1988 Pacific hurricane season

| 1988 Pacific hurricane season | |

|---|---|

Season summary map | |

| Seasonal boundaries | |

| First system formed | June 15, 1988 |

| Last system dissipated | November 2, 1988 |

| Strongest storm | |

| Name | Hector |

| • Maximum winds | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-minute sustained) |

| • Lowest pressure | 935 mbar (hPa; 27.61 inHg) |

| Seasonal statistics | |

| Total depressions | 23 |

| Total storms | 15 |

| Hurricanes | 7 |

| Major hurricanes (Cat. 3+) | 3 |

| Total fatalities | 24 total |

| Total damage | Unknown |

| Related articles | |

The 1988 Pacific hurricane season was the least active Pacific hurricane season since 1981. It officially began May 15, in the eastern Pacific, and June 1, in the central Pacific and lasted until November 30. These dates conventionally delimit the period of each year when most tropical cyclones form in the northeastern Pacific Ocean. The first named storm, Tropical Storm Aletta, formed on June 16, and the last-named storm, Tropical Storm Miriam, was previously named Hurricane Joan in the Atlantic Ocean before crossing Central America and re-emerging in the eastern Pacific; Miriam continued westward and dissipated on November 2.

The season produced 23 tropical depressions, of which 15 attained tropical storm status. Seven storms reached hurricane status, three of which became major hurricanes. The strongest storm of the season, Hurricane Hector, formed on July 30 to the south of Mexico and reached peak winds of 145 mph (233 km/h)—Category 4 status—before dissipating over open waters on August 9; Hector was never a threat to land. Tropical Storm Gilma was the only cyclone in the season to make landfall, crossing the Hawaiian Islands, although there were numerous near-misses. Gilma's Hawaiian landfall was unusual, but not unprecedented. There were also two systems that successfully crossed over from the Atlantic: the aforementioned Joan / Miriam and Hurricane Debby, which became Tropical Depression Seventeen-E, making the 1988 season the first on record in which more than one tropical cyclone has crossed between the Atlantic and Pacific basins intact.[1] Three systems caused deaths: Tropical Storm Aletta caused one death in southwestern Mexico, Hurricane Uleki caused two drownings off the coast of Oahu as it passed by the Hawaiian Islands, and Hurricane Kristy caused 21 deaths in the Mexican states of Oaxaca and Chipas.

Seasonal summary

The accumulated cyclone energy (ACE) index for the 1988 Pacific hurricane season was 127.45 units (87.79 units from the Eastern Pacific and 39.66 units from the Central Pacific).[2]

The total tropical activity in the season was below-average. There were 13 cyclones in the Eastern Pacific, as well as two in the Central. Of the 15 cyclones, one crossed from the Atlantic Ocean into the Pacific, and another moved from the Central Pacific to the Western Pacific. In the Eastern Pacific, there were seven cyclones peaking as a tropical storm, and six hurricanes, of which two reached Category 3 intensity or higher on the Saffir–Simpson scale. A tropical storm and a major hurricane occurred in the Central Pacific.[3]

Tropical Storm Gilma made the only landfalls of the season in the Hawaiian Islands, causing some rainfall, but no direct deaths or damage occurred as a result of it.[4][5] These were the only landfalls in the season that were made, which is unusual as most landfalls in the Eastern Pacific occur on the Mexican coast. This is due to the closeness of the Mexican region to the major source of tropical activity to the west of Central America.[6] Hurricane Uleki, the strongest hurricane in the Central Pacific region during the season, caused two drownings in Oahu and heavy waves hit the coast of the Hawaiian Islands.[7] Tropical Storm Miriam, the last storm of the season, formed as a result of Hurricane Joan from the Atlantic, and flooding resulted in parts of Central America, due to heavy rainfall.[8]

Systems

Tropical Depression One-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 15 – June 18 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1005 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical disturbance organized into the first eastern Pacific tropical depression of the season on June 15. A convective band on the north and west sides of the system became well-defined, and anticyclonic outflow allowed for initial organization.[9] After forming, the depression tracked west-southwestward and intensified due to disrupted outflow from a large air stream disturbance.[10] On June 16, strong convection with spiral banding developed over the depression, although it failed to strengthen further.[11][12] A low-pressure l northwest of the depression in combination with Tropical Storm Aletta to the northeast caused the depression to weaken, and it dissipated on June 18.[13]

