magazine historian, records that Moskowitz was unwilling to continue in any case, as he was annoyed by Margulies's detailed involvement in the day-to-day editorial tasks such as editing manuscripts and writing introductions.[49]

Margulies died the following year, and his widow, Cylvia Margulies, decided to sell the rights to the title. Forrest Ackerman, a science fiction fan and editor, was one of the interested parties, but she chose instead to sell to Victor Dricks and Robert Weinberg.[52] Weinberg in turn licensed the title to Lin Carter, who interested a publisher, Zebra Books, in the project. The result was a series of four paperback anthologies, edited by Lin Carter, appearing between 1981 and 1983;[53] these were originally planned to be quarterly, but in fact the first two both appeared in December 1980 and were both dated Spring 1981. The next was dated Fall 1981;[54] Carter's rights to the title were terminated by Weinberg in 1982 for non-payment, but the fourth issue was already in the works and finally appeared with a date of Summer 1983.[55]

In 1982 Sheldon Jaffery and Roy Torgeson met with Weinberg to propose taking over as licensees, but Weinberg decided not to pursue the offer. The following year, Brian Forbes approached Weinberg with another offer. Forbes' company, the Bellerophon Network, was an imprint of a Los Angeles company named The Wizard. Ashley reports that Weinberg was only able to contact Forbes by phone, and even that was not always reliable, so negotiations were slow. Forbes' editorial director was Gordon Garb and the fiction editor was Gil Lamont; Forrest Ackerman also assisted, mainly by obtaining material to include. There was a good deal of confusion between the participants in the project:[56] according to Locus, a science fiction trade journal, "Ackerman says he has had no contact with publisher Forbes, does not know what will happen to the material he put together, and is as much in the dark as everybody else. Lamont says that he is still renegotiating his contract and is not sure where he stands".[57] The original plan was for the first issue to appear in August 1984, dated July/August, but before it appeared the decision was taken to change the contents, and a new, completely reset issue finally appeared at the end of the year, dated Fall 1984. Even with this delay a final agreement had not yet been reached with Weinberg over licensing. Only 12,500 copies were printed; these were sent to two distributors who both went into bankruptcy. As a result, few copies were sold, and Forbes was not paid by the distributors. Despite the financial setback, Forbes attempted to continue, and a second issue eventually appeared. Its cover date was Winter 1985 but it was not published until June 1986. Few copies were printed; reports vary between 1,500 and 2,300 in total. Mark Monsolo was the fiction editor, but Garb continued as editorial director; Lamont was no longer involved with the magazine.[56]

Terminus and successors

| Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

| 2003 | 59/3 | 59/4 | 60/1 | |||||||||

| 2004 | 60/2 | 60/3 | 60/4 | |||||||||

| 2005 | 337 | |||||||||||

| 2006 | 338 | 339 | 340 | 341 | 342 | |||||||

| 2007 | 343 | 344 | 345 | 346 | 347 | |||||||

| 2008 | 348 | 349 | 350 | 351 | 352 | |||||||

| Issues of Weird Tales from 2003 to 2008, showing volume and issue numbers. Most issues were titled with either the month or with two months (e.g. "March/April 2004"). One issue, Spring 2003, was titled with the season instead. Editors were Scithers and Schweitzer (yellow); Scithers, Schweitzer and Betancourt (orange); Segal (blue); and Vandermeer (gray).[47] | ||||||||||||

Weird Tales was more lastingly revived at the end of the 1980s by George H. Scithers, John Gregory Betancourt and Darrell Schweitzer, who formed Terminus Publishing, based in Philadelphia, and licensed the rights from Weinberg. Rather than focus on newsstand distribution, which was expensive and had become less effective in the 1980s, they planned to build a base of direct subscribers and distribute the magazine for sale through specialist stores.[58] The first issue had a cover date of Spring 1988, but it was produced early enough to be available at the 1987 World Fantasy Convention in Nashville, Tennessee.[58][59] The size was the same as the original pulp version, though it was printed on better paper. There were also limited edition hardcover versions of each issue, signed by the contributors. A special World Fantasy Award Weird Tales received in 1992 made it apparent that the magazine was successful in terms of quality, but sales were insufficient to cover costs. To save money the format was changed to a larger flat size, starting with the Winter 1992/1993 issue, but the magazine remained in financial trouble, issues becoming irregular over the next couple of years. The Summer 1993 issue was the last to have a hardcover edition; it was also the last, for a while, to bear the name Weird Tales, as Weinberg did not renew the license. The magazine was retitled Worlds of Fantasy & Horror, and the volume numbering was restarted at volume 1 number 1, but in every other way the magazine was unchanged, and the four issues under this title, issued between 1994 and 1996, are regarded by bibliographers as part of the overall Weird Tales run.[58]

In April 1995, HBO announced they had plans to turn Weird Tales into a three-episode anthology show similar to their Tales from the Crypt series. The deal for the rights was facilitated by screenwriters Mark Patrick Carducci and Peter Atkins. Directors Tim Burton, Francis Ford Coppola, and Oliver Stone were executive producers, and each was expected to direct an episode. Stone was to be director of the pilot, but the series never came to fruition.[60]

| Winter | Spring | Summer | Fall | Winter | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 353 | 354 | |||

| 2010 | 355 | 356 | |||

| 2011 | 357 | 358 | nn | ||

| 2012 | 359 | 360 | |||

| 2013 | 361 | ||||

| 2014 | 362 | ||||

| Issues of Weird Tales from 2009 to 2014, showing volume and issue numbers. The issue labelled "nn" was not numbered; it was a preview copy given away at the World Fantasy Convention. Editors were Vandermeer (gray); Segal (blue); and Kaye (mauve).[47] | |||||

No issues appeared in 1997, but in 1998 Scithers and Schweitzer negotiated a deal with Warren Lupine of DNA Publications which allowed them to start publishing Weird Tales under license once again. The first issue was dated Summer 1998, and, other than the omission of the Winter 1998 issue, a regular quarterly schedule was maintained for the next four and a half years. Sales were weak, never rising above 6,000 copies, and DNA began to experience financial difficulties. Wildside Press, owned by John Betancourt, joined DNA and Terminus Publishing as co-publisher, starting with the July/August 2003 issue, and Weird Tales returned to a mostly regular schedule for a few months. A long hiatus ended with the December 2004 issue, which appeared in early 2005; this was the last issue under the arrangement with DNA. Wildside Press then bought Weird Tales, and Betancourt again joined Scithers and Schweitzer as co-editor.[47][58]

