Intelligence quotient

| Intelligence quotient | |

|---|---|

![[picture of an example IQ test item]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/ec/Raven_Matrix.svg/290px-Raven_Matrix.svg.png) One kind of IQ test item, modelled after items in the Raven's Progressive Matrices test | |

| ICD-10-PCS | Z01.8 |

| ICD-9-CM | 94.01 |

| Part of a series on |

| Psychology |

|---|

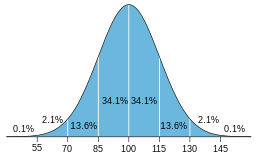

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a total score derived from a set of standardized tests or subtests designed to assess human intelligence.[1] Originally, IQ was a score obtained by dividing a person's mental age score, obtained by administering an intelligence test, by the person's chronological age, both expressed in terms of years and months. The resulting fraction (quotient) was multiplied by 100 to obtain the IQ score.[2] For modern IQ tests, the raw score is transformed to a normal distribution with mean 100 and standard deviation 15.[3] This results in approximately two-thirds of the population scoring between IQ 85 and IQ 115 and about 2 percent each above 130 and below 70.[4][5]

Scores from intelligence tests are estimates of intelligence. Unlike, for example, distance and mass, a concrete measure of intelligence cannot be achieved given the abstract nature of the concept of "intelligence".[6] IQ scores have been shown to be associated with such factors as nutrition,[7][8][9] parental socioeconomic status,[10][11] morbidity and mortality,[12][13] parental social status,[14] and perinatal environment.[15] While the heritability of IQ has been investigated for nearly a century, there is still debate about the significance of heritability estimates[16][17] and the mechanisms of inheritance.[18]

IQ scores are used for educational placement, assessment of intellectual ability, and evaluating job applicants. In research contexts, they have been studied as predictors of job performance[19] and income.[20] They are also used to study distributions of psychometric intelligence in populations and the correlations between it and other variables. Raw scores on IQ tests for many populations have been rising at an average rate that scales to three IQ points per decade since the early 20th century, a phenomenon called the Flynn effect. Investigation of different patterns of increases in subtest scores can also inform current research on human intelligence.

Historically, many proponents of IQ testing have been eugenicists who used pseudoscience to push now-debunked views of racial hierarchy in order to justify segregation and oppose immigration.[21][22] Such views are now rejected by a strong consensus of mainstream science, though fringe figures continue to promote them in pseudo-scholarship and popular culture.[23][24]

History

Precursors to IQ testing

Historically, even before IQ tests were devised, there were attempts to classify people into intelligence categories by observing their behavior in daily life.[25][26] Those other forms of behavioral observation are still important for validating classifications based primarily on IQ test scores. Both intelligence classification by observation of behavior outside the testing room and classification by IQ testing depend on the definition of "intelligence" used in a particular case and on the reliability and error of estimation in the classification procedure.

The English statistician Francis Galton (1822–1911) made the first attempt at creating a standardized test for rating a person's intelligence. A pioneer of psychometrics and the application of statistical methods to the study of human diversity and the study of inheritance of human traits, he believed that intelligence was largely a product of heredity (by which he did not mean genes, although he did develop several pre-Mendelian theories of particulate inheritance).[27][28][29] He hypothesized that there should exist a correlation between intelligence and other observable traits such as reflexes, muscle grip, and head size.[30] He set up the first mental testing center in the world in 1882 and he published "Inquiries into Human Faculty and Its Development" in 1883, in which he set out his theories. After gathering data on a variety of physical variables, he was unable to show any such correlation, and he eventually abandoned this research.[31][32]

French psychologist Alfred Binet and psychiatrist Théodore Simon, had more success in 1905, when they published the Binet–Simon Intelligence test, which focused on verbal abilities.[33] It was intended to identify "mental retardation" in school children,[34] but in specific contradistinction to claims made by psychiatrists that these children were "sick" (not "slow") and should therefore be removed from school and cared for in asylums.[33] The score on the Binet–Simon scale would reveal the child's mental age. For example, a six-year-old child who passed all the tasks usually passed by six-year-olds—but nothing beyond—would have a mental age that matched his chronological age, 6.0. (Fancher, 1985). Binet and Simon thought that intelligence was multifaceted, but came under the control of practical judgment.

In Binet and Simon's view, there were limitations with the scale and they stressed what they saw as the remarkable diversity of intelligence and the subsequent need to study it using qualitative, as opposed to quantitative, measures (White, 2000). American psychologist Henry H. Goddard published a translation of it in 1910. American psychologist Lewis Terman at Stanford University revised the Binet–Simon scale, which resulted in the Stanford revision of the Binet-Simon Intelligence Scale (1916). It became the most popular test in the United States for decades.[34][35][36][37]

The abbreviation "IQ" was coined by the psychologist William Stern for the German term Intelligenzquotient, his term for a scoring method for intelligence tests at University of Breslau he advocated in a 1912 book.[38]

General factor (g)

The many different kinds of IQ tests include a wide variety of item content. Some test items are visual, while many are verbal. Test items vary from being based on abstract-reasoning problems to concentrating on arithmetic, vocabulary, or general knowledge.

The British psychologist Charles Spearman in 1904 made the first formal factor analysis of correlations between the tests. He observed that children's school grades across seemingly unrelated school subjects were positively correlated, and reasoned that these correlations reflected the influence of an underlying general mental ability that entered into performance on all kinds of mental tests. He suggested that all mental performance could be conceptualized in terms of a single general ability factor and a large number of narrow task-specific ability factors. Spearman named it g for "general factor" and labeled the specific factors or abilities for specific tasks s.[39] In any collection of test items that make up an IQ test, the score that best measures g is the composite score that has the highest correlations with all the item scores. Typically, the "g-loaded" composite score of an IQ test battery appears to involve a common strength in abstract reasoning across the test's item content.[citation needed]

United States military selection in World War I

During World War I, the Army needed a way to evaluate and assign recruits to appropriate tasks. This led to the development of several mental tests by Robert Yerkes, who worked with major hereditarians of American psychometrics—including Terman, Goddard—to write the test.[40] The testing generated controversy and much public debate in the United States. Nonverbal or "performance" tests were developed for those who could not speak English or were suspected of malingering.[34] Based on Goddard's translation of the Binet–Simon test, the tests had an impact in screening men for officer training:

...the tests did have a strong impact in some areas, particularly in screening men for officer training. At the start of the war, the army and national guard maintained nine thousand officers. By the end, two hundred thousand officers presided, and two- thirds of them had started their careers in training camps where the tests were applied. In some camps, no man scoring below C could be considered for officer training.[40]

In total 1.75 million men were tested, making the results the first mass-produced written tests of intelligence, though considered dubious and non-usable, for reasons including high variability of test implementation throughout different camps and questions testing for familiarity with American culture rather than intelligence.[40] After the war, positive publicity promoted by army psychologists helped to make psychology a respected field.[41] Subsequently, there was an increase in jobs and funding in psychology in the United States.[42] Group intelligence tests were developed and became widely used in schools and industry.[43]

The results of these tests, which at the time reaffirmed contemporary racism and nationalism, are considered controversial and dubious, having rested on certain contested assumptions: that intelligence was heritable, innate, and could be relegated to a single number, the tests were enacted systematically, and test questions actually tested for innate intelligence rather than subsuming environmental factors.[40] The tests also allowed for the bolstering of jingoist narratives in the context of increased immigration, which may have influenced the passing of the Immigration Restriction Act of 1924.[40]

L.L. Thurstone argued for a model of intelligence that included seven unrelated factors (verbal comprehension, word fluency, number facility, spatial visualization, associative memory, perceptual speed, reasoning, and induction). While not widely used, Thurstone's model influenced later theories.[34]

David Wechsler produced the first version of his test in 1939. It gradually became more popular and overtook the Stanford–Binet in the 1960s. It has been revised several times, as is common for IQ tests, to incorporate new research. One explanation is that psychologists and educators wanted more information than the single score from the Binet. Wechsler's ten or more subtests provided this. Another is that the Stanford–Binet test reflected mostly verbal abilities, while the Wechsler test also reflected nonverbal abilities. The Stanford–Binet has also been revised several times and is now similar to the Wechsler in several aspects, but the Wechsler continues to be the most popular test in the United States.[34]