Tropical Storm Aletta

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 16 – June 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 992 mbar (hPa) |

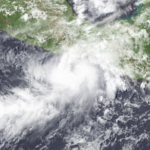

A tropical wave moved off the coast of Africa and progressed westward through the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean, before crossing over Central America on June 13 and emerging into the warm waters of the east Pacific on June 14. Shortly after, satellite imagery showed good upper-level outflow, although cloud banding remained disorganized. On June 16, the broad circulation better organized on the northeastern section, with deep convection developing. A tropical depression formed later that day about 200 miles (320 km) to the southeast of Acapulco, Mexico. It developed further as it moved northward toward the southwest coast of Mexico, and had organized sufficiently to be named Tropical Storm Aletta on June 17. The cyclone drifted north-northwest for the next 36 hours before turning westward, parallel to the Mexican coast. The storm began to lose its convection on June 19 and weakened into a tropical depression later that day. The depression weakened further into a weak low-level circulation before dissipating on June 21.[14] Although Aletta approached the Acapulco area of the Mexican coast, it did not make landfall. The portion of coast affected by Aletta received heavy rainfall; unofficial reports state that one person died as a result of the storm, and the storm produced some damage due to rainfall and flooding.[15]

Tropical Storm Bud

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | June 20 – June 22 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

Satellite imagery first detected a low-level circulation on June 20, associated with some heavy convection, 200 miles (320 km) south of the Mexico–Guatemala border, and it intensified into a tropical depression. The cyclone moved northwest then west-northwest over two days. A 40 mph (64 km/h) wind report from a ship on June 21 allowed the depression to be upgraded to Tropical Storm Bud later that day. For the next day, the low-level circulation moved away from its deep convection, dissipating near Acapulco, Mexico. A portion of Bud remaining over land may have been part of the reason for the lack of strengthening of the cyclone.[16]

Tropical Depression Four-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 2 – July 4 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A system developed in the eastern Pacific, and later strengthened into a tropical depression on July 1, when it obtained a better defined low-level circulation. The center was exposed, with little convection on the northeast side, due to shear aloft.[17] The system moved to the northwest, while shear continued to move the deep convection of the cyclone to the southwest of its center of circulation.[18] The circulation completely lacked deep convection late on July 2, although it continued to have a well-defined low-level center.[19] The depression drifted slowly northward, located south of Baja California, before dissipating just south of the peninsula on July 4, with no circulation or deep convection detected.[20][21] A small amount of associated rainfall affected Baja California, as the cyclone passed near the peninsula.[22]

Hurricane Carlotta

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 8 – July 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 75 mph (120 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the western coast of Africa on June 23, and for the next two weeks, moved through the tropical waters of the Atlantic Ocean and later crossed Central America. It began developing further when it entered the Pacific Ocean and became a dense area of moisture and cloudiness. The wave developed into a disturbance on July 8, and attained tropical depression status in the afternoon on July 8, south of Mexico. After entering a favorable area of warm waters, the depression strengthened to Tropical Storm Carlotta on July 9. Carlotta continued to develop, reached peak strength, and developed into Hurricane Carlotta on July 11.[23] During the duration of the storm, Carlotta was not considered a hurricane, however after post-season reanalysis Carlotta's strength was upgraded to minimal hurricane status.[24] As it moved into less favorable conditions it lost strength and weakened to a tropical storm on July 12. Carlotta began to lose its deep convection, and weakened into a tropical depression on July 13 as it moved into cooler waters. It later moved west-southwest and dissipated on July 15.[23]

Tropical Storm Daniel

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 19 – July 26 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 65 mph (100 km/h) (1-min); 994 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave moved off the coast of northwestern Africa on July 4, and moved through tropical regions of the northern Atlantic and Caribbean without the indication of development. The tropical disturbance crossed Central America on July 14, and from then until July 18, the westward motion decreased, as convection and organization increased over warm waters. It developed into a tropical depression on July 19, and into Tropical Storm Daniel 600 miles (970 km) southwest of the southern tip of Baja California on July 20. A high pressure system over the western United States and northern Mexico forced Daniel and an upper-level low on parallel west-northwest paths. Daniel stayed generally the same strength for the next few days, reaching peak strength on July 23. Daniel declined into a tropical depression on July 25 and dissipated on July 26.[25]