The first Wildside Press edition appeared in September 2005, and starting with the following issue, dated February 2006, the magazine was able to stay on a more or less bimonthly schedule for some time. In early 2007, Wildside announced a revamp of Weird Tales, naming Stephen H. Segal the editorial and creative director and later recruiting Ann VanderMeer as the new fiction editor.[51] In January 2010, the magazine announced Segal was leaving the top editorial post to become an editor at Quirk Books. VanderMeer was elevated to editor-in-chief, Mary Robinette Kowal joined the staff as art director and Segal became senior contributing editor.[61]

On August 23, 2011, John Betancourt announced that Wildside Press would be selling Weird Tales to Marvin Kaye and John Harlacher of Nth Dimension Media. Marvin Kaye took over chief editorial duties. Issue 359, the first under the new publishers, was published in late February 2012. Some months before the release of issue 359, a special World Fantasy Convention preview issue was given away for free to interested attendees.[62][63][64][65] Four issues then appeared, with issue #362 published in Spring of 2014.[66]

On August 14, 2019, the official Weird Tales Facebook magazine announced the return of Weird Tales with author Jonathan Maberry as the editorial director. Issue #363-367 (2019-2023) became available to purchase at the Weird Tales website.[67]

Contents and reception

Henneberger gave Weird Tales the subtitle "The Unique Magazine" from the first issue. Henneberger had been hoping for submissions of "off-trail", or unusual, material. He later recalled talking to three well-known Chicago writers, Hamlin Garland, Emerson Hough, and Ben Hecht, each of whom had said they avoided writing stories of "fantasy, the bizarre, and the outré" because of the likelihood of rejection by existing markets.[10] He added "I must confess that the main motive in establishing Weird Tales was to give the writer free rein to express his innermost feelings in a manner befitting great literature",[10] but it is unlikely any of these authors promised to submit anything to Henneberger.[68]

Edwin Baird

Edwin Baird, the first editor of Weird Tales, was not an ideal choice for the job as he disliked horror stories; his expertise was in crime fiction, and most of the material he acquired was bland and unoriginal.[9][10] The writers Henneberger had been hoping to publish, such as Garland and Hough, failed to submit anything to Baird, and the magazine published mostly traditional ghost fiction, many of the stories being narrated by characters in lunatic asylums, or told in diary format.[70][71] The cover story for the first issue was "Ooze", by Anthony M. Rud; there was also the first installment of a serial, "The Thing of A Thousand Shapes", by Otis Adelbert Kline, and 22 other stories. Ashley suggests that the better pulp writers from whom Baird did manage to acquire material, such as Francis Stevens and Austin Hall, were sending Baird stories which had already been rejected elsewhere.[72]

In the middle of the year Baird received five stories submitted by H. P. Lovecraft; Baird bought all five of them. Lovecraft, who had been persuaded by friends to submit the stories, included a cover letter that was so remarkably negative about the quality of the manuscripts that Baird published it in the September 1923 issue, with a note appended saying that he had bought the stories "despite the foregoing, or because of it".[73] Baird insisted that the stories be resubmitted as typed double-spaced manuscripts; Lovecraft disliked typing, and initially decided to resubmit only one story, "Dagon".[73] It appeared in the October 1923 issue, which was the most noteworthy of Baird's tenure, since it included stories by three writers who would become frequent contributors to Weird Tales: as well as Lovecraft, it marked the first appearance in the magazine of Frank Owen and Seabury Quinn.[15][72]

Robert Weinberg, in his history of Weird Tales, agrees with Ashley that the quality of Baird's issues was poor, but comments that some good stories were published: "it was just that the percentage of such stories was dismally small".[71] Weinberg singles out "A Square of Canvas" by Rud, and "Beyond the Door" by Paul Suter as "exceptional";[71] both appeared in the April 1923 issue. Weinberg also regards "The Floor Above" by M. L. Humphries and "Penelope" by Vincent Starrett, both from the May 1923 issue, and "Lucifer" by John Swain, from the November 1923 issue, as memorable, and comments that "The Rats in the Walls", in the March 1924 issue, was one of Lovecraft's finest stories. Baird is also credited with discovering and encouraging Lovecraft.[74][notes 7] It was Henneberger who came up with another idea involving Lovecraft: Henneberger contacted Harry Houdini and made arrangements to have Lovecraft ghost-write a story for him using a plot supplied by Houdini. The story, "Imprisoned with the Pharaohs", appeared under Houdini's name in the May/June/July 1924 issue, though it was nearly lost—Lovecraft left the typed manuscript on the train he took to New York to get married, and as a result spent much of his wedding day retyping the manuscript from the longhand copy he still had.[76][77]

The May/June/July 1924 issue included another story: "The Loved Dead", by C. M. Eddy Jr. which included a mention of necrophilia.[78][79] According to Eddy, this led to the magazine being removed from the newsstands in several cities, and beneficial publicity for the magazine, helping sales, but in his history of Weird Tales Robert Weinberg reports that he found no evidence of the magazine being banned, and the financial state of the magazine implies there was no benefit to sales either.[78] S. T. Joshi, Lovecraft's biographer, contends that the magazine was indeed removed from newsstands in Indiana,[80] but according to John Locke, a magazine historian, the suggestion that there was ever a public reaction to the story is a misinterpretation of comments made by Lovecraft about the story.[81]

The cover art during Baird's tenure was dull; Ashley calls it "unattractive",[9] and Weinberg describes the color scheme of the first issue's cover as "less than inspired", though he considers the next month's cover to be an improvement. He adds that from the May 1923 issue "the covers plunged into a pit of mediocrity". In Weinberg's opinion the poor cover art, frequently by R. M. Mally, was probably partly to blame for the magazine's lack of success under Baird.[69] Weinberg also regards the interior art during the magazine's first year as very weak; most of the interior drawings were small, and with little of the atmosphere one would expect from a horror magazine. All the illustrations were by Heitman, whom Weinberg describes as "... notable for his complete lack of imagination. Heitman's specialty was taking the one scene in a frightening story that featured nothing at all frightening or weird and illustrating that".[82][83]

