Tusculum

Tusculo (in Italian) | |

Archaeological park of Tusculum | |

| Location | Frascati, Province of Rome, Lazio, Italy |

|---|---|

| Region | Latium |

| Coordinates | 41°47′54″N 12°42′39″E / 41.79833°N 12.71083°E |

| Type | Settlement |

| History | |

| Abandoned | 1191 AD |

| Periods | Ancient Roman to High Medieval |

Tusculum is a ruined Roman city in the Alban Hills, in the Latium region of Italy.[1] Tusculum was most famous in Roman times for the many great and luxurious patrician country villas sited close to the city, yet a comfortable distance from Rome (notably the villas of Cicero and Lucullus).[2]

Location

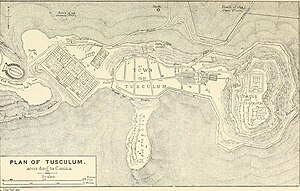

Tusculum is located on Tuscolo hill on the northern edge of the outer crater rim of the Alban volcano. The volcano itself is located in the Alban Hills 6 km (4 mi) south of the present-day town of Frascati.

The summit of the hill is 670 m (2,200 ft) above sea level and affords a view of the Roman Campagna, with Rome lying 25 km (16 mi) to the north-west. It had a strategic position controlling the route from the territory of the Aequi and the Volsci to Rome which was important in earlier times.

Later Rome was reached by the Via Latina (from which a branch road ascended to Tusculum, while the main road passed through the valley to the south of it), or by the Via Labicana to the north.[3]

Most of the ancient city and the acropolis and amphitheatre have not yet been excavated archaeologically.

History

Antiquity

According to legend, the city was founded either by Telegonus, the son of Odysseus and Circe,[3] or by the Latin king Latinus Silvius, a descendant of Aeneas, who according to Titus Livius was the founder of most of the towns and cities in Latium. The geographer Filippo Cluverio discounts these legends, asserting that the city was founded by Latins about three hundred years before the Trojan War. Funerary urns datable to the 8th–7th centuries BC demonstrate a human presence in the late phases of Latin culture in this area.

Tusculum is first mentioned in history as an independent city-state with a king, a constitution and gods of its own. When Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, the last King of Rome, was expelled from the city in 509 BC,[4] he sought military help from Lars Porsenna, king of Clusium.[5] After the war between Clusium and Rome, Porsenna made a peace with Romans, and Tarquinius failed to win back his throne. Subsequently, he sought refuge with his son-in-law Octavius Mamilius, one of the leading men of Tusculum.[6] The Mamilii claimed to be descended from Telegonus, the founder of the city. Mamilius commanded the army of the Latins against the Romans at the Battle of Lake Regillus, where he was killed in 498 BC.[7] This is the point at which Rome gained predominance among the Latin cities.

The city walls can be dated between the 5th and 4th c. BC from the type and technique of construction, as visible on the North slope of the hill.

According to some accounts Tusculum subsequently became an ally of Rome, incurring the frequent hostilities of the other Latin cities.[3] In 460 BC a Sabine named Appius Herdonius occupied the Capitol. Of the Latin cities, only Tusculum quickly sent troops, commanded by the dictator Lucius Mamilius, to help the Romans. Together with the forces of the consul Publius Valerius Poplicola they were able to quash the revolt.

In 458 BC the Aequi attacked Tusculum and captured its citadel. Because of the assistance given Rome the previous year, the Romans came to their defense, and helped regain the citadel, with soldiers under the command of Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, who defeated the Aequi at the battle of Mount Algidus.

Roman Republic and Empire

In 381 BC, after an expression of complete submission to Rome, the people of Tusculum received a franchise from Rome. Tusculum became the first "municipium cum suffragio", or self-governing city. The Tusculum citizens were therefore recorded in the "Tribus Papiria". Other accounts, however, speak of Tusculum as often allied with Rome's enemies, the last being the Samnites in 323 BC.[3]

In Sulla's civil war Tusculum supported the Marians but after Sulla's victory in 82 BC it became a colonia and parts of the city wall were rebuilt.