Tropical Storm Emilia

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 27 – August 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 992 mbar (hPa) |

On July 15, a tropical wave exited Africa and crossed the Atlantic Ocean. It crossed into the Pacific Ocean on July 24, developing convection and outflow. On July 27, it organized into a tropical depression off the southwest coast of Mexico.[26] Continuing generally westward, the thunderstorm activity fluctuated,[27] and slowly developing, it intensified into Tropical Storm Emilia on July 29.[26] The storm attained peak winds of 70 mph (110 km/h) on July 30,[26] although wind shear and interaction with nearby Tropical Storm Fabio prevented further intensification; the low-level circulation was located along the northwest edge of the deepest convection.[28][29] It became disorganized and difficult to locate on satellite imagery,[30] and soon the circulation was exposed from the thunderstorms.[31] On August 1, Emilia weakened to tropical depression status, and late on August 2, the last advisory was issued as the system had become very disorganized with minimal convection.[26][32] Its remnants were tracked for the next few days, and although some deep convection returned momentarily, the system's convection soon disappeared.[26]

Hurricane Fabio

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 28 – August 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 140 mph (220 km/h) (1-min); 943 mbar (hPa) |

A well-organized ITCZ disturbance with deep convection organized further over the northeastern Pacific Ocean on July 28.[24][33] It developed into a tropical depression later that day, while 1,000 miles (1,600 km) southwest of the southern tip of Baja California.[33] The position of Fabio's formation was much further south and west than where most tropical cyclones form during the same time period.[24] The depression moved westward while gradually strengthening and it developed into Tropical Storm Fabio on July 29. It intensified further over the next few days and it intensified into a hurricane on July 31. The system increased its speed as it steadily strengthened further. A trough turned the storm west-northwestward on August 3. Satellite estimates indicated that Fabio reached its maximum intensity later on August 3, with a well-defined eye with very deep convection surrounding it. The Central Pacific Hurricane Center issued a tropical storm watch for the Big Island on August 4, due to the threatening west-northwest turn towards it. However, the retreat of a trough later turned Fabio back to the west and the CPHC discontinued the tropical storm watch on August 5.[33] Fabio's good upper-level conditions later weakened and began to lose its convection over cooler waters.[24] Fabio quickly weakened and it weakened into a tropical storm again later on August 5, and back to a depression on August 6. The depression turned west-northwestward again on August 8, but Fabio dissipated on August 9.[33] As the cyclone moved near the Hawaiian islands, heavy rainfall fell across the chain, peaking at 18.75 in (476 mm) near Pāpa'ikou on the island of Hawaii.[34]

Tropical Depression Nine-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 28 – July 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 30 mph (45 km/h) (1-min); 1006 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression developed in the eastern Pacific on July 28, forecast to be absorbed by a very close nearby depression, later Tropical Storm Gilma.[35] The depression moved northward, although in unfavorable conditions.[36] The cyclone weakened as the depression to the southwest strengthened further. Limited deep convection developed with the system, although the cyclone continued in unfavorable conditions with shearing.[37] Visible satellite imagery later showed a very weak system, and the storm dissipated on July 29.[38]

Tropical Storm Gilma

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 28 – August 3 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 50 mph (85 km/h) (1-min); 1000 mbar (hPa) |

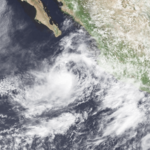

A wave that previously moved through the Atlantic from the northwest coast of Africa, crossed over Central America into the Pacific on July 17 or July 18. On July 19, this disturbance was 700 miles (1,100 km) to the southeast of the developing Tropical Storm Daniel. The system moved westward for the following week without any signs of intensification. However, on July 26 and 27, the system appeared to be strengthening due to a banding pattern. By July 28, the convection underwent further organization with some weak outflow high in the storm. It developed into a tropical depression later on July 28, much further west then most east Pacific storms develop at. For the next day the cyclone remained fairly stationary, but began to strengthen over warm waters. On July 29 the depression strengthened into Tropical Storm Gilma, based on satellite imagery. Limited intensification followed, due to shear high in the storm. It weakened a tropical depression again on July 30, due to weakness depicted in satellite imagery. Gilma then moved west-northwestward through the northeast Pacific. The depression skirted the Hawaiian Islands, but dissipated near Oahu on August 3.[4] On the Hawaiian Islands there were no direct damage or deaths, although some rainfall occurred on the islands.[5]

