New York Central Railroad

| |

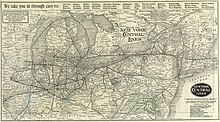

A map of the New York Central system in 1918 | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | New York Central Building, New York City |

| Key people | Cornelius Vanderbilt Owner (1867–1877) & President (1869–1877) Chauncey Depew President (1885–1898) & Chairman of the Board (1898–1928) |

| Founders | Erastus Corning John V. L. Pruyn Chauncey Vibbard |

| Reporting mark | NYC |

| Locale | Illinois Indiana Kentucky Massachusetts Michigan Missouri New Jersey New York Ohio Ontario Pennsylvania Quebec Vermont West Virginia |

| Dates of operation | May 17, 1853 – January 31, 1968 |

| Successor | Penn Central Transportation Company |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Length | 11,584 miles (18,643 km) (1926) |

The New York Central Railroad (reporting mark NYC) was a railroad primarily operating in the Great Lakes and Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The railroad primarily connected greater New York and Boston in the east with Chicago and St. Louis in the Midwest, along with the intermediate cities of Albany, Buffalo, Cleveland, Cincinnati, Detroit, Rochester and Syracuse. The New York Central was headquartered in the New York Central Building, adjacent to its largest station, Grand Central Terminal.

The railroad was established in 1853, consolidating several existing railroad companies. In 1968, the NYC merged with its former rival, the Pennsylvania Railroad, to form Penn Central.[1] Penn Central went into bankruptcy in 1970 and, with extensive Federal government support, emerged as Conrail in 1976.[2] In 1999, Conrail was broken-up, and portions of its system were transferred to CSX and Norfolk Southern Railway (NS), with CSX acquiring most of the NYC's eastern trackage and NS acquiring most of NYC's western trackage.

Extensive trackage existed in the states of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Indiana, Illinois, Massachusetts and West Virginia, plus additional trackage in portions of the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec. At the end of 1925, the New York Central Railroad operated 11,584 miles (18,643 km) of road and 26,395 miles (42,479 km) of track; at the end of 1967, the mileages were 9,696 miles (15,604 km) and 18,454 miles (29,699 km).[a]

Early history

Pre-New York Central: 1826–1853

Albany and Schenectady Railroad

The Mohawk and Hudson Railroad (M&H) was the oldest segment of the railroad's merger and was the first permanent railroad in the state of New York and one of the first railroads in the United States. It was chartered in 1826 to connect the Mohawk River at Schenectady, New York to the Hudson River at Albany, providing a way for freight and especially passengers to avoid the extensive and time-consuming locks on the Erie Canal between Schenectady and Albany, New York. The M&H opened on August 9, 1831, with its first steam locomotive, the Dewitt Clinton running on its tracks.[3][4] It would later change its name to the Albany and Schenectady (A&S) on April 19, 1847. Until the 1840s, it used an inclined planes at either end of the line to pull passenger cars up and down A&S' steep hills.[5] As locomotive technology progressed, the mainline was extended to the Mohawk River in downtown Schenectady and the Hudson River waterfront in Albany.[6]

Utica and Schenectady Railroad

The Utica and Schenectady Railroad was chartered April 29, 1833; as the railroad paralleled the Erie Canal, it was prohibited from carrying freight. Revenue service began on August 2, 1836, extending the line of the Albany and Schenectady Railroad west from Schenectady along the north side of the Mohawk River, paralleling the Erie Canal, to Utica. Of the ten early railroads bordering the Erie Canal, the U&S was the most profitable. It was headed by Erastus Corning, future president of the consolidated New York Central.[7] On May 7, 1844, the railroad was authorized to carry freight with some restrictions, and on May 12, 1847, the ban was fully dropped, but the company still had to pay the equivalent in canal tolls to the state.

Syracuse and Utica Railroad

The Syracuse and Utica Railroad was chartered on May 11, 1836, and similarly had to pay the state for any freight displaced from the canal.[7] The full line opened July 3, 1839, extending the line further to Syracuse via Rome (and further to Auburn via the already-opened Auburn and Syracuse Railroad). This line was not direct, going out of its way to stay near the Erie Canal and serve Rome, and so the Syracuse and Utica Direct Railroad was chartered on January 26, 1853. Nothing of that line was ever built, though the later West Shore Railroad, acquired by New York Central Railroad in 1885, served the same purpose.

