List of World Heritage Sites in Pakistan

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Sites are places of importance to cultural or natural heritage as described in the UNESCO World Heritage Convention, established in 1972.[1] Cultural heritage consists of monuments (such as architectural works, monumental sculptures, or inscriptions), groups of buildings, and sites (including archaeological sites). Natural features (consisting of physical and biological formations), geological and physiographical formations (including habitats of threatened species of animals and plants), and natural sites which are important from the point of view of science, conservation or natural beauty, are defined as natural heritage.[2] Pakistan ratified the convention on 23 July 1976, making its sites eligible for inclusion on the list.[3]

There are six World Heritage Sites in Pakistan, and a further 26 on the tentative list.[3] The first three sites were listed in 1980, the Archaeological Ruins at Moenjodaro, Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Neighbouring City Remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol, and Taxila. Two sites were listed in 1981 and the most recent site added to the list was the Rohtas Fort, in 1997. All six sites are cultural.[3]

World Heritage Sites

UNESCO lists sites under ten criteria; each entry must meet at least one of the criteria. Criteria i through vi are cultural, and vii through x are natural.[4]

| Site | Image | Location | Year listed | UNESCO data | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Archaeological Ruins at Moenjodaro |

|

Sindh | 1980 | 138; ii, iii (cultural) | Mohenjo-daro was one of the largest cities of the Indus Valley Civilisation and was the first planned city in South Asia. Located on the banks of the Indus River, it flourished between 2,500 and 1,500 BCE. The city was mostly built with baked brick and followed a strict grid plan. There were public baths, a granary, and an elaborate drainage system. A Buddhist stupa was built over the ruins in the 2nd century CE. The excavations at the site have been ongoing since 1922, with about one third of the city having been explored so far.[5] |

| Taxila |

|

Punjab | 1980 | 139; iii, vi (cultural) | Taxila, which was already inhabited in the Neolithic, was an important Buddhist centre of learning between the 5th century BCE and 2nd century CE. The archaeological site comprises the remains of four settlements which reveal the urban development of the site. The city was located on one of the branches of the Silk Road and was influenced by the Achaemenid Empire and by the Greeks. The Bhir Mound is associated with the entrance of Alexander the Great into Taxila in 326 BCE. Some of the monuments include the Jaulian monastery, the Mohra Muradu stupa, the Dharmarajika Stupa, the Jandial complex, and the city of Sirkap (the remains of a stupa at the site pictured).[6] |

| Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Neighbouring City Remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 1980 | 140; iv (cultural) | The Buddhist monastery of Takht-i-Bahi (pictured) was founded in the 1st century CE and remained in use until the 7th century. Due to its location on the crest of a steep hill, it remained well preserved despite successive invasions of the region. The monastery and the remains of the nearby city of Seri Bahlol from the Kushan period are some of the most important Buddhist monuments in the Gandhara region. The monastery is the most complete Buddhist monastery in Pakistan and comprises several groups of stupas, monastic cells, temples, and secular buildings.[7] |

| Historical Monuments at Makli, Thatta |

|

Sindh | 1981 | 143; iii (cultural) | Makli is a large necropolis in the city of Thatta. It was active between the 14th and 18th centuries. The monuments and mausoleums are built from high quality stone, brick, and glazed tiles. Tombs of famous saints and rulers including Jam Nizamuddin II and Isa Khan (pictured) are still preserved and are fine examples of Mughal architecture influenced by local styles.[8] |

| Fort and Shalimar Gardens in Lahore |

|

Punjab | 1981 | 171; i, ii, iii (cultural) | The Fort (pictured) and the Shalimar Gardens in Lahore are two royal complexes from the Mughal era. The Fort is located at the northwest corner of the Walled City of Lahore and has been destroyed and rebuilt several times during its history. The extant monuments date from the 16th century, during the reign of Akbar. The Shalimar Gardens were constructed under the emperor Shah Jahan in 1642. They are an example of Mughal gardens which were influenced by Persian and Islamic traditions.[9] |

| Rohtas Fort |

|

Punjab | 1997 | 586; ii, iv (cultural) | The fort was constructed under Sher Shah Suri, following his victory over the Mughal Emperor Humayun in 1541. It is an exceptional example of early Islamic military architecture in the gunpowder era, integrating artistic traditions from Turkey and the Indian subcontinent. It served as a model for the later Mughal architecture. It was never conquered in battle and remains intact today.[10] |

