WWT Slimbridge

| WWT Slimbridge | |

|---|---|

Slimbridge has numerous nene (also known as Hawaiian geese), the rarest goose in the world. | |

| OS grid | SO720048 |

| Coordinates | 51°44′29″N 2°24′22″W / 51.741471°N 2.405979°W |

| Area | 120 acres (49 ha) |

| Operated by | WWT |

| Status | Open |

| Website | www |

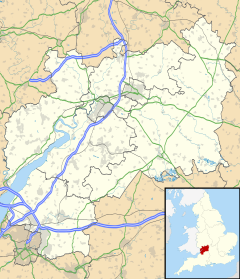

WWT Slimbridge is a wetland wildlife reserve near Slimbridge in Gloucestershire, England. It is midway between Bristol and Gloucester on the eastern side of the estuary of the River Severn. The reserve, set up by the artist and naturalist Sir Peter Scott, opened in November 1946. Scott subsequently founded the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, which has since opened nine other reserves around the country. Slimbridge comprises some 800 hectares (2,000 acres) of pasture, reed bed, lagoon and salt marsh. Many water birds live there all year round, and others are migrants on their ways to and from their summer breeding grounds. Other birds overwinter, including large numbers of white-fronted geese and increasing numbers of Bewick's swans.

Besides having the world's largest collection of captive wildfowl, Slimbridge takes part in research and is involved in projects and internationally run captive breeding programmes. It was there that Peter Scott developed a method of recognising individual birds through their characteristics, after realising that the coloured patterns on the beaks of Bewick's swans were unique. The public can visit the reserve throughout the year. Besides examining the collections, they can view birds from hides and observatories and take part in educational activities.

History

The Wildlife and Wetland Trust at Slimbridge was set up by Peter Scott and opened on 10 November 1946, as a centre for research and conservation. In a move unusual at the time, he opened the site to the public so that everyone could enjoy access to nature.[1][2]

This modest beginning developed in time into the formation of the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust, the only United Kingdom charity to promote the protection of wetland birds and their habitats, both in Britain and internationally.[3] Although starting out at Slimbridge, the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust now owns or manages nine other reserves in Britain,[4] and advocates for wetlands and conservation issues world-wide. WWT Consulting is an offshoot of the Wildlife & Wetland Trust and is based at Slimbridge. It provides ecological surveys and assessments, and offers consultancy services in wetland habitat design, wetland management, biological waste-water treatment systems and the management of reserves and their visitor centres.[5] The Queen in later years became Patron to the WWT, and Prince Charles became the President.[6]

A bust of founder Sir Peter Scott by Jacqueline Shackleton was completed in 1986 and is on display in the grounds.[7] His wife Philippa, Lady Scott, sat for Jon Edgar as part of his Environmental Series of heads, and a bronze was unveiled in the visitor centre in December 2011.[8] A sculpture by Peter Scott's mother, Kathleen Scott, entitled: Here Am I, Send Me, originally commissioned for West Downs Preparatory School, is also on display in the grounds.[7][9]

Site

The site consists of 800 hectares (2,000 acres) of reserve,[10] of which part is landscaped and can be visited by the public. At Slimbridge is the largest collection of wildfowl species in the world, and wild birds mingle with these in the enclosures.[10] Some of the captive birds form part of international breeding programmes. The reserve includes a mixture of pastureland, much of which gets flooded in winter, lagoons, reed beds and salt marshes besides the Severn Estuary. Many wildfowl visit the site including greater white-fronted geese, Eurasian spoonbills, pied avocets and even common cranes, the latter being birds that were originally bred here and later released on the Somerset Levels. There are also some rare species of plant on the reserve including the grass-poly (Lythrum hyssopifolia) and the wasp orchid, a variant of the bee orchid (Ophrys apifera).[4]

The number of ducks, geese and swans is greatest in winter, with large flocks of greater white-fronted geese, sometimes with a rare lesser white-fronted goose amongst them. Bewick's swans are a feature of Slimbridge in winter, arriving from northern Russia to enjoy the milder climate of southern England.[2] Their behaviour has been studied intensively at Slimbridge. Birds of prey such as peregrine and merlin also visit the centre in the winter, as well as wading birds and some woodland birds, and it is a good place to see the elusive water rail.[10]

Species present all year round include little and great crested grebes, lapwing, redshank, tufted duck, gadwall, kingfisher, reed bunting, great spotted woodpecker, sparrowhawk and little owl. In the spring, passage waders visit the pools alongside the estuary; these include Eurasian whimbrel, common, wood and green sandpipers, spotted redshank, common greenshank, avocet, little gull and black tern, and other migrants arriving at the reserve include northern wheatear, whinchat, common redstart and black redstart.[10]

Swans and geese usually start to arrive in late October. Passage waders in the autumn include red knot, black-tailed godwit, dunlin, ringed and grey plovers, ruff, common greenshank, spotted redshank, curlew sandpiper and common, wood and green sandpipers. Besides Bewick's swan and flocks of white-fronted geese, large waterfowl regularly present in the reserve in winter include the brent goose, pink-footed goose, barnacle goose and taiga bean goose. The swans tend to fly off in the day and return to feed in the late afternoon, and another spectacular sight at the end of winter afternoons is the arrival of large flocks of starlings. Smaller wildfowl present in winter include wigeon, Eurasian teal, common pochard, northern pintail, water rail, dunlin, redshank, curlew, golden plover, common snipe and ruff.[10]