In 54 BC, in his Orationes Pro Cn. Plancio, Marcus Tullius Cicero said: "You are from the most ancient municipium of Tusculum, from which so many consular families are originating, among which even the gens Iuventia—all other municipia (together) do not have so many (consular families) coming from them".

Varro wrote about the laws of Tusculum in De Lingua Latina, Volume 5: "New wine shall not be taken into the town before the Vinalia are proclaimed".

The town council kept the name of senate, but the title of dictator gave place to that of aedile. Notwithstanding this, and the fact that a special college of Roman equites was formed to take charge of the cults of the gods at Tusculum, and especially of the Dioscuri, the citizens resident there were neither numerous nor men of distinction.[3]

In Roman times the city had expanded into two parts: the acropolis with the temples of the Dioscuri and Jupiter Maius, and the main city along the ridge of the hill where the main street passes through the forum to the theatre.

The villas of the neighbourhood, of which 36 owners are recorded in the Republican era[8] and 131 villa sites identified,[9] had indeed acquired greater importance than the town itself, which was not easily accessible. By the end of the Republic, and still more during the imperial period, the territory of Tusculum was a favorite place of residence for wealthy Romans.[3] Seneca wrote: "Nobody who wants to acquire a home in Tusculum or Tibur for health reasons or as a summer residence, will calculate how much yearly payments are".

In 45 BC Cicero wrote a series of books in his Roman villa in Tusculum, the Tusculanae Quaestiones. In his times there were eighteen owners of villas there. An example is the so-called villa of Lucullus, which later belonged to Flavia gens, which was built in terraces on the slope of Tusculum facing Rome: the vast terrace now houses virtually all the historical centre of Frascati.[10]

Much of the territory (including Cicero's villa), but not the town itself, which lies far too high, was supplied with water by the Aqua Crabra.[3]

The last archaeological evidence of Roman Tusculum is a bronze tablet of 406 AD commemorating Anicius Probus Consul and his sister Anicia.

Roman gentes with origins in Tusculum

- Caninia gens

- Cordia gens

- Coruncania gens

- Fonteia gens

- Fulvia gens

- Furia gens

- Geminia (gens)

- Javonelia gens

- Juventia gens

- Mamilia gens

- Manlia gens

- Porcia gens, including Marcus Porcius Cato the Elder, who was born at Tusculum in 234 BC.

- Rabiria gens

Middle Ages

From the 5th to the 10th century there are no historical mentions of Tusculum. In the 10th century it was the base of the Counts of Tusculum, an important family in the Medieval History of Rome. They were a clan system whose first mentioned member is Theophylact I (died 924). His daughter Marozia married Alberic I, Marquis of Spoleto and Camerino, and was for a while the arbiter of political and religious affairs in Rome—a position which the Counts held for a long period of time. They were pro-Byzantine and against the German Emperors. From their clan came several Popes in the period between 914 and 1049.

Gregory I of Tusculum rebuilt the fortress on the Tuscolo hill, and gave as a gift the "Criptaferrata" to Saint Nilus the Younger, where the latter built a famous abbey. Gregory also headed the rebellion of the Roman people of 1001 against the German Emperor Otto III.

After 1049 the Counts of Tusculum Papacy declined as the particular "formula" of the papacy-family became outdated. Subsequent events from 1062 confirmed the change of the Counts' politics, which became pro-Emperor in opposition to the Commune of Rome. Tusculum had in this time several notable guests: Henry III, Holy Roman Emperor, and his wife Empress Agnes in 1046, the Pope Eugene III from 1149, Louis VII of France and his wife Eleanor of Aquitaine in 1149, Frederick Barbarossa and the English Pope Adrian IV in 1155.

In 1167 the Roman communal army attacked Tusculum (Battle of Monte Porzio), but it was defeated by the Emperor-allied army, headed by Christian I, Archbishop of Mainz; in the summer of the same year, however, a plague decimated the imperial army and Frederick Barbarossa was forced to return to Germany.

Destruction and rediscovery

Medieval destruction

From 1167 the residents of Tusculum moved to the neighbours (Locus) or little villages as Monte Porzio Catone, Grottaferrata and mostly to Frascati: only a little group of defence troops remained in the old city.

