Weather vane

A wind vane, weather vane, or weathercock is an instrument used for showing the direction of the wind. It is typically used as an architectural ornament to the highest point of a building. The word vane comes from the Old English word fana, meaning "flag".

Although partly functional, wind vanes are generally decorative, often featuring the traditional cockerel design with letters indicating the points of the compass. Other common motifs include ships, arrows, and horses. Not all wind vanes have pointers. In a sufficiently strong wind, the head of the arrow or cockerel (or equivalent) will indicate the direction from which the wind is blowing.

Wind vanes are also found on small wind turbines to keep the wind turbine pointing into the wind.

History

The oldest known textual references to weather vanes date from 1800-1600 BCE Babylon, where a fable called The Fable of the Willow describes people looking at a weather vane "for the direction of the wind."[1] In China, the Huainanzi, dating from around 139 BC, mentions a thread or streamer that another commentator interprets as "wind-observing fan" (hou feng shin, 侯風扇).[2]

The Tower of the Winds in the agora in Hellenistic Athens once bore on its roof a weather vane in the form of a bronze Triton holding a rod in his outstretched hand, rotating as the wind changed direction. Below this a frieze depicted the eight Greek wind deities. The eight-metre-high structure also featured sundials, and a water clock inside. It dated from around 50 BC.[3]

Military documents from the Three Kingdoms period of China (220–280 AD) refer to the weather vane as "five ounces" (wu liang, 五兩), named after the weight of its materials.[2] By the third century, Chinese weather vanes were shaped like birds and took the name of "wind-indicating bird" (xiang feng wu, 相風烏). The Sanfu huangtu (三輔黃圖), a third-century book written by Miao Changyan about the palaces at Chang'an, describes a bird-shaped weather vane situated on a tower roof.[2]

The oldest surviving weather vane with the shape of a rooster is the Gallo di Ramperto, made in 820 and now preserved in the Museo di Santa Giulia in Brescia, Lombardy.[4][5]

Pope Leo IV (in office 847 to 855) had a cock placed on the Old St. Peter's Basilica or old Constantinian basilica.[6]

Pope Gregory I (in office 590 to 604) regarded the cock as "the most suitable emblem of Christianity", being the emblem of Saint Peter (a reference to Luke 22:34 in which Jesus predicts that Peter will deny him three times before the rooster crows).[7][8]

As a result of this,[7] rooster representations gradually came into use as a weather vanes on church steeples, and in the ninth century Pope Nicholas I[9] (in office 858 to 867) ordered the figure to be placed on every church steeple.[10]

The Bayeux Tapestry of the 1070s depicts a man installing a cock on Westminster Abbey.

One alternative theory about the origin of weathercocks on church steeples sees them as emblems of the vigilance of the clergy calling the people to prayer.[11]

Another theory says that the cock was not a Christian symbol[12] but an emblem of the sun[13] derived from the Goths.[14]

A few churches used weather vanes in the shape of the emblems of their patron saints. The City of London has two surviving examples. The weather vane of St Peter upon Cornhill is not in the shape of a rooster, but of a key;[15] while St Lawrence Jewry's weather vane has the form of a gridiron (symbolising Saint Lawrence).[16]

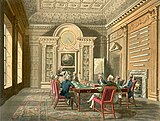

Early weather-vanes had very ornamental pointers, but modern weather-vanes usually feature simple arrows that dispense with the directionals because the instrument is connected to a remote reading station. An early example of this was installed in the Royal Navy's Admiralty building in London – the vane on the roof was mechanically linked to a large dial in the boardroom so senior officers were always aware of the wind direction when they met.

Modern aerovanes combine the directional vane with an anemometer (a device for measuring the speed of the wind). Co-locating both instruments allows them to use the same axis (a vertical rod) and provides a coordinated readout.

