Geography of Middle-earth

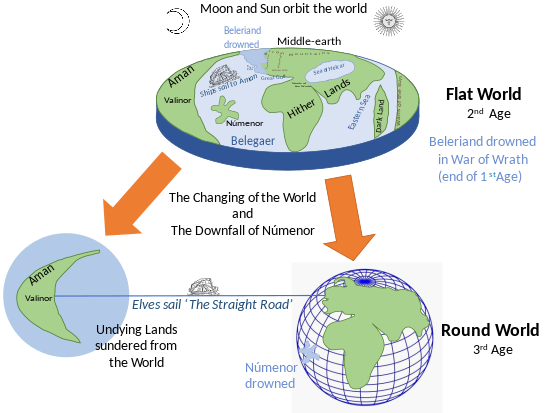

The geography of Middle-earth encompasses the physical, political, and moral geography of J. R. R. Tolkien's fictional continent Middle-earth on the planet Arda, but widely taken to mean all of creation (Eä) as well as all of his writings about it.[1] Arda was created as a flat world, incorporating a Western continent, Aman, which became the home of the godlike Valar, as well as Middle-earth. At the end of the First Age, the Western part of Middle-earth, Beleriand, was drowned in the War of Wrath. In the Second Age, a large island, Númenor, was created in the Great Sea, Belegaer, between Aman and Middle-earth; it was destroyed in a cataclysm near the end of the Second Age, in which Arda was remade as a spherical world, and Aman was removed so that Men could not reach it.

In The Lord of the Rings, Middle-earth at the end of the Third Age is described as having free peoples, namely Men, Hobbits, Elves, and Dwarves in the West, opposed to peoples under the control of the Dark Lord Sauron in the East. Some commentators have seen this as implying a moral geography of Middle-earth. Tolkien scholars have traced many features of Middle-earth to literary sources such as Beowulf, the Poetic Edda, or the mythical Myrkviðr. They have in addition suggested real-world places such as Venice, Rome, and Constantinople/Byzantium as analogues of places in Middle-earth. The cartographer Karen Wynn Fonstad has created detailed thematic maps for Tolkien's major Middle-earth books, The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and The Silmarillion.

Cosmology

Tolkien's Middle-earth was part of his created world of Arda. It was a flat world surrounded by ocean. It included the Undying Lands of Aman and Eressëa, which were all part of the wider creation, Eä. Aman and Middle-earth were separated from each other by the Great Sea Belegaer, analogous to the Atlantic Ocean. The western continent, Aman, was the home of the Valar, and the Elves called the Eldar.[T 1][1] Initially, the western part of Middle-earth was the subcontinent Beleriand; it was engulfed by the ocean at the end of the First Age.[1] Ossë, on behalf of the Valar, then raised the island continent of Númenor as a gift to the now homeless Men of Beleriand, thenceforth called Númenóreans.

After Eru Ilúvatar destroyed Númenor near the end of the Second Age, he remade Arda as a round world, and the Undying Lands were removed from Arda so that Men could not reach them. The Elves could go there only by the Straight Road and in ships capable of passing out of the sphere of the earth. Tolkien then equated Arda, consisting of both Middle-earth's planet and the heavenly Aman, with the Solar System, the Sun and Moon being celestial objects in their own right, no longer orbiting the Earth.[1][3]

Physical geography

Beleriand, Lindon

The extreme west of Middle-earth in the First Age was Beleriand. It and Eriador were separated from much of the south of Middle-earth by the Great Gulf. Beleriand was largely destroyed in the cataclysm of the War of Wrath, leaving only a remnant coastal plain, Lindon, just to the west of the Ered Luin (also called Ered Lindon or Blue Mountains). The cataclysm divided Ered Luin and Lindon by the newly created Gulf of Lune; the northern part was Forlindon, the southern Harlindon.[4]