When in 1183 the Roman army again attacked Tusculum, Barbarossa sent a new contingent of troops to its defence. The Commune of Rome was however able to destroy the town on 17 April 1191 with the consent of Pope Celestine III and the consent of Henry VI, Holy Roman Emperor, son of Frederick Barbarossa.

Roger of Hoveden wrote "lapis supra lapidem non remansit" (not a stone upon a stone remained), indeed the Roman Commune's army took away the stones of the walls of Tusculum as spoils of war in Rome.

After destruction the land of Tusculum city became woodland and pasture lands. The buildings destroyed in Tusculum became a big open quarry of materials for the inhabitants of the neighbouring towns of the Alban Hills.

Remains and archeology

In 1806 the first campaign of archaeological excavation on the top of the Tuscolo hill was begun by Lucien Bonaparte. In 1825 the archaeologist Luigi Biondi excavated to find out Tusculum, engaged by Queen Maria Cristina of Bourbon, wife of Charles Felix of Sardinia. In 1839 and 1840 the architect and archaeologist Luigi Canina, called by the same royal family, excavated the Theatre area of Tusculum. The ancient works of art excavated were sent to Savoy Castle of Agliè in Piedmont.

In 1825 Lucien Bonaparte found the so-called Tusculum portrait of Julius Caesar at the city's forum.[11]

In 1890 Thomas Ashby arrived to Rome as Director of the British School in Rome. He was an expert in ancient monuments topography and studied the Tusculum monuments, reporting the results in The Roman Campagna in Classical Times published in London in 1927. Earlier, he had described the remains thus in the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition:

On the hill of Tusculum itself are remains of a small theatre (excavated in 1839), with a reservoir behind it, and an amphitheatre. Both belong probably to the imperial period, and so does a very large villa (the substructures of which are preserved), by some attributed to Cicero, by others to Tiberius, near the latter. Between the amphitheatre and the theatre is the site of the Forum, of which nothing is now visible, and to the south on a projecting spur were tombs of the Roman period. There are also many remains of houses and villas.[12]

The citadel—which stood on the highest point an abrupt rock—was approached only on one side, that towards the city, and even here by a steep ascent of 150 feet. Upon it remains of the medieval castle, which stood here until 1191, alone are visible. The city walls, of which some remains still exist below the theatre, are built of blocks of the native lapis Albanus, or peperino. They probably belong to the Republican period. Below them is a well-house, with a roof formed of a pointed arch.[13]

Cicero's favourite residence and retreat for study and literary work was at, or near, Tusculum. It was here that he composed his celebrated Tusculan Disputations and other philosophical works. According to various parts of his works that it was a considerable building. It comprised two gymnasia with covered portions for exercise and philosophical discussion (Tusc. Disp. ii. 3). One of these, which stood on higher ground, was called the "Lyceum," and contained a library; the other, on a lower site, shaded by rows of trees, was called the "Academy." The main building contained a covered portion, or cloister, with recesses containing seats. It also had bathrooms, and contained a number of works of art, both pictures and statues in bronze and marble. The cost of this and the other house which he built at Pompeii led to him being burdened with debt.[13]

Modern archeology

In 1955 and 1956 the archaeologist Maurizio Borda excavated a necropolis with cinerary urns.

From 1994 to 1999 was held the last excavation campaigns of archaeologist Xavier Dupré and his staff undertaken by Escuela Espanola de Historia y Arqueologia en Roma.

Main sights

The Roman theatre on the hill of Tuscolo and the Villa of Tiberius were excavated between 1825 and 1841 and are now accessible.

In the High Middle Ages, there were three churches in Tusculum: St. Saviour and Holy Trinity "in civitate", and St. Thomas on the acropolis. The Greek monastery of St. Agatha lay at the foot of the Tuscolo hill, at the 15th mile of the Via Latina road, the old "Statio Roboraria" : it was founded in 370 AD by the basilian monk John of Cappadocia, a disciple of St. Basil of Caesarea, called St. Basil the Great. He brought here a relic of the master, handed it over to him by monk Gregory Nazianzus. Saint Nilus the Younger died in this Greek monastery on 27 December 1005.

The Portrait of "Madonna del Tuscolo", placed nowadays in a little aedicule on the Tuscolo hill, is a reproduction in ceramic of an earlier original icon from Tusculum, spoil of war, which now is in the Abbey of St. Mary in Grottaferrata.

