Villa of Trajan

The Villa of Trajan[1] was a palatial summer residence and hunting lodge of the ancient Roman Emperor Trajan (r. 98-117 AD), dating from the beginning of his reign. Its location, near the modern village of Arcinazzo, was, like many patrician villas, carefully chosen on high plateau at the foot of Monte Altuino (1271 m) and in a splendid wooded landscape to escape the summer heat of Rome. It is 2 km from the river Aniene which supplied Rome with water and on which Nero's villa at Subiaco is located about 12 km downstream. It occupies an area of about 5 hectares, much of which has yet to be excavated.[2] Many fine room decorations have been recovered here, despite the mass robbing of expensive marbles in previous centuries.

Pliny the Younger, in a laudatory oration delivered in 100 AD in Trajan's honour, described the surrounding landscape of the villa and speaks of his interests, especially fishing and hunting there:[3]

"...what other relaxation do you in fact allow yourself if not to walk the wooded slopes, drive wild beasts from their dens, overcome immense crests of mountains, climb summits covered with ice without anyone to lend you help and open the way and, in the meantime, go into the woods sacred in devout recollection and venerate the deities? (…). He works hard to find and capture wild beasts and his greatest and most welcome work consists in ferreting them out"

Site

The Villa was built on two large terraced platforms on the lower slopes of Monte Altuino, the lower terrace being the only one excavated to date.[4] The lower terrace is the "public" wing, used for visitors and entertainment, while the upper terrace is considered to be the "private" or residential wing.

Lower terrace

The lower terrace is a long rectangle (100 x 40 m) supported by a wall with massive buttresses, the cladding of which is in opus mixtum of brick latticework.

In the centre of the terrace is the garden, one of the focal points of the entire complex, surrounded by a peristyle and onto which face many rooms. At each end of the garden were two large semicircular basins with fountains and steps at the corners, entirely covered with slabs of white marble; both were flanked by a masonry base which perhaps supported a basin.[5]

To the west of the garden is the main building, the most imposing of the whole complex, and the one that has yielded the greatest number of finds of sumptuous stucco and marble decorations. The triclinium (summer dining room) (13 x 9 m) is in the centre, accessed by four doors spaced by large windows that open onto the side rooms. The entrance from the garden was framed by a pair of columns. On the back wall there is a nymphaeum consisting of three niches from which water poured into the pool below. The niches were framed by marble shelves, decorated with dolphins and tritons, on which were small columns supporting the decorated architrave. Above there was a mosaic band composed of glass-paste tesserae reflecting the sun's rays which, hitting the pool of water, created a play of light and colours on the surrounding walls in marble and stucco gold. The nymphaeum had an arch which created harmony and grace to the whole structure. The floor was decorated in colourful opus sectile, i.e. rectangular slabs of marble bordered by strips in giallo antico (antique yellow).

On both sides of the triclinium is a series of rooms of identical shape, size and function: first a large rectangular atrium (18 x 7.2 m), framed by a double pair of columns. The rooms at the back were intended for prestigious guests. These had two distinct entrances, one on each corner, placed on either side of the large window that overlooked the atrium-vestibule; the roof was a high barrel vault on massive brick pillars, while the floors were in opus sectile. The decoration of the walls (coloured marble and stucco) and the vault (frescoes) was extremely precious of which a large number of fragments have been found.[6]

The garden was surrounded on three sides (East-West-South) by arched and vaulted porticoes: to the South (long side towards the road) and to the East (one of the two short sides) columns are composed of brick half-columns covered with stucco. On the west side, however, the pillars were replaced by nine fluted columns and an architrave in cipollino marble on Ionic bases of white marble with wider intercolumns in the centre. The south portico constitutes the access corridor to the public wing, located in the western part of the terrace; the vault of this portico was decorated with continuous frescoes on a dark background with red ribs and a central oculus placed on the vertex, while the floor was covered in slabs of white marble. Evidence of this frescoed vault was the discovery of a substantial central portion of a clipeus depicting a Winged Victory, the deity who announced the outcome of battles, with sword and gold disc. To the south, along the road, the portico had large windows with a view over the magnificent landscape.

On the north side of the garden is the wall supporting the upper terrace, decorated by a succession of niches covered in marble from which water flowed. Shortly after the construction, however, these niches-fountains were walled up, probably due to their instability.

At the south-east corner an annex protruding towards the road is the vestibulum or main entrance of the villa from the via Praenestina below from which a staircase lead to the terrace.

The porticoes employed an architectural novelty, the flat arch, which allowed straight architraves to be used without expensive monolithic marble lintels.[7]

Stuccos

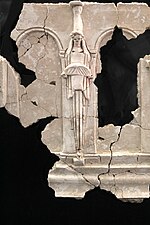

In monumental room XVIII overlooking the garden an enormous quantity of fragments of stuccos was found collapsed on the floor, clearly from the decorative band in the upper area of the walls and above the marble covering. They are of the highest artistic quality for the variety of subjects, execution technique and surface gilding, found only in imperial villas or those of patricians.

The stuccos were divided into rich bands decorated with geometric, floral or figurative motifs and panels with slender perspective architectures, within which are standing and seated figures of divinities. The architectural features stand out for the execution of details of the bases and pediments of the columns.[8]

Marbles

In addition to the more common marbles, African, cipollino, giallo antico, pavonazzetto, portasanta and various granites, porphyries and serpentines, breccia di Sciro and Egyptian black porphyry were used.[9]

Decorative Techniques

The transport and assembly of material and marble to this difficult and distant site from Rome was not an easy and inexpensive operation, only feasible with the imperial commission. Marbles from quarries in Italy and the African and Eastern provinces were often marked with engraved or red-painted inscriptions relating to the place of extraction and to the client.[10] The processing or finishing of the pieces took place on site: the assembly phases are documented by acronyms or numbers engraved on capitals, bases, shelves, to indicate the place where they were to be placed or were the initials of names; elsewhere were marks in black charcoal or drawings made by the workers, such as the donkey that appears on the reverse of a slab. An interesting graffiti, engraved with square and compasses, was discovered on a facing slab of room XIX depicting either a niche with an apsidal basin or the plan of an apsidal room.