Tentative list

In addition to sites inscribed on the World Heritage List, member states can maintain a list of tentative sites that they may consider for nomination. Nominations for the World Heritage List are only accepted if the site was previously listed on the tentative list.[11] Pakistan has 26 properties on its tentative list.[3]

| Site | Image | Location | Year listed | UNESCO criteria | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Badshahi Mosque, Lahore |

|

Punjab | 1993 | (cultural) | This mosque in the city of Lahore is an exceptional example of Mughal architecture. It was built in 1673–74. It has four large and four smaller minarets and three marble domes. The mosque is built of red sandstone and decorated with stone reliefs and marble inlays.[12] |

| Wazir Khan Mosque, Lahore |

|

Punjab | 1993 | (cultural) | This mosque in the city of Lahore is constructed of brick and sandstone. It has five domes and four minarets and is richly decorated.[13] |

| Tombs of Jahangir, Tomb of Asif Khan and Akbari Sarai, Lahore |

|

Punjab | 1993 | (cultural) | This site comprises three monuments from the Mughal period. The tomb of the Emperor Jahangir (pictured) is made of red sandstone and richly decorated with marble inlay designs. The tomb of Abu'l-Hasan Asaf Khan is a mausoleum with a high dome that was originally decorated with marble inlay and stucco. The Akbari Sarai, a caravanserai, is located between the two monuments. The complex has 180 cells, a mosque, and two decorated gateways.[14] |

| Hiran Minar and Tank, Sheikhupura |

|

Punjab | 1993 | (cultural) | The complex in Sheikhupura was constructed in the early 17th century under the Mughal Emperor Jahangir. The large brick tower (minar) has a spiral staircase with 108 steps leading to the top. The water tank is of rectangular shape and has a causeway leading to an octagonal pavilion in the middle. The pavilion is decorated by frescoes and was used as a royal residence.[15] |

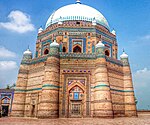

| Tomb of Shah Rukn-e-Alam |

|

Punjab | 1993, 2004 | ii, iv, vi (cultural) | The tomb was built between 1320 and 1324 inside the Multan Fort under the Tughlaq ruler Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq. It was probably intended as a dynastic tomb but instead became the tomb of the Sufi saint Shah Rukn-e-Alam. The octagonal tomb, the first of its type in South Asia, reaches 35 m (115 ft) in height. It is built in red brick and the exterior is decorated in glazed tiles and carved bricks and wood. Inside, a wooden mihrab is the earliest example of its type. The tomb is an important pilgrimage site. The site is listed twice on the UNESCO tentative list.[16][17] |

| Rani Kot Fort, Dadu |

|

Sindh | 1993 | (cultural) | The fort, located in the Dadu District, was constructed in the early 19th century. The fortification walls are 35 m (115 ft) long and follow the geography of the barren hilly area, with bastions located at intervals. There is a small fortress inside, likely used as a royal residence.[18] |

| Shah Jahan Mosque, Thatta |

|

Sindh | 1993 | (cultural) | The mosque in the city of Thatta is decorated with the most elaborate tile-work in South Asia. The mosaics with blue and white tiles cover the two main chambers and the domes. The designs include floral and geometric patterns.[19] |

