Packaging waste

| Part of a series on |

| Pollution |

|---|

|

Packaging waste, the part of the waste that consists of packaging and packaging material, is a major part of the total global waste, and the major part of the packaging waste consists of single-use plastic food packaging, a hallmark of throwaway culture.[1][2] Notable examples for which the need for regulation was recognized early, are "containers of liquids for human consumption", i.e. plastic bottles and the like.[3] In Europe, the Germans top the list of packaging waste producers with more than 220 kilos of packaging per capita.[2]

Background

According to the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), defined containers and packaging as products that are assumed to be discarded the same year the products they contain are purchased.[5] The majority of the solid waste are packaging products, estimating to be about 77.9 million tons of generation in 2015 (29.7 percent of total generation).[5] Packaging can come in all shapes and forms ranging from Amazon boxes to soda cans and are used to store, transport, contain, and protect goods to keep customer satisfaction. The type of packaging materials including glass, aluminum, steel, paper, cardboard, plastic, wood, and other miscellaneous packaging.[5] Packaging waste is a dominant contributor in today's world and responsible for half of the waste in the globe.[4]

The recycling rate in 2015 for containers and packaging was 53 percent. Furthermore, the process of burning of containers and packaging was 7.2 million tons (21.4 percent of total combustion with energy recovery). Following the landfills that received 29.4 million tons (21.4 percent of total land filling) within the same year.[5]

As packaging waste pollutes the Earth, all life on Earth experiences negative impacts that affected their lifestyle. Marine or land-living animals are suffocating due to the pollution of packaging waste.[4] This is a major issue for low income countries who do not have an efficient waste management system to clean up their environments and being the main sources for the global ocean pollution.[4] But 'litter louts', individuals who lack the motivation to recycle and instead leave their waste anywhere they want are also major contributors, especially in high income nations where such facilities are available. The current location with the greatest amount of solid waste that includes most of packaging products is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch located at West Coast of North America to Japan.[4][6] Most packaging waste that eventually goes into the ocean often comes from places such as lakes, streams, and sewage.

Possible solutions to reducing packaging waste are very simple and easy and could start with minimisation of packaging material ranging up to a zero waste strategy (package-free products[7]). The problem is mainly in a lack of motivation to start making a change. But examples of effective ways to help reduce packaging pollution include banning the use of single-use plastics, more social awareness and education, promotion of eco-friendly alternatives, public pressure, voluntary cleaning up, and adopting reusable or biodegradable bags.[8]

Overpackaging

The Institute of Packaging Professionals defines overpackaging as "a condition where the methods and materials used to package an item exceed the requirements for adequate containment, protection, transport, and sale."[9] Overpackaging is an opportunity for source reduction, reducing waste by proper package design and practice.

A classic example of a wasteful package design is a breakfast cereal box. This is typically a folding carton enclosing a plastic bag of cereal. Cartons are typically tall and wide but very thin. This has an inefficient material-to-volume ratio; it is wasteful. Structural packaging engineers are aware of the opportunity to save packaging costs, materials, and waste but marketers find benefit in a "billboard" style package for advertising and graphics. An optimized folding box would use much less paperboard for the same volume of cereal, but with reduced surface area for graphics. The use of a plastic bag without an enclosing box would use less material per unit of cereal.[10]

Slackfill packaging is that which is intentionally under-filled, resulting in non-functional headspace. Packagers doing this not only risk charges of deceptive packaging but are using excessive packaging: packaging waste.[11]

With fragile items such as consumer electronics, engineers try to match the fragility of the product with the expected stresses of distribution handling. Package cushioning is used to help ensure safe delivery of the product. With overpackaging, excessive cushion and a larger corrugated box are used: wasteful packaging. Conversely, underpackaging would be the use of insufficient cushioning. Excessive product waste caused by underpackaging may be worse for the environment than the waste of the package.