Farnsworth Wright

The new editor, Farnsworth Wright, was much more willing than Baird had been to publish stories that did not fit into any of the existing pulp categories. Ashley describes Wright as "erratic" in his selections, but under his guidance the magazine steadily improved in quality.[85] His first issue, November 1924, was little better than those edited by Baird, although it included two stories by new writers, Frank Belknap Long and Greye La Spina, who became popular contributors.[86] Over the following year, Wright established a group of writers as regulars, including Long and La Spina, and published many stories by writers who would be closely associated with the magazine for the next decade and more. In April 1925, Nictzin Dyalhis's first story, "When the Green Star Waned", appeared; although Weinberg regards it as very dated, it was highly regarded at the time, Wright listing it in 1933 as the most popular story to appear in Weird Tales. That issue also contained the first instalment of La Spina's novel Invaders from the Dark, which Baird had rejected as "too commonplace". It proved to be extremely popular with readers, and Weinberg comments that Baird's rejection was "just one of the many mistakes made by the earlier editor".[87]

Arthur J. Burks, who would go on to be a very successful pulp writer, appeared under both his real name and under a pseudonym, used for his first sale, in January 1925.[87][88] Robert Spencer Carr's first story appeared in March 1925; H. Warner Munn's "The Werewolf of Ponkert" appeared in July 1925, and in the same issue Wright printed "Spear and Fang", the first professional sale of Robert E. Howard, who would become famous as the creator of Conan the Barbarian.[87] In late 1925 Wright added a "Weird Tales reprint" department, which showcased old weird stories, typically horror classics. Often these were translations, and in some cases the appearance in Weird Tales was the story's first appearance in English.[89]

Wright initially rejected Lovecraft's "The Call of Cthulhu", but eventually bought it, and printed it in the February 1928 issue.[90] This was the first tale of the Cthulhu Mythos, a fictional universe in which Lovecraft set several stories. Over time other writers began to contribute their own stories with the same shared background, including Frank Belknap Long, August Derleth, E. Hoffmann Price, and Donald Wandrei. Robert E. Howard and Clark Ashton Smith were friends of Lovecraft's, but did not contribute Cthulhu stories; instead Howard wrote sword and sorcery fiction, and Smith produced a series of high fantasy stories, many of which were part of his Hyperborean cycle.[85] Robert Bloch, later to become well known as the writer of the movie Psycho, began publishing stories in Weird Tales in 1935; he was a fan of Lovecraft's work, and asked Lovecraft's permission to include Lovecraft as a character in one of his stories, and to kill the character off. Lovecraft gave him permission, and reciprocated by killing off a thinly disguised version of Bloch in one of his own stories not long afterward.[91][notes 8] Edmond Hamilton, a leading early writer of space opera, became a regular, and Wright also published science fiction stories by J. Schlossel and Otis Adelbert Kline.[70] Tennessee Williams' first sale was to Weird Tales, with a short story titled "The Vengeance of Nitocris". This was published in the August 1928 issue under the author's real name, Thomas Lanier Williams.[93]

Weird Tales' subtitle was "The Unique Magazine", and Wright's story selections were as varied as the subtitle promised;[3] he was willing to print strange or bizarre stories with no hint of the fantastic if they were unusual enough to fit in the magazine.[89] Although Wright's editorial standards were broad, and although he personally disliked the restrictions that convention placed on what he could publish, he did exercise caution when presented with material that might offend his readership.[85][94] E. Hoffmann Price records that his story "Stranger from Kurdistan" was held after purchase for six months before Wright printed it in the July 1925 issue; the story includes a scene in which Christ and Satan meet, and Wright was worried about the possible reader reaction. The story nevertheless proved to be very popular, and Wright reprinted it in the December 1929 issue. He also published "The Infidel's Daughter" by Price, a satire of the Ku Klux Klan, which drew an angry letter and a cancelled subscription from a Klan member. Price later recalled Wright's response: "a story that arouses controversy is good for circulation ... and anyway it would be worth a reasonable loss to rap bigots of that caliber".[94] Wright also printed George Fielding Eliot's "The Copper Bowl", a story about a young woman being tortured; she dies when her torturer forces a rat to eat through her body. Weinberg suggests that the story was so gruesome that it would have been difficult to place in a magazine even fifty years later.[95]

On several occasions Wright rejected a story of Lovecraft's only to reconsider later; de Camp suggests that Wright's rejection at the end of 1925 of Lovecraft's "In the Vault", a story about a mutilated corpse taking revenge on the undertaker responsible, was because it was "too gruesome", but Wright changed his mind a few years later, and the story eventually appeared in April 1932.[96] Wright also rejected Lovecraft's "Through the Gates of the Silver Key" in mid-1933. Price had revised the story before passing it to Wright, and after Wright and Price discussed the story, Wright bought it, in November of that year.[97] Wright turned down Lovecraft's novel At the Mountains of Madness in 1935, though in this case it was probably because of the story's length—running a serial required paying an author for material that would not appear until two or three issues later, and Weird Tales often had little cash to spare. In this case he did not change his mind.[98]

Quinn was Weird Tales' most prolific author, with a long-running sequence of stories about a detective, Jules de Grandin, who investigated supernatural events, and for a while he was the most popular writer in the magazine.[notes 9] Other regular contributors included Paul Ernst, David H. Keller, Greye La Spina, Hugh B. Cave, and Frank Owen, who wrote fantasies set in an imaginary version of the Far East.[85] C.L. Moore's story "Shambleau", her first sale, appeared in Weird Tales in November 1933; Price visited the Weird Tales offices shortly after Wright read the manuscript for it, and recalls that Wright was so enthusiastic about the story that he closed the office, declaring it "C.L. Moore day".[100] The story was very well received by readers, and Moore's work, including her stories about Jirel of Joiry and Northwest Smith, appeared almost exclusively in Weird Tales over the next three years.[85][101]

As well as fiction, Wright printed a substantial amount of poetry, with at least one poem included in most issues. Originally this often included reprints of poems such as Edgar Allan Poe's "El Dorado", but soon most of the poetry was original, with contributions from Lovecraft, Howard, and Clark Ashton Smith, among many others.[102][103][104] Lovecraft's contributions included ten of his "Fungi from Yuggoth" poems, a series of sonnets on weird themes that he wrote in 1930.[105]