Projects

Before the establishment of the WWT reserve at Slimbridge, no Bewick's swans were regularly wintering on the Severn Estuary. In 1948, one arrived at Slimbridge, perhaps attracted by a captive whistling swan. A mate for this bird was acquired from the Netherlands and the pair eventually successfully bred. More wild Bewick's swans joined the group so that by 1964, more than thirty wild swans were present. So that the birds could be better studied, the tame resident swans were relocated to an easily observable lake. Peter Scott realised that every bird had a unique patterning of black and yellow on its beak by which individual birds could be recognised. These were recorded in small paintings with front and side views (rather like "mug shots") to aid recognition. By 1989, over six thousand swans had been recorded visiting the site, and by this means, much research was made possible on the birds.[11]

An early success story in the 1950s was the saving of the nene (or Hawaiian goose) from extinction.[1] Birds were brought to the site and breeding at Slimbridge was successful. Initial releases into the wild in Hawaii were a failure however, because the nene's natural habitat was not protected from the predators that had been introduced to the islands by man. Once that problem was alleviated, successful reintroduction became possible.[12]

During Princess Elizabeth's 1951 tour of Canada, she was promised a Dominion gift of trumpeter swans, the arrangements to be made by Peter Scott.[13] Canadian officials discovered the only swans tame enough to capture were at Lonesome Lake in British Columbia as they had been fed for decades by conservationist Ralph Edwards.[13] In 1952, with the help of Ralph and his daughter Trudy, five were captured and flown to England, the first time trumpeter swans had ever flown across the Atlantic (although in the 19th century swans had been brought by ship to European zoos).[13] One unfortunately died, but the remaining four thrived at WWT Slimbridge for many years.[13]

Slimbridge has also been involved in trying to increase population levels of common cranes, which had bred spasmodically in Britain since the late 1970s. A specially built "Crane School" is used where the young birds are taught to forage and avoid danger. This project has led to 23 birds being released onto the Somerset Moors and Levels in September 2013,[14] and 93 being released by the end of 2015.[15]

In September 2016, a researcher from Slimbridge is planning to become a "human swan" and follow migrating Bewick's swans using a powered paraglider.[16] She plans to try to find out the hazards they face during migration and why their numbers have halved in the last twenty years. The 4,500 mi (7,200 km) mission from the Arctic tundra of Russia to Slimbridge is expected to last for ten weeks.[17]

Facilities

The Sloane Observation Tower gives far-reaching views to the Cotswold escarpment in the east and the River Severn and Forest of Dean in the West. The £6.2m visitor centre has a shop, waterside restaurant, cinema, art gallery and tropical house, and exhibitions are held in the "Hanson Discovery Centre".[10] There are sixteen hides[18] that visitors can use for bird watching, as well as several comfortable observatories. Educational visits are available for schools and there is a programme of guided walks, events, talks and workshops.[2]

Visitors are allowed to feed the captive birds with approved food mixes bought on site, and during the winter, feeding of wild birds near one of the hides takes place at certain scheduled times, including on some floodlit occasions in the evening for visiting groups.[18]

References

- ^ a b "History of WWT". Wildfowl & Wetland Trust. Archived from the original on 7 September 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ a b c "WWT Slimbridge Wetland Centre". Cotswolds.info. Archived from the original on 5 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ Bell, Catharine E. (2001). Encyclopedia of the World's Zoos. Taylor & Francis. p. 1331. ISBN 978-1-57958-174-9. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ a b "Our nature reserves: Slimbridge". WWT. Archived from the original on 21 August 2016. Retrieved 21 August 2016.

- ^ "WWT Consulting". Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (Consulting) Ltd. Archived from the original on 31 August 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ "Royal support for drains that "work with nature"". Latest from WWT. WWT. 19 May 2015. Archived from the original on 21 September 2016. Retrieved 20 August 2016.

- ^ a b "Panoramic tour of Kathleen Scott Sculpture, WWT Slimbridge". CleVR. 11 October 2006. Archived from the original on 20 April 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2013.

- ^ Edgar, Jon (2008). Responses – Carvings and Claywork – Jon Edgar Sculpture 2003–2008. Hesworth Press. ISBN 978-0-9558675-0-7.

- ^ Stocker, Mark (2013). "'Young male objects': the ideal sculpture of Kathleen Scott". Sculpture Journal. 22 (2): 119–127. doi:10.3828/sj.2013.20d.

- ^ a b c d e f Tipling, David (2006). Where to Watch Birds in Britain and Ireland: Slimbridge. New Holland Publishers. pp. 62–63. ISBN 978-1-84537-459-4.

- ^ Bell, Catharine E. (2001). Encyclopedia of the World's Zoos. Taylor & Francis. pp. 1186–1187. ISBN 978-1-57958-174-9. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ Kear, Janet; Berger, A.J (2010). The Hawaiian Goose. A&C Black. pp. 79–114. ISBN 978-1-4081-3758-1. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

- ^ a b c d Leland Stowe (1957). Crusoe of Lonesome Lake, Victor Gollancz, Ltd, London, 1958. Chapter 14: "The Saga of the Trumpeter Swans", pg.162–178.

- ^ "Cranes fighting fit and ready for release". Birdwatch. 23 August 2013. Archived from the original on 17 September 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ "The Great Crane Project". Archived from the original on 1 October 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ McKie, Robin (4 September 2016). ""Human swan" conservationist takes to skies on 4,600-mile migration". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ^ "'Human swan' Sacha Dench to join 4,500-mile migration". BBC News. 26 April 2016. Archived from the original on 17 October 2016. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ^ a b Newsome, David; Kingston, Ross; Moore, Susan A. (2005). Wildlife Tourism. Channel View Publications. p. 345. ISBN 978-1-84541-316-3. Archived from the original on 18 August 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2016.

External links

![]() Media related to WWT Slimbridge at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to WWT Slimbridge at Wikimedia Commons