Understanding Media

Cover of first edition | |

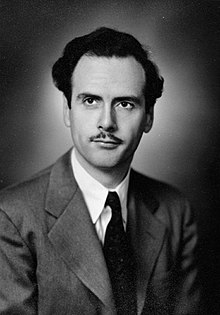

| Author | Marshall McLuhan |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Media theory |

| Publisher | McGraw-Hill |

Publication date | 1964 |

| Publication place | Canada |

| Media type | Print (hardcover and paperback) |

| Pages | 318 (first edition) |

| ISBN | 81-14-67535-7 |

Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man is a 1964 book by Marshall McLuhan, in which the author proposes that the media, not the content that they carry, should be the focus of study. He suggests that the medium affects the society in which it plays a role mainly by the characteristics of the medium rather than the content. The book is considered a pioneering study in media theory.

McLuhan pointed to the light bulb as an example. A light bulb does not have content in the way that a newspaper has articles or a television has programs, yet it is a medium that has a social effect; that is, a light bulb enables people to create spaces during nighttime that would otherwise be enveloped by darkness. He describes the light bulb as a medium without any content. McLuhan states that "a light bulb creates an environment by its mere presence".[1]

More controversially, he postulated that content had little effect on society—in other words, it did not matter if television broadcasts children's shows or violent programming. He noted that all media have characteristics that engage the viewer in different ways; for instance, a passage in a book could be reread at will, but a movie had to be screened again in its entirety to study any individual part of it.

The book is the source of the well-known phrase "the medium is the message". It was a leading indicator of the upheaval of local cultures by increasingly globalized values. The book greatly influenced academics, writers, and social theorists. The book discussed the radical analysis of social change, how society is shaped, and reflected by communications media.

Summary

Throughout Understanding Media, McLuhan uses historical quotes and anecdotes to probe the ways in which new forms of media change the perceptions of societies, with specific focus on the effects of each medium as opposed to the content that is transmitted by each medium. McLuhan identified two types of media: "hot" media and "cool" media, drawing from French anthropologist Lévi-Strauss' distinction between hot and cold societies.[2][3]

This terminology does not refer to the temperature or emotional intensity, nor some kind of classification, but to the degree of participation. Cool media are those that require high participation from users, due to their low definition (the receiver/user must fill in missing information). Since many senses may be used, they foster involvement. Conversely, hot media are low in audience participation due to their high resolution or definition. Film, for example, is defined as a hot medium, since in the context of a dark movie theater, the viewer is completely captivated, and one primary sense—visual—is filled in high definition. In contrast, television is a cool medium, since many other things may be going on and the viewer has to integrate all of the sounds and sights in the context.

In Part One, McLuhan discusses the differences between hot and cool media and the ways that one medium translates the content of another medium. Briefly, "the content of a medium is always another medium".

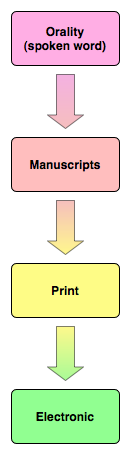

In Part Two, McLuhan analyzes each medium (circa 1964) in a manner that exposes the form, rather than the content of each medium. In order, McLuhan covers:

- The Spoken Word;

- The Written Word (i.e., manuscript or incunabulum);

- Roads and Paper Routes;

- Numbers;

- Clothing;

- Housing;

- Money;

- Clocks;

- The Print (i.e., pictorial lithograph or woodcut);

- Comics;

- The Printed Word (i.e., typography);

- The Wheel;

- The Bicycle and Airplane;

- The Photograph;

- The Press;

- The Motorcar;

- Ads;

- Games;

- The Telegraph;

- The Typewriter;

- The Telephone;

- The Phonograph;

- Movies;

- Radio;

- Television;

- Weapons; and

- Automation.

Concept of "media"

McLuhan uses interchangeably the words medium, media, and technology.

For McLuhan a medium is "any extension of ourselves" or, more broadly, "any new technology".[4] Contrastly, in addition to forms such as newspapers, television, and radio, McLuhan includes the light bulb,[5] cars, speech, and language in his definition of media: all of these, as technologies, mediate our communication; their forms or structures affect how we perceive and understand the world around us.