Auburn and Syracuse Railroad

The Auburn and Syracuse Railroad was chartered on May 1, 1834, and opened mostly in 1838, the remaining 4 miles (6.4 km) opening on June 4, 1839. A month later, with the opening of the Syracuse and Utica Railroad, this formed a complete line from Albany west via Syracuse to Auburn. The Auburn and Rochester Railroad was chartered on May 13, 1836, as a further extension via Geneva and Canandaigua to Rochester, opening on November 4, 1841. The two lines merged on August 1, 1850, to form the rather indirect Rochester and Syracuse Railroad (known later as the Auburn Road). To fix this, the Rochester and Syracuse Direct Railway was chartered and immediately merged into the Rochester and Syracuse Railroad on August 6, 1850. That line opened June 1, 1853, running much more directly between those two cities, roughly parallel to the Erie Canal.

Buffalo and Rochester Railroad

The Tonawanda Railroad, to the west of Rochester, was chartered on April 24, 1832, to build from that city to Attica. The first section, from Rochester southwest to Batavia, opened May 5, 1837, and the rest of the line to Attica opened on January 8, 1843. The Attica and Buffalo Railroad was chartered in 1836 and opened on November 24, 1842, running from Buffalo southeast to Attica. When the Auburn and Rochester Railroad opened in 1841, there was no connection at Rochester to the Tonawanda Railroad, but with that exception there was now an all-rail line between Buffalo and Albany. On March 19, 1844, the Tonawanda Railroad was authorized to build the connection, and it opened later that year. The Albany and Schenectady Railroad bought all the baggage, mail and emigrant cars of the other railroads between Albany and Buffalo on February 17, 1848, and began operating through cars.

On December 7, 1850, the Tonawanda Railroad and Attica and Buffalo Railroad merged to form the Buffalo and Rochester Railroad. A new direct line opened from Buffalo east to Batavia on April 26, 1852, and the old line between Depew (east of Buffalo) and Attica was sold to the Buffalo and New York City Railroad on November 1. The line was added to the New York and Erie Railroad system and converted to the Erie's 6 ft (1,829 mm) broad gauge.

Schenectady and Troy Railroad

The Schenectady and Troy Railroad was chartered in 1836 and opened in 1842, providing another route between the Hudson River and Schenectady, with its Hudson River terminal at Troy.

Rochester, Lockport, and Niagara Falls Railroad

The Lockport and Niagara Falls Railroad was originally incorporated on April 24, 1834, to run from Lockport on the Erie Canal west to Niagara Falls; the line opened in 1838 and was sold on June 2, 1850. On December 14, 1850, it was reorganized as the Rochester, Lockport and Niagara Falls Railroad, and an extension east to Rochester opened on July 1, 1852. The railroad was consolidated into the New York Central Railroad under the act of 1853. A portion of the line is currently operated as the Falls Road Railroad.[8]

Buffalo and Lockport Railroad

The Buffalo and Lockport Railroad was chartered on April 27, 1852, to build a branch of the Rochester, Lockport and Niagara Falls from Lockport towards Buffalo. It opened in 1854, running from Lockport to Tonawanda, where it joined the Buffalo and Niagara Falls Railroad, opened in 1837, for the rest of the way to Buffalo.

Mohawk Valley Railroad

The Mohawk Valley Railroad was chartered on January 21, 1851, and reorganized on December 28, 1852, to build a railroad on the south side of the Mohawk River from Schenectady to Utica, next to the Erie Canal and opposite the Utica and Schenectady. The company didn't build a line before it was absorbed, though the West Shore Railroad was later built on that location.

Syracuse and Utica Direct Railroad

The Syracuse and Utica Direct Railroad was chartered in 1853 to rival the Syracuse and Utica Railroad by building a more direct route, reducing travel time by a half-hour. The company was merged before any line could be built.

1853 company formation

Albany industrialist and Mohawk Valley Railroad owner Erastus Corning managed to unite the above railroads together into one system, and on March 17, 1853, executives and stockholders of each company agreed to merge. The merger was approved by the state legislature on April 2 and, on May 17, 1853, the New York Central Railroad was formed.

Soon the Buffalo and State Line Railroad and Erie and North East Railroad converted to 4 ft 8+1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge from 6 ft (1,829 mm) broad gauge and connected directly with the railroad in Buffalo, providing a through route to Erie, Pennsylvania.

Erastus Corning years: 1853–1867

The Rochester and Lake Ontario Railroad was organized in 1852 and opened in fall 1853; it was leased to the Rochester, Lockport and Niagara Falls Railroad, which became part of New York Central Railroad, before opening. In 1855, it was merged into the railroad, providing a branch from Rochester north to Charlotte on Lake Ontario.

The Buffalo and Niagara Falls Railroad was also merged into the railroad in 1855. It had been chartered in 1834 and opened in 1837, providing a line between Buffalo and Niagara Falls. It was leased to New York Central Railroad in 1853.

Also in 1855 came the merger with the Lewiston Railroad, running from Niagara Falls north to Lewiston. It was chartered in 1836 and opened in 1837, without connections to other railroads. In 1854, a southern extension opened to the Buffalo and Niagara Falls Railroad and the line was leased to the railroad.