Hurricane Hector

| Category 4 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | July 30 – August 9 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 145 mph (230 km/h) (1-min); 935 mbar (hPa) |

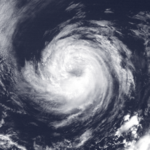

A tropical depression formed on July 30, while 400 miles (640 km) south of Acapulco, Mexico. The depression tracked west-northwestward, becoming Tropical Storm Hector on July 31. Its west-northwest motion continued, due to an area of high pressure to its north, and Hector intensified into a hurricane on August 2. Based on satellite data, the hurricane is estimated to have reached its peak intensity of 145 mph (233 km/h) on August 3; this made Hector a Category 4 hurricane on the Saffir–Simpson scale, which was the strongest storm of the season. Hector began to move due west on August 5 and it had already begun weakening. The storm continued westward increasing its forward speed. On August 6 it had appeared Hector had strengthened, but steadily weakened afterwards and finally dissipated on August 9, while 650 miles (1,050 km) east of Hilo, Hawaii. Hector was never a threat to land.[39]

Hurricane Iva

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 5 – August 13 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 968 mbar (hPa) |

A wave that first came off the northwest coast of Africa moved through the Atlantic, before entering the East Pacific on August 4. The wave developed more organized convection when it entered the region, and it turned into a tropical depression on August 5, while 165 miles (266 km) south of Oaxaca, Mexico.[24][40] It developed into Tropical Storm Iva on August 6. Iva turned on a west-northwestward course and continued strengthening, before it developed into a hurricane on August 7. The cyclone moved northwestward after becoming a hurricane, and satellites estimate it reached peak intensity on August 8. On the same day Iva passed within 50 miles (80 km) of Socorro Island. Winds of 45 mph (72 km/h) were reported on the island along with moderate rain. The storm moved through cooler waters for the next day, and began to weaken. Iva declined into a tropical storm again on August 9, and by August 10 the cyclone lost its deep convection along with organization. It intensified into a tropical depression again on August 11, and moved southwest due to a high pressure before dissipating on August 13.[40]

Tropical Depression Thirteen-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 14 – August 16 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1007 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed on August 12, with movement towards the west-northwest.[41] It continued toward the west-northwest, near the circulation of Tropical Storm Iva.[42] The low-level circulation of the cyclone was displaced to the east of the deep convection, and the system moved to the northwest.[43] The depression lost much of its convection later on August 13, and it had a less defined center.[44][45] The cyclone turned to the south, and lost its associated deep convection.[46] Some weak convection redeveloped near the center, but the depression dissipated later on August 14.[47][48]

Tropical Storm John

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 16 – August 21 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

A disturbance that passed off the northwestern African coast on August 3 crossed the Atlantic Ocean, before entering into the Pacific. A tropical depression formed in the East Pacific on August 16, 150 miles (240 km) southwest of Manzanillo, Mexico, based on satellite estimates. The cyclone progressed slowly northwestward, and intensified Tropical Storm John on August 17, less than 24 hours after its formation. John continued northwest for a short while, before the low-level center of circulation had been exposed. John degenerated to a tropical depression on August 18 due to a lack of convection, made a loop while less than 100 miles (160 km) south of the southern tip of Baja California. It shortly became a little better organized after completing the loop on August 20, but John dissipated on August 21, southwest of Baja California, due to shearing and cold waters. Its remnants continued northwestward parallel to the southwest coast of Baja California. John caused no reported deaths or damage.[49]

Tropical Depression Fifteen-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 27 – August 29 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1004 mbar (hPa) |

On August 26, a disturbance south of Baja California organized into Tropical Depression Fifteen-E. Initially, the system moved northwest towards cooler waters[50] as the location of the low-level circulation was to the southwest of the deep convection associated with the cyclone.[51] The center drifted to the east of the small area of concentrated convection, and its intensity remained steady.[52] It weakened and became loosely defined due to upper-level wind shear, and the storm lost all of its convection before dissipating and degenerating into a low-level swirl.[53][54]

Hurricane Uleki

| Category 3 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 28 – September 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 125 mph (205 km/h) (1-min); 957 mbar (hPa) |