The artwork was an important element of the magazine's personality; Margaret Brundage, who painted many covers featuring nudes for Weird Tales, was perhaps the best known artist.[85] Many of Brundage's covers were for stories by Seabury Quinn, and Brundage later commented that once Quinn realized that Wright always commissioned covers from Brundage that included a nude, "he made sure that each de Grandin story had at least one sequence where the heroine shed all her clothes".[106] For over three years in the early 1930s, from June 1933 to August/September 1936, Brundage was the only cover artist Weird Tales used.[106][107] Another prominent cover artist was J. Allen St. John, whose covers were more action-oriented, and who designed the title logo used from 1933 until 2007.[85] Hannes Bok's first professional sale was to Weird Tales, for the cover of the December 1939 issue; he became a frequent contributor over the next few years.[108]

Virgil Finlay, one of the most important figures in the history of science fiction and fantasy art, made his first sale to Wright in 1935; Wright only bought one interior illustration from Finlay at that time because he was concerned that Finlay's delicate technique would not reproduce well on pulp paper. After a test print on pulp stock demonstrated that the reproduction was more than adequate,[109] Wright began to buy regularly from Finlay, who became a regular cover artist for Weird Tales starting with the December 1935 issue.[110] Demand from readers for Finlay's artwork was so high that in 1938 Wright commissioned a series of illustrations from Finlay for lines taken from famous poems, such as "O sweet and far, from cliff and scar/The horns of Elfland faintly blowing", from Tennyson's "The Princess".[111] Not every artist was as successful as Brundage and Finlay: Price suggested that Curtis Senf, who painted 45 covers early in Wright's tenure, "was one of Sprenger's bargains", meaning that he produced poor art, but worked fast for low rates.[112]

During the 1930s, Brundage's rate for a cover painting was $90. Finlay received $100 for his first cover, which appeared in 1937, over a year after his first interior illustrations were used; Weinberg suggests that the higher fee was partly to cover postage, since Brundage lived in Chicago and delivered her artwork in person, but it was also because Brundage's popularity was beginning to decline. When Delaney acquired the magazine in late 1938, the fee for a cover painting was cut to $50, and in Weinberg's opinion the quality of the artwork declined immediately. Nudes no longer appeared, though it is not known if this was a deliberate policy on Delaney's part. In 1939 a campaign by Fiorello LaGuardia, the mayor of New York, to eliminate sex from the pulps led to milder covers, and this may also have had an effect.[113]

In 1936, Howard committed suicide, and the following year Lovecraft died.[114] There was so much unpublished work by Lovecraft[notes 10] that Wright was able to use that he printed more material under Lovecraft's byline after his death than before.[115] In Howard's case, there was no such trove of stories available, but other writers such as Henry Kuttner provided similar material.[35] By the end of Wright's tenure as editor, many of the writers who had become strongly associated with the magazine were gone; Kuttner, and others such as Price and Moore, were still writing, but Weird Tales' rates were too low to attract submissions from them. Clark Ashton Smith had stopped writing, and two other writers who were well-liked, G.G. Pendarves and Henry Whitehead, had died.[114]

Except for a couple of short-lived magazines such as Strange Tales and Tales of Magic and Mystery, and a weak challenge from Ghost Stories, all between the late 1920s and the early 1930s, Weird Tales had little competition for most of Wright's sixteen years as editor. In the early 1930s, a series of pulp magazines began to appear that became known as "weird menace" magazines. These lasted until the end of the decade, but despite the name there was little overlap in subject matter between them and Weird Tales: the stories in the weird menace magazines appeared to be based on occult or supernatural events, but at the end of the tale the mystery was always revealed to have a logical explanation.[116] In 1935 Wright began running weird detective stories to try to attract some of the readers of these magazines to Weird Tales, and asked readers to write in with comments. Reader reaction was uniformly negative, and after a year he announced that there would be no more of them.[117]

In 1939 two more serious threats appeared, both launched to compete directly for Weird Tales' readers. Strange Stories appeared in February 1939 and lasted for just over two years; Weinberg describes it as "top-quality",[114] though Ashley is less complimentary, describing it as largely unoriginal and imitative.[118] The following month the first issue of Unknown appeared from Street & Smith.[119] Fritz Leiber submitted several of his "Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser" stories to Wright, but Wright rejected all of them (as did McIlwraith when she took over the editorship). Leiber subsequently sold them all to John W. Campbell for Unknown; Campbell commented each time to Leiber that "these would be better in Weird Tales". The stories grew into a very popular sword and sorcery series, but none of them ever appeared in Weird Tales. Leiber did eventually sell several stories to Weird Tales, beginning with "The Automatic Pistol", which appeared in May 1940.[114][120]

Weird Tales included a letters column, titled "The Eyrie", for most of its existence, and during Wright's time as editor it was usually filled with long and detailed letters. When Brundage's nude covers appeared, a lengthy debate over whether they were suitable for the magazine was fought out in the Eyrie, the two sides being divided about equally. For years it was the most discussed topic in the magazine's letter column. Many of the authors Wright published wrote letters too, including Lovecraft, Howard, Kuttner, Bloch, Smith, Quinn, Wellman, Price, and Wandrei. In most cases these letters praised the magazine, but occasionally a critical comment was raised, as when Bloch repeatedly expressed his dislike for Howard's stories of Conan the Barbarian, referring to him as "Conan the Cimmerian Chipmunk".[121] Another debate that was aired in the letter column was the question of how much science fiction the magazine should include. Until Amazing Stories was launched in April 1926, science fiction was popular with Weird Tales' readers, but after that point letters began to appear asking Wright to exclude science fiction, and only publish weird fantasy and horror. The pro-science fiction readers were in the majority, and as Wright agreed with them, he continued to include science fiction in Weird Tales.[122] Hugh B. Cave, who sold half-a-dozen stories to Wright in the early 1930s, commented on "The Eyrie" in a letter to a fellow writer: "No other magazine makes such a point of discussing past stories, and letting the authors know how their stuff is received".[123]