World's largest weather vane

According to the Guinness World Records, the world's largest weather vane is a Tío Pepe sherry advertisement located in Jerez, Spain. The city of Montague, Michigan also claims to have the largest standard-design weather vane, being a ship and arrow which measures 48 feet (15 m) tall, with an arrow 26 feet (7.9 m) long.[17]

A challenger for the title of the world's largest weather vane is located in Whitehorse, Yukon in Canada. The weather vane is a retired Douglas DC-3 CF-CPY atop a swiveling support. Located at the Yukon Transportation Museum[18] beside Whitehorse International Airport, the weather vane is used by pilots to determine wind direction, used as a landmark by tourists and enjoyed by locals. The weather vane only requires a 5 knot wind to rotate.[19]

A challenger for the world's tallest weather vane[citation needed] is located in Westlock, Alberta. The classic weather vane that reaches to 50 feet (15 m) is topped by a 1942 Case Model D Tractor. This landmark is located at the Canadian Tractor Museum.

Slang term

The term "weather vane" is also a slang word for a politician who has frequent changes of opinion. The National Assembly of Quebec has banned the use of this slang term as an insult after its use by members of the legislature.[20]

Literary references

- A copper-plated antique weathervane is the subject of the mystery in the children's book/Young Adult book entitled "The Mystery of the Phantom Grasshopper" (Trixie Belden series #18) by Kathryn Kenny, 1977. ISBN 0-307-21589-X. Paperback.

Gallery

- The Gallo di Ramperto, Museo di Santa Giulia in Brescia (Italy), the oldest surviving weather vane in the shape of a rooster in the world

- Creuë gibbet weather vane dating from the 17th century (France)

- Weather vanes on the Tallinn Town Hall, the taller one is the iconic Old Thomas

- Weather vane with dial, New Register House, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK

- Admiralty boardroom, 1808; a wind indicator can be seen on the end wall.

- Tío Pepe weather vane in Jerez, Guinness world record of the largest weather vane that works

- The Douglas DC-3 that now serves as a weather vane at Yukon Transportation Museum located beside the Whitehorse International Airport.

- A "jin-pole" being used to install a weather vane atop the 200 foot steeple of a church in Kingston, New York.

- Weathercock with verdigris patina

- Huge weather vane in Vilnius is among the largest in Europe

- Weather vane (video)

- Whirligig weather vane at the Minnesota History Center

- Weathercock on the former Thomas house, Kobe, Japan

See also

- Anemoscope

- Apparent wind indicator, in sailing

- List of weather instruments

- Weather station

- Windsock, in aviation

References

- ^ Neumann J. and Parpola, S. (1989), "Wind Vanes in Ancient Mesopotamia, About 2000-1500BC," Bulleting of the American Meteorological Society, vol. 64, No. 10

- ^ a b c Needham, Joseph; Ling, Wang (1959), Science and Civilisation in China: Mathematics and the Sciences of the Heavens and the Earth, vol. 3, Cambridge University Press, p. 478

- ^ Noble, Joseph V.; Price, Derek J. de Solla (October 1968). "The Water Clock in the Tower of the Winds". American Journal of Archaeology. 72 (4): 345–355 (353). doi:10.2307/503828. JSTOR 503828. S2CID 193112893.

- ^ Rossana Prestini, Vicende faustiniane, in AA.VV.,La chiesa e il monastero benedettino di San Faustino Maggiore in Brescia, Gruppo Banca Lombarda, La Scuola, Brescia 1999, p. 243

- ^ Fedele Savio, Gli antichi vescovi d'Italia. La Lombardia, Bergamo 1929, p. hi 188

- ^ ST PETER'S BASILICA.ORG - Providing information on St. Peter's Basilica and Square in the Vatican City - The Treasury Museum [1]

- ^ a b John G. R. Forlong, Encyclopedia of Religions: A-d - Page 471

- ^ Edward Walford; George Latimer Apperson (1888). The Antiquary: A Magazine Devoted to the Study of the Past. Vol. 17. E. Stock. p. 202.

- ^ Jerry Adler; Andrew Lawler (June 2012). "How the Chicken Conquered the World". Smithsonian.