The Canandaigua and Niagara Falls Railroad was chartered in 1851. The first stage opened in 1853 from Canandaigua on the Auburn Road west to Batavia on the main line. A continuation west to North Tonawanda opened later that year and, in 1854, a section opened in Niagara Falls connecting it to the Niagara Falls Suspension Bridge. New York Central Railroad bought the company at bankruptcy in 1858 and reorganized it as the Niagara Bridge and Canandaigua Railroad, merging it into itself in 1890.

The Saratoga and Hudson River Railroad was chartered in 1864 and opened in 1866 as a branch of the railroad from Athens Junction, southeast of Schenectady, southeast and south to Athens on the west side of the Hudson River. On September 9, 1876, the company was merged into the railroad, but in 1876 the terminal at Athens burned down and the line was abandoned.

The primary repair shops were established in Corning's hometown of Albany along with a classification yard and livestock pens on 300 acres of land (known as West Albany). Facilities included locomotive shops, freight and passenger car shops, and roundhouse terminals. These were the New York Central's primary back shops until the end of steam in 1957.[9]

Hudson River Railroad

The Troy and Greenbush Railroad was chartered in 1845 and opened later that year, connecting Troy south to Greenbush (now Rensselaer) on the east side of the Hudson River. The Hudson River Railroad was chartered on May 12, 1846, to extend this line south to New York City; the full line opened on October 3, 1851. Prior to completion, on June 1, it leased the Troy and Greenbush.

Cornelius Vanderbilt obtained control of the Hudson River Railroad in 1864, soon after he bought the parallel New York and Harlem Railroad.

Along the line of the Hudson River Railroad, the West Side Line was built in 1934 in the borough of Manhattan as an elevated bypass of then-abandoned street running trackage on Tenth and Eleventh Avenues. The elevated section has since been abandoned, and the tunnel north of 35th Street is used only by Amtrak trains to New York Penn Station (all other trains use the Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad to reach the Harlem Line). The surviving sections of the West Side Line south of 34th Street reopened as the High Line, a linear park built between 2009 and 2014.

Heyday

Vanderbilt years: 1867–1954

In 1867, Cornelius Vanderbilt acquired control of the Albany to Buffalo-running New York Central Railroad, with the help of maneuverings related to the Hudson River Bridge in Albany. On November 1, 1869, he merged the railroad with his Hudson River Railroad to form the New York Central and Hudson River Railroad. This extended the system south from Albany along the east bank of the Hudson River to New York City, with the leased Troy and Greenbush Railroad running from Albany north to Troy.

Vanderbilt's other lines were operated as part of the railroad included the New York and Harlem Railroad, Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway, Canada Southern Railway, and Michigan Central Railroad.

The Spuyten Duyvil and Port Morris Railroad was chartered in 1869 and opened in 1871, providing a route on the north side of the Harlem River for trains along the Hudson River to head southeast to the New York and Harlem Railroad. Trains could head toward Grand Central Depot, built by NYC and opened in 1871, or to the freight facilities at Port Morris. From opening, it was leased by the NYC.

The Geneva and Lyons Railroad was organized in 1877 and opened in 1878, leased by the NYC from opening. This was a connection between Syracuse and Rochester, running from the main line at Lyons to the Auburn Road at Geneva. It was merged into the NYC in 1890.

In 1885, the New York, West Shore and Buffalo Railway, a competitor since 1883 with trackage along the west shore of the Hudson River and on to Buffalo closely paralleling the NYC, was taken over by the NYC as the West Shore Railroad and developed passenger, freight, and car float operations at Weehawken Terminal. The NYC assumed control of the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie and Boston and Albany Railroads in 1887 and 1900, respectively, with both roads remaining as independently-operating subsidiaries. William H. Newman, president of the New York Central lines, resigned in 1909.[10] Newman had been president since 1901, when he replaced Samuel R. Callaway (who had replaced Depew as president in 1898).[11]

In 1914, the operations of eleven subsidiaries were merged with the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad, re-forming the New York Central Railroad. From the beginning of the merger, the railroad was publicly referred to as the New York Central Lines. In the summer of 1935, the identification was changed to the New York Central System, that name being kept until the merger with the Pennsylvania Railroad in 1968.