Dorothy McIlwraith

McIlwraith was an experienced magazine editor, but she knew little about weird fiction, and unlike Wright she also had to face real competition from other magazines for Weird Tales' core readership.[114] Although Unknown folded in 1943, in its four years of existence it transformed the field of fantasy and horror, and Weird Tales was no longer regarded as the leader in its field. Unknown published many successful humorous fantasy stories, and McIlwraith responded by including some humorous material, but Weird Tales' rates were less than Unknown's, with predictable effects on quality.[35][119] In 1940 the policy of reprinting horror and weird classics ceased, and Weird Tales began using the slogan "All Stories New – No Reprints". Weinberg suggests that this was a mistake, as Weird Tales' readership appreciated getting access to classic stories "often mentioned but rarely found".[125] Without the reprints Weird Tales was left to survive on the rejects from Unknown, the same authors selling to both markets. In Weinberg's words, "only the quality of the stories [separated] their work between the two pulps".[125]

Delaney's personal taste also reduced McIlwraith's latitude. In an interview with Robert A. Lowndes in early 1940, Delaney spoke about his plans for Weird Tales. After saying that the magazine would still publish "all types of weird and fantasy fiction", Lowndes reported that Delaney did not want "stories which center about sheer repulsiveness, stories which leave an impression not to be described by any other word than 'nasty'". Lowndes later added that Delaney had told him he found some of Clark Ashton Smith's stories on the "disgusting side".[126][notes 11]

McIlwraith continued to publish many of Weird Tales' most popular authors, including Quinn, Derleth, Hamilton, Bloch, and Manly Wade Wellman.[35] She also added new contributors, including Ray Bradbury. Weird Tales regularly featured Fredric Brown, Mary Elizabeth Counselman, Fritz Leiber, and Theodore Sturgeon.[85] As Wright had done, McIlwraith continued to buy Lovecraft stories submitted by August Derleth, though she abridged some of the longer pieces, such as "The Shadow over Innsmouth".[115] Sword and sorcery stories, a genre which Howard had made much more popular with his stories of Conan, Solomon Kane and Bran Mak Morn in Weird Tales in the early 1930s, had continued to appear under Farnsworth Wright; they all but disappeared during McIlwraith's tenure. McIlwraith also focused more on short fiction, and serials and long stories were rare.[35][127]

In May 1951 Weird Tales once again began to include reprints, in an attempt to reduce costs, but by that time the earlier issues of Weird Tales had been extensively mined for reprints by August Derleth's publishing venture, Arkham House, and as a result McIlwraith often reprinted lesser-known stories. They were not advertised as reprints, which led in a couple of cases to letters from readers asking for more stories from H. P. Lovecraft, whom they believed to be a new author.[128]

In Weinberg's opinion, the magazine lost variety under McIlwraith's editorship, and "much of the uniqueness of the magazine was gone".[35] In Ashley's view, the magazine became more consistent in quality, rather than worse; Ashley comments that though the issues edited by McIlwraith "seldom attain[ed] Wright's highpoints, they also omitted the lows".[85] L. Sprague de Camp, toward the end of McIlwraith's time as editor, agreed that the 1930s were the magazine's heyday, citing Wright's death and the departure for other, better-paying, markets of several of its contributors as factors in the magazine's decline.[129]

The quality of Weird Tales' artwork suffered when Delaney cut the rates.[130] Bok, whose first cover had appeared in December 1939, moved to New York and joined the office art staff for a while; he eventually left because of the low pay. Boris Dolgov began contributing in the 1940s; he was a friend of Bok's and the two occasionally collaborated, signing the result "Dolbokgov". Weinberg regards Dolgov's illustration for Robert Bloch's "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper" as one of his best works.[131] Weird Tales' paper was of very poor quality, which meant that the reproductions were poor, and along with the low pay rate for art this meant that many artists treated Weird Tales as a last resort for their work.[132] Damon Knight, who sold some interior artwork to Weird Tales in the early 1940s, recalled later that he was paid $5 for a single-page drawing, and $10 for a double-page spread; he worked slowly and the low pay meant Weird Tales was not a viable market for him.[133]

The art editor, Lamont Buchanan, was able to establish five artists as regulars by the mid-1940s; they remained regular contributors until 1954, when the magazine's first incarnation ceased publication. The five were Dolgov, John Giunta, Fred Humiston, Vincent Napoli, and Lee Brown Coye.[132] In Weinberg's review of Weird Tales' interior art, he describes Humiston's work as ranging "from bad to terrible", but he is more positive about the others. Napoli had worked for Weird Tales from 1932 to the mid-1930s, when he began selling to the science fiction pulps, but his work for Short Stories brought him back to Weird Tales in the 1940s. Weinberg speaks highly of both Napoli and Coye, whom Weinberg describes as "the master of the weird and grotesque illustration". Coye did a series of full-page illustrations for Weird Tales called "Weirdisms", which ran intermittently from November 1948 to July 1951.[134][135][136]

The letter column, "The Eyrie", was much reduced in size during McIlwraith's tenure, but as a gesture to the readers a "Weird Tales Club" was started. Joining the Club simply meant writing in to receive a free membership card; the only other benefit was that the magazine listed all the members' names and addresses, so that members could contact each other. Among the names listed in the January 1943 issue was that of Hugh Hefner, later to become famous as the founder of Playboy.[137]

Toward the end of McIlwraith's time as editor a couple of new writers appeared, including Richard Matheson and Joseph Payne Brennan.[85] Brennan had already sold over a dozen stories to other pulps when he finally made a sale to McIlwraith, but he had always wanted to sell to Weird Tales, and three years after the magazine folded he launched a small-press horror magazine named Macabre, which he published for some years, in imitation of Weird Tales.[138]

Moskowitz, Carter, and Bellerophon

The four issues edited by Sam Moskowitz in the early 1970s included a detailed biography of William Hope Hodgson, serialized over three issues, along with some rare stories of Hodgson's that Moskowitz had unearthed. Many of the other stories were reprints, either from Weird Tales or from other early pulps such as The Black Cat or Blue Book. In Ashley's opinion, the magazine "had the feel of a museum piece with nothing new or progressive", though Weinberg describes the magazine as having "an interesting jumble of contents".[139] The subsequent paperback series edited by Lin Carter was criticized in similar terms: Weinberg regards it as having "too much reliance ... on the old names like Lovecraft, Howard and Smith by reprinting mediocre material ... New writers were not sufficiently encouraged",[139] though Weinberg does add that Ramsey Campbell, Tanith Lee and Steve Rasnic Tem were among the newer writers who contributed good material.[139] Ashley's opinion of the two Bellerophon issues is low: he describes them as lacking "any clear editorial direction or acumen".[56]