Eriador

In the northwest of Middle-earth, Eriador was the region between the Ered Luin and the Misty Mountains. Early in the Third Age, the northern kingdom of Arnor founded by Elendil occupied a large part of the region. After its collapse, much of Eriador became wild; regions such as Minhiriath, on the coast south of the River Baranduin (Brandywine), were abandoned. A small part of the region was occupied by Hobbits to form the Shire. To the northwest lay Lake Evendim, once called Nenuial by the Elves. A remnant of the ancient forest of Eriador survived throughout the Third Age just to the east of the Shire as the Old Forest, the domain of Tom Bombadil.[T 2] Northeast of there is Bree, the only place where hobbits and Men live in the same villages. Further east from Bree is the hill of Weathertop with the ancient fortress of Amon Sûl, and then Rivendell, the home of Elrond. South from there is the ancient land of Hollin, once the elvish land of Eregion, where the Rings of Power were forged. At the Grey Havens (Mithlond), on the Gulf of Lune, Círdan built the ships in which the Elves departed from Middle-earth to Valinor.[T 3][5]

Misty Mountains

The Misty Mountains were thrown up by the Dark Lord Melkor in the First Age to impede Oromë, one of the Valar, who often rode across Middle-earth hunting.[T 4] The Dwarf-realm of Moria was built in the First Age beneath the midpoint of the mountain range. The two major passes across the mountains were the High Pass or Pass of Imladris near Rivendell, with a higher and a lower route,[T 5][T 6] and the all-year Redhorn Pass further south near Moria.[6]

Rhovanion

East of the Misty Mountains, Anduin, the Great River, flows southwards, with the forest of Mirkwood to its east. On its west bank opposite the southern end of Mirkwood is the Elvish land of Lothlorien. Further south, backing on to the Misty Mountains, lies the forest of Fangorn, home of the tree-giants, the ents. In a valley at the southern end of the Misty Mountains is Isengard, home to the wizard Saruman.[7]

Lands to the South

Just to the South of both Fangorn and Isengard is the wide grassy land of the Riders of Rohan, who provide cavalry to its southerly neighbour, Gondor. The River Anduin passes the hills of Emyn Muil and the enormous rock statues of the Argonath and flows through the dangerous rapids of Sarn Gebir and over the Falls of Rauros into Gondor. Gondor's border with Rohan is the Ered Nimrais, the White Mountains, which run east–west from the sea to a point near the Anduin; at that point is Gondor's capital city, Minas Tirith.[8]

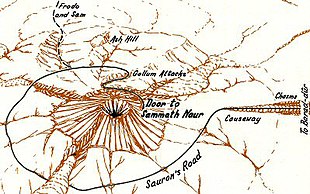

Across the river to the East is the land of Mordor. It is bordered to the north by the Ered Lithui, the Ash Mountains; to the west by the Ephel Duath, the Mountains of Shadow. Between those two ranges, at Mordor's northwest tip, are the Black Gates of the Morannon. In the angle between the two ranges is the volcanic Plateau of Gorgoroth, with the tall volcano of Orodruin or Mount Doom, where the Dark Lord Sauron forged the One Ring. To the mountain's east is Sauron's Dark Tower, Barad-dur.[9]

To the south of Gondor and Mordor lie Harad and Khand.[7]

Lands to the East

To the east of Rhovanion and to the north of Mordor lies the Sea of Rhûn, home to the Easterlings. North of that lie the Iron Hills of Dain's dwarves; between those and Mirkwood is Erebor, the Lonely Mountain, once home to Smaug the dragon, and afterwards to Thorin's dwarves.[10] The large lands to the east of Rhûn and to the south and east of Harad are not described in the stories, which take place in the north-western part of Middle-earth.[11][12]

Thematic mapping

The events of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings take place in the north-west of the continent of Middle-earth. Both quests begin in the Shire, travel east through the wilds of Eriador to Rivendell and then across the Misty Mountains, involve further travels in the lands of Rhovanion or Wilderland to the east of those mountains, and return home to the Shire. The cartographer Karen Wynn Fonstad prepared The Atlas of Middle-earth to clarify and map the two journeys – of Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit, and of Frodo Baggins in The Lord of the Rings – as well as the events described in The Silmarillion.[14] The editor of Tolkien Studies, David Bratman, notes that the atlas provides historical, geological, and battle maps, with a detailed commentary and explanation of how Fonstad approached the mapping task from the available evidence.[15] Michael Brisbois, also in Tolkien Studies, describes the atlas as "authorized",[16] while the cartographers Ina Habermann and Nikolaus Kuhn take Fonstad's maps as defining Middle-earth's geography.[17]