IQ testing and the eugenics movement in the United States

Eugenics, a set of beliefs and practices aimed at improving the genetic quality of the human population by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior and promoting those judged to be superior,[44][45][46] played a significant role in the history and culture of the United States during the Progressive Era, from the late 19th century until US involvement in World War II.[47][48]

The American eugenics movement was rooted in the biological determinist ideas of the British Scientist Sir Francis Galton. In 1883, Galton first used the word eugenics to describe the biological improvement of human genes and the concept of being "well-born".[49][50] He believed that differences in a person's ability were acquired primarily through genetics and that eugenics could be implemented through selective breeding in order for the human race to improve in its overall quality, therefore allowing for humans to direct their own evolution.[51]

Henry H. Goddard was a eugenicist. In 1908, he published his own version, The Binet and Simon Test of Intellectual Capacity, and cordially promoted the test. He quickly extended the use of the scale to the public schools (1913), to immigration (Ellis Island, 1914) and to a court of law (1914).[52]

Unlike Galton, who promoted eugenics through selective breeding for positive traits, Goddard went with the US eugenics movement to eliminate "undesirable" traits.[53] Goddard used the term "feeble-minded" to refer to people who did not perform well on the test. He argued that "feeble-mindedness" was caused by heredity, and thus feeble-minded people should be prevented from giving birth, either by institutional isolation or sterilization surgeries.[52] At first, sterilization targeted the disabled, but was later extended to poor people. Goddard's intelligence test was endorsed by the eugenicists to push for laws for forced sterilization. Different states adopted the sterilization laws at different paces. These laws, whose constitutionality was upheld by the Supreme Court in their 1927 ruling Buck v. Bell, forced over 60,000 people to go through sterilization in the United States.[54]

California's sterilization program was so effective that the Nazis turned to the government for advice on how to prevent the birth of the "unfit".[55] While the US eugenics movement lost much of its momentum in the 1940s in view of the horrors of Nazi Germany, advocates of eugenics (including Nazi geneticist Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer) continued to work and promote their ideas in the United States.[55] In later decades, some eugenic principles have made a resurgence as a voluntary means of selective reproduction, with some calling them "new eugenics".[56] As it becomes possible to test for and correlate genes with IQ (and its proxies),[57] ethicists and embryonic genetic testing companies are attempting to understand the ways in which the technology can be ethically deployed.[58]

Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory

Raymond Cattell (1941) proposed two types of cognitive abilities in a revision of Spearman's concept of general intelligence. Fluid intelligence (Gf) was hypothesized as the ability to solve novel problems by using reasoning, and crystallized intelligence (Gc) was hypothesized as a knowledge-based ability that was very dependent on education and experience. In addition, fluid intelligence was hypothesized to decline with age, while crystallized intelligence was largely resistant to the effects of aging. The theory was almost forgotten, but was revived by his student John L. Horn (1966) who later argued Gf and Gc were only two among several factors, and who eventually identified nine or ten broad abilities. The theory continued to be called Gf-Gc theory.[34]

John B. Carroll (1993), after a comprehensive reanalysis of earlier data, proposed the three stratum theory, which is a hierarchical model with three levels. The bottom stratum consists of narrow abilities that are highly specialized (e.g., induction, spelling ability). The second stratum consists of broad abilities. Carroll identified eight second-stratum abilities. Carroll accepted Spearman's concept of general intelligence, for the most part, as a representation of the uppermost, third stratum.[59][60]

In 1999, a merging of the Gf-Gc theory of Cattell and Horn with Carroll's Three-Stratum theory has led to the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory (CHC Theory), with g as the top of the hierarchy, ten broad abilities below, and further subdivided into seventy narrow abilities on the third stratum. CHC Theory has greatly influenced many of the current broad IQ tests.[34]

Modern tests do not necessarily measure all of these broad abilities. For example, quantitative knowledge and reading and writing ability may be seen as measures of school achievement and not IQ.[34] Decision speed may be difficult to measure without special equipment. g was earlier often subdivided into only Gf and Gc, which were thought to correspond to the nonverbal or performance subtests and verbal subtests in earlier versions of the popular Wechsler IQ test. More recent research has shown the situation to be more complex.[34] Modern comprehensive IQ tests do not stop at reporting a single IQ score. Although they still give an overall score, they now also give scores for many of these more restricted abilities, identifying particular strengths and weaknesses of an individual.[34]

Other theories

An alternative to standard IQ tests, meant to test the proximal development of children, originated in the writings of psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) during his last two years of his life.[61][62] According to Vygotsky, the maximum level of complexity and difficulty of problems that a child is capable to solve under some guidance indicates their level of potential development. The difference between this level of potential and the lower level of unassisted performance indicates the child's zone of proximal development.[63] Combination of the two indexes—the level of actual and the zone of the proximal development—according to Vygotsky, provides a significantly more informative indicator of psychological development than the assessment of the level of actual development alone.[64][65] His ideas on the zone of development were later developed in a number of psychological and educational theories and practices, most notably under the banner of dynamic assessment, which seeks to measure developmental potential[66][67][68] (for instance, in the work of Reuven Feuerstein and his associates,[69] who has criticized standard IQ testing for its putative assumption or acceptance of "fixed and immutable" characteristics of intelligence or cognitive functioning). Dynamic assessment has been further elaborated in the work of Ann Brown, and John D. Bransford and in theories of multiple intelligences authored by Howard Gardner and Robert Sternberg.[70][71]

J.P. Guilford's Structure of Intellect (1967) model of intelligence used three dimensions, which, when combined, yielded a total of 120 types of intelligence. It was popular in the 1970s and early 1980s, but faded owing to both practical problems and theoretical criticisms.[34]

Alexander Luria's earlier work on neuropsychological processes led to the PASS theory (1997). It argued that only looking at one general factor was inadequate for researchers and clinicians who worked with learning disabilities, attention disorders, intellectual disability, and interventions for such disabilities. The PASS model covers four kinds of processes (planning process, attention/arousal process, simultaneous processing, and successive processing). The planning processes involve decision making, problem solving, and performing activities and require goal setting and self-monitoring.

The attention/arousal process involves selectively attending to a particular stimulus, ignoring distractions, and maintaining vigilance. Simultaneous processing involves the integration of stimuli into a group and requires the observation of relationships. Successive processing involves the integration of stimuli into serial order. The planning and attention/arousal components comes from structures located in the frontal lobe, and the simultaneous and successive processes come from structures located in the posterior region of the cortex.[72][73][74] It has influenced some recent IQ tests, and been seen as a complement to the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory described above.[34]

Current tests

There are a variety of individually administered IQ tests in use in the English-speaking world.[75][76][77] The most commonly used individual IQ test series is the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) for adults and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC) for school-age test-takers. Other commonly used individual IQ tests (some of which do not label their standard scores as "IQ" scores) include the current versions of the Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales, Woodcock–Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities, the Kaufman Assessment Battery for Children, the Cognitive Assessment System, and the Differential Ability Scales.

There are various other IQ tests, including:

- Raven's Progressive Matrices (RPM)

- Cattell Culture Fair III (CFIT)

- Reynolds Intellectual Assessment Scales (RIAS)

- Thurstone's Primary Mental Abilities[78][79]

- Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (KBIT)[80]

- Multidimensional Aptitude Battery II

- Das–Naglieri cognitive assessment system (CAS)

- Naglieri Nonverbal Ability Test (NNAT)

- Wide Range Intelligence Test (WRIT)

IQ scales are ordinally scaled.[81][82][83][84][85] The raw score of the norming sample is usually (rank order) transformed to a normal distribution with mean 100 and standard deviation 15.[3] While one standard deviation is 15 points, and two SDs are 30 points, and so on, this does not imply that mental ability is linearly related to IQ, such that IQ 50 would mean half the cognitive ability of IQ 100. In particular, IQ points are not percentage points.