Sometimes packaging is designed to protect its product for controlled distribution to a retail store. With online shopping or E-commerce, however, items packed for retail sale may be shipped individually by Fulfillment houses by package delivery or small parcel carriers. Retail packages are frequently packed into a larger corrugated box for shipment. Often these secondary boxes are much larger than needed, thus use void-fill to immobilize the contents. The rapid growth of e-commerce has increased packaging challenges, as items often require additional protective materials and oversized boxes to ensure safe transportation, which further exacerbates packaging waste.[12] This can have the appearance of gross overpackaging but is sometimes necessary. If the product packager designed all packaging to meet the requirements of individual shipment, then the portion delivered to a retail store would have excessive packaging. Sometimes two levels of packaging are needed for separate distribution, resulting in production inefficiencies.[13]

Types of packaging wastes

Glass containers

Bottles and jars for drinks and storing foods or juices are examples of glass containers. It has been estimated by the EPA that 9.1 million tons of glass containers were generated in 2015, or 3.5 percent of municipal solid waste (MSW).[5] About 70 percent of glass consumption is used for containers and packaging purposes.[14] At least 13.2 percent of the production of glass and containers are burned with energy recovery.[5] The amount of glass containers and packaging going into the land fill is about 53 percent.[5]

Aluminum containers and packaging

Aluminum container and packaging waste usually comes from cans from any kind of beverages, but foil can also be another that contributes it as well. It has been given that about 25 percent of aluminum is used for packaging purposes.[14] Using the Aluminum Association Data, it has been calculated that at least 1.8 million tons of aluminum packaging were generated in 2015 or 0.8 percent MSW produced.[5] Of those that are produced, only about 670,000 tons of aluminum containers and packaging were recycled, about 54.9 percent.[5] And, the ones that ends up in the land fill is 50.6 percent.[5]

Steel containers and packaging

The production of steel containers and packaging mostly comes in cans and other things like steel barrels. Only about 5 percent of steel use for packaging purposes of the total world of steel consumption which makes it the least amount wasted and the most recycled.[14] It has totaled that 2.2 million tons or 0.9 percent of MSW generated in 2015.[14] While according to the Steel Recycling Institute, an estimate of 1.6 million tons (73 percent) of steel packaging were recycled.[14] Adding on, the steel packaging that were combusted with energy recover was about 5.4 percent and 21.6 percent were land filled.[5]

Paper and paperboard containers and packaging

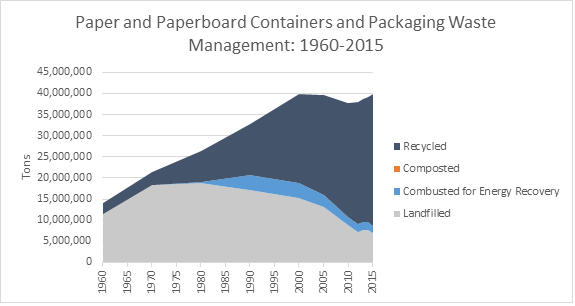

The most of it being generated, and within the MSW in 2015, was corrugated boxes coming with at least 31.3 million tons (11.3 percent total) produced.[5] However, it also the top most recycled at 28.9 million tons (92.3 percent) boxes being recycled in 2015.[5]

Later on, they are then combusted which makes 0.5 million tons and landfills received 1.9 million tons.[5] Other than corrugated boxes, cartons, bags, sacks, wrapping papers, and other boxes used for shoes or cosmetics are other examples of paper and paperboard containers and packaging. The total amount of MSW generated for paper and paperboard containers and packaging was 39.9 million tons or 15.1 percent in 2015. Although, the recycled rate is about 78.2 percent and 4.3 percent of small proportions were combusted with energy recovery and 17.6 percent in landfill.

Wood packaging

Wood packaging is anything that is made out of wood used for packaging purposes (e.g., wood crates, wood chips, boards, and planks). Wood packaging is still highly used in today's world for transporting goods. According to EPA's data that were borrowed from the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and the United States Department of Agriculture's Forest Service Southern Research Station, 9.8 million tons (3.7 percent of total MSW) of wood packaging were made in production in 2015.[5] Also, in 2015, the amount that was recycled 2.7 million tons.[5] Moreover, its estimated that 14.3 percent of the wood containers and packaging waste generated was combusted with energy recovery, while the 58.6 percent went to the land filled.