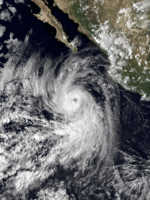

Towards the end of August, tropical activity in the ITCZ southeast of the Hawaiian Islands began to be monitored. On August 28, this tropical disturbance organized into a tropical depression, as it was located about 800 miles (1,300 km) southeast of the Big Island. It intensified at a fair rate, and intensified Tropical Storm Uleki the next day. It continued to strengthen, and reached hurricane intensity on August 31. It moved slowly west-northwest until steering currents collapsed on September 1. Now a Category 3 hurricane, Uleki slowly edged north towards the Hawaiian Islands. After looping, Uleki resumed its westward path on September 4. Its stalling in the ocean had weakened it, and the hurricane passed midway between Johnston Island and French Frigate Shoals. Uleki crossed the dateline on September 8. It turned slightly to the north and meandered in the open Pacific days until it dissipated on September 14.[7]

As Uleki drifted towards the Hawaiian Islands, tropical storm watches were issued for Oahu, Kauai, and Niihau on September 3. In addition, reconnaissance missions were flown into the hurricane. Uleki caused heavy surf on the Hawaiian Islands, that being its only significant effect. This heavy surf flooded the southeastern runway on Midway Island, and produced two drownings on Oahu.[7] Nineteen people were also rescued from rough surf, with five- to six-foot (1.5 to 1.8 meter) waves, off the coast of beaches in Hawaii.[55]

Hurricane Kristy

| Category 1 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | August 29 – September 6 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 90 mph (150 km/h) (1-min); 976 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical wave passed off the northwestern coast of Africa on August 6. It did not develop as it passed through the Atlantic Ocean, until August 19 when convection began to form. On August 20 the disturbance turned into Tropical Depression Six in the Atlantic basin. It passed from the Leeward Islands up to the central Caribbean, until it dissipated on August 23. As it passed over Central America, the disturbance had little remaining convection. However, the convection associated with the system began to organize when it entered the Pacific, and it strengthened into a tropical depression on August 29, while located 300 miles (480 km) south-southeast of Acapulco, Mexico. Later that day the depression intensified into Tropical Storm Kristy, based on ship reports of tropical storm force winds. Kristy strengthened into a hurricane on August 31, based solely on satellite imagery. Hurricane Kristy had short lifespan though, and weakened to a tropical storm on September 2. The easterly shear associated with an anticyclone south of Baja California, which caused Kristy's convection to be forced west of the low-level center of the system, and therefore weakened it. Kristy weakened further to a depression on September 3, and weak steering currents allowed the cyclone to remain stationary on September 4, loop the following day, and then began to move eastward. The depression dissipated on September 6.[56][57]

Although the storm passed relatively close to the coast, no tropical cyclone warnings and watches were required as the storm remained offshore.[56] However, Kristy produced heavy rains and widespread flooding in the Mexican states of Chiapas and Oaxaca; as a result, several rivers overflowed their banks. Thousands of tourists were stranded from the beaches.[56][58] At least 21 deaths were attributed to Kristy: 16 in Oaxaca and 5 in Chiapas.[59] More than 20,000 people in the former were evacuated from their homes; consequently, a state of emergency was declared.[57] The outer rainbands of Kristy delayed the rescue of the victims of a Brazilian-made aircraft that crashed west of the Sierra Madre Occidental mountain range.[60] No official damage figures were reported by the Mexican government.[57]

Tropical Depression Seventeen-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 6 – September 8 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1002 mbar (hPa) |

The remnants of Hurricane Debby moved over the mountainous areas of Mexico, passing into the Pacific from the Pacific coast of Mexico near Manzanillo. The disturbance moved towards the north-northwest and organized into a tropical depression on September 6 just south of the Gulf of California.[61] The cyclone remained stationary due to weak low-level steering currents, later drifting to the north-northwest with an area of deep convection causing rain on the Mexican coast.[62][63] It later moved to the northwest, with partial exposure of the center of the system, and with some shear still affecting it.[64] The cyclone continued to have shear over the system, which caused it not to strengthen, and its movement became nearly stationary.[65] After remaining stationary longer, the system dissipated as a low-level swirl.[66]