| Chaukhandi Tombs, Karachi |

|

Sindh | 1993 | (cultural) | The tombs near Karachi were built for the warriors and families of the Saloch tribe in the 17th and 18th centuries. They are pyramidal in shape and covered with decorative stone carvings, depicting humans and decorative designs. Some tombs are in the Hindu style.[20] |

| Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh |

|

Balochistan | 2004 | ii, iv (cultural) | The archaeological site of Mehrgar is a tell, an artificial mound created as a result of successive settlements at the same site through generations. Initially likely seasonally occupied by pastoralist groups, the site was permanently inhabited form the aceramic Neolithic period in the 7th millennium BCE to the Chalcolithic period. The site was already abandoned in the mid-3rd millennium BCE, before the urbanised phase of the Indus Valley Civilisation. Excavations uncovered mud-brick structures (pictured) believed to be used for storage, remains of a Bronze Age village with its own craft zone, and several cemeteries. It was rediscovered in the 1970s after being exposed by a flash flood.[21] |

| Archaeological Site of Rehman Dheri |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 2004 | i, ii (cultural) | Rehman Dheri is an archaeological site that dates from the Pre-Harappan period in the 4th millennium BCE to the Early-Harappan period in the mid-3rd millennium BCE. It is one of the best preserved examples of an early urban settlement in South Asia, because the site was abandoned during the mature Harappan period. The settlement has streets following a grid plan, which was replicated in the successive phases. There are remains of kilns and pottery shards.[22] |

| Archaeological Site of Harappa |

|

Punjab | 2004 | ii, iv (cultural) | Harappa is an archaeological site of the Indus Valley civilisation, which was occupied from the 4th to the 2nd millennium BCE, with its peak between 2600 and 1900 BCE. It is a tell, an artificial mound created as a result of successive settlements at the same site through generations. Harappa was located next to the old course of the Ravi River which provided the inhabitants fresh water and access to trade networks. There are eight mounds and two cemeteries on site, as well as some structures from the Gupta and Mughal Empires and a modern village.[23] |

| Archaeological Site of Ranigat |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 2004 | ii, iv (cultural) | The archaeological site of Ranigat is the largest Buddhist monastic complex in the Gandhara region, where a culture blending the Hellenistic, Buddhist, and Indo-Parthian traditions flourished between the 2nd century BCE and 6th century CE. The monastery was founded in the 1st century CE. Excavations in the 1980s uncovered the remains of several stupas, shrines, and secular buildings, as well as copper coins, pottery, and stone sculptures.[24][25] |

| Shahbazgarhi Rock Edicts |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 2004 | i, ii, iv (cultural) | The Edicts of Ashoka in Shahbazgarhi date to the middle of the 3rd Century BCE, during the reign of the Mauryan Emperor Ashoka. They were carved in two large boulders in the Kharosthi script and describe in detail Ashoka's view on dhamma, or righteous law. The edicts are the oldest irrefutable examples of writing in South Asia.[26] |

| Mansehra Rock Edicts |

|

Khyber Pakhtunkhwa | 2004 | ii, iii, vi (cultural) | The Edicts of Ashoka in Mansehra date to the middle of the 3rd Century BCE, during the reign of Mauryan Emperor Ashoka. They were carved in three large boulders in the Kharosthi script and describe in detail Ashoka's view on dhamma, or righteous law. The edicts are the oldest irrefutable examples of writing in South Asia.[27] |

| Baltit Fort |

|

Gilgit Baltistan | 2004 | i, ii (cultural) | The fort is overlooking the Hunza valley, an important trade route connecting South and Central Asia. The original structure dates from the 8th century and was later expanded, the current building has three floors. It is built in stone with additional timber frameworks to provide stabilization in an earthquake-prone area. The fort was the residence of the Mir, the rulers of the State of Hunza, until 1945.[28] |

| Tombs of Bibi Jawindi, Baha'al-Halim and Ustead and the Tomb and Mosque of Jalaluddin Bukhari |