- ^ Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum. Vol. 1–5. Pennsylvania Museum of Art, Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art. 1906. p. 14.

- ^ Thomas Ignatius M. Forster, Circle of the Seasons, p. 18

- ^ William White, Notes and Queries

- ^ Hargrave Jennings, Phallicism, p. 72

- ^ William Shepard Walsh, A Handy Book of Curious Information

- ^ "History of London: Vanity and Wind". Wordpress. Archived from the original on 13 October 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "Our Weather Vane". St Lawrence Jewry. Retrieved 1 June 2016.

- ^ "The World's Largest Weather Vane - Ella Ellenwood". Archived from the original on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2010-06-01.

- ^ goytm.ca

- ^ "DC-3 CF-CPY: The World's Largest Weather Vane - ExploreNorth". ExploreNorth. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ^ "Quebec bans 'weathervane' insult". Metro. 2007-10-17. Archived from the original on 2007-10-23. Retrieved 2019-06-18.

Further reading

- Bishop, Robert; Coblentz, Patricia (1981), A Gallery of American Weather Vanes and Whirligigs, New York: Dutton, ISBN 9780525931515

- Burnell, Marcia (1991), Heritage Above: a tribute to Maine's tradition of weather vanes, Camden, ME: Down East Books, ISBN 9780892722785

- Crépeau, Pierre; Portelance, Pauline (1990), Pointing at the Wind: the weather-vane collection of the Canadian Museum of Civilization, Hull, Quebec: Canadian Museum of Civilization, ISBN 9780660129044

- Fitzgerald, Ken (1967). Weathervanes & Whirligigs. New York: C. N. Potter.

- Kaye, Myrna (1975), Yankee Weathervanes, New York: Dutton, ISBN 9780525238591

- Klamkin, Charles (1973), Weather Vanes: The history, design and manufacture of an American folk art, New York: Hawthorn Books, OCLC 756017

- Lane Arts Council (Or.) (1994), Whirligigs & Weathervanes, Eugene, OR: Visual Arts Resources, OCLC 33052846

- Lynch, Kenneth; Crowell, Andrew Durkee (1971), Weathervanes, Architectural Handbook series, Canterbury, CN: Canterbury Publishing Company, OCLC 1945107

- Messent, Claude John Wilson (1937), The Weather Vanes of Norfolk & Norwich, Norwich: Fletcher & Son Limited, OCLC 5318669

- Miller, Steve (1984), The Art of the Weathervane, Exton, PA: Schiffer Pub., ISBN 9780887400056

- Mockridge, Patricia; Mockridge, Philip (1990), Weather Vanes of Great Britain, London: Hale, ISBN 9780709037224

- Needham, Albert (1953), English Weather Vanes, their stories and legends from medieval to modern times, Haywards Heath, Sussex: C. Clarke, OCLC 1472757

- Nesbitt, Ilse Buchert; Nesbitt, Alexander (1970), Weathercocks and Weathercreatures; some examples of early American folk art from the collection of the Shelburne Museum, Vermont, Newport, RI: Third & Elm Press, OCLC 155708

- Neumann, J.; Paropla, S. (1989), Wind Vanes in Ancient Mesopotamia, About 2000-1500 B.C., Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society

- Pagdin, W. E. (1949). The Story of the Weather Cock. Stockton-on-Tees: E. Appleby.

- Reaveley, Mabel E.; Kunhardt, Priscilla (1984), Weathervane Secrets, Dublin, NH: W. L. Bauhan, ISBN 9780872330757

- Westervelt, A. B.; Westervelt, W. T. (1982), American Antique Weather Vanes: The Complete Illustrated Westervelt Catalog of 1883, New York: Dover, ISBN 9780486243962

External links

![]() Media related to Weather vanes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Weather vanes at Wikimedia Commons

![Weathercock on the former Thomas house [ja], Kobe, Japan](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a1/Weathercock_of_Former_Tohmas_House_20110313.jpg/113px-Weathercock_of_Former_Tohmas_House_20110313.jpg)