Reliability and validity

Reliability

| Pupil | KABC-II | WISC-III | WJ-III |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 90 | 95 | 111 |

| B | 125 | 110 | 105 |

| C | 100 | 93 | 101 |

| D | 116 | 127 | 118 |

| E | 93 | 105 | 93 |

| F | 106 | 105 | 105 |

| G | 95 | 100 | 90 |

| H | 112 | 113 | 103 |

| I | 104 | 96 | 97 |

| J | 101 | 99 | 86 |

| K | 81 | 78 | 75 |

| L | 116 | 124 | 102 |

Psychometricians generally regard IQ tests as having high statistical reliability.[14][88] Reliability represents the measurement consistency of a test.[89] A reliable test produces similar scores upon repetition.[89] On aggregate, IQ tests exhibit high reliability, although test-takers may have varying scores when taking the same test on differing occasions, and may have varying scores when taking different IQ tests at the same age. Like all statistical quantities, any particular estimate of IQ has an associated standard error that measures uncertainty about the estimate. For modern tests, the confidence interval can be approximately 10 points and reported standard error of measurement can be as low as about three points.[90] Reported standard error may be an underestimate, as it does not account for all sources of error.[91]

Outside influences such as low motivation or high anxiety can occasionally lower a person's IQ test score.[89] For individuals with very low scores, the 95% confidence interval may be greater than 40 points, potentially complicating the accuracy of diagnoses of intellectual disability.[92] By the same token, high IQ scores are also significantly less reliable than those near to the population median.[93] Reports of IQ scores much higher than 160 are considered dubious.[94]

Validity as a measure of intelligence

Reliability and validity are very different concepts. While reliability reflects reproducibility, validity refers to whether the test measures what it purports to measure.[89] While IQ tests are generally considered to measure some forms of intelligence, they may fail to serve as an accurate measure of broader definitions of human intelligence inclusive of, for example, creativity and social intelligence. For this reason, psychologist Wayne Weiten argues that their construct validity must be carefully qualified, and not be overstated.[89] According to Weiten, "IQ tests are valid measures of the kind of intelligence necessary to do well in academic work. But if the purpose is to assess intelligence in a broader sense, the validity of IQ tests is questionable."[89]

Some scientists have disputed the value of IQ as a measure of intelligence altogether. In The Mismeasure of Man (1981, expanded edition 1996), evolutionary biologist Stephen Jay Gould compared IQ testing with the now-discredited practice of determining intelligence via craniometry, arguing that both are based on the fallacy of reification, "our tendency to convert abstract concepts into entities".[95] Gould's argument sparked a great deal of debate,[96][97] and the book is listed as one of Discover Magazine's "25 Greatest Science Books of All Time".[98]

Along these same lines, critics such as Keith Stanovich do not dispute the capacity of IQ test scores to predict some kinds of achievement, but argue that basing a concept of intelligence on IQ test scores alone neglects other important aspects of mental ability.[14][99] Robert Sternberg, another significant critic of IQ as the main measure of human cognitive abilities, argued that reducing the concept of intelligence to the measure of g does not fully account for the different skills and knowledge types that produce success in human society.[100]

Despite these objections, clinical psychologists generally regard IQ scores as having sufficient statistical validity for many clinical purposes.[specify][34][101]

Test bias or differential item functioning

Differential item functioning (DIF), sometimes referred to as measurement bias, is a phenomenon when participants from different groups (e.g. gender, race, disability) with the same latent abilities give different answers to specific questions on the same IQ test.[102] DIF analysis measures such specific items on a test alongside measuring participants' latent abilities on other similar questions. A consistent different group response to a specific question among similar types of questions can indicate an effect of DIF. It does not count as differential item functioning if both groups have an equally valid chance of giving different responses to the same questions. Such bias can be a result of culture, educational level and other factors that are independent of group traits. DIF is only considered if test-takers from different groups with the same underlying latent ability level have a different chance of giving specific responses.[103] Such questions are usually removed in order to make the test equally fair for both groups. Common techniques for analyzing DIF are item response theory (IRT) based methods, Mantel-Haenszel, and logistic regression.[103]

A 2005 study found that "differential validity in prediction suggests that the WAIS-R test may contain cultural influences that reduce the validity of the WAIS-R as a measure of cognitive ability for Mexican American students,"[104] indicating a weaker positive correlation relative to sampled white students. Other recent studies have questioned the culture-fairness of IQ tests when used in South Africa.[105][106] Standard intelligence tests, such as the Stanford–Binet, are often inappropriate for autistic children; the alternative of using developmental or adaptive skills measures are relatively poor measures of intelligence in autistic children, and may have resulted in incorrect claims that a majority of autistic children are of low intelligence.[107]

Flynn effect

Since the early 20th century, raw scores on IQ tests have increased in most parts of the world.[108][109][110] When a new version of an IQ test is normed, the standard scoring is set so performance at the population median results in a score of IQ 100. The phenomenon of rising raw score performance means if test-takers are scored by a constant standard scoring rule, IQ test scores have been rising at an average rate of around three IQ points per decade. This phenomenon was named the Flynn effect in the book The Bell Curve after James R. Flynn, the author who did the most to bring this phenomenon to the attention of psychologists.[111][112]

Researchers have been exploring the issue of whether the Flynn effect is equally strong on performance of all kinds of IQ test items, whether the effect may have ended in some developed nations, whether there are social subgroup differences in the effect, and what possible causes of the effect might be.[113] A 2011 textbook, IQ and Human Intelligence, by N. J. Mackintosh, noted the Flynn effect demolishes the fears that IQ would be decreased. He also asks whether it represents a real increase in intelligence beyond IQ scores.[114] A 2011 psychology textbook, lead authored by Harvard Psychologist Professor Daniel Schacter, noted that humans' inherited intelligence could be going down while acquired intelligence goes up.[115]

Research has suggested that the Flynn effect has slowed or reversed course in some Western countries beginning in the late 20th century. The phenomenon has been termed the negative Flynn effect.[116] A study of Norwegian military conscripts' test records found that IQ scores have been falling for generations born after the year 1975, and that the underlying cause of both initial increasing and subsequent falling trends appears to be environmental rather than genetic.[116]

Age

Ronald S. Wilson is largely credited with the idea that IQ heritability rises with age.[117] Researchers building on this phenomenon dubbed it "The Wilson Effect," named after the behavioral geneticist.[118] A paper by Thomas J. Bouchard Jr., examining twin and adoption studies, including twins "reared apart," finds that IQ "reaches an asymptote at about 0.80 at 18–20 years of age and continuing at that level well into adulthood. In the aggregate, the studies also confirm that shared environmental influence decreases across age, approximating about 0.10 at 18–20 years of age and continuing at that level into adulthood."[118] IQ can change to some degree over the course of childhood.[119] In one longitudinal study, the mean IQ scores of tests at ages 17 and 18 were correlated at r = 0.86 with the mean scores of tests at ages five, six, and seven and at r = 0.96[further explanation needed] with the mean scores of tests at ages 11, 12, and 13.[14]

The current consensus is that fluid intelligence generally declines with age after early adulthood, while crystallized intelligence remains intact.[120] However, the exact peak age of fluid intelligence or crystallized intelligence remains elusive. Cross-sectional studies usually show that especially fluid intelligence peaks at a relatively young age (often in the early adulthood) while longitudinal data mostly show that intelligence is stable until mid-adulthood or later. Subsequently, intelligence seems to decline slowly.[121]

For decades, practitioners' handbooks and textbooks on IQ testing have reported IQ declines with age after the beginning of adulthood. However, later researchers pointed out this phenomenon is related to the Flynn effect and is in part a cohort effect rather than a true aging effect. A variety of studies of IQ and aging have been conducted since the norming of the first Wechsler Intelligence Scale drew attention to IQ differences in different age groups of adults. Both cohort effects (the birth year of the test-takers) and practice effects (test-takers taking the same form of IQ test more than once) must be controlled to gain accurate data.[inconsistent] It is unclear whether any lifestyle intervention can preserve fluid intelligence into older ages.[120]

Genetics and environment

Environmental and genetic factors play a role in determining IQ. Their relative importance has been the subject of much research and debate.[122]

Heritability

The general figure for the heritability of IQ, according to an American Psychological Association report, is 0.45 for children, and rises to around 0.75 for late adolescents and adults.[14] Heritability measures for g factor in infancy are as low as 0.2, around 0.4 in middle childhood, and as high as 0.9 in adulthood.[123][124] One proposed explanation is that people with different genes tend to reinforce the effects of those genes, for example by seeking out different environments.[14][125]