In the extra-urban area located south of the city, between it and the Via Latina, there is archeological evidence of burials in the place of a medieval church already in ruin after 1191 and dating to the 13th century, found by the last archeological excavation (1999).[14]

The cross of Tusculum there was already in 1840, as reported by Cardinal Nicholas Wiseman, rector of the English College. In October, 1864 the students of the English College rebuilt the plinth of foundation of the old cross. Now on the top of the Tuscolo hill is an altar and an iron cross 19 metres (62,33 ft) high. The height of cross underlines the fact that it was built 19 centuries after the death of Jesus Christ.

Quotes

Strabo wrote about Tusculum in his Geography, V 3 § 12.:

But still closer to Rome than the mountainous country where these cities lie, there is another ridge, which leaves a valley (the valley near Algidum) between them and is high as far as Mount Albanus. It is on this chain that Tusculum is situated, a city with no mean equipment of buildings; and it is adorned by the plantings and villas encircling it, and particularly by those that extend below the city in the general direction of the city of Rome; for here Tusculum is a fertile and well-watered hill, which in many places rises gently into crests and admits of magnificently devised royal palaces.

References

- ^ Ellis Cornelia Knight (1805). Description of Latium: Or, La Campagna Di Roma. Longman, Hurst, Rees, and Orme. pp. 163–.

- ^ The Villa and Tomb of Lucullus at Tusculum, George McCracken, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 46, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1942), pp. 325-340

- ^ a b c d e f g Ashby 1911, p. 486.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 1.60

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.9

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.15

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.19-20

- ^ A History of Ancient Tusculum; George Englert McCracken Princeton University, 1934 pp 368-386

- ^ The Villa and Tomb of Lucullus at Tusculum, George McCracken, American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 46, No. 3 (Jul. - Sep., 1942), pp. 325-340 (16 pages)

- ^ Giuseppe Lugli, La villa di Domiziano sui Colli Albani: parte I, p 30

- ^ The J. Paul Getty Museum (1987). Ancient Portraits in the J. Paul Getty Museum: Volume 1. Getty Publications. p. 24. ISBN 0892360712.

- ^ Ashby 1911, pp. 486–487.

- ^ a b Ashby 1911, p. 487.

- ^ Scavi archeologici di Tusculum: rapporti preliminari delle campagne 1994-1999. Editorial CSIC - CSIC Press. 2000. pp. 538–. ISBN 978-88-900486-0-9.

Sources

- Richard Stillwell, ed. Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, 1976: "Tusculum, Latium, Italy"

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Ashby, Thomas (1911). "Tusculum". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 27 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 486–487.

- Cassius Dio. Roman History.

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus. The Roman Antiquities.

- Thietmar of Merseburg. Chronicle.

- Roger of Howden. Chronica.

- Gregorovius, Ferdinand. Rome in the Middle Ages Vol. IV Part 1. 1905.

- William Gell The Topography of Rome and its Vicinity with Map. 2 vols. London, 1834. [Rev. and enlarged by Edward Henry Banbury. London, 1846.]

- William Gell. Analisi storico-topografico-antiquaria della carta de' dintorni di Roma secondo le osservazione di Sir W. Gell e del professore A. Nibby. Rome, 1837 [2nd ed. 1848].

- Thomas Ashby. The Roman Campagna in Classical Times. London, 1927.

- G. Bagnani. The Roman Campagna and its treasures. London, 1929.

- G.E. Mc Cracken. A History of Ancient Tusculum. Washington, 1939.

- B. Goss. Tusculum" in PECS (Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites). 1976.

- T.J. Cornell. The beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to Punic War. London, 1995. ISBN 0-415-01596-0.

- Xavier Dupré. Scavi archeologici di Tusculum. Rome, 2000. ISBN 88-900486-0-3.

External links

- English translation of the Roman Antiquities - Dionysius of Halicarnassus (at LacusCurtius)

- Cassius Dio, Roman History (English translation on LacusCurtius)

- Quilici, L., S. Quilici Gigli, R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies. "Places: 423108 (Tusculum)". Pleiades. Retrieved March 8, 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)