Wallpaper

Wallpaper is used in interior decoration to cover the interior walls of domestic and public buildings. It is usually sold in rolls and is applied onto a wall using wallpaper paste. Wallpapers can come plain as "lining paper" to help cover uneven surfaces and minor wall defects, "textured", plain with a regular repeating pattern design, or with a single non-repeating large design carried over a set of sheets.

The smallest wallpaper rectangle that can be tiled to form the whole pattern is known as the pattern repeat. Wallpaper printing techniques include surface printing, rotogravure, screen-printing, rotary printing press, and digital printing.

Modern wallpaper

Modern wallpaper is made in long rolls which are hung vertically on a wall. Patterned wallpapers are designed so that the pattern "repeats", and thus pieces cut from the same roll can be hung next to each other so as to continue the pattern without it being easy to see where the join between two pieces occurs. In the case of large complex patterns of images this is normally achieved by starting the second piece halfway into the length of the repeat, so that if the pattern going down the roll repeats after 24 inches (610 mm), the next piece sideways is cut from the roll to begin 12 inches (300 mm) down the pattern from the first. The number of times the pattern repeats horizontally across a roll does not matter for this purpose. A single pattern can be issued in several different colorways.

History

The main historical techniques are hand-painting, woodblock printing (overall the most common), stencilling, and various types of machine printing. The first three all date back to before 1700.[1]

Wallpaper, using the printmaking technique of woodcut, gained popularity in Renaissance Europe amongst the emerging gentry. The social elite continued to hang large tapestries on the walls of their homes, as they had in the Middle Ages. These tapestries added color to the room as well as providing an insulating layer between the stone walls and the room, thus retaining heat in the room. However, tapestries were extremely expensive and so only the very rich could afford them. Less well-off members of the elite, unable to buy tapestries due either to prices or wars preventing international trade, turned to wallpaper to brighten up their rooms.

Early wallpaper featured scenes similar to those depicted on tapestries, and large sheets of the paper were sometimes hung loosely on the walls, in the style of tapestries, and sometimes pasted as today. Prints were very often pasted to walls, instead of being framed and hung, and the largest sizes of prints, which came in several sheets, were probably mainly intended to be pasted to walls. Some important artists made such pieces – notably Albrecht Dürer, who worked on both large picture prints and also ornament prints – intended for wall-hanging. The largest picture print was The Triumphal Arch commissioned by the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I and completed in 1515. This measured a colossal 3.57 by 2.95 metres (11.7 by 9.7 ft), made up of 192 sheets, and was printed in a first edition of 700 copies, intended to be hung in palaces and, in particular, town halls, after hand-coloring.

Very few samples of the earliest repeating pattern wallpapers survive, but there are a large number of old master prints, often in engraving of repeating or repeatable decorative patterns. These are called ornament prints and were intended as models for wallpaper makers, among other uses.

England and France were leaders in European wallpaper manufacturing. Among the earliest known samples is one found on a wall from England and is printed on the back of a London proclamation of 1509. It became very popular in England following Henry VIII's excommunication from the Catholic Church – English aristocrats had always imported tapestries from Flanders and Arras, but Henry VIII's split with the Catholic Church had resulted in a fall in trade with Europe. Without any tapestry manufacturers in England, English gentry and aristocracy alike turned to wallpaper.

During the Protectorate under Oliver Cromwell, the manufacture of wallpaper, seen as a frivolous item by the Puritan government, was halted. Following the Restoration of Charles II, wealthy people across England began demanding wallpaper again – Cromwell's Puritan regime had imposed a repressive and restrictive culture on the population, and following his death, wealthy people began purchasing comfortable domestic items which had been banned under the Puritan state.

18th century

In 1712, during the reign of Queen Anne, a wallpaper tax was introduced which was not abolished until 1836. By the mid-18th century, Britain was the leading wallpaper manufacturer in Europe, exporting vast quantities to Europe in addition to selling on the middle-class British market. However this trade was seriously disrupted in 1755 by the Seven Years' War and later the Napoleonic Wars, and by a heavy level of duty on imports to France.

In 1748 the British Ambassador to Paris decorated his salon with blue flock wallpaper, which then became very fashionable there. In the 1760s the French manufacturer Jean-Baptiste Réveillon hired designers working in silk and tapestry to produce some of the most subtle and luxurious wallpaper ever made. His sky blue wallpaper with fleurs-de-lys was used in 1783 on the first balloons by the Montgolfier brothers.[1] The landscape painter Jean-Baptiste Pillement discovered in 1763 a method to use fast colours.