Shared family environment

Family members have aspects of environments in common (for example, characteristics of the home). This shared family environment accounts for 0.25–0.35 of the variation in IQ in childhood. By late adolescence, it is quite low (zero in some studies). The effect for several other psychological traits is similar. These studies have not looked at the effects of extreme environments, such as in abusive families.[14][126][127][128]

Non-shared family environment and environment outside the family

Although parents treat their children differently, such differential treatment explains only a small amount of nonshared environmental influence. One suggestion is that children react differently to the same environment because of different genes. More likely influences may be the impact of peers and other experiences outside the family.[14][127]

Individual genes

A very large proportion of the over 17,000 human genes are thought to have an effect on the development and functionality of the brain.[129] While a number of individual genes have been reported to be associated with IQ, none have a strong effect. Deary and colleagues (2009) reported that no finding of a strong single gene effect on IQ has been replicated.[130] Recent findings of gene associations with normally varying intellectual differences in adults and children continue to show weak effects for any one gene.[131][132]

A 2017 meta-analysis conducted on approximately 78,000 subjects identified 52 genes associated with intelligence.[133] FNBP1L is reported to be the single gene most associated with both adult and child intelligence.[134]

Gene-environment interaction

David Rowe reported an interaction of genetic effects with socioeconomic status, such that the heritability was high in high-SES families, but much lower in low-SES families.[135] In the US, this has been replicated in infants,[136] children,[137] adolescents,[138] and adults.[139] Outside the US, studies show no link between heritability and SES.[140] Some effects may even reverse sign outside the US.[140][141]

Dickens and Flynn (2001) have argued that genes for high IQ initiate an environment-shaping feedback cycle, with genetic effects causing bright children to seek out more stimulating environments that then further increase their IQ. In Dickens' model, environment effects are modeled as decaying over time. In this model, the Flynn effect can be explained by an increase in environmental stimulation independent of it being sought out by individuals. The authors suggest that programs aiming to increase IQ would be most likely to produce long-term IQ gains if they enduringly raised children's drive to seek out cognitively demanding experiences.[142][143]

Interventions

In general, educational interventions, as those described below, have shown short-term effects on IQ, but long-term follow-up is often missing. For example, in the US, very large intervention programs such as the Head Start Program have not produced lasting gains in IQ scores. Even when students improve their scores on standardized tests, they do not always improve their cognitive abilities, such as memory, attention and speed.[144] More intensive, but much smaller projects, such as the Abecedarian Project, have reported lasting effects, often on socioeconomic status variables, rather than IQ.[14]

Recent studies have shown that training in using one's working memory may increase IQ. A study on young adults published in April 2008 by a team from the Universities of Michigan and Bern supports the possibility of the transfer of fluid intelligence from specifically designed working memory training.[145] Further research will be needed to determine nature, extent and duration of the proposed transfer. Among other questions, it remains to be seen whether the results extend to other kinds of fluid intelligence tests than the matrix test used in the study, and if so, whether, after training, fluid intelligence measures retain their correlation with educational and occupational achievement or if the value of fluid intelligence for predicting performance on other tasks changes. It is also unclear whether the training is durable for extended periods of time.[146]

Music

Musical training in childhood correlates with higher than average IQ.[147][148] However, a study of 10,500 twins found no effects on IQ, suggesting that the correlation was caused by genetic confounders.[149] A meta-analysis concluded that "Music training does not reliably enhance children and young adolescents' cognitive or academic skills, and that previous positive findings were probably due to confounding variables."[150]

It is popularly thought that listening to classical music raises IQ. However, multiple attempted replications (e.g.[151]) have shown that this is at best a short-term effect (lasting no longer than 10 to 15 minutes), and is not related to IQ-increase.[152]

Brain anatomy

Several neurophysiological factors have been correlated with intelligence in humans, including the ratio of brain weight to body weight and the size, shape, and activity level of different parts of the brain. Specific features that may affect IQ include the size and shape of the frontal lobes, the amount of blood and chemical activity in the frontal lobes, the total amount of gray matter in the brain, the overall thickness of the cortex, and the glucose metabolic rate.[153]

Health

Health is important in understanding differences in IQ test scores and other measures of cognitive ability. Several factors can lead to significant cognitive impairment, particularly if they occur during pregnancy and childhood when the brain is growing and the blood–brain barrier is less effective. Such impairment may sometimes be permanent, or sometimes be partially or wholly compensated for by later growth.[154]

Since about 2010, researchers such as Eppig, Hassel, and MacKenzie have found a very close and consistent link between IQ scores and infectious diseases, especially in the infant and preschool populations and the mothers of these children.[155] They have postulated that fighting infectious diseases strains the child's metabolism and prevents full brain development. Hassel postulated that it is by far the most important factor in determining population IQ. However, they also found that subsequent factors such as good nutrition and regular quality schooling can offset early negative effects to some extent.

Developed nations have implemented several health policies regarding nutrients and toxins known to influence cognitive function. These include laws requiring fortification of certain food products[156] and laws establishing safe levels of pollutants (e.g. lead, mercury, and organochlorides). Improvements in nutrition, and in public policy in general, have been implicated in IQ increases.[157]

Cognitive epidemiology is a field of research that examines the associations between intelligence test scores and health. Researchers in the field argue that intelligence measured at an early age is an important predictor of later health and mortality differences.[13]

Social correlations

School performance

The American Psychological Association's report Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns states that wherever it has been studied, children with high scores on tests of intelligence tend to learn more of what is taught in school than their lower-scoring peers. The correlation between IQ scores and grades is about .50. This means that the explained variance is 25%. Achieving good grades depends on many factors other than IQ, such as "persistence, interest in school, and willingness to study" (p. 81).[14]

It has been found that the correlation of IQ scores with school performance depends on the IQ measurement used. For undergraduate students, the Verbal IQ as measured by WAIS-R has been found to correlate significantly (0.53) with the grade point average (GPA) of the last 60 hours (credits). In contrast, Performance IQ correlation with the same GPA was only 0.22 in the same study.[158]

Some measures of educational aptitude correlate highly with IQ tests – for instance, Frey & Detterman (2004) reported a correlation of 0.82 between g (general intelligence factor) and SAT scores;[159] another research found a correlation of 0.81 between g and GCSE scores, with the explained variance ranging "from 58.6% in Mathematics and 48% in English to 18.1% in Art and Design".[160]

Job performance

According to Schmidt and Hunter, "for hiring employees without previous experience in the job the most valid predictor of future performance is general mental ability."[19] The validity of IQ as a predictor of job performance is above zero for all work studied to date, but varies with the type of job and across different studies, ranging from 0.2 to 0.6.[161] The correlations were higher when the unreliability of measurement methods was controlled for.[14] While IQ is more strongly correlated with reasoning and less so with motor function,[162] IQ-test scores predict performance ratings in all occupations.[19]

That said, for highly qualified activities (research, management) low IQ scores are more likely to be a barrier to adequate performance, whereas for minimally-skilled activities, athletic strength (manual strength, speed, stamina, and coordination) is more likely to influence performance.[19] The prevailing view among academics is that it is largely through the quicker acquisition of job-relevant knowledge that higher IQ mediates job performance. This view has been challenged by Byington & Felps (2010), who argued that "the current applications of IQ-reflective tests allow individuals with high IQ scores to receive greater access to developmental resources, enabling them to acquire additional capabilities over time, and ultimately perform their jobs better."[163]

Newer studies find that the effects of IQ on job performance have been greatly overestimated. The current estimates of the correlation between job performance and IQ are about 0.23 correcting for unreliability and range restriction.[164][165]

In establishing a causal direction to the link between IQ and work performance, longitudinal studies by Watkins and others suggest that IQ exerts a causal influence on future academic achievement, whereas academic achievement does not substantially influence future IQ scores.[166] Treena Eileen Rohde and Lee Anne Thompson write that general cognitive ability, but not specific ability scores, predict academic achievement, with the exception that processing speed and spatial ability predict performance on the SAT math beyond the effect of general cognitive ability.[167]

However, large-scale longitudinal studies indicate an increase in IQ translates into an increase in performance at all levels of IQ: i.e. ability and job performance are monotonically linked at all IQ levels.[168][169]

Income

It has been suggested that "in economic terms it appears that the IQ score measures something with decreasing marginal value" and it "is important to have enough of it, but having lots and lots does not buy you that much".[170][171]

The link from IQ to wealth is much less strong than that from IQ to job performance. Some studies indicate that IQ is unrelated to net worth.[172][173] The American Psychological Association's 1995 report Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns stated that IQ scores accounted for about a quarter of the social status variance and one-sixth of the income variance. Statistical controls for parental SES eliminate about a quarter of this predictive power. Psychometric intelligence appears as only one of a great many factors that influence social outcomes.[14] Charles Murray (1998) showed a more substantial effect of IQ on income independent of family background.[174] In a meta-analysis, Strenze (2006) reviewed much of the literature and estimated the correlation between IQ and income to be about 0.23.[20]

Some studies assert that IQ only accounts for (explains) a sixth of the variation in income because many studies are based on young adults, many of whom have not yet reached their peak earning capacity, or even their education. On pg 568 of The g Factor, Arthur Jensen says that although the correlation between IQ and income averages a moderate 0.4 (one-sixth or 16% of the variance), the relationship increases with age, and peaks at middle age when people have reached their maximum career potential. In the book, A Question of Intelligence, Daniel Seligman cites an IQ income correlation of 0.5 (25% of the variance).