Tropical Depression Eighteen-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 12 – September 15 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1003 mbar (hPa) |

A disturbance organized, and based on satellite imagery it strengthened into a tropical depression on September 12.[67] The center of circulation remained on the eastern fringe of its deep convection and the storm moved west or west-northwestward.[68] On September 13, the depression underwent shearing, while its low-level circulation center had only a small amount of deep convection associated with it.[69] The cyclone became poorly defined, and its movement turned stationary on September 14.[70] The low-level circulation of the system remained visible, even though it weakened due to shearing. Little deep convection remained associated with the system, and the cyclone stayed stationary.[71] The depression having no remaining convection and having become just a low-level cloud swirl, dissipated on September 15.[72]

Tropical Storm Wila

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 21 – September 25 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 40 mph (65 km/h) (1-min); 1001 mbar (hPa) |

A tropical depression formed on September 21 as an area of deep convection. The cyclone organized slowly though, drifting slowly, initially west then to the northwest. However, the depression recurved northeast, due to a trough. As the cyclone moved northeast, the system strengthened as indicated by an Air Force reconnaissance plane showing tropical storm force winds. It therefore intensified into Tropical Storm Wila on September 25. Wila, however, weakened within a day, and therefore became a tropical depression. The remnant low of Wila produced some heavy rain over the Hawaiian Islands on September 26 and 27.[7]

Hurricane Lane

| Category 2 hurricane (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | September 21 – September 30 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 105 mph (165 km/h) (1-min); 970 mbar (hPa) |

A wave moved westward off the coast of Africa, passed through the Caribbean, and into the ITCZ of the eastern Pacific on September 20. The system developed organized deep convection, and strengthened into a tropical depression on September 21, while 300 miles (480 km) southeast of Acapulco, Mexico. As the low-level circulation organized further in the depression it intensified into Tropical Storm Lane, later on September 21. Lane developed further with an upper-level outflow pattern, and the cyclone turned into a hurricane on September 23. Later on September 23 and on September 24, an eye appeared on satellite imagery. A trough to the northwest of Lane disturbed its upper-level outflow on September 24. Diminishing convection and loss of its eye caused Lane to weaken to a tropical storm on September 27, and into a depression on September 28. Later on September 28, the cyclone moved into cooler waters and Lane lost nearly all of its deep convection. It weakened into a low-level swirl, and Lane dissipated on September 30. Lane caused no reported casualties or damage.[73][74]

Tropical Depression Twenty-E

| Tropical depression (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 11 – October 12 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 35 mph (55 km/h) (1-min); 1008 mbar (hPa) |

The remnants of Atlantic basin Tropical Storm Isaac moved into the eastern Pacific. These remnants underwent better organization and strengthened into a tropical depression on October 11 south of Baja California.[75][76] Strong vertical southwesterly wind shear affected the cyclone, with the center of circulation later seen on the west side of the lessening amount of deep convection.[77] The system remained poorly organized and had trouble strengthening to this continual poor organization as it moved westward.[78] The system could not be located on satellite imagery and therefore dissipated on October 12.[79]

Tropical Storm Miriam

| Tropical storm (SSHWS) | |

| Duration | October 23 (Entered basin) – November 2 |

|---|---|

| Peak intensity | 70 mph (110 km/h) (1-min); 986 mbar (hPa) |

Atlantic Hurricane Joan survived the passage over Central America and entered the Pacific, although greatly weakened. Following the policy at the time, Joan was renamed Miriam.

Miriam brought heavy rains to parts of Central America. Isolated flooding and mudslides happened, although casualties and damage reports are not available.[8] 10.37 in (263 mm) of rain fell in Kantunilkin/Lázaro Cárdenas, Mexico as a result of Miriam and the former Joan.[34] Guatemala's ports along its Pacific coast were closed and people in El Salvador were evacuated from low-lying areas due to the storm.[80] Miriam then turned away from Central America and weakened to a depression. The depression survived for over a week until it dissipated on October 30. Tropical Depression Miriam's remnants regenerated the next day, and Miriam finally dissipated on November 2.[8]