McLuhan says that conventional pronouncements fail in studying media because they focus on content, which blinds them to the psychic and social effects that define the medium's true significance. McLuhan observes that any medium "amplifies or accelerates existing processes", introducing a "change of scale or pace or shape or pattern into human association, affairs, and action", which results in "psychic, and social consequences".[4][5] This is the real "meaning or message" brought by a medium, a social and psychic message, and it depends solely on the medium itself, regardless of the 'content' emitted by it.[4] This is basically the meaning of "the medium is the message".

To demonstrate the flaws of the common belief that the message resides in how the medium is used (the content), McLuhan provides the example of mechanization, pointing out that regardless of the product (e.g., corn flakes or Cadillacs), the impact on workers and society is the same.[4]

In a further exemplification of the common unawareness of the real meaning of media, McLuhan says that people "describe the scratch but not the itch".[6] As an example of "media experts" who follow this fundamentally flawed approach, McLuhan quotes a statement from "General" David Sarnoff (head of RCA), calling it the "voice of the current somnambulism".[7] Each medium "adds itself on to what we already are", realizing "amputations and extensions" to our senses and bodies, shaping them in a new technical form. As appealing as this remaking of ourselves may seem, it really puts us in a "narcissistic hypnosis" that prevents us from seeing the real nature of the media.[7] McLuhan also says that a characteristic of every medium is that its content is always another (previous) medium.[5] For an example in the new millennium, the Internet is a medium whose content is various media which came before it—the printing press, radio and the moving image.

An overlooked, constantly repeated understanding McLuhan has is that moral judgement (for better or worse) of an individual using media is very difficult, because of the psychic effects media have on society and their users. Moreover, media and technology, for McLuhan, are not necessarily inherently "good" or "bad" but bring about great change in a society's way of life. Awareness of the changes are what McLuhan seemed to consider most important, so that, in his estimation, the only sure disaster would be a society not perceiving a technology's effects on their world, especially the chasms and tensions between generations.

The only possible way to discern the real "principles and lines of force" of a medium (or structure) is to stand aside from it and be detached from it. This is necessary to avoid the powerful ability of any medium to put the unwary into a "subliminal state of Narcissus trance", imposing "its own assumptions, bias, and values" on him. Instead, while in a detached position, one can predict and control the effects of the medium. This is difficult because "the spell can occur immediately upon contact, as in the first bars of a melody".[8] One historical example of such detachment is Alexis de Tocqueville and the medium of typography. He was in such position because he was highly literate.[8] Instead, an historical example of the embrace of technological assumptions happened with the Western world, which, heavily influenced by literacy, took its principles of "uniform and continuous and sequential" for the actual meaning of "rational".[8]

McLuhan argues that media are languages, with their own structures and systems of grammar, and that they can be studied as such. He believed that media have effects in that they continually shape and re-shape the ways in which individuals, societies, and cultures perceive and understand the world. In his view, the purpose of media studies is to make visible what is invisible: the effects of media technologies themselves, rather than simply the messages they convey. Media studies therefore, ideally, seeks to identify patterns within a medium and in its interactions with other media. Based on his studies in New Criticism, McLuhan argued that technologies are to words as the surrounding culture is to a poem: the former derive their meaning from the context formed by the latter. Like Harold Innis, McLuhan looked to the broader culture and society within which a medium conveys its messages to identify patterns of the medium's effects.[9]

"Hot" and "cool" media

In the first part of Understanding Media, McLuhan also states that different media invite different degrees of participation on the part of a person who chooses to consume a medium. Some media, such as film, were "hot" - that is, they enhance one single sense, in this case vision, in such a manner that a person does not need to exert much effort in filling in the details of a movie image. McLuhan contrasted this with "cool" TV, which he claimed requires more effort on the part of viewer to determine meaning, and comics, which due to their minimal presentation of visual detail require a high degree of effort to fill in details that the cartoonist may have intended to portray. A movie is thus said by McLuhan to be "hot", intensifying one single sense "high definition", demanding a viewer's attention, and a comic book to be "cool" and "low definition", requiring much more conscious participation by the reader to extract value.[10]

"Any hot medium allows of less participation than a cool one, as a lecture makes for less participation than a seminar, and a book for less than a dialogue."[11]

Hot media usually, but not always, provide complete involvement without considerable stimulus. For example, print occupies visual space, uses visual senses, but can immerse its reader. Hot media favour analytical precision, quantitative analysis and sequential ordering, as they are usually sequential, linear and logical. They emphasize one sense (for example, of sight or sound) over the others. For this reason, hot media also include radio, as well as film, the lecture and photography.