Hand-blocked wallpapers like these use hand-carved blocks and by the 18th century designs include panoramic views of antique architecture, exotic landscapes and pastoral subjects, as well as repeating patterns of stylized flowers, people and animals.

In 1785 Christophe-Philippe Oberkampf had invented the first machine for printing coloured tints on sheets of wallpaper. In 1799 Louis-Nicolas Robert patented a machine to produce continuous lengths of paper, the forerunner of the Fourdrinier machine. This ability to produce continuous lengths of wallpaper now offered the prospect of novel designs and nice tints being widely displayed in drawing rooms across Europe.

Wallpaper manufacturers active in England in the 18th century included John Baptist Jackson[1] and John Sherringham.[2] Among the firms established in 18th-century America: J. F. Bumstead & Co. (Boston), William Poyntell (Philadelphia), John Rugar (New York).[1]

High-quality wallpaper made in China became available from the later part of the 17th century; this was entirely handpainted and very expensive. It can still be seen in rooms in palaces and grand houses including Nymphenburg Palace, Łazienki Palace, Chatsworth House, Temple Newsam, Broughton Castle, Lissan House, and Erddig. It was made up to 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) wide. English, French and German manufacturers imitated it, usually beginning with a printed outline which was coloured in by hand, a technique sometimes also used in later Chinese papers.

France and America

Towards the end of the 18th century the fashion for scenic wallpaper revived in both America and France, leading to some enormous panoramas, like the 1804 20 strip wide panorama, Sauvages de la Mer du Pacifique (Savages of the Pacific), designed by the artist Jean-Gabriel Charvet for the French manufacturer Joseph Dufour et Cie showing the Voyages of Captain Cook.[3] This famous so-called "papier peint" wallpaper is still in situ in Ham House, Peabody, Massachusetts.[4] It was the largest panoramic wallpaper of its time, and marked the burgeoning of a French industry in panoramic wallpapers. Dufour realized almost immediate success from the sale of these papers and enjoyed a lively trade with America. The Neoclassical style currently in favour worked well in houses of the Federal period with Charvet's elegant designs. Like most 18th-century wallpapers, the panorama was designed to be hung above a dado.

Beside Joseph Dufour et Cie (1797 – c. 1830) other French manufacturers of panoramic scenic and trompe-l'œil wallpapers, Zuber et Cie (1797–present) and Arthur et Robert exported their product across Europe and North America. Zuber et Cie's c. 1834 design Views of North America[5] hangs in the Diplomatic Reception Room of the White House.

Among the firms begun in France in the 19th century: Desfossé & Karth.[1] In the United States: John Bellrose, Blanchard & Curry, Howell Brothers, Longstreth & Sons, Isaac Pugh in Philadelphia; Bigelow, Hayden & Co. in Massachusetts; Christy & Constant, A. Harwood, R. Prince in New York.[6]

The earliest known American wallpaper sample book that has survived to present day resides in the collection of Old Sturbridge Village in Sturbridge, Massachusetts. It was produced by the firm Janes & Bolles of Hartford, Connecticut, between 1821 and 1828.[7]

England

During the Napoleonic Wars, trade between Europe and Britain evaporated, resulting in the gradual decline of the wallpaper industry in Britain. However, the end of the war saw a massive demand in Europe for British goods which had been inaccessible during the wars, including cheap, colourful wallpaper. The development of steam-powered printing presses in Britain in 1813 allowed manufacturers to mass-produce wallpaper, reducing its price and so making it affordable to working-class people. Wallpaper enjoyed a huge boom in popularity in the nineteenth century, seen as a cheap and very effective way of brightening up cramped and dark rooms in working-class areas. It became almost the norm in most areas of middle-class homes, but remained relatively little used in public buildings and offices, with patterns generally being avoided in such locations. In the latter half of the century Lincrusta and Anaglypta, not strictly wallpapers, became popular competitors, especially below a dado rail. They could be painted and washed, and were a good deal tougher, though also more expensive.

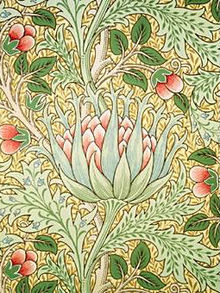

Wallpaper manufacturing firms established in England in the 19th century included Jeffrey & Co.; Shand Kydd Ltd.;[1] Lightbown, Aspinall & Co.;[1] John Line & Sons;[1] Potter & Co.;[8] Arthur Sanderson & Sons; Townshend & Parker.[9] Designers included Owen Jones, William Morris, and Charles Voysey. In particular, many 19th century designs by Morris & Co and other Arts and Crafts Movement designers remain in production.