Stentor Danielson, a Tolkien scholar, notes that Tolkien did not provide the same "elaborate textual history" to contextualise his maps as he did for his writings. Danielson suggests that this has assisted the tendency among Tolkien's fans to treat his maps as "geographical fact".[13] He calls Fonstad's atlas "magisterial",[13] and comments that like Tolkien, Fonstad worked from the assumption that the maps, like the texts, "are objective facts" which the cartographer must fully reconcile. He gives as an instance the work that she did to make the journey of Thorin's company in The Hobbit consistent with the map, something that Tolkien found himself unable to do. Danielson writes that in addition, Fonstad created "the most comprehensive set" of thematic maps of Middle-earth, presenting geographic data including political boundaries, climate, population density, and the routes of characters and armies.[13]

Political geography

At the end of the Third Age, much of the northwest of Middle-earth is wild, with traces here and there of ruined cities and fortresses from earlier civilisations among the mountains, rivers, forests, hills, plains and marshes.[18] The major nations that appear in The Lord of the Rings are Rohan[19] and Gondor on the side of the Free Peoples,[20] and Mordor and its allies Harad (Southrons) and Rhûn (Easterlings) on the side of the Dark Lord.[21] Gondor, once extremely powerful, is by that time much reduced in its reach, and has lost control of Ithilien (bordering Mordor) and South Gondor (bordering Harad).[22] Forgotten by most of the rest of the world is the Shire, a small region in the northwest of Middle-earth inhabited by hobbits amidst the abandoned lands of Eriador.[23]

Analysis

Moral geography

With his "Southrons" from Harad, Tolkien had – in the view of John Magoun, writing in the J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia – constructed a "fully expressed moral geography",[11] from the hobbits' home in the Northwest, evil in the East, and "imperial sophistication and decadence" in the South. Magoun explains that Gondor is both virtuous, being West, and has problems, being South; Mordor in the Southeast is hellish, while Harad in the extreme South "regresses into hot savagery".[11] Steve Walker similarly speaks of "Tolkien's moral geography", naming the North "barbaric", South "the region of decadence", East "danger" but also the "locale of adventure", West "safety" (and uttermost West "ultimate safety"), North-West "specifically English insularity" where hobbits of the Shire live "in provincial satisfaction".[24]

Other scholars such as Walter Scheps and Isabel G. MacCaffrey have noted Middle-earth's "spatial cum moral dimensions",[25][26] though not identically with Magoun's interpretation. In their view, North and West are generally good, South and East evil. That places the Shire and the elves' Grey Havens in the Northwest as certainly good, and Mordor in the Southeast as certainly Evil; Gondor in the Southwest is in their view morally ambivalent, matching the characters of both Boromir and Denethor. They observe further that the Shire's four quadrants or "Farthings" serve as a "microcosm" of the moral geography of Middle-earth as a whole: thus, the evil Black Riders appear first in the Eastfarthing, while the once good but corrupted Saruman's men arrive in the Southfarthing.[25] J. K. Newman compares the adventurous quest to Mordor to "the perpetual temptation felt in the West 'to hold the gorgeous East in fee'" (citing Wordsworth on Venice), in a tradition which he traces back to Herodotus and to the myth of the Golden Fleece.[27]

Origins

Tolkien scholars including John Garth have traced many features of Middle-earth to literary sources or real-world places. Some places in Middle-earth can be more or less firmly associated with a single place in the real world, while other locations have had two or more real-world origins proposed for them. The sources are diverse, spanning classical, medieval, and modern elements.[28] Other elements relate to Old English poetry: several of the customs of Rohan in particular can be traced to Beowulf, on which Tolkien was an expert.[30]

Some Middle-earth placenames were based on the sound of places named in literature; thus, Beleriand was borrowed from the Broceliand of medieval romance.[29] Tolkien tried out many invented names in search of the right sound, in Beleriand's case including Golodhinand, Noldórinan ("valley of the Noldor"), Geleriand, Bladorinand, Belaurien, Arsiriand, Lassiriand, and Ossiriand (later used as a name for the easternmost part of Beleriand).[T 7] The Elves have been linked to Celtic mythology.[31] The Battle of the Pelennor Fields has parallels with the Battle of the Catalaunian Fields.[32] The Misty Mountains derive from the Poetic Edda, where the protagonist in the Skírnismál notes that his quest will involve misty mountains peopled with orcs and giants,[33] while the mountains' character was partly inspired by Tolkien's travels in the Swiss Alps in 1911.[T 8] Mirkwood is based on Myrkviðr, the romantic vision of the dark forests of the North.[34] Scholars have likened Gondor to Byzantium (medieval Istanbul),[35] while Tolkien connected it to Venice.[T 9] The Corsairs of Umbar have been linked to the Barbary corsairs of the late Middle Ages.[36] Númenor echoes the mythical Atlantis described by Plato.[T 10]