The Cleveland, Cincinnati, Chicago and St. Louis Railway, also known as the Big Four, was formed on June 30, 1889, by the merger of the Cleveland, Columbus, Cincinnati and Indianapolis Railway, the Cincinnati, Indianapolis, St. Louis and Chicago Railway and the Indianapolis and St. Louis Railway. The following year, the company gained control of the former Indiana Bloomington and Western Railway. By 1906, the Big Four was itself acquired by the New York Central Railroad. It operated independently until 1930; it was then referred to as the Big Four Route. In 1930, New York Central Railroad acquired a 99-year lease of both Michigan Central and the ''Big Four'' (Cleveland, Chicago Cincinnati & St. Louis Railroad).[12]

The back shops at West Albany, New York were unable to keep up with repairs to rolling stock, so additional shops were established east of Buffalo at Depew (1892), Croton-on-Hudson (Harmon Shops, 1907), and Oak Grove, Pennsylvania (Avis Shops, 1902). The Harmon Shops were particularly important as locomotive power was switched out from steam to electric at that point as trains approached New York City.[13]

Topography

The generally level topography of the NYC system had a character distinctively different from the mountainous terrain of its archrival, the Pennsylvania Railroad. Most of its major routes, including New York to Chicago, followed rivers and had no significant grades other than West Albany Hill and the Berkshire Hills on the Boston and Albany. This influenced a great deal about the line, from advertising to locomotive design, built around its flagship New York-Chicago Water Level Route.[14]

Bypasses

A number of bypasses and cutoffs were built around congested areas.

The Junction Railroad's Buffalo Belt Line opened in 1871, providing a bypass of Buffalo to the northeast as well as a loop route for passenger trains via downtown. The West Shore Railroad, acquired in 1885, provided a bypass around Rochester. The Terminal Railway's Gardenville Cutoff, allowing through traffic to bypass Buffalo to the southeast, opened in 1898.

The Schenectady Detour consisted of two connections to the West Shore Railroad, allowing through trains to bypass downtown Schenectady. The full project opened in 1902. The Cleveland Short Line Railway built a bypass of Cleveland, Ohio, completed in 1912. In 1924, the Alfred H. Smith Memorial Bridge was constructed as part of the Hudson River Connecting Railroad's Castleton Cut-Off, a 27.5-mile-long freight bypass of the congested West Albany terminal area and West Albany Hill.

An unrelated realignment was made in the 1910s at Rome, when the Erie Canal was realigned and widened onto a new alignment south of downtown Rome. The NYC main line was shifted south out of downtown to the south bank of the new canal. A bridge was built southeast of downtown, roughly where the old main line crossed the path of the canal, to keep access to and from the southeast. West of downtown, the old main line was abandoned, but a brand-new railroad line was built, running north from the NYC main line to the NYC's former Rome, Watertown and Ogdensburg Railroad, allowing all NYC through traffic to bypass Rome.

Trains

Steam locomotives of the New York Central Railroad were optimized for speed on that flat raceway of a main line, rather than slow mountain lugging. Famous locomotives of the system included the well-known 4-6-4 Hudsons, particularly the 1937–38 J-3a's; 4-8-2 World War II–era 1940 L-3 and 1942 L-4 Mohawks; and the 1945–46 S-class Niagaras: fast 4-8-4 locomotives often considered the epitome of their breed by steam locomotive aficionados (railfans).

For the first two-thirds of the 20th century, New York Central Railroad had some of the most famous trains in the United States. The 20th Century Limited (Century), begun in 1902, ran between Grand Central Terminal in New York City and LaSalle Street Station in Chicago, and was its most famous train, known for its red-carpet treatment and first-class service. Its last run was made on December 2–3, 1967.

In the mid-1930s, many railroad companies were introducing streamlined locomotives; until the New York Central introduced the Commodore Vanderbilt, all were diesel-electric. The Vanderbilt was the NYC's first streamlined steam locomotive.[15]

The railroad hosted the streamlined steam-powered Rexall Train of 1936, which toured 47 states to promote the Rexall chain of drug stores and to provide space for company conventions.[16] The steam-powered Century, which followed the Water Level Route, could complete the 960.7-mile trip in 16 hours after its June 15, 1938 streamlining (and did it in 151⁄2 hours for a short period after World War II). Also famous were the NYC's Empire State Express, which traveled from New York City through upstate New York to Buffalo and Cleveland, and the Ohio State Limited, which ran between New York City and Cincinnati.

At various times, beginning in 1946 and continuing into the mid-1950s, the Century and other NYC trains exchanged sleeping cars in Chicago with western trains such as the Super Chief and the City of San Francisco. The cars, which contained roomettes, double bedrooms and drawing rooms, provided through sleeper service between New York City and Los Angeles or San Francisco (Oakland Pier).[17][18]

Despite having some of the most modern steam locomotives anywhere, NYC's difficult financial position caused it to convert to more-economical diesel-electric power rapidly. The Boston and Albany line was completely dieselized by 1951.[19] All lines east of Cleveland, Ohio were dieselized between August 7, 1953 (east of Buffalo) and September 1953 (Cleveland-Buffalo). Niagaras were all retired by July 1956. On May 3, 1957, H7e class 2-8-2 Mikado type steam locomotive No. 1977 is reported to have been the last steam locomotive to retire from service on the railroad.[20] But, the economics of northeastern railroading became so dire that not even this switch could change things for the better.