20th century

By the early 20th century wallpaper had established itself as one of the most popular household items across the Western world. Manufacturers in the USA included Sears;[10] designers included Andy Warhol.[11] Wallpaper has gone in and out of fashion since about 1930, but the overall trend has been for wallpaper-type patterned wallcoverings to lose ground to plain painted walls.

21st century

In the early 21st century wallpaper evolved into a lighting feature, enhancing the mood and the ambience through lights and crystals. Meystyle, a London-based company, invented LED-incorporated wallpaper.[12] The development of digital printing allows designers to break the mould and combine new technology and art to bring wallpaper to a new level of popularity.[13]

Historical collections

Historical examples of wallpaper are preserved by cultural institutions such as the Deutsches Tapetenmuseum (Kassel) in Germany;[14] the Musée des Arts Décoratifs (Paris) and Musée du Papier Peint (Rixheim) in France;[1] the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in the UK;[15] the Smithsonian's Cooper-Hewitt,[16] Historic New England,[17] Metropolitan Museum of Art,[18] U.S. National Park Service,[19][20] and Winterthur[21] in the US. Original designs by William Morris and other English wallpaper companies are held by Walker Greenbank.

Types and sizes

In terms of methods of creation, wallpaper types include painted wallpaper, hand-printed blockwood wallpaper, hand-printed stencil wallpaper, machine-printed wallpaper, and flock wallpaper.[1]

Modern wallcoverings are diverse, and what is described as wallpaper may no longer actually be made from paper. Two of the most common factory trimmed sizes of wallpaper are referred to as "American" and "European" rolled goods. American rolled goods are 27 inches (69 cm) by 27 feet (8.2 m) in length. European rolled goods are 52 centimetres (20 in) wide by 10 metres (33 ft) in length,[22] approximately 5.2 square metres (56 sq ft). Most wallpaper borders are sold by length and with a wide range of widths therefore surface area is not applicable, although some may require trimming.

The most common wall covering for residential use and generally the most economical is prepasted vinyl coated paper, commonly called "strippable" which can be misleading. Cloth backed vinyl is fairly common and durable. Lighter vinyls are easier to handle and hang. Paper backed vinyls are generally more expensive, significantly more difficult to hang, and can be found in wider untrimmed widths. Foil wallpaper generally has paper backing and can (exceptionally) be up to 36 inches (91 cm) wide, and be very difficult to handle and hang. Textile wallpapers include silks, linens, grass cloths, strings, rattan, and actual impressed leaves. There are acoustical wall carpets to reduce sound. Customized wallcoverings are available at high prices and most often have minimum roll orders.

Solid vinyl with a cloth backing is the most common commercial wallcovering [citation needed] and comes from the factory as untrimmed at 54 inches (140 cm) approximately, to be overlapped and double cut by the installer. This same type can be pre-trimmed at the factory to 27 inches (69 cm) approximately.

Modern developments

Custom printing

New digital inkjet printing technologies using ultraviolet (UV) cured inks are being used for custom wallpaper production. Very small runs can be made, even a single wall. Photographs or digital art are output onto blank wallpaper material. Typical installations are corporate lobbies, restaurants, athletic facilities, and home interiors. This gives a designer the ability to give a space the exact look and feel desired.

High-tech

New types of wallpaper under development or entering the market in the early 21st century include wallpaper that blocks certain mobile phone and WiFi signals, in the interest of privacy. The wallpaper is coated with a silver ink which forms crystals that block outgoing signals.[23]

Seismic

In 2012 scientists at the Institute of Solid Construction and Construction Material Technology at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology announced that they had developed a wallpaper that can help keep a masonry wall from failing in an earthquake. The wallpaper uses glass fibre reinforcement in several directions and a special adhesive which forms a strong bond with the masonry when dry.[24]

As a means of artistic expression

Tsang Kin-Wah, one of Hong Kong's best-known painters,[25] creates large-scale wallpaper installations that evoke the floral designs of William Morris in a style that has become known as word-art installation.[26]

Installation

Like paint, wallpaper requires proper surface preparation before application. Additionally wallpaper is not suitable for all areas. For example, bathroom wallpaper may deteriorate rapidly due to excessive steam (if is not sealed with a specific varnish). Proper preparation includes the repair of any defects in the drywall or plaster and the removal of loose material or old adhesives. For a better finish with thinner papers and poorer quality walls the wall can be cross-lined (horizontally) with lining paper first. Accurate room measurements (length, width, and height) along with number of window and door openings is essential for ordering wallpaper. Large drops, or repeats, in a pattern can be cut and hung more economically by working from alternating rolls of paper.[27]

After pre-pasted wallpaper is moistened, or dry wallpaper is coated with wet paste, the wet surface is folded onto itself and left for a few minutes to activate the glue, which is called "booking wallpaper."[28]

Besides conventional installation on interior walls and ceilings, wallpapers have been deployed as decorative covering for hatboxes, bandboxes, books, shelves, and window-shades.[29]

Wallpaper adhesives

Most wallpaper adhesives are starch or methylcellulose based.