About the origins of his storytelling and the place of cartography within it, Tolkien stated in a letter:[33]

I wisely started with a map, and made the story fit (generally with meticulous care for distances). The other way about lands one in confusions and impossibilities, and in any case it is weary work to compose a map from a story.[T 11]

Writing in Mythlore, Jefferson P. Swycaffer suggested that the political and strategic situations of Gondor and Mordor in the Siege of Gondor were "analogous to Constantinople facing the boxshape of Asia Minor"; that "Dol Amroth makes a fine Venice"; that the Rohirrim and their grasslands are comparable to "Hungary of the Magyars, who were weak allies of Byzantine Constantinople"; and that the Corsairs of Umbar resembled the Barbary pirates who served Mehmed the Conqueror.[37]

The linguist David Salo writes that Gondor recalls "a kind of decaying Byzantium"; its piratical enemy Umbar like the seagoing Carthage; the Southrons (of Harad) "Arab-like"; and the Easterlings "suggesting Sarmatians, Huns and Avars".[38]

Geomorphology

The geologist Alex Acks, writing on Tor.com, outlines mismatches between Tolkien's maps and the processes of plate tectonics which shape the Earth's continents and mountain ranges. Acks comments that no natural process creates right-angle junctions in mountain ranges, such as are seen around Mordor and at both ends of the Misty Mountains on Tolkien's maps.[39] In addition, Tolkien's rivers fail to behave like natural rivers, forming regularly-branched streams in drainage basins demarcated by high ground.[40]

References

Primary

- ^ Carpenter 2023, 31

- ^ Tolkien 1954a, book 1, ch. 6 "The Old Forest"

- ^ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 9 "The Grey Havens", and Appendix B

- ^ Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ^ Tolkien 1980, pp. 271, 281

- ^ Tolkien 1937, p. 105

- ^ Tolkien 1986, "Commentary on Canto I"

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #306 to Michael Tolkien, 1967

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #168 to R. Jeffrey, September 1955

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #131 to Milton Waldman c. 1951, #154 to Naomi Mitchison 25 September 1954, #156 draft to Robert Murray 4 November 1954, #227 to Mrs E. C. Ossen Drijver 5 January 1961

- ^ Carpenter 2023, #144 to Naomi Mitchison, 25 April 1954

Secondary

- ^ a b c d Garbowski, Christopher (2013) [2007]. "Middle-earth". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 422–427. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 324–328 "The Lost Straight Road".

- ^ Larsen, Kristine (2008). Sarah Wells (ed.). "A Little Earth of His Own: Tolkien's Lunar Creation Myths". In the Ring Goes Ever on: Proceedings of the Tolkien 2005 Conference. 2. The Tolkien Society: 394–403.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 9–15.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 72–75.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 79–82.

- ^ a b Fonstad 1991, p. 53.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 83–89.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 90–93.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 76–77.

- ^ a b c d Magoun, John F. G. (2013) [2007]. "South, The". In Drout, Michael D.C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 622–623. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ Magoun, John F. G. (2013) [2007]. "East, The". In Drout, Michael D.C. (ed.). The J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-415-86511-1.

- ^ a b c d Danielson, Stentor (21 July 2018). "Re-reading the Map of Middle-earth: Fan Cartography's Engagement with Tolkien's Legendarium". Journal of Tolkien Research. 6 (1).

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. vii, ix–xi.

- ^ Bratman, David (2007). "Studies in English on the works of J.R.R. Tolkien". Tolkien Estate. Archived from the original on 15 May 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2021.

- ^ Brisbois, Michael J. (2005). "Tolkien's Imaginary Nature: An Analysis of the Structure of Middle-earth". Tolkien Studies. 2 (1): 197–216. doi:10.1353/tks.2005.0009. S2CID 170238657 – via Project Muse.