A 2002 study further examined the impact of non-IQ factors on income and concluded that an individual's location, inherited wealth, race, and schooling are more important as factors in determining income than IQ.[175]

Crime

The American Psychological Association's 1995 report Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns stated that the correlation between IQ and crime was −0.2. This association is generally regarded as small and prone to disappearance or a substantial reduction after controlling for the proper covariates, being much smaller than typical sociological correlates.[176] It was −0.19 between IQ scores and the number of juvenile offenses in a large Danish sample; with social class controlled for, the correlation dropped to −0.17. A correlation of 0.20 means that the explained variance accounts for 4% of the total variance. The causal links between psychometric ability and social outcomes may be indirect. Children with poor scholastic performance may feel alienated. Consequently, they may be more likely to engage in delinquent behavior, compared to other children who do well.[14]

In his book The g Factor (1998), Arthur Jensen cited data which showed that, regardless of race, people with IQs between 70 and 90 have higher crime rates than people with IQs below or above this range, with the peak range being between 80 and 90.

The 2009 Handbook of Crime Correlates stated that reviews have found that around eight IQ points, or 0.5 SD, separate criminals from the general population, especially for persistent serious offenders. It has been suggested that this simply reflects that "only dumb ones get caught" but there is similarly a negative relation between IQ and self-reported offending. That children with conduct disorder have lower IQ than their peers "strongly argues" for the theory.[177]

A study of the relationship between US county-level IQ and US county-level crime rates found that higher average IQs were very weakly associated with lower levels of property crime, burglary, larceny rate, motor vehicle theft, violent crime, robbery, and aggravated assault. These results were "not confounded by a measure of concentrated disadvantage that captures the effects of race, poverty, and other social disadvantages of the county."[178] However, this study is limited in that it extrapolated Add Health estimates to the respondent's counties, and as the dataset was not designed to be representative on the state or county level, it may not be generalizable.[179]

It has also been shown that the effect of IQ is heavily dependent on socioeconomic status and that it cannot be easily controlled away, with many methodological considerations being at play.[180] Indeed, there is evidence that the small relationship is mediated by well-being, substance abuse, and other confounding factors that prohibit simple causal interpretation.[181] A recent meta-analysis has shown that the relationship is only observed in higher risk populations such as those in poverty without direct effect, but without any causal interpretation.[182] A nationally representative longitudinal study has shown that this relationship is entirely mediated by school performance.[183]

Health and mortality

Multiple studies conducted in Scotland have found that higher IQs in early life are associated with lower mortality and morbidity rates later in life.[184][185]

Other accomplishments

| Accomplishment | IQ | Test/study | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDs, JDs, and PhDs | 125 | WAIS-R | 1987 |

| College graduates | 112 | KAIT | 2000 |

| K-BIT | 1992 | ||

| 115 | WAIS-R | ||

| 1–3 years of college | 104 | KAIT | |

| K-BIT | |||

| 105–110 | WAIS-R | ||

| Clerical and sales workers | 100–105 | ||

| High school graduates, skilled workers (e.g., electricians, cabinetmakers) | 100 | KAIT | |

| WAIS-R | |||

| 97 | K-BIT | ||

| 1–3 years of high school (completed 9–11 years of school) | 94 | KAIT | |

| 90 | K-BIT | ||

| 95 | WAIS-R | ||

| Semi-skilled workers (e.g. truck drivers, factory workers) | 90–95 | ||

| Elementary school graduates (completed eighth grade) | 90 | ||

| Elementary school dropouts (completed 0–7 years of school) | 80–85 | ||

| Have 50/50 chance of reaching high school | 75 |

| Accomplishment | IQ | Test/study | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professional and technical | 112 | ||

| Managers and administrators | 104 | ||

| Clerical workers, sales workers, skilled workers, craftsmen, and foremen | 101 | ||

| Semi-skilled workers (operatives, service workers, including private household) | 92 | ||

| Unskilled workers | 87 |

| Accomplishment | IQ | Test/study | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults can harvest vegetables, repair furniture | 60 | ||

| Adults can do domestic work | 50 |

There is considerable variation within and overlap among these categories. People with high IQs are found at all levels of education and occupational categories. The biggest difference occurs for low IQs with only an occasional college graduate or professional scoring below 90.[34]

Group differences

Among the most controversial issues related to the study of intelligence is the observation that IQ scores vary on average between ethnic and racial groups, though these differences have fluctuated and in many cases steadily decreased over time.[189] While there is little scholarly debate about the continued existence of some of these differences, the current scientific consensus is that they stem from environmental rather than genetic causes.[190][191][192] The existence of differences in IQ between the sexes has been debated, and largely depends on which tests are performed.[193][194]

Race

While the concept of "race" is a social construct,[195] discussions of a purported relationship between race and intelligence, as well as claims of genetic differences in intelligence along racial lines, have appeared in both popular science and academic research since the modern concept of race was first introduced.

Genetics do not explain differences in IQ test performance between racial or ethnic groups.[23][190][191][192] Despite the tremendous amount of research done on the topic, no scientific evidence has emerged that the average IQ scores of different population groups can be attributed to genetic differences between those groups.[196][197][198] In recent decades, as understanding of human genetics has advanced, claims of inherent differences in intelligence between races have been broadly rejected by scientists on both theoretical and empirical grounds.[199][192][200][201][197]

Growing evidence indicates that environmental factors, not genetic ones, explain the racial IQ gap.[201][199][192] A 1996 task force investigation on intelligence sponsored by the American Psychological Association concluded that "because ethnic differences in intelligence reflect complex patterns, no overall generalization about them is appropriate," with environmental factors the most plausible reason for the shrinking gap.[14] A systematic analysis by William Dickens and James Flynn (2006) showed the gap between black and white Americans to have closed dramatically during the period between 1972 and 2002, suggesting that, in their words, the "constancy of the Black–White IQ gap is a myth".[202] The effects of stereotype threat have been proposed as an explanation for differences in IQ test performance between racial groups,[203][204] as have issues related to cultural difference and access to education.[205][206]

Despite the strong scientific consensus to the contrary, fringe figures continue to promote scientific racism about group-level IQ averages in pseudo-scholarship and popular culture.[23][24][21]

Sex

With the advent of the concept of g or general intelligence, many researchers have found that there are no significant sex differences in average IQ,[194][207][208] though ability in particular types of intelligence does vary.[193][208] Thus, while some test batteries show slightly greater intelligence in males, others show greater intelligence in females.[193][208] In particular, studies have shown female subjects performing better on tasks related to verbal ability,[194] and males performing better on tasks related to rotation of objects in space, often categorized as spatial ability.[209] These differences remain, as Hunt (2011) observes, "even though men and women are essentially equal in general intelligence".