Prominent New York Central trains:

New York to Chicago

- 20th Century Limited: New York to Chicago (limited stops) via the Water Level Route 1902–1967

- Commodore Vanderbilt: New York–Chicago (a few more stops) via the Water Level Route

- Lake Shore Limited: New York–Chicago via Cleveland with branch service to Boston and St. Louis 1896–1956, 1971–present (Reinstated and combined with New England States by Amtrak in 1971)

- Chicagoan: New York–Chicago

- Pacemaker: New York–Chicago all-coach train via Cleveland

- Wolverine: New York-Chicago via southern Ontario and Detroit

The Mercuries

- Chicago Mercury: Chicago-Detroit

- Cincinnati Mercury: Cleveland-Cincinnati

- Cleveland Mercury: Detroit–Cleveland

- Detroit Mercury: Cleveland-Detroit

New York to St. Louis

- Knickerbocker: New York–St. Louis

- Southwestern Limited: New York–St. Louis, from 1889 to 1966

Other trains

- Empire State Express: New York–Buffalo and Cleveland via the Empire Corridor 1891–present (as far as Niagara Falls, New York as Empire Service).

- Cleveland Limited: New York–Cleveland

- Detroiter: New York–Detroit

- Great Lakes Aerotrain: Chicago-Detroit/Cleveland 1956 (Special experimental lightweight train)

- James Whitcomb Riley: Chicago-Cincinnati

- Michigan: Chicago-Detroit

- Motor City Special: Chicago–Detroit

- New England States: Boston-Chicago via the Water Level Route 1938–1971 (Retained by Penn Central and, for Amtrak, combined with reinstated Lake Shore Limited)

- North Star: New York-Cleveland, branches to Toronto and Lake Placid

- Ohio State Limited: New York-Cincinnati via Empire Corridor

- Ohio Xplorer: Cleveland-Cincinnati 1956–1957 (Special experimental lightweight train)

- Twilight Limited: Chicago–Detroit

Trains left from Grand Central Terminal in New York, Weehawken Terminal in Weehawken, New Jersey, South Station in Boston, Cincinnati Union Terminal in Cincinnati, Michigan Central Station in Detroit, St. Louis Union Station, and LaSalle Street Station and Central Station (for some Detroit and CincinnatI trains) in Chicago.

The New York Central had a network of commuter lines in New York and Massachusetts. Westchester County, New York had the railroad's Hudson, Harlem, and Putnam lines into Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan (Putnam Division trains required a change at High Bridge, New York), while New Jersey and Rockland County, New York were serviced by the West Shore Line between Weehawken and Kingston, New York, on the west side of the Hudson River.

Decline

The New York Central, like many U.S. railroads, declined after the Second World War. Problems resurfaced that had plagued the railroad industry before the war, such as over-regulation by the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), which severely regulated the rates charged by the railroad, along with continuing competition from automobiles and trucks. These problems were coupled with even more-formidable forms of competition, such as airline service in the 1950s that began to deprive NYC of its long-distance passenger trade. The Interstate Highway Act of 1956 helped create a network of government subsidized highways for motor vehicle travel throughout the country, enticing more people to travel by car, as well as haul freight by truck. The 1959 opening of the Saint Lawrence Seaway also adversely affected NYC freight business: container shipments could now be directly shipped to ports along the Great Lakes, eliminating the railroads' freight hauls between the east and the Midwest.

The NYC also carried a substantial tax burden from governments that saw rail infrastructure as a source of property tax revenues – taxes that were not imposed upon interstate highways. To make matters worse, most railroads, including the NYC, were saddled with a World War II-era tax of 15% on passenger fares, which remained until 1962: 17 years after the end of the war.[21]

Robert R. Young: 1954–1958

In June 1954, management of the New York Central System lost a proxy fight in 1954 to Robert Ralph Young and the Alleghany Corporation he led.[22]

Alleghany Corporation was a real estate and railroad empire, built by the Van Sweringen brothers of Cleveland in the 1920s, that had controlled the Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) and the Nickel Plate Road. It fell under the control of Young and financier Allan Price Kirby during the Great Depression.