Ann VanderMeer

The April/May 2007 edition featured the magazine's first all-new design in almost seventy-five years. With Stephen H. Segal as editorial and creative director and Ann VanderMeer as fiction editor,[51] during the next few years the magazine "won a number of awards and great acclaim."[140] In 2010 VanderMeer became the magazine's editor-in chief.[51][141]

During this time Weird Tales published works by a wide range of strange-fiction authors including Michael Moorcock and Tanith Lee, as well as newer writers such as N. K. Jemisin, Jay Lake, Cat Rambo, and Rachel Swirsky.[51] This period also saw the addition of a broader range of content, ranging from narrative essays to comics to features on weird culture. The magazine won its first Hugo Award in August 2009, in the semiprozine category,[142] along with receiving two Hugo Award nominations in subsequent years[143] and its first World Fantasy Award nomination, for Segal and Vandermeer, in more than seventeen years.[143][144]

In addition to winning or being nominated for awards, under VanderMeer's editorship Weird Tales saw the number of subscriptions triple as the magazine "came to symbolise what was good about the changes in the SF community."[145]

Marvin Kaye and after

in 2011 Marvin Kaye and John Harlacher purchased Weird Tales from John Gregory Betancourt[146] with Kaye taking over chief editorial duties from VanderMeer. Issue 359, the first under the new publishers, was published in late February 2012. Some months before the release of issue 359, a special World Fantasy Convention preview issue was given away for free to interested attendees.[62]

In August 2012, Weird Tales became involved in a media altercation after Kaye announced the magazine was going to publish an excerpt from Victoria Foyt's controversial novel Save the Pearls, which many critics accused of featuring racist stereotyping. The decision was made despite the protests of VanderMeer, and prompted her to end her association with the magazine.[147] Kaye wrote an essay titled "A Thoroughly NONRACIST Novel" defending his decision to publish the excerpt.[146] Both the essay and Kaye's decision to publish the excerpt were heavily criticized, N. K. Jemisin saying "This is how you destroy something beautiful" with regards to the magazine[148] and Jim C. Hines saying he was "highly disturbed that the editor ever thought this was in any way a good idea, that he was so supportive of this novel that he was going out of his way to defend and support it … up until the Internet landed on his head."[149]

The publisher subsequently overruled Kaye and announced that Weird Tales no longer had plans to run the excerpt.[150]

After the fall 2012 issue #360, Kaye only published two more issues of Weird Tales, issue #361 in the summer of 2013 and #362 in the spring of 2014.[151]

In 2019 Weird Tales returned with author Jonathan Maberry as the editorial director, with issue #363 being released at the end of that year.[152] This issue featured the story "Up from Slavery" by Victor LaValle, which later won the Stoker Award for Best Long Fiction.[153][154]

Legacy

Weird Tales was one of the most important magazines in the fantasy field; in Ashley's view, it is "second only to Unknown in significance and influence".[3] Weinberg goes further, calling it "the most important and influential of all fantasy magazines". Weinberg argues that much of the material Weird Tales published would never have appeared if the magazine had not existed. It was through Weird Tales that Lovecraft, Howard, and Clark Ashton Smith became widely known, and it was the first and one of the most important markets for weird and science fantasy artwork. Many of the horror stories adapted for early radio shows such as Stay Tuned for Terror originally appeared in Weird Tales.[2] The magazine's "Golden Age" was under Wright, and de Camp argues that one of Wright's accomplishments was to create a "Weird Tales school of writing".[155] Justin Everett and Jeffrey H. Shanks, the editors of a recent scholarly collection of literary criticism focused on the magazine, argue that "Weird Tales functioned as a nexus point in the development of speculative fiction from which emerged the modern genres of fantasy and horror".[156]

The magazine was, unusually for a pulp, included by the editors of the annual Year in Fiction anthologies, and was generally regarded with more respect than most of the pulps. This remained true long after the magazine's first run ended, as it became the main source of fantasy short stories for anthologists for several decades.[157] Weinberg argues that the fantasy pulps, of which, in his opinion, Weird Tales was the most influential, helped to form the modern fantasy genre, and that Wright, "if he was not a perfect editor ... was an extraordinary one, and one of the most influential figures in modern American fantasy fiction",[158] adding that Weird Tales and its competitors "served as the bedrock upon which much of modern fantasy rests".[159] Everett and Shanks agree, and regard Weird Tales as the venue where writers, editors and an engaged readership "elevated speculated fiction to new heights" with influence that "reverberates through modern popular culture".[160] In Ashley's words, "somewhere in the imagination reservoir of all U.S. (and many non-U.S.) genre-fantasy and horror writers is part of the spirit of Weird Tales".[4]

Bibliographic details

The editorial succession at Weird Tales was as follows:[11][162]

| Editor | Issues |

|---|---|

| Edwin Baird | March 1923 – May/June/July 1924 |

| Farnsworth Wright | November 1924 – March 1940 |

| Dorothy McIlwraith | May 1940 – September 1954 |

| Sam Moskowitz | April 1973 – Summer 1974 |

| Lin Carter | Spring 1981 – Summer 1983 |

| Forrest J Ackerman/Gil Lamont | Fall 1984 |

| Gordon Garb | Winter 1985 |

| Darrell Schweitzer | Spring 1988 – Winter 1990

September 2005 – February/March 2007 |

| Darrell Schweitzer | Spring 1991 – Winter 1996/1997 |

| Darrell Schweitzer

George Scithers |

Summer 1998 – December 2004 |

| Stephen Segal | April/May 2007 – September/October 2007

Spring 2010 |

| Ann VanderMeer | November/December 2007 – Fall 2009

Summer 2010 – Winter 2012 |

| Marvin Kaye | Fall 2012 – Spring 2014 |

| Jonathan Maberry | Summer 2019 – present |

Baird was listed as editor for the May/June/July 1924 issue, but that issue was assembled by Wright and Kline.[12]