Cool media, on the other hand, are usually, but not always, those that provide little involvement with substantial stimulus. They require more active participation on the part of the user, including the perception of abstract patterning and simultaneous comprehension of all parts. Therefore, according to McLuhan cool media include television, as well as the seminar and cartoons. McLuhan describes the term "cool media" as emerging from jazz and popular music and, in this context, is used to mean "detached".[12]

Examples of media and their messages

| Explanations | Essence (the real message) | Content/use (the irrelevant message) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mechanization[4][13] | Provides human operators with machinery to assist them with the physical requirements of work. It is achieved "by fragmentation of any process and by putting the fragmented parts in a series". | The essence is the "technique of fragmentation". It is "fragmentary, centralist, and superficial" in its reshaping of human relationships. The decomposition makes a process into a sequence, which has no principle of causality. | the manufactured product (e.g. cornflakes or Cadillacs) |

| automation[4] | Uses machinery to replace human operators. | It is "integral and decentralist in depth" | the manufactured product (e.g.. cornflakes or Cadillacs) |

| movie[13] | Speeds up the mechanical (a sequence of frames) | With the "sheer speeding up the mechanical, it carried us from the world of sequence and connections into the world of creative configuration and structure. The message of the movie medium is that of transition from lineal connections to configuration." | |

| electricity[13][14] | The electric age | The instant speed of electricity brought simultaneity. It ended the sequencing/concatenation introduced by mechanization, and so "the causes of things began to emerge to awareness again". "The electric speed further takes over from mechanical movie sequences, then the lines of force in structures and in media become loud and clear. We return to the inclusive form of the icon." It imposed the shift from the approach of focusing on "specialized segments of attention" (adopting one particular perspective), to the idea of "instant sensory awareness of the whole", an attention to the "total field", a "sense of the whole pattern". It made evident and prevalent the sense of "form and function as a unity", an "integral idea of structure and configuration". This had major impact in the disciplines of painting (with cubism), physics, poetry, communication and educational theory. | |

| electric light[5] | - | "totally radical, pervasive, and decentralized... it eliminates time and space factors in human association exactly as do radio, telegraph, telephone, and TV, creating involvement in depth." | usually none. (although it can be used to "spell out some brand name") |

| electric power in industry[5] | - | the same as the electric light | (different from the electric light) |

| telegraph[5] | |||

| print and typography[5][8][15] | the new visual print culture | The message are the principles of uniformity, continuity, and linearity. Impact on human associations: the printed word, through "cultural saturation" in the 18th century, "homogenized the French nation, overlaying the complexities of ancient feudal and oral society";[16] this opened the way for the Revolution, which "was carried out by the new literati and lawyers". Limits on impact: it could not "take complete hold" on a society such as Great Britain, in which the preceding "ancient oral traditions of common law", that made the country culture so discontinuous and unpredictable and dynamic, was very powerful and "backed by the medieval legal institution of Parliament"; print culture, led instead to major revolutions in France and North America, because they were more linear and lacked contrasting institutions of comparable power. | the written word |

| writing[5] | speech | ||

| speech[5] | "It is an actual process of thought, which is in itself nonverbal" | ||

| radio[5] | |||

| telephone[5] | |||

| TV[5] | "It speaks, and yet says nothing."[17] | ||

| railway[5] | "it accelerated and enlarged the scale of previous human functions, creating totally new kinds of cities and new kinds of work and leisure." | freight; "functioning in a tropical or a northern environment" | |

| airplane[5] | "by accelerating the rate of transportation, it tends to dissolve the railway form of city, politics, and association" | fast travel |

Critiques of Understanding Media

Some theorists have attacked McLuhan's definition and treatment of the word "medium" for being too simplistic. Umberto Eco, for instance, contends that McLuhan's medium conflates channels, codes, and messages under the overarching term of the medium, confusing the vehicle, internal code, and content of a given message in his framework.[18]

In Media Manifestos, Régis Debray also takes issue with McLuhan's envisioning of the medium. Like Eco, he too is ill at ease with this reductionist approach, summarizing its ramifications as follows:[18]

The list of objections could be and has been lengthened indefinitely: confusing technology itself with its use of the media makes of the media an abstract, undifferentiated force and produces its image in an imaginary "public" for mass consumption; the magical naivete of supposed causalities turns the media into a catch-all and contagious "mana"; apocalyptic millenarianism invents the figure of a homo mass-mediaticus without ties to historical and social context, and so on.