Some research indicates that male advantages on some cognitive tests are minimized when controlling for socioeconomic factors.[193][207] Other research has concluded that there is slightly larger variability in male scores in certain areas compared to female scores, which results in slightly more males than females in the top and bottom of the IQ distribution.[210]

The existence of differences between male and female performance on math-related tests is contested,[211] and a meta-analysis focusing on average gender differences in math performance found nearly identical performance for boys and girls.[212] Currently, most IQ tests, including popular batteries such as the WAIS and the WISC-R, are constructed so that there are no overall score differences between females and males.[14][213][214]

Public policy

In the United States, certain public policies and laws regarding military service,[215][216] education, public benefits,[217] capital punishment,[110] and employment incorporate an individual's IQ into their decisions. However, in the case of Griggs v. Duke Power Co. in 1971, for the purpose of minimizing employment practices that disparately impacted racial minorities, the U.S. Supreme Court banned the use of IQ tests in employment, except when linked to job performance via a job analysis. Internationally, certain public policies, such as improving nutrition and prohibiting neurotoxins, have as one of their goals raising, or preventing a decline in, intelligence.

A diagnosis of intellectual disability is in part based on the results of IQ testing. Borderline intellectual functioning is the categorization of individuals of below-average cognitive ability (an IQ of 71–85), although not as low as those with an intellectual disability (70 or below).

In the United Kingdom, the eleven plus exam which incorporated an intelligence test has been used from 1945 to decide, at eleven years of age, which type of school a child should go to. They have been much less used since the widespread introduction of comprehensive schools.

Classification

IQ classification is the practice used by IQ test publishers for designating IQ score ranges into various categories with labels such as "superior" or "average".[187] IQ classification was preceded historically by attempts to classify human beings by general ability based on other forms of behavioral observation. Those other forms of behavioral observation are still important for validating classifications based on IQ tests.

High-IQ societies

There are social organizations, some international, which limit membership to people who have scores as high as or higher than the 98th percentile (two standard deviations above the mean) on some IQ test or equivalent. Mensa International is perhaps the best known of these. The largest 99.9th percentile (three standard deviations above the mean) society is the Triple Nine Society.

See also

- Emotional competence

- Emotional intelligence (EI), also known as emotional quotient (EQ) and emotional intelligence quotient (EIQ)

- Raven's Progressive Matrices

- Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scales

- Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale

- Woodcock–Johnson Tests of Cognitive Abilities

Citations

- ^ Braaten, Ellen B.; Norman, Dennis (1 November 2006). "Intelligence (IQ) Testing". Pediatrics in Review. 27 (11): 403–408. doi:10.1542/pir.27-11-403. ISSN 0191-9601. PMID 17079505. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ "intelligence quotient (IQ)". Glossary of Important Assessment and Measurement Terms. Philadelphia, PA: National Council on Measurement in Education. 2016. Archived from the original on 22 July 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ a b Gottfredson 2009, pp. 31–32

- ^ Neisser, Ulrich (1997). "Rising Scores on Intelligence Tests". American Scientist. 85 (5): 440–447. Bibcode:1997AmSci..85..440N. Archived from the original on 4 November 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ Hunt 2011, p. 5 "As mental testing expanded to the evaluation of adolescents and adults, however, there was a need for a measure of intelligence that did not depend upon mental age. Accordingly the intelligence quotient (IQ) was developed. ... The narrow definition of IQ is a score on an intelligence test ... where 'average' intelligence, that is the median level of performance on an intelligence test, receives a score of 100, and other scores are assigned so that the scores are distributed normally about 100, with a standard deviation of 15. Some of the implications are that: 1. Approximately two-thirds of all scores lie between 85 and 115. 2. Five percent (1/20) of all scores are above 125, and one percent (1/100) are above 135. Similarly, five percent are below 75 and one percent below 65."

- ^ Haier, Richard (28 December 2016). The Neuroscience of Intelligence. Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–19. ISBN 9781107461437.

- ^ Cusick, Sarah E.; Georgieff, Michael K. (1 August 2017). "The Role of Nutrition in Brain Development: The Golden Opportunity of the 'First 1000 Days'". The Journal of Pediatrics. 175: 16–21. doi:10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.013. ISSN 0022-3476. PMC 4981537. PMID 27266965.

- ^ Saloojee, Haroon; Pettifor, John M (15 December 2001). "Iron deficiency and impaired child development". British Medical Journal. 323 (7326): 1377–1378. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7326.1377. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 1121846. PMID 11744547.

- ^ Qian, Ming; Wang, Dong; Watkins, William E.; Gebski, Val; Yan, Yu Qin; Li, Mu; Chen, Zu Pei (2005). "The effects of iodine on intelligence in children: a meta-analysis of studies conducted in China". Asia Pacific Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 14 (1): 32–42. ISSN 0964-7058. PMID 15734706.

- ^ Poh, Bee Koon; Lee, Shoo Thien; Yeo, Giin Shang; Tang, Kean Choon; Noor Afifah, Ab Rahim; Siti Hanisa, Awal; Parikh, Panam; Wong, Jyh Eiin; Ng, Alvin Lai Oon; SEANUTS Study Group (13 June 2019). "Low socioeconomic status and severe obesity are linked to poor cognitive performance in Malaysian children". BMC Public Health. 19 (Suppl 4): 541. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-6856-4. ISSN 1471-2458. PMC 6565598. PMID 31196019.

- ^ Galván, Marcos; Uauy, Ricardo; Corvalán, Camila; López-Rodríguez, Guadalupe; Kain, Juliana (September 2013). "Determinants of cognitive development of low SES children in Chile: a post-transitional country with rising childhood obesity rates". Maternal and Child Health Journal. 17 (7): 1243–1251. doi:10.1007/s10995-012-1121-9. ISSN 1573-6628. PMID 22915146. S2CID 19767926.

- ^ Markus Jokela; G. David Batty; Ian J. Deary; Catharine R. Gale; Mika Kivimäki (2009). "Low Childhood IQ and Early Adult Mortality: The Role of Explanatory Factors in the 1958 British Birth Cohort". Pediatrics. 124 (3): e380 – e388. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0334. PMID 19706576. S2CID 25256969.

- ^ a b Deary & Batty 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Neisser et al. 1995.

- ^ Ronfani, Luca; Vecchi Brumatti, Liza; Mariuz, Marika; Tognin, Veronica (2015). "The Complex Interaction between Home Environment, Socioeconomic Status, Maternal IQ and Early Child Neurocognitive Development: A Multivariate Analysis of Data Collected in a Newborn Cohort Study". PLOS ONE. 10 (5): e0127052. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1027052R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0127052. PMC 4440732. PMID 25996934.

- ^ Johnson, Wendy; Turkheimer, Eric; Gottesman, Irving I.; Bouchard, Thomas J. (August 2009). "Beyond Heritability". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 18 (4): 217–220. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01639.x. PMC 2899491. PMID 20625474.

- ^ Turkheimer 2008.

- ^ Devlin, B.; Daniels, Michael; Roeder, Kathryn (1997). "The heritability of IQ". Nature. 388 (6641): 468–71. Bibcode:1997Natur.388..468D. doi:10.1038/41319. PMID 9242404. S2CID 4313884.

- ^ a b c d Schmidt, Frank L.; Hunter, John E. (1998). "The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings" (PDF). Psychological Bulletin. 124 (2): 262–74. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.172.1733. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.262. S2CID 16429503. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2014. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ a b Strenze, Tarmo (September 2007). "Intelligence and socioeconomic success: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal research". Intelligence. 35 (5): 401–426. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2006.09.004.

The correlation with income is considerably lower, perhaps even disappointingly low, being about the average of the previous meta-analytic estimates (.15 by Bowles et al., 2001; and .27 by Ng et al., 2005). But...other predictors, studied in this paper, are not doing any better in predicting income, which demonstrates that financial success is difficult to predict by any variable. This assertion is further corroborated by the meta-analysis of Ng et al. (2005) where the best predictor of salary was educational level with a correlation of only .29. It should also be noted that the correlation of .23 is about the size of the average meta-analytic result in psychology(Hemphill, 2003) and cannot, therefore, be treated as insignificant.

- ^ a b Winston, Andrew S. (29 May 2020). "Scientific Racism and North American Psychology". Oxford Research Encyclopedias: Psychology.

The use of psychological concepts and data to promote ideas of an enduring racial hierarchy dates from the late 1800s and has continued to the present. The history of scientific racism in psychology is intertwined with broader debates, anxieties, and political issues in American society. With the rise of intelligence testing, joined with ideas of eugenic progress and dysgenic reproduction, psychological concepts and data came to play an important role in naturalizing racial inequality. Although racial comparisons were not the primary concern of most early mental testing, results were employed to justify beliefs regarding Black "educability" and the dangers of Southern and Eastern European immigration.