The publisher for the first year was Rural Publishing Corporation; this changed to Popular Fiction Publishing with the November 1924 issue, and to Weird Tales, Inc. with the December 1938 issue. The four issues in the early 1970s came from Renown Publications, and the four paperbacks in the early 1980s were published by Zebra Books. The next two issues were from Bellerophon, and then from Spring 1988 to Winter 1996 the publisher was Terminus. From Summer 1998 to July/August 2003 the publisher was DNA Publications and Terminus, listed either as DNA Publications/Terminus or just as DNA Publications. The September/October 2003 issue listed the publisher as DNA Publications/Wildside Press/Terminus, and through 2004 this remained the case, one issue dropping Terminus from the masthead. Thereafter Wildside Press was the publisher, sometimes with Terminus listed as well, until the September/October 2007 issue, after which only Wildside Press were listed. The issues published from 2012 through 2014 were from Nth Dimension Media.[11][162]

Weird Tales was in pulp format for its entire first run except for the issues from May 1923 to April 1924, when it was a large pulp, and the last year, from September 1953 to September 1954, when it was a digest. The four 1970s issues were in pulp format. The two Bellerophon issues were quarto. The Terminus issues reverted to pulp format until the Winter 1992/1993 issue, which was large pulp. A single pulp issue appeared in Fall 1998, and then the format returned to large pulp until the Fall 2000 issue, which was quarto. The format varied between large pulp and quarto until January 2006, which was large pulp, as were all issues after that date until Fall 2009, except for a quarto-sized November 2008. From Summer 2010 the format was quarto.[11][162]

The first run of the magazine was priced at 25 cents for the first fifteen years of its life except for the oversized May/June/July 1924 issue, which was 50 cents. In September 1939 the price was reduced to 15 cents, where it stayed until the September 1947 issue, which was 20 cents. The price went up again to 25 cents in May 1949; the digest-sized issues from September 1953 to September 1954 were 35 cents. The first three paperbacks edited by Lin Carter were priced at $2.50; the fourth was $2.95. The two Bellerophon issues were $2.50 and $2.95. The Terminus Weird Tales began in Spring 1988 priced at $3.50; this went up to $4.00 with the Fall 1988 issue, and to $4.95 with the Summer 1990 issue. The next price increase was to $5.95, in Spring 2003, and then to $6.99 with the January 2008 issue. The first two issues from Nth Dimension Media were priced at $7.95 and $6.99; the last two were $9.99 each.[11][162]

Some of the early Terminus editions of Weird Tales were also printed in hardcover format, in limited editions of 200 copies. These were signed by the contributors, and were available at $40 as part of a subscription offer. Issues produced in this format include Summer 1988, Spring/Fall 1989, Winter 1989/1990, Spring 1991, and Winter 1991/1992.[58][162]

Anthologies

Starting in 1925, Christine Campbell Thomson edited a series of horror story anthologies, published by Selwyn and Blount, titled Not at Night. These were considered an unofficial U.K. edition of the magazine, the stories sometimes appearing in the anthology before the magazine's U.S. version appeared. The ones which drew a substantial fraction of their contents from Weird Tales were:[163][164]

| Year | Title | Stories from Weird Tales |

|---|---|---|

| 1925 | Not at Night | All 15 |

| 1926 | More Not at Night | All 15 |

| 1927 | You'll Need a Night Light | 14 of 15 |

| 1929 | By Daylight Only | 15 of 20 |

| 1931 | Switch on the Light | 8 of 15 |

| 1931 | At Dead of Night | 8 of 15 |

| 1932 | Grim Death | 7 of 15 |

| 1933 | Keep on the Light | 7 of 15 |

| 1934 | Terror by Night | 9 of 15 |

There was also a 1937 anthology titled Not at Night Omnibus, which selected 35 stories from the Not at Night series, of which 20 had originally appeared in Weird Tales. In the U.S. an anthology titled Not at Night!, edited by Herbert Asbury, appeared from Macy-Macius in 1928; this selected 25 stories from the series, 24 of them drawn from Weird Tales.[163]

Numerous other anthologies of stories from Weird Tales have been published, including:[51][165][166][167][168][169][170][171][172][173][174][175][176]

| Year | Title | Editor | Publisher | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | The Unexpected | Leo Margulies | Pyramid | |

| 1961 | The Ghoul Keepers | Leo Margulies | Pyramid | |

| 1964 | Weird Tales | Leo Margulies | Pyramid | Ghost edited by Sam Moskowitz |

| 1965 | Worlds of Weird | Leo Margulies | Pyramid | Ghost edited by Sam Moskowitz |

| 1976 | Weird Tales | Peter Haining | Neville Spearman | The hardback edition (but not the paperback) reproduces the original stories in facsimile[177] |

| 1977 | Weird Legacies | Mike Ashley | Star | |

| 1988 | Weird Tales: The Magazine That Never Dies | Marvin Kaye | Nelson Doubleday | |

| 1988 | Weird Tales: 32 Unearthed Terrors | Stefan Dziemianowicz, Martin H. Greenberg & Robert Weinberg | Bonanza Books | |

| 1995 | The Best of Weird Tales | John Betancourt | Barnes & Noble | |

| 1997 | The Best of Weird Tales: 1923 | Marvin Kaye & John Betancourt | Bleak House | |

| 1997 | Weird Tales: Seven Decades of Terror | John Betancourt & Robert Weinberg | Barnes & Noble | |

| 2020 | The Women of Weird Tales | Melanie Anderson | Valancourt Books | |

| 2023 | Weird Tales: 100 Years of Weird | Jonathan Maberry | Weird Tales Presents & Blackstone Publishing |

Canadian and British editions

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | 36/3 | 36/4 | 37/1 | 37/1 | ||||||||

| 1943 | 36/7 | 36/8 | 36/9 | 36/10 | 37/11 | 36/12 | ||||||

| 1944 | 36/13 | 36/14 | 36/15 | 36/15 | 37/5 | 37/6 | ||||||

| 1945 | 38/1 | 38/3 | 38/3 | 38/3 | 38/3 | 38/3 | ||||||

| 1946 | 38/3 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | ||||||

| 1947 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | ||||||

| 1948 | nn | 40/3 | 40/4 | 40/5 | 40/6 | 41/1 | ||||||

| 1949 | 41/2 | 41/3 | 41/4 | 41/5 | 41/6 | 42/1 | ||||||

| 1950 | 42/2 | 42/3 | 42/4 | 42/5 | 42/6 | 43/1 | ||||||

| 1951 | 43/2 | 43/3 | 43/4 | 43/5 | 43/6 | 44/1 | ||||||

| Canadian issues of Weird Tales from 1941 to 1954, showing volume/issue number. "nn" indicates that that issue had no number. The numerous oddities in volume numbering are correctly shown.[178] | ||||||||||||