Furthermore, when Wired interviewed him in 1995, Debray stated that he views McLuhan "more as a poet than a historian, a master of intellectual collage rather than a systematic analyst.... McLuhan overemphasizes the technology behind cultural change at the expense of the usage that the messages and codes make of that technology."[19]

Dwight Macdonald, in turn, reproached McLuhan for his focus on television and for his "aphoristic" style of prose, which he believes left Understanding Media filled with "contradictions, non-sequiturs, facts that are distorted and facts that are not facts, exaggerations, and chronic rhetorical vagueness".[20]

Additionally, Brian Winston’s Misunderstanding Media, published in 1986, chides McLuhan for what he sees as his technologically deterministic stances.[20] Raymond Williams and James W. Carey further this point of contention, claiming:

The work of McLuhan was a particular culmination of an aesthetic theory which became, negatively, a social theory ... It is an apparently sophisticated technological determinism which has the significant effect of indicating a social and cultural determinism ... If the medium - whether print or television – is the cause, of all other causes, all that men ordinarily see as history is at once reduced to effects. (Williams 1990, 126/7)[20]

David Carr states that there has been a long line of "academics who have made a career out of deconstructing McLuhan’s effort to define the modern media ecosystem", whether it be due to what they see as McLuhan's ignorance toward socio-historical context or the style of his argument.[21]

While some critics have taken issue with McLuhan's writing style and mode of argument, McLuhan himself urged readers to think of his work as "probes" or "mosaics" offering a toolkit approach to thinking about the media. His eclectic writing style has also been praised for its postmodern sensibilities[22] and suitability for virtual space.[23]

Exploring theories

McLuhan's theories about "the medium is the message" link culture and society. A recurrent topic is the contrast between oral cultures and print culture.[8]

Each new form of media, according to the analysis of McLuhan, shapes messages differently thereby requiring new filters to be engaged in the experience of viewing and listening to those messages.

McLuhan argues that as "sequence yields to the simultaneous, one is in the world of the structure and of configuration". The main example is the passage from mechanization (processes fragmented into sequences, lineal connections) to electric speed (faster up to simultaneity, creative configuration, structure, total field).[14]

Howard Rheingold comments upon McLuhan's "the medium is the message" in relation to the convergence of technology, specifically the computer. In his book Tools for Thought Rheingold explains the notion of the universal machine - the original conception of the computer.[24] Eventually computers will no longer use information but knowledge to operate, in effect thinking. If in the future computers (the medium) are everywhere, then what becomes of McLuhan's message?

Historical examples

According to McLuhan, the French Revolution and American Revolution happened under the push of print whereas the preexistence of a strong oral culture in Britain prevented such an effect.[8]

Footnotes

- ^ Understanding Media, p. 8.

- ^ Claude Lévi-Strauss (1962) The Savage Mind, ch.8

- ^ Taunton, Matthew (2019) Red Britain: The Russian Revolution in Mid-Century Culture, p.223

- ^ a b c d e f p.7

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n pp.8-9

- ^ p.10

- ^ a b p.11

- ^ a b c d e f p.15

- ^ Old Messengers, New Media: The Legacy of Innis and McLuhan Archived 2007-10-01 at the Wayback Machine, a virtual museum exhibition at Library and Archives Canada

- ^ Understanding Media, p. 22.

- ^ Understanding Media, p. 25.

- ^ See CBC Radio Archives

- ^ a b c p.12

- ^ a b p.13

- ^ p.14

- ^ Alexis de Tocqueville (1856) The Old Regime and the Revolution

- ^ quoted from Romeo and Juliet

- ^ a b Debray, Regis. "Media Manifestos" (PDF). Columbia University Press. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Joscelyne, Andrew. "Debray on Technology". Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Mullen, Megan. "Coming to Terms with the Future He Foresaw: Marshall McLuhan's Understanding Media". Archived from the original on 5 November 2011. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Carr, David (January 6, 2011). "Marshall McLuhan: Media Savant". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ^ Paul Grossweiler, The Method is the Message: Rethinking McLuhan through Critical Theory (Montreal: Black Rose, 1998), 155-81

- ^ Paul Levinson, Digital McLuhan: A Guide to the Information Millennium (New York: Routledge, 1999), 30.

- ^ "Tools for Thought by Howard Rheingold: Table of Contents".

External links

- Official website of Marshall McLuhan (author)