|

Punjab | 2004 | ii, iv, vi (cultural) | This site comprises five monuments from the 14th and 15th centuries in the city of Uch. The tomb of the Sufi saint Jahaniyan Jahangasht has a square plan and a flat roof while the tombs of Bibi Jawindi (pictured), Baha'al-Halim, and Ustead are octagonal and feature a dome. They are decorated with glazed tiles. The mosque is also decorated with tiles featuring floral and geometric designs. Some of the tombs have been damaged by erosion.[29] |

| Port of Banbhore |

|

Sindh | 2004 | iv, v, vi (cultural) | The port of Banbhore was located at the mouth of the Indus River. Founded in the 1st century BCE, the main findings date from the Islamic period between the 8th and 13th centuries, including the remains of one of the earliest mosques in the region, dating to 727. The mosque incorporates some reused stones from a previous Hindu structure. The port was important in the trade of ceramics and metal goods, and it had an industrial area with workshops dealing with textiles, glass, glazes, and metallurgy. As the river changed course in the 11th century, the creek silted, leading to the gradual abandonment of the port.[30] |

| Derawar and the Desert Forts of Cholistan |

|

Punjab | 2016 | iii, v (cultural) | This site comprises ten forts in the Cholistan Desert that were built to protect the caravan, merchant, and pilgrimage routes through the region. The best preserved fort is the Derawar fort (pictured) which was built in the 9th century by Rai Jajja Bhati of the Rajput Bhati clan. In the 18th century, it was taken over by Bahawalpur and remained the residence of the Nawab until the 1970s, constant occupation contributing to its preservation. The massive fort has 40 circular bastions that reach 30 m (98 ft) high.[31] |

| Hingol Cultural Landscape |

|

Balochistan | 2016 | iii, vi (cultural) | Hinglaj Mata mandir is an ancient Hindu cave temple located in Hingol National Park. It is dedicated to Shaktior Sati. Every year, it attracts thousands of pilgrims who cross the ravine and proceed through the cave, with stops at landmarks for religious observances. Pilgrims also visit several mud volcanos in the area (Chandragup pictured).[32] |

| Karez System Cultural Landscape |

|

Balochistan | 2016 | ii, vi, v (cultural) | A karez, kariz, or qanat is a system for transporting water from an aquifer or water well to the surface, through an underground aqueduct (scheme pictured). The technology probably developed in the 1st millennium BCE in Persia and then spread to arid and semi-arid areas of China, South Asia, Middle East, North Africa, and Spain. Tapping into the subterranean water sources allowed settlement and agriculture in areas that would otherwise be unexploitable. More than 1000 such systems are still operational in Pakistan, four are listed in the nomination.[33] |

| Nagarparkar Cultural Landscape |

|

Sindh | 2016 | iii, iv (cultural) | The cultural landscape is located in Nagarparkar, on the border of the Thar Desert. It was a centre of a thriving Jain community which was active in maritime trade, as the area was located at the coast of the Arabian Sea as late as in the 15th century. Several Jain monuments remain from the period between the 12th and 15th centuries, including the Gori Temple (pictured). Due to the changes of the coastline due to silting by the Indus River system, the community declined in numbers, with the last members leaving following the partition of India in 1947.[34] |

| Central Karakoram National Park |

|

Gilgit Baltistan | 2016 | ix, x (natural) | The national park covers large part of the central Karakoram mountain range. Four peaks over 8,000 m (26,000 ft) are located in the park, as well as several glaciers (the Baltoro Glacier pictured). The area is a highly active tectonic zone, as a result of the Himalayan orogeny. The area is also an important stopover for migrating birds and home to endangered mammal species, including markhor, musk deer, snow leopard, urial, and Marco Polo sheep.[35] |