Young was considered a railroad visionary but found the NYC in worse shape than he had imagined. Unable to keep his promises, Young was forced to suspend dividend payments in January 1958. He committed suicide later that month at his mansion in Palm Beach, Florida.[23]

Alfred E. Perlman: 1958–1968

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 35,929 |

| 1933 | 20,692 |

| 1944 | 51,922 |

| 1960 | 32,329 |

| 1967 | 38,901 |

| Year | Traffic |

|---|---|

| 1925 | 4,261 |

| 1933 | 2,238 |

| 1944 | 9,292 |

| 1960 | 1,797 |

| 1967 | 939 |

After Young's suicide, his role in NYC management was assumed by Alfred E. Perlman, who had been working with the NYC under Young since 1954. Despite the dismal financial condition of the railroad, Perlman was able to streamline operations and save the company money. In 1959, Perlman was able to reduce operating deficits by $7.7 million, which nominally raised NYC stock to $1.29 per share, producing dividends of an amount not seen since the end of the war. By 1964 he was able to reduce the NYC long-term debt by nearly $100 million, while reducing passenger deficits from $42 to $24.6 million.

Perlman also enacted several modernization projects throughout the railroad. Notable was the use of Centralized Traffic Control (CTC) systems on many of the NYC lines, which reduced the four-track mainline to two tracks. He oversaw construction and/or modernization of many hump or classification yards, notably the $20 million Selkirk Yard, which opened south of Albany in 1924 and was modernized in 1966. Perlman also experimented with jet trains, creating a Budd RDC car (the M-497 Black Beetle) powered by two J47 jet engines stripped from a B-36 Peacemaker bomber as a solution to increasing car and airplane competition. This project did not leave the prototype stage.

Perlman's cuts resulted in the curtailing of many of the railroad's services; commuter lines around New York were particularly affected. In 1958–1959, service was suspended on the NYC's Putnam Division in Westchester and Putnam counties, and the NYC abandoned its ferry service across the Hudson to Weehawken Terminal. This negatively impacted the railroad's West Shore Line, which ran along the west bank of the Hudson River from Jersey City to Albany, which saw long-distance service to Albany discontinued in 1958 and commuter service between Jersey City and West Haverstraw, New York terminated in 1959. Ridding itself of most of its commuter service proved impossible due to the heavy use of these lines around metro New York, where governments mandated that the railroad still operate.

Many long-distance and regional passenger trains were either discontinued or downgraded in service, with coaches replacing Pullman, parlor, and sleeping cars on routes in Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio. The Empire Corridor between Albany and Buffalo saw service greatly reduced, with service beyond Buffalo to Niagara Falls discontinued in 1961. On December 3, 1967, most of the great long-distance trains ended, including the famed Twentieth Century Limited. The railroad's branch-line service off the Empire Corridor in upstate New York was also gradually discontinued, the last being its Adirondack Division line between Utica and Lake Placid, on April 24, 1965. Many of the railroad's great train stations in Rochester, Schenectady, and Albany were demolished or abandoned. Despite the savings these cuts created, it was apparent that, if the railroad was to become solvent again, a more permanent solution was needed.

Demise

Merger with the Pennsylvania Railroad

One problem that many of the Northeastern railroads faced was the fact that the railroad market was saturated for the dwindling rail traffic that remained. The NYC had to compete with its two biggest rivals: the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O), in addition to more moderate-size railroads such as the Delaware, Lackawanna, and Western Railroad (DLW), the Erie Railroad, the Reading Company, the Central Railroad of New Jersey and the Lehigh Valley Railroad.

Mergers of these railroads seemed a promising way for these companies to streamline operations and reduce the competition. The DL&W and Erie railroads had showed some success when they began merging their operations in 1958, finally leading to the formation of the Erie Lackawanna Railroad in 1960.

Other mergers combined the Virginian Railway, Wabash Railroad, Nickel Plate Road and several others into the Norfolk and Western Railway (N&W) system, and the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad (B&O), Western Maryland Railway (WM) and Chesapeake and Ohio Railway (C&O) combined with others to form the Chessie System. Heavy streamlining and reduction in passenger services led to the success of many of these mergers.

Following this trend, the NYC began to look for a potential railroad to merge with as early as the mid-1950s and had originally sought-out mergers with the B&O, Milwaukee Road and the NYC-controlled Nickel Plate Road. Unlike the aforementioned mergers, however, a NYC merger proved tricky due to the fact that it still operated a fairly-extensive amount of regional and commuter passenger services that was under mandates by the Interstate Commerce Commission to maintain.

It soon became apparent that the only other railroad with enough capital to allow for a potentially-successful merger was the NYC's chief rival, the PRR: itself a railroad that still had a large passenger trade. Merger talks between the two roads were discussed as early as 1955; however, this was delayed due to a number of factors: among them, interference by the Interstate Commerce Commission, objections from operating unions, concerns from competing railroads and the inability of the two companies themselves to formulate a merger plan, thus delaying progress for over a decade.