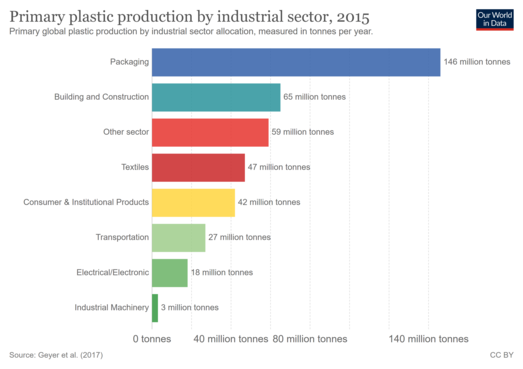

Plastic containers and packaging

Plastic containers and packaging can be found in plastic bottles, supermarket bags, milk and water jugs, and more. EPA used data from the American Chemistry Council to estimate that 14.7 million tons (5.5 percent of MSW generation) of plastic containers and packaging were created in 2015.[5] The overall amount that is recycled is about 2.2 million tons (14.6 percent).[5] In addition, 16.8 percent were combusted with energy recover and 68.6 percent went straight into the land fill.[5] Most of the plastics are made from polyethylene terephthalate (PET), high-density polyethylene (HDPE), low-density polyethylene (LDPE), polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polystyrene (PS), polypropylene (PP) and other resins.[5] That being said, the recycling rate for PET bottles and jars was 29.9 percent (890,000 tons) and the recycling of HDPE water and milk jugs was 30.3 percent (230,000 tons).[5]

Role of packaging waste in pollution

Litter

Litter mostly consists of packaging waste. Besides the disfigurement of the landscape, it also poses a health hazard for various life forms.[14] Packaging materials such as glass and plastic bottles are the main constituents of litter.[14] It has a huge impact on the marine environment as well, when animals are caught in or accidentally consume plastic packaging.

Air pollution

The production of packaging material is the main source of the air pollution that is being spread globally. Some emissions comes from accidental fires or activities that includes incineration of packaging waste that releases vinyl chloride, CFC, and hexane.[14] For a more direct course, emissions can originate in land fill sites which could release CO2 and methane.[14] Most CO2 comes from steel and glass packaging manufacturing.[14]

Water pollution

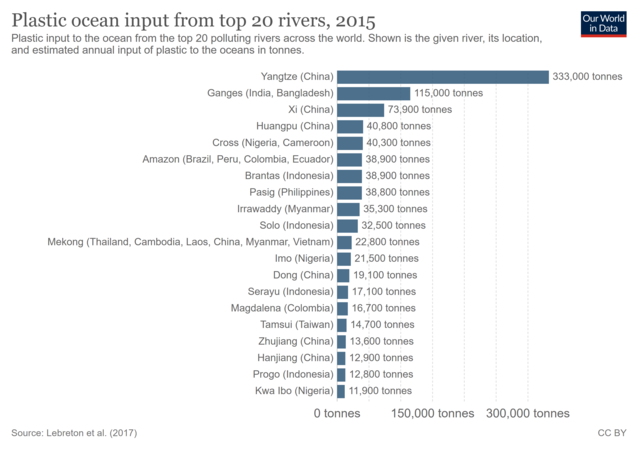

Packaging waste can come from land based or marine sources. The current location that makes up the large of amount of water pollution is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch located at West Coast of North America to Japan.[4][6] Marine sources such as rivers that caught packaging materials eventually lead to the oceans. In global standards, about 80 percent of packaging waste in ocean comes from land based sources and 20 percent comes from marine sources.[4] The 20 percent of packaging waste that comes from marine sources comes from the rivers of China starting from least to greatest contributors, the Hanjiang, Zhujiang, Dong, Huangpu, Xi, and Yangtze river.[4] All other marine sources comes from rivers of Africa and Southeast Asia.[4]

Impacts on marine species and wildlife species

Most marine species and wildlife species suffer from the following:

- Entanglement: At least 344 species are entangled by packaging waste, specifically the ones that are plastics.[4] Most of the victims are marine species like whales, seabirds, turtles, and fish.[4][6]

- Ingestion: 233 marine species are recorded that had consumed plastic packaging waste of either unintentionally, intentionally, or indirectly.[4] Again, the following victims would be whales, fish, mammals, seabirds, and turtles.[4][6] The effects of eating plastic packaging waste could lead to greatly reduced stomach capacity, leading to poor appetite and false sense of satiation.[4] Whats worse is that the size of the ingested material is ultimately limited by the size of the organism.[4] For example, microplastics consumed by planktons and fishes can consume cigarettes boxes.[4][6] Plastic can also obstruct or perforate the gut, cause ulcerative lesions, or gastric rupture.[4][6] This can ultimately lead to death.