- ^ Newitz, Annalee (4 June 2024). "Chapter 4". Stories Are Weapons: Psychological Warfare and the American Mind. W. W. Norton & Company.

- ^ a b c Bird, Kevin; Jackson, John P.; Winston, Andrew S. (2024). "Confronting Scientific Racism in Psychology: Lessons from Evolutionary Biology and Genetics". American Psychologist. 79 (4): 497–508. doi:10.1037/amp0001228. PMID 39037836.

Recent articles claim that the folk categories of race are genetically meaningful divisions, and that evolved genetic differences among races and nations are important for explaining immutable differences in cognitive ability, educational attainment, crime, sexual behavior, and wealth; all claims that are opposed by a strong scientific consensus to the contrary.

- ^ a b Panofsky, Aaron; Dasgupta, Kushan; Iturriaga, Nicole (2021). "How White nationalists mobilize genetics: From genetic ancestry and human biodiversity to counterscience and metapolitics". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 175 (2): 387–398. doi:10.1002/ajpa.24150. ISSN 0002-9483. PMC 9909835. PMID 32986847.

[T]he claims that genetics defines racial groups and makes them different, that IQ and cultural differences among racial groups are caused by genes, and that racial inequalities within and between nations are the inevitable outcome of long evolutionary processes are neither new nor supported by science (either old or new).

- ^ Terman 1916, p. 79 "What do the above IQ's imply in such terms as feeble-mindedness, border-line intelligence, dullness, normality, superior intelligence, genius, etc.? When we use these terms two facts must be born in mind: (1) That the boundary lines between such groups are absolutely arbitrary, a matter of definition only; and (2) that the individuals comprising one of the groups do not make up a homogeneous type."

- ^ Wechsler 1939, p. 37 "The earliest classifications of intelligence were very rough ones. To a large extent they were practical attempts to define various patterns of behavior in medical-legal terms."

- ^ Bulmer, M (1999). "The development of Francis Galton's ideas on the mechanism of heredity". Journal of the History of Biology. 32 (3): 263–292. doi:10.1023/a:1004608217247. PMID 11624207. S2CID 10451997.

- ^ Cowan, R. S. (1972). "Francis Galton's contribution to genetics". Journal of the History of Biology. 5 (2): 389–412. doi:10.1007/bf00346665. PMID 11610126. S2CID 30206332.

- ^ Burbridge, D (2001). "Francis Galton on twins, heredity and social class". British Journal for the History of Science. 34 (3): 323–340. doi:10.1017/s0007087401004332. PMID 11700679.

- ^ Fancher, R. E. (1983). "Biographical origins of Francis Galton's psychology". Isis. 74 (2): 227–233. doi:10.1086/353245. PMID 6347965. S2CID 40565053.

- ^ Kaufman 2009, p. 21 "Galton's so-called intelligence test was misnamed."

- ^ Gillham, Nicholas W. (2001). "Sir Francis Galton and the birth of eugenics". Annual Review of Genetics. 35 (1): 83–101. doi:10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.090055. PMID 11700278.

- ^ a b Nicolas, S.; Andrieu, B.; Croizet, J.-C.; Sanitioso, R. B.; Burman, J. T. (2013). "Sick? Or slow? On the origins of intelligence as a psychological object". Intelligence. 41 (5): 699–711. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2013.08.006. (This is an open access article, made freely available by Elsevier.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Kaufman 2009

- ^ Terman et al. 1915.

- ^ Wallin, J. E. W. (1911). "The new clinical psychology and the psycho-clinicist". Journal of Educational Psychology. 2 (3): 121–32. doi:10.1037/h0075544.

- ^ Richardson, John T. E. (2003). "Howard Andrew Knox and the origins of performance testing on Ellis Island, 1912-1916". History of Psychology. 6 (2): 143–70. doi:10.1037/1093-4510.6.2.143. PMID 12822554.

- ^ Stern 1914, pp. 70–84 (1914 English translation), pp. 48–58 (1912 original German edition).

- ^ Deary 2001, pp. 6–12.

- ^ a b c d e Gould 1996

- ^ Kennedy, Carrie H.; McNeil, Jeffrey A. (2006). "A history of military psychology". In Kennedy, Carrie H.; Zillmer, Eric (eds.). Military Psychology: Clinical and Operational Applications. New York: Guilford Press. pp. 1–17. ISBN 978-1-57230-724-7.

- ^ Katzell, Raymond A.; Austin, James T. (1992). "From then to now: The development of industrial-organizational psychology in the United States". Journal of Applied Psychology. 77 (6): 803–35. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.77.6.803.

- ^ Kevles, D. J. (1968). "Testing the Army's Intelligence: Psychologists and the Military in World War I". The Journal of American History. 55 (3): 565–81. doi:10.2307/1891014. JSTOR 1891014.

- ^ Spektorowski, Alberto; Ireni-Saban, Liza (2013). Politics of Eugenics: Productionism, Population, and National Welfare. London: Routledge. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-203-74023-1. Retrieved 16 January 2017.

As an applied science, thus, the practice of eugenics referred to everything from prenatal care for mothers to forced sterilization and euthanasia. Galton divided the practice of eugenics into two types—positive and negative—both aimed at improving the human race through selective breeding.

- ^ "Eugenics". Unified Medical Language System (Psychological Index Terms). National Library of Medicine. 26 September 2010.

- ^ Galton, Francis (July 1904). "Eugenics: Its Definition, Scope, and Aims". The American Journal of Sociology. X (1): 82, 1st paragraph. Bibcode:1904Natur..70...82.. doi:10.1038/070082a0. Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 27 December 2010.

Eugenics is the science which deals with all influences that improve the inborn qualities of a race; also with those that develop them to the utmost advantage.

- ^ Susan Currell; Christina Cogdell (2006). Popular Eugenics: National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in the 1930s. Ohio University Press. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-0-8214-1691-4.

- ^ "Eugenics and Economics in the Progressive Era" (PDF).

- ^ "Origins of Eugenics: From Sir Francis Galton to Virginia's Racial Integrity Act of 1924". University of Virginia: Historical Collections at the Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. Retrieved 25 October 2019.

- ^ Norrgard, K. (2008). "Human testing, the eugenics movement, and IRBs". Nature Education. 1: 170.

- ^ Galton, Francis (1869). "Hereditary Genius" (PDF). p. 64. Retrieved 1 October 2019.

- ^ a b "The birth of American intelligence testing". Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "America's Hidden History: The Eugenics Movement | Learn Science at Scitable". www.nature.com. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ "Social Origins of Eugenics". www.eugenicsarchive.org. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ a b "The Horrifying American Roots of Nazi Eugenics". hnn.us. September 2003. Retrieved 11 November 2017.

- ^ Vizcarrondo, Felipe E. (August 2014). "Human Enhancement: The New Eugenics". The Linacre Quarterly. 81 (3): 239–243. doi:10.1179/2050854914Y.0000000021. PMC 4135459. PMID 25249705.

- ^ Regalado, Antonio. "Eugenics 2.0: We're at the Dawn of Choosing Embryos by Health, Height, and More". Technology Review. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ LeMieux, Julianna (1 April 2019). "Polygenic Risk Scores and Genomic Prediction: Q&A with Stephen Hsu". Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News. Retrieved 20 November 2019.

- ^ Lubinski, David (2004). "Introduction to the Special Section on Cognitive Abilities: 100 Years After Spearman's (1904) "'General Intelligence,' Objectively Determined and Measured"". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 86 (1): 96–111. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.1.96. PMID 14717630. S2CID 6024297.

- ^ Carroll 1993, p. [page needed].

- ^ Mindes, Gayle (2003). Assessing Young Children. Merrill/Prentice Hall. p. 158. ISBN 9780130929082.

- ^ Haywood, H. Carl; Lidz, Carol S. (2006). Dynamic Assessment in Practice: Clinical and Educational Applications. Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 9781139462075.

- ^ Vygotsky, L.S. (1934). "The Problem of Age". The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky, Volume 5 (published 1998). pp. 187–205.