Two major points of contention centered on which railroad should have the majority controlling-interest going into the merger. Perlman's cost-cutting during the '50s and '60s put NYC in a more financially-healthy situation than the PRR. Nevertheless, the ICC, with urging by PRR President Stuart T. Saunders, wanted the PRR to absorb the NYC. Another point centered on the ICC's wanting to force the bankrupt New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad, better known as the New Haven, into the new system, which it did in 1969: something to which both companies strongly objected (with excellent financial cause). Eventually, both points would ultimately lead to the new Penn Central's demise.

On January 26, 1968, the NYC's last passenger timetable became effective. The final timetable revealed a drastically truncated schedule in anticipation of its merger with the PRR. Most local and long-distance passenger service had ended on December 3, 1967, including that of the 20th Century Limited.[24]

Penn Central: 1968–1976

On February 1, 1968, the New York Central was absorbed by the Pennsylvania Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad was renamed Pennsylvania New York Central Transportation Company and then eventually renamed to the Penn Central Transportation Company (PC), with NYC's Perlman elected as PC's president.[25] PC was quickly saddled with debt when the ICC forced the money-losing New Haven into the railroad in 1969.[23] Additionally, there was a conflict between Perlman and PC's CEO Stuart T. Saunders, where the former requested $25 million to refurbish PC's freight car roster and the latter declined, thus leading to Perlman's resignation.[26][27]

The two companies' competing corporate cultures, union interests and incompatible operating and computer systems sabotaged any hope for a success. Additionally, in an effort to look profitable, the board of directors authorized the use of the railroad's reserve cash to pay dividends to company stockholders. Nevertheless, on June 1, 1970, Penn Central declared bankruptcy: the largest private bankruptcy in the United States up to that time.[27] Under bankruptcy protection, many of Penn Central's outstanding debts owed to other railroads were frozen, while debts owed to Penn Central by the other roads were not. This sent a trickle effect throughout the already-fragile railroad industry, forcing many of the other Northeastern railroads into insolvency: among them the Erie Lackawanna, Boston and Maine, Central Railroad of New Jersey, the Reading Company and the Lehigh Valley.[27]

Penn Central marked the last hope of privately funded passenger rail service in the United States. In response to the bankruptcy, President Richard Nixon signed into law the Rail Passenger Service Act of 1970 which formed the National Railroad Passenger Corporation, better known as Amtrak: a government-subsidized railroad system. On May 1, 1971, Amtrak took over the operation of most regional and long-distance intercity passenger trains in the United States.[28] Amtrak would eventually assume ownership of the Northeast Corridor, a mostly-electrified route between Boston and Washington, D.C., inherited primarily from the PRR and New Haven systems. Penn Central and the other railroads were still obligated to operate their commuter services for the next five years while in bankruptcy, eventually turning them over to the newly formed Conrail in 1976. There was some hope that Penn Central, and the other Northeastern railroads, could be restructured toward profitability once their burdensome passenger deficits were unloaded. However, this was not to be, and the railroads never recovered from their respective bankruptcies.

Conrail and CSX: 1976–present

Conrail, officially the Consolidated Rail Corporation, created by the U.S. government to salvage Penn Central and the other bankrupt railroads' freight business, beginning its operations on April 1, 1976.[27] As mentioned, Conrail assumed control of Penn Central's commuter lines throughout the Lower Hudson Valley of New York, Connecticut, and in and around Boston. In 1983, these commuter services would be turned over to the state-funded Metro-North Railroad in New York and Connecticut, and Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority in Massachusetts. Conrail would go on to achieve profitability by the 1990s and was sought by several other large railroads in a continuing trend of mergers, eventually having its assets absorbed by CSX and Norfolk Southern in 1999.

Conrail, in an effort to streamline its operations, was forced to abandon miles of both NYC and PRR trackage. Nevertheless, the majority of the NYC system is still intact and used by both CSX and Amtrak. Among the lines still used are the famed Water Level Route between New York and Chicago, as well as the former Boston & Albany line between these points, the Kankakee Belt Route through Indiana, Illinois and Iowa, and the West Shore Line between Jersey City and the Albany suburb of Selkirk, where the old NYC (now CSX) Selkirk Yard is among the busiest freight yards in the country.

On June 6, 1998, most of Conrail was split between Norfolk Southern and CSX. New York Central Lines LLC was formed as a subsidiary of Conrail, containing the lines to be operated by CSX: this included the old Water Level Route as far as Cleveland, Ohio (the Cleveland–Chicago portion going to Norfolk Southern since the ex-PRR Fort Wayne line had been downgraded under Conrail), the Big Four route between Cleveland and St. Louis, and many other lines of the New York Central, as well as various lines from other companies, and also assumed the NYC reporting mark. CSX eventually fully absorbed the subsidiary as part of a streamlining of Conrail operations.

Officers of the New York Central Railroad

Presidents

- Erastus Corning (1853–1865)

- Cornelius Vanderbilt (1867 – ?)