| Deosai National Park |

|

Gilgit Baltistan | 2016 | ix, x (natural) | Deosai National Park is an alpine plateau with an altitude between 3,500 to 5,200 m (11,500 to 17,100 ft). The landscape is mostly flat with rolling hills. Due to its location at the meeting of the Himalayan and Karakorum-Pamir ecoregions, the area is rich in biodiversity. Some of the species that live here include the Himalayan brown bear, Tibetan wolf, Himalayan ibex, and Golden marmot. The Sheosar Lake (pictured), at the altitude of 4,250 m (13,940 ft), represents a unique type of alpine wetland.[36] |

| Ziarat Juniper Forest |

|

Balochistan | 2016 | x (natural) | The juniper (Juniperus excelsa polycarpos) forests around the city of Ziarat are located at the meeting point of five vegetation zones. The large forest is home to trees that are believed to be thousands of years old, but the ecosystem is vulnerable in view of climate change. The area is home to the Balochistan black bear, Himalayan brown bear, markhor, numerous bird species, and several plant species with medicinal properties that are used by the local people.[37] |

| The Salt Range and Khewra Salt Mine |

|

Punjab | 2016 | v, viii (mixed) | The geological formation of Salt Range formed 800 million years ago with the evaporation of a shallow sea, resulting in thick deposits of rock salt. Due to lack of plant cover, the area provides an excellent opportunity to study geological layers from the Cambrian to the Paleogene, with several layers bearing fossils. The salt reserves at Khewra have been known at least since the 4th century BCE when Alexander the Great crossed the area, while the salt mine (pictured) has been in operation for over a thousand of years.[38] |

See also

- List of Intangible Cultural Heritage elements in Pakistan

- Cultural heritage in Pakistan

- List of parks and gardens in Pakistan

- List of forts in Pakistan

- List of museums in Pakistan

References

- ^ "The World Heritage Convention". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2019.

- ^ "Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 February 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Pakistan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ "UNESCO World Heritage Centre The Criteria for Selection". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 12 June 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2018.

- ^ "Archaeological Ruins at Moenjodaro". UNESCO World Heritage Centre World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ "Taxila". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ "Buddhist Ruins of Takht-i-Bahi and Neighbouring City Remains at Sahr-i-Bahlol". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 5 August 2022.

- ^ "Historical Monuments at Makli, Thatta". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "Fort and Shalamar Gardens in Lahore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 29 November 2005. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "Rohtas Fort". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ^ "Tentative Lists". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

- ^ "Badshahi Mosque, Lahore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 4 March 2020. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Wazir Khan's Mosque, Lahore, Lahore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2 August 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Tombs of Jahangir, Asif Khan and Akbari Sarai, Lahore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Hiran Minar and Tank, Sheikhupura". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Tomb of Shah Rukn-e-Alam". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 March 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ "Tomb of Hazrat Rukn-e-Alam, Multan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ "Rani Kot Fort, Dadu". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 25 December 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Shah Jahan Mosque, Thatta". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 3 October 2018. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Chaukhandi Tombs, Karachi". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Mehrgarh". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Rehman Dheri". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Harappa". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Archaeological Site of Ranigat". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Ranigat: 2nd to 6th Century AD". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 12 August 2022. Retrieved 9 August 2022.

- ^ "Shahbazgarhi Rock Edicts". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Mansehra Rock Edicts". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 2 September 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Baltit Fort". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 8 August 2012. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Tomb of Bibi Jawindi, Baha'al-Halim and Ustead and the Tomb and Mosque of Jalaluddin Bukhari". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 12 June 2021. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Port of Banbhore". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 31 December 2019. Retrieved 18 September 2012.

- ^ "Derawar and the Desert Forts of Cholistan". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Hingol Cultural Landscape". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Karez System Cultural Landscape". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Nagarparkar Cultural Landscape". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 7 January 2019. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Central Karakorum National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Deosai National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "Ziarat Juniper Forest". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.

- ^ "The Salt Range and Khewra Salt Mine". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Archived from the original on 26 December 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2016.