- ^ Chaiklin, S. (2003). "The Zone of Proximal Development in Vygotsky's analysis of learning and instruction". In Kozulin, A.; Gindis, B.; Ageyev, V.; Miller, S. (eds.). Vygotsky's educational theory and practice in cultural context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 39–64.

- ^ Zaretskii, V.K. (November–December 2009). "The Zone of Proximal Development What Vygotsky Did Not Have Time to Write". Journal of Russian and East European Psychology. 47 (6): 70–93. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405470604. S2CID 146894219.

- ^ Sternberg, R.S.; Grigorenko, E.L. (2001). "All testing is dynamic testing". Issues in Education. 7 (2): 137–170.

- ^ Sternberg, R.J. & Grigorenko, E.L. (2002). Dynamic testing: The nature and measurement of learning potential. Cambridge: University of Cambridge

- ^ Haywood & Lidz 2006, p. [page needed].

- ^ Feuerstein, R., Feuerstein, S., Falik, L & Rand, Y. (1979; 2002). Dynamic assessments of cognitive modifiability. ICELP Press, Jerusalem: Israel

- ^ Dodge, Kenneth A. (2006). Foreword. Dynamic Assessment in Practice: Clinical And Educational Applications. By Haywood, H. Carl; Lidz, Carol S. Cambridge University Press. pp. xiii–xv.

- ^ Kozulin, A. (2014). "Dynamic assessment in search of its identity". In Yasnitsky, A.; van der Veer, R.; Ferrari, M. (eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Cultural-Historical Psychology. Cambridge University Press. pp. 126–147.

- ^ Das, J.P.; Kirby, J.; Jarman, R.F. (1975). "Simultaneous and successive synthesis: An alternative model for cognitive abilities". Psychological Bulletin. 82: 87–103. doi:10.1037/h0076163.

- ^ Das, J.P. (2000). "A better look at intelligence". Current Directions in Psychological Science. 11: 28–33. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00162. S2CID 146129242.

- ^ Naglieri, J.A.; Das, J.P. (2002). "Planning, attention, simultaneous, and successive cognitive processes as a model for assessment". School Psychology Review. 19 (4): 423–442. doi:10.1080/02796015.1990.12087349.

- ^ Urbina 2011, Table 2.1 Major Examples of Current Intelligence Tests

- ^ Flanagan & Harrison 2012, chapters 8–13, 15–16 (discussing Wechsler, Stanford–Binet, Kaufman, Woodcock–Johnson, DAS, CAS, and RIAS tests)

- ^ Stanek, Kevin C.; Ones, Deniz S. (2018), "Taxonomies and Compendia of Cognitive Ability and Personality Constructs and Measures Relevant to Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology", The SAGE Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology: Personnel Psychology and Employee Performance, 1 Oliver's Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications Ltd, pp. 366–407, doi:10.4135/9781473914940.n14, ISBN 978-1-4462-0721-5, retrieved 8 January 2024

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Primary Mental Abilities Test | psychological test". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ "Defining and Measuring Psychological Attributes". homepages.rpi.edu. Archived from the original on 15 October 2018. Retrieved 26 November 2015.

- ^ Bain, Sherry K.; Jaspers, Kathryn E. (1 April 2010). "Test Review: Review of Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition Kaufman, A. S., & Kaufman, N. L. (2004). Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test, Second Edition. Bloomington, MN: Pearson, Inc". Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 28 (2): 167–174. doi:10.1177/0734282909348217. ISSN 0734-2829. S2CID 143961429.

- ^ Mussen, Paul Henry (1973). Psychology: An Introduction. Lexington, MA: Heath. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-669-61382-7.

The I.Q. is essentially a rank; there are no true "units" of intellectual ability.

- ^ Truch, Steve (1993). The WISC-III Companion: A Guide to Interpretation and Educational Intervention. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. p. 35. ISBN 978-0-89079-585-9.

An IQ score is not an equal-interval score, as is evident in Table A.4 in the WISC-III manual.

- ^ Bartholomew, David J. (2004). Measuring Intelligence: Facts and Fallacies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-521-54478-8.

When we come to quantities like IQ or g, as we are presently able to measure them, we shall see later that we have an even lower level of measurement—an ordinal level. This means that the numbers we assign to individuals can only be used to rank them—the number tells us where the individual comes in the rank order and nothing else.

- ^ Mackintosh 1998, pp. 30–31 "In the jargon of psychological measurement theory, IQ is an ordinal scale, where we are simply rank-ordering people. ... It is not even appropriate to claim that the 10-point difference between IQ scores of 110 and 100 is the same as the 10-point difference between IQs of 160 and 150"

- ^ Stevens, S. S. (1946). "On the Theory of Scales of Measurement". Science. 103 (2684): 677–680. Bibcode:1946Sci...103..677S. doi:10.1126/science.103.2684.677. PMID 17750512. S2CID 4667599.

- ^ Kaufman 2009, Figure 5.1 IQs earned by preadolescents (ages 12–13) who were given three different IQ tests in the early 2000s

- ^ Kaufman 2013, Figure 3.1 "Source: Kaufman (2009). Adapted with permission."

- ^ Mackintosh 2011, p. 169 "after the age of 8–10, IQ scores remain relatively stable: the correlation between IQ scores from age 8 to 18 and IQ at age 40 is over 0.70."

- ^ a b c d e f Weiten W (2016). Psychology: Themes and Variations. Cengage Learning. p. 281. ISBN 978-1305856127.

- ^ "WISC-V Interpretive Report Sample" (PDF). Pearson. p. 18. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 April 2022. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ Kaufman, Alan S.; Raiford, Susan Engi; Coalson, Diane L. (2016). Intelligent testing with the WISC-V. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley. pp. 683–702. ISBN 978-1-118-58923-6.

Reliability estimates in Table 4.1 and standard errors of measurement in Table 4.4 should be considered best-case estimates because they do not consider other major sources of error, such as transient error, administration error, or scoring error (Hanna, Bradley, & Holen, 1981), which influence test scores in clinical assessments. Another factor that must be considered is the extent to which subtest scores reflect portions of true score variance due to a hierarchical general intelligence factor and variance due to specific group factors because these sources of true score variance are conflated.

- ^ Whitaker, Simon (April 2010). "Error in the estimation of intellectual ability in the low range using the WISC-IV and WAIS-III". Personality and Individual Differences. 48 (5): 517–521. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2009.11.017. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ^ Lohman & Foley Nicpon 2012, p. [page needed]. "The concerns associated with SEMs [standard errors of measurement] are actually substantially worse for scores at the extremes of the distribution, especially when scores approach the maximum possible on a test ... when students answer most of the items correctly. In these cases, errors of measurement for scale scores will increase substantially at the extremes of the distribution. Commonly the SEM is from two to four times larger for very high scores than for scores near the mean (Lord, 1980)."

- ^ Urbina 2011, p. 20 "[Curve-fitting] is just one of the reasons to be suspicious of reported IQ scores much higher than 160"

- ^ Gould 1981, p. 24. Gould 1996, p. 56.

- ^ Kaplan, Jonathan Michael; Pigliucci, Massimo; Banta, Joshua Alexander (2015). "Gould on Morton, Redux: What can the debate reveal about the limits of data?" (PDF). Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences. 30: 1–10.

- ^ Weisberg, Michael; Paul, Diane B. (19 April 2016). "Morton, Gould, and Bias: A Comment on "The Mismeasure of Science"". PLOS Biology. 14 (4). e1002444. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1002444. ISSN 1544-9173. PMC 4836680. PMID 27092558.

- ^ "25 Greatest Science Books of All Time". Discover. 7 December 2006.

- ^ Brooks, David (14 September 2007). "The Waning of I.Q.". The New York Times.

- ^ Sternberg, Robert J., and Richard K. Wagner. "The g-ocentric view of intelligence and job performance is wrong." Current directions in psychological science (1993): 1–5.

- ^ Anastasi & Urbina 1997, pp. 326–327.

- ^ Embretson, S. E., Reise, S. P. (2000).Item Response Theory for Psychologists. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- ^ a b Zumbo, B.D. (2007). "Three generations of differential item functioning (DIF) analyses: Considering where it has been, where it is now, and where it is going". Language Assessment Quarterly. 4 (2): 223–233. doi:10.1080/15434300701375832. S2CID 17426415.