- James H. Rutter (1883–1885)

- Chauncey M. Depew (1885–1898)

- Samuel R. Callaway (1898–1901)

- William C. Brown (? – 1914)

- Alfred H. Smith (1914–1918, 1919–1924)

- Patrick E. Crowley (1924–1931)

- Frederic E. Williamson (1931–1944)

- Gustav Metzman (1944–1952)

- William White (1952–1954)

- Robert R. Young (1954–1958)

- Alfred E. Perlman (1958–1968)

See also

- National New York Central Railroad Museum, in Elkhart, Indiana

- George Henry Daniels, associated publicist

- New York Central Tugboat 13, used to push rail barges

- Four-Track News, company publication

Notes

- ^ Totals include B&A, MC, CCC&StL, Cinc Northern and EI&TH, but not P&LE, Fulton Chain, Raquette Lake, Federal Valley, Kankakee & Seneca or Chicago Kalamazoo & Saginaw

- ^ a b Totals include subsidiary roads like B&A, MC, Big Four, EI&TH, K&M etc but not P&LE, Kankakee & Seneca, Fulton Chain, Raquette Lake or Federal Valley

References

- ^ "Michigan's Railroad History 1825 - 2014" (PDF). Michigan Department of Transportation. October 13, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2024.

- ^ "About N.Y.C." NYCSHS – New York Central System Historical Society. June 18, 2013. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Klein (1985), p. 16.

- ^ Solomon & Schafer (1999), p. 13.

- ^ Klein (1985), p. 12.

- ^ Munsell, J. Mohawk and Hudson Rail Road

- ^ a b Solomon & Schafer (1999), p. 14.

- ^ Lawrence, Scot. "A History of Rochester New York Railroads". gold.mylargescale.com. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ Starr, Timothy. (2022). The Back Shop Illustrated, Volume 1.

- ^ "Why President Newman Quit – The Railroad Age Gazette Blames the "Incompetent" Board of Directors". The New York Times. January 3, 1909. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Central Road's New Head – William H. Newman of the Lake Shore Elected President – Mr. Van Etten Becomes Second Vice President -- P.S. Blodgett Succeeds Him as General Superintendent". The New York Times. June 4, 1901. Retrieved November 29, 2021.

- ^ "Michigan's Railroad History 1825–2014" (PDF). Michigan Department of Transportation. October 13, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ Starr, Timothy. (2022). The Back Shop Illustrated, Volume 1.

- ^ "The New York Central System". american-rails.com. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2018.

- ^ "Streamline Steam Engine Attains High Speed". Popular Mechanics. Hearst Magazines. February 1935. p. 211 – via Google Books.

- ^ (1) "The Rexall Train". American-Rails.com. Archived from the original on February 20, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

(2) "The 1936 Million Dollar Rexall Streamlined Train". The Story of the Rexall Train of 1936. themetrains.com. Archived from the original on March 5, 2021. Retrieved April 23, 2021. - ^ "The Super Chief – "The Train of the Stars"". New York Social Diary. December 6, 2020. Archived from the original on December 6, 2020. Retrieved June 1, 2024 – via web.archive.org.

- ^ "M-10004 City of San Francisco". www.thecoachyard.com. Retrieved June 1, 2024.

- ^ Solomon & Schafer (1999), p. 65.

- ^ Drury (2015), p. 234.

- ^ "Brief History of the U.S. Passenger Rail Industry". Archived from the original on October 23, 2007.

- ^ "Railroads: Young Takes Over". Time. Retrieved May 6, 2018.[dead link]

- ^ a b Klein (1985), pp. 105–109.

- ^ "New York Central System: Passenger Timetable" (PDF). New York Central Railroad. January 26, 1968. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 4, 2019. Retrieved April 22, 2021 – via canadasouthern.com.

- ^ Lennon, J. Establishing Trails on Rights-of-Way. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of the Interior. p. 51.

- ^ Klein (1985), p. 111.

- ^ a b c d Solomon & Schafer (1999), p. 125.

- ^ Klein (1985), p. 115.

Bibliography

- Drury, George H. (2015). Guide to North American Steam Locomotives (2nd ed.). Kalmbach Media. ISBN 978-1-62700-259-2.

- Klein, Aaron E. (1985). The History of the New York Central System (1st ed.). Bonanza Books. ISBN 0-517-46085-8.

- Solomon, Brian; Schafer, Mike (1999). New York Central Railroad. Railroad Color History (1st ed.). MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 0-7603-0613-3.

External links

- New York Central System Historical Society

- National New York Central Railroad Museum Archived September 5, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "Public Timetables of the New York Central". Archived from the original on March 3, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021 – via canadasouthern.com.

- The Steam Locomotive (1938 documentary)

- Works by or about New York Central Railroad at the Internet Archive