Upper Terrace

A geophysical survey identified underlying structures of the upper terrace which was shown to be the private residential part of the villa, including thermal baths and an elliptical structure, probably a vivarium, a large tank for breeding fish.

Water supply

The Villa was fed by two large cisterns located at a higher level. One, on the north-east hill, consists of two long rectangular rooms with barrel vaults, connected by open passages in the central wall. The second cistern, the remains of which are incorporated in houses, stood to the west, closer to the upper terrace and was used to feed the fountains inside the Triclinium. All the outgoing water flowed outside through a tunnel that flows under a buttress of the terrace.

History of excavations

Trajan's Villa was plundered as early as the 5th and 6th centuries, testified by numerous piles of marble and building material, while rooms XIV and XXVI were used for a kitchen and a small forge. Further stripping took place during the 17th century due to the wealth and abundance of marble, of which the villa was a real mine.[11] Excavations in 1777 stand out at recovering marble for the construction of the church of Sant'Andrea near Subiaco. The correspondence between the director of the excavations, G. Corradi, and the Prefect of Antiquities of the Papal State, GB Visconti, shows that the supply of precious marbles was huge. In 1829-1833 there was further removal of material for the Church of Santa Maria Assunta near Arcinazzo Romano. The work was long, gradual and generalised and involved not only materials of high quality, but also humbler ones such as lead.

In 1955, 1958 and 1960 the first real excavation campaigns took place during which a small part of the Villa along via Sublacense was brought to light, the retaining wall delimiting the lower terrace and part of the similar one for the upper terrace, which showed the plan had a peristyle and what was then considered a nymphaeum (today identified with the triclinium).

Other limited excavations took place in the 1970s and between 1980 and 1982 which led to the important discovery of the triclinium. The most recent excavations were annually from 1999 with many finds of the splendid decoration and restoration of the areas already brought to light.

Identification

At the end of the 19th century a series of fistula acquaria (lead water pipes) were found near the villa bearing the imperial title and the name of the procurator, Hebrus, the same as for Trajan's villa at Centumcellae (today's Civitavecchia). This allowed the complex to be attributed with certainty to Trajan and also to fix its date. The following text is on the first series of fistulae:[12]

Imp(eratoris) Nervae Traiani Caesar(is) Aug(usti) Germanic(i) sub cura Hebri lib(erti) proc(uratoris): (Of the Emperor Nerva Trajan Caesar Augustus Germanicus, under the care of Hebrus, freedman and procurator)

This group can be dated between 97 AD and 99 AD because the epithet "Germanicus" was acquired after his victory in the wars against the Germans. On the second series is:[13]

Imp(eratoris) Caesaris Nervae Traiani Optimi Aug(usti) Germanic(i) Dacici: (Of the Emperor Caesar Nerva Trajan Optimus Augustus Germanicus Dacicus)

This group is dated 114-5 AD as the attribute "Dacicus" indicates his victory in the two Dacian wars in 106 AD, but the attribute "Parthicus" is not present, which he received only in 116 AD after victory over the Parthians.

In support of these dates are other archaeological data, such as the building technique in opus mixtum, typical of the Trajanic age.

References

- ^ Museo Villa di Traiano https://www.museovilladitraiano.it/

- ^ T. Cinti, M. Lo Castro, Arcinazzo Romano. Guida ai musei, Roma, 2011, p. 20

- ^ Pliny the Younger, Panegyric to Trajan, chap. 81, 1

- ^ T. Cinti, M. Lo Castro: The Archaeological Park and Museum of the Trajan Villa in Arcinazzo Romano

- ^ M. G. Fiore Cavaliere, Z. Mari, La Villa di Traiano ad Arcinazzo Romano. Guida alla lettura del territorio, Tivoli, 1999, p. 40

- ^ Mari 2015: Z. Mari, “The Marbles from the Villa of Trajan at Arcinazzo Romano (Rome)” in P. Pensabene, E.Gasparini (edited by) Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone, ASMOSIA X, International Conference (Rome, 2012) , Rome 2015

- ^ T. Cinti, M. Lo Castro: The Archaeological Park and Museum of the Trajan Villa in Arcinazzo Romano p 34

- ^ T. Cinti, M. Lo Castro: The Archaeological Park and Museum of the Trajan Villa in Arcinazzo Romano p 55

- ^ Mari 2015: Z. Mari, “The Marbles from the Villa of Trajan at Arcinazzo Romano (Rome)” in P. Pensabene, E.Gasparini (edited by) Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone, ASMOSIA X, International Conference (Rome, 2012), Rome 2015

- ^ Zaccaria Mari, La villa di Traiano ad Arcinazzo Romano, The Journal of Fasti Online, p 6, http://www.fastionline.org

- ^ Zaccaria Mari, La villa di Traiano ad Arcinazzo Romano, The Journal of Fasti Online, p 6, http://www.fastionline.org

- ^ CIL XVI 7893 a; 7893 b = AE 1892, 139; 7894

- ^ CIL XIV 3447 = CIL, XIV 7895 a1= AE 1892, 138)