- Interaction: Animals contacting with packaging waste includes collisions, obstructions, abrasions or use as substrate.[4]

Impacts on human health

Bisphenol A (BPA), styrene and benzene can be found in certain packaging waste.[6][8] BPA can affect the hearts of women, permanently damage the DNA of mice, and appear to be entering the human body from a variety of unknown sources.[6] Studies from Journal of American Association shows that higher bisphenol A levels were significantly associated with heart diseases, diabetes, and abnormally high levels of certain liver enzymes.[6] Toxins such as these are found within our food chains. When fish or plankton consume microplastics, it can also enter our food chain.[4][8] Microplastics was also found in common table salt and in both tap and bottled water.[8] Microplastics are dangerous as the toxins can affect the human body's nervous, respiratory, and reproductive system.[4][6][14]

Actions to reduce packaging wastes

Waste management system improvements

- Segregation of waste at sources: plastics, organic, metals, paper, etc.[8]

- Effective collection of the segregated waste, transport and safe storage[8]

- Cost-effective recycling of materials (including plastics)[8]

- Less land filling and dumping in the environment[8]

Promotion of eco-friendly alternatives

Governments working with industries could support the development and promotion of sustainable alternatives in order to phase out single-use plastics progressively.[8] If governments were to introduce economic incentives, supporting projects which upscale or recycle single-use items and stimulating the creation of micro-enterprises, they could contribute to the uptake of eco-friendly alternatives to single-use plastics.[8]

Social awareness and education

Social awareness and education are also ways to help contribute to issues similar to helping reduce packaging waste. Using the media gives individuals or groups quick access to spread information and awareness concerning letting the public know what is happening in the world and how others can contribute to fixing packaging waste problems. Schools are also good for spreading education with factual knowledge and possible outcomes for the increase of packaging waste and provide ways to get individuals to give a helping hand in keeping our planet clean. Public awareness strategies can include various activities designed to persuade and educate.[8] These strategies may focus on the reuse and recycling of resources and encouraging responsible use and minimization of waste generation and litter.[8]

Voluntarily actions to reduce packaging waste

- Reuse bags

- Bring reusable bags to supermarkets[8]

- Repair broken objects instead of throwing them away[8]

- Exchange packaging materials on BoxGiver

- Recycle

- Clean up in coastal areas

- Do community services to clean up parks and streets from packaging waste

See also

- Plastic waste – Accumulation of plastic in natural ecosystems

- Waste & Resources Action Programme – British charitable organization

- Packaging Recovery Note – documenting packaging recycling

- Packaging and packaging waste directive – Directive of EU

- Producer Responsibility Obligations (Packaging Waste) Regulations 2007 – UK waste management regulations

- Reusable packaging – Packaging designed for reuse

- Sustainable packaging – Packaging which results in improved sustainability

- Fast food – Food prepared and served in a small amount of time

- Waste minimization – Process that involves reducing the amount of waste produced in society

- Circular economy – Production model to minimise wastage and emissions

- Disposable food packaging

References

- ^ Hall, Dave (2017-03-13). "Waste packaging". the Guardian. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- ^ a b Local, DPA/The (2018-07-26). "Germany accumulates more packaging waste per capita than any country in the EU". The Local. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- ^ "Packaging waste - Environment". European Commission. Retrieved 2019-02-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (September 1, 2018). "Plastic Pollution". Our World in Data. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa US EPA, OLEM (September 7, 2017). "Containers and Packaging: Product-Specific Data". US EPA. Retrieved October 29, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Guren, Claire Le (November 2009). "Plastic Pollution". Coastal Care. Retrieved October 30, 2019.

- ^ "Please don't package it!". 18 January 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Giacovelli, Claudia (2018). Single-use plastics, a roadmap for sustainability. Nairobi, Kenya: United Nations Environment Programme. ISBN 9789280737059. OCLC 1096282673.

- ^ Soroka, W. Illustrated Glossary of Packaging Terminology (Second ed.). Institute of Packaging Professionals.

- ^ Fitzgerald (August 2004). "Cereal Box Design" (PDF). Tech Directions: 22. Retrieved 4 November 2021.

- ^ Misleading Containers, 21CFR100.100

- ^ "Addressing Plastic Packaging Waste in E-commerce Retail". SDG Knowledge Hub. Retrieved 2024-11-16.

- ^ Escursel, S (1 January 2021). "Sustainability in e-commerce packaging: A review". Journal of Cleaner Production. 280: 124314. Bibcode:2021JCPro.28024314E. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.124314. PMC 7511172. PMID 32989345.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Pongrácz, Eva (March 23, 2007), "The Environmental Impacts of Packaging", Environmentally Conscious Materials and Chemicals Processing, pp. 237–278, ISBN 9780470168219, retrieved October 30, 2019