- ^ Habermann, Ina; Kuhn, Nikolaus (2011). "Sustainable Fictions – Geographical, Literary and Cultural Intersections in J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings". The Cartographic Journal. 48 (4): 263–273. doi:10.1179/1743277411y.0000000024. S2CID 140630128.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 132–133, 136–137.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 143–147, 151, 154.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 141–142.

- ^ Fonstad 1991, pp. 69–71.

- ^ Walker 2009, pp. 51–53.

- ^ a b Scheps, Walter (1975). "The Interlace Structure of 'The Lord of the Rings'". In Lobdell, Jared (ed.). A Tolkien Compass. Open Court. pp. 44–45. ISBN 978-0-8754-8303-0.

- ^ MacCaffrey, Isabel G. (1959). Paradise Lost as Myth. Harvard University Press. p. 55. OCLC 1041902253.

- ^ Newman, J. K. (2005). "J.R.R. Tolkien's 'The Lord of the Rings': A Classical Perspective". Illinois Classical Studies. 30: 229–247. JSTOR 23065305.

- ^ a b Main source is Garth, John (2020). The Worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien: The Places that Inspired Middle-earth. Frances Lincoln Publishers & Princeton University Press. pp. 12–13, 39, 41, 151, 32, 30, 37, 55, 88, 159–168, 175, 182 and throughout. ISBN 978-0-7112-4127-5.; minor sources are listed on the image's Commons page.

- ^ a b Fimi, Dimitra (2007). "Tolkien's 'Celtic type of legends': Merging Traditions". Tolkien Studies. 4: 53–72. doi:10.1353/tks.2007.0015. S2CID 170176739.

- ^ Shippey 2005, pp. 66–74, 90–97, and throughout

- ^ Fimi, Dimitra (August 2006). ""Mad" Elves and "Elusive Beauty": Some Celtic Strands of Tolkien's Mythology". Dimitra Fimi.

- ^ Solopova, Elizabeth (2009). Languages, Myths and History: An Introduction to the Linguistic and Literary Background of J. R. R. Tolkien's Fiction. New York City: North Landing Books. pp. 70-73. ISBN 978-0-9816607-1-4.

- ^ a b Shippey 2005, pp. 80–81, 114

- ^ Evans, Jonathan (2006). "Mirkwood". In Drout, Michael D. C. (ed.). J. R. R. Tolkien Encyclopedia: Scholarship and Critical Assessment. Routledge. pp. 429–430. ISBN 0-415-96942-5.

- ^ Librán-Moreno, Miryam (2011). "'Byzantium, New Rome!' Goths, Langobards and Byzantium in The Lord of the Rings". In Fisher, Jason (ed.). Tolkien and the Study of his Sources. MacFarland & Co. pp. 84–116. ISBN 978-0-7864-6482-1.

- ^ Bowers, John M. (2019). Tolkien's Lost Chaucer. Oxford University Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-19-258029-0.

- ^ Swycaffer, Jefferson (1983). "Historical Motivations for the Siege of Minas Tirith". Mythlore. 10. article 14.

- ^ Salo, David (2004). "Heroism and Alienation through Language in The Lord of the Rings". In Driver, Martha W.; Ray, Sid (eds.). The Medieval Hero on Screen: Representations from Beowulf to Buffy. McFarland. pp. 23–37. ISBN 978-0-7864-1926-5.

- ^ Acks 2017a.

- ^ Acks 2017b.

Sources

- Acks, Alex (1 August 2017a). "Tolkien's Map and The Messed Up Mountains of Middle-earth". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 1 August 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- Acks, Alex (10 October 2017b). "Tolkien's Map and the Perplexing River Systems of Middle-earth". Tor.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 6 October 2023.

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (2023) [1981]. The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien: Revised and Expanded Edition. New York: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-0-35-865298-4.

- Fonstad, Karen Wynn (1991). The Atlas of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-618-12699-6.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth: How J. R. R. Tolkien Created a New Mythology (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-261-10275-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1937). Douglas A. Anderson (ed.). The Annotated Hobbit. Boston: Houghton Mifflin (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-618-13470-0.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1954a). The Fellowship of the Ring. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 9552942.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1980). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). Unfinished Tales. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-29917-3.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1986). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Shaping of Middle-earth. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-42501-5.

- Walker, Steve (2009). The Power of Tolkien's Prose: Middle-Earth's Magical Style. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-61992-0.