See also

- Faux painting

- List of wallpaper manufacturers

- Mural

- Wall decals

- Wallpaper group

- William Morris wallpaper designs

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Grove Art Online "Wallpaper", Oxford Art Online

- ^ Bulletin of the City Art Museum of St. Louis, Vol. 15, No. 2, 1930

- ^ Joseph Dufour (1804), Les sauvages de la mer Pacifique, tableau pour décoration en papier peint, A Macon [France?]: De l'Imprimerie de Moiroux, rue franche, ISBN 0665141149, OL 23705116M, 0665141149

- ^ Horace H. F. Jayne. Captain Cook Wallpaper. Bulletin of the Pennsylvania Museum, Vol. 17, No. 69 (Oct., 1921)

- ^ R. P. Emlen: ‘Imagining America in 1834: Zuber's Scenic Wallpaper "Vues d'Amérique du Nord"’, Winterthur Port., xxxii (Summer–Aug 1997)

- ^ Decorator and Furnisher, Vol. 16, No. 6 (Sep., 1890)

- ^ "The Rosetta Stone of Wallpaper?". www.cooperhewitt.org. Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. 2014-09-22. Retrieved 2021-07-20.

- ^ Sugden, A.V, Potters of Darwen 1839–1939 a century of wallpaper printing by machinery. 1939

- ^ Official descriptive and illustrated catalogue, Great exhibition of the works of industry of all nations, London: Spicer Brothers, 1851, OCLC 1044640, OL 6962338M

- ^ Wall paper, Chicago [Ill.]: Sears, Roebuck and Co., 1900, OCLC 17573461, OL 25126572M

- ^ Hapgood. Wallpaper and the artist: from Durer to Warhol. London: Abbeville Press, 1992

- ^ Surya, Shirley (2008). "Patterns: Design, Architecture, Interiors", page 204. DOM Publishers, Singapore. ISBN 978-3938666715

- ^ Swengley, N. [1], London, 20 March 2010. Retrieved on 30 June 2015

- ^ E. W. Mick. Hauptwerke des Deutschen Tapetenmuseum in Kassel (Tokyo, 1981)

- ^ "Wallpaper". London: V&A.

- ^ "Cooper-Hewitt". USA.

- ^ "Wallpaper Search Collection". USA: Wallpaper Historic New England. Retrieved 21 December 2023.

- ^ "Metropolitan Museum of Art". NY.

- ^ Patricia Hamm and James Hamm. The Removal and Conservation Treatment of a Scenic Wallpaper, "Paysage à Chasses," from the Martin Van Buren National Historic Site. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Vol. 20, No. 2, Conservation of Historic Wallpaper (Spring, 1981)

- ^ Thomas K. McClintock. The In situ Treatment of the Wallpaper in the Study of the Longfellow National Historic Site. Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, Vol. 20, No. 2, Conservation of Historic Wallpaper (Spring, 1981)

- ^ Horace L. Hotchkiss, Jr. Wallpaper from the Shop of William Poyntell. Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 4 (1968)

- ^ "Paint & Wallpaper: How to decorate your home". www.johnlewis.com.

- ^ Peter Leggatt and Nathan Brooker (February 22, 2013). "The new role of wallpaper". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ "High-tech wallpaper resists earthquakes". UPI. April 4, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ^ J.P. (May 23, 2013). "Art Basel Hong Kong – Local Pride". The Economist. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ^ Isabella Tam (January 26, 2016). "Tsang Kin-wah And The Organic Necessity Of Art". The Culture Trip. Retrieved February 7, 2016.

- ^ "How To Hang Wallpaper". Primetime Paint & Paper. 8 February 2013. Retrieved 13 December 2013.

- ^ "How to Hang Wallpaper". thisoldhouse.com. 4 March 2002.

- ^ C. Lynn: Wallpaper in America from the Seventeenth Century to World War I (New York, 1980)