A Canadian edition of Weird Tales appeared from June 1935 to July 1936; all fourteen issues are thought to be identical to the U.S. issues of those dates, though "Printed in Canada" appeared on the cover, and in at least one case another text box was placed on the cover to conceal part of a nude figure. Another Canadian series began in 1942, as a result of import restrictions placed on U.S. magazines. Canadian editions from 1942 up to January 1948 were not identical to the U.S. editions, but they match closely enough that the originals are easily identified. From the May 1942 to January 1945 issues, they correspond to the U.S. editions two issues earlier, that is, from January 1942 to September 1944. There was no Canadian issue corresponding to the November 1944 U.S. issue, so from that point the Canadian issues were only one behind the U.S. ones: the issues from March 1945 to January 1948 correspond to the U.S. issues from January 1945 to November 1947. There was no Canadian issue of the January 1948 U.S. issue, and from the next issue, March 1948, till the end of the Canadian run in November 1951, the issues were identical to the U.S. versions.[179]

There were numerous differences between the Canadian issues from May 1942 to January 1948 and the corresponding U.S. issues. All the covers were repainted by Canadian artists until the January 1945 issue; thereafter the artwork from the original issues was used. Initially the fiction content of the Canadian issues was unchanged from the U.S., but starting in September 1942 the Canadian Weird Tales dropped some of the original stories in each issue, replacing them with either stories from other issues of Weird Tales, or, occasionally, material from Short Stories.[179]

In a couple of instances a story appeared in the Canadian edition of the magazine before its appearance in the U.S. version, or simultaneously with it, so it is evident that whoever assembled the issues had access to the Weird Tales pending story file. Because of the reorganization of material, it often happened that one of the Canadian issues would have more than a single story by the same author. In these cases a pseudonym was invented for one of the stories.[179]

There were four separate editions of Weird Tales distributed in the United Kingdom. In early 1942, three issues abridged from the September 1940, November 1940, and January 1941 U.S. issues were published in the U.K. by Gerald Swan; they were undated, and had no volume numbers. The middle issue was 64 pages long; the other two were 48 pages. All were priced at 6d. A single issue was released in late 1946 by William Merrett; it also was undated and unnumbered. It was 36 pages long, and was priced at 1/6. The three stories included came from the October 1937 U.S. issue.[177]

A longer run of 23 issues appeared between November 1949 and December 1953, from Thorpe & Porter. These were all undated; the first issue had no volume or issue number but subsequent issues were numbered sequentially. Most were priced at 1/-; issues 11 to 15 were 1/6. All were 96 pages long. The first issue corresponds to the July 1949 U.S. issue; the next 20 issues correspond to the U.S. issues from November 1949 to January 1953, and the final two issues correspond to May 1953 and March 1953, in that order. Another five bimonthly issues appeared from Thorpe & Porter dated November 1953 to July 1954, with the volume numbering restarted at volume 1 number 1. These correspond to the U.S. issues from September 1953 to May 1954.[177]

Collectability

Weird Tales is widely collected, and many issues command very high prices. In 2008, Mike Ashley estimated the first issue to be worth £3,000 in excellent condition, and added that the second issue is much rarer and commands higher prices. Issues with stories by Lovecraft or Howard are very highly sought-after, with the October 1923 issue, containing "Dagon", Lovecraft's first appearance in Weird Tales, fetching comparable prices to the first two issues.[181] The first few volumes are so rare that very few academic collections have more than a handful of these issues: Eastern New Mexico University, the holder of a remarkably complete early science fiction archive, has "only a few scattered issues" from the early years, and the librarian recorded in 1983 that "dealers laugh when Eastern enquires about these".[182]

Prices of the magazine drop over the succeeding decades, the McIlwraith issues being worth far less than the ones edited by Wright. Ashley quotes the digest-sized issues from the end of McIlwraith's tenure as fetching £8 to £10 each as of 2008. The revived editions are not particularly scarce, with two exceptions. The two Bellerophon issues received such poor distribution that they fetch high prices: Ashley quotes a 2008 price of £40 to £50 for the first one, and twice that for the second one. The other valuable recent issues are the hardback versions of the Terminus Weird Tales; Ashley gives prices of between £40 and £90, with some of the special author issues fetching a premium.[181]

Notes

- ^ Lin Carter gives the debt as $41,000, and adds that the original capital was "reputedly" $11,000, meaning that during Baird's tenure the magazine had lost $52,000.[15] L. Sprague de Camp quotes Henneberger's debt as "at least $43,000, and perhaps as much as $60,000".[16] John Locke, in The Thing's Incredible!, his history of the first two years of Weird Tales, reports $51,000 as the debt owed by Rural Publishing in January 1924, rather than just incurred by Weird Tales, and suggests that $60,000 - the number comes from a letter from Wright in the July 1924 issue of The Author & Journalist -- also represents Rural's total indebtedness, in the summer of 1924.[17]

- ^ Henneberger later recalled that Cornelius was in a position to ensure that the debt was never paid off, so that they retained control.[17]

- ^ In the same letter to Long, the 34-year-old Lovecraft, who often affected the airs of an aged gentleman, declared "think of the tragedy of such a move for an aged antiquarian".[22][24]

- ^ Jack Williamson recalls that Weird Tales was paying one cent per word, "rather more reliably" than Amazing Stories, in about 1931;[28] and Hugh Cave quotes one cent per word as the rate in early 1933.[29]

- ^ Histories of the magazine differ as to whether he was fired because of poor sales, or quit because of his health. Ashley says Wright's health made it "impossible to continue", but Weinberg says Delaney let Wright go "in a move to further cut costs". However, in a later history of the magazine, Weinberg says that Wright, "who had been in bad health for many years, stepped down as editor", and does not give any other reason for his departure.[35][37][41]

- ^ Delaney had attempted to revive Short Stories in 1956, but had only produced five issues; Margulies also tried to bring Short Stories back, and kept it alive from December 1957 until August 1959.[48][49][50]

- ^ Henneberger later claimed that he overrode Baird and that Baird did not like Lovecraft's writing.[75]

- ^ Bloch's story was "The Shambler From the Stars", which appeared in the September 1935 issue; Lovecraft's riposte was "The Haunter of the Dark", in December 1936.[91][92]