Storm names

The following list of names was used for named storms that formed in the North Pacific Ocean east of 140°W in 1988.[81] This is essentially the same list used in the 1982 season, though the rotating lists went only to the "W" name at the time.[82]

|

|

|

For storms that form in the North Pacific from 140°W to the International Date Line, the names come from a series of four rotating lists. Names are used one after the other without regard to year, and when the bottom of one list is reached, the next named storm receives the name at the top of the next list.[81] Two named storms, listed below, formed within the area in 1988. Named storms in the table above that crossed into the area during the season are noted (*).[7]

|

|

Retirement

The World Meteorological Organization retired the name Iva from the rotating Eastern Pacific name lists after the 1988 season.[83] It was replaced with Ileana for the 1994 season.[84]

Season effects

This is a table of all of the storms that formed in the 1988 Pacific hurricane season. It includes their name, duration (within the basin), peak classification and intensities, areas affected, damage, and death totals. Deaths in parentheses are additional and indirect (an example of an indirect death would be a traffic accident), but were still related to that storm. Damage and deaths include totals while the storm was extratropical, a wave, or a low, and all of the damage figures are in 1988 USD.

| Saffir–Simpson scale | ||||||

| TD | TS | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

| Storm name |

Dates active | Storm category at peak intensity |

Max 1-min wind mph (km/h) |

Min. press. (mbar) |

Areas affected | Damage (USD) |

Deaths | Ref(s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| One-E | June 15–18 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1005 | None | None | None | |||

| Aletta | June 16–21 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 992 | Southwestern Mexico | Minor | 1 | |||

| Bud | June 20–22 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | Southwestern Mexico | None | None | |||

| Four-E | July 2–4 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1007 | None | None | None | |||

| Carlotta | July 8–15 | Category 1 hurricane | 75 (120) | 994 | None | None | None | |||

| Daniel | July 19–26 | Tropical storm | 65 (100) | 994 | None | None | None | |||

| Emilia | July 27 – August 2 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 992 | None | None | None | |||

| Fabio | July 28 – August 9 | Category 4 hurricane | 140 (220) | 943 | Hawaii | None | None | |||

| Nine-E | July 28–29 | Tropical depression | 30 (45) | 1006 | None | None | None | |||

| Gilma | July 28 – August 3 | Tropical storm | 50 (85) | 1000 | Hawaii | None | None | |||

| Hector | July 20 – August 9 | Category 4 hurricane | 145 (230) | 935 | None | None | None | |||

| Iva | August 5–13 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 968 | None | None | None | |||

| Thirteen-E | August 14–16 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1007 | None | None | None | |||

| John | August 16–21 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Fifteen-E | August 27–29 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1004 | None | None | None | |||

| Uleki | August 28 – September 8 | Category 3 hurricane | 125 (205) | 957 | Hawaii | None | 2 | |||

| Kristy | August 29 – September 6 | Category 1 hurricane | 90 (150) | 976 | Western Mexico | Unknown | 21 | |||

| Seventeen‑E | September 6–8 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1002 | Western Mexico | None | None | |||

| Eighteen-E | September 12–15 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1003 | None | None | None | |||

| Wila | September 21–25 | Tropical storm | 40 (65) | 1001 | None | None | None | |||

| Lane | September 21–30 | Category 2 hurricane | 105 (165) | 970 | None | None | None | |||

| Twenty-E | October 11–12 | Tropical depression | 35 (55) | 1008 | None | None | None | |||

| Miriam | October 23 – November 2 | Tropical storm | 70 (110) | 986 | Central America, Southern Mexico (after crossover) | Minimal | None | |||

| Season aggregates | ||||||||||

| 23 systems | June 15 – November 2 | 145 (230) | 935 | Unknown | 24 | |||||

See also

- List of Pacific hurricanes

- Pacific hurricane season

- 1988 Atlantic hurricane season

- 1988 Pacific typhoon season

- 1988 North Indian Ocean cyclone season

- South-West Indian Ocean cyclone seasons: 1987–88, 1988–89

- Australian region cyclone seasons: 1987–88, 1988–89

- South Pacific cyclone seasons: 1987–88, 1988–89

References

- ^ Henson, Bob (October 10, 2022). "As Julia fades, floods plague Central America". New Haven, Connecticut: Yale Climate Connections. Retrieved October 13, 2022.

- ^ National Hurricane Center; Hurricane Research Division; Central Pacific Hurricane Center (April 26, 2024). "The Northeast and North Central Pacific hurricane database 1949–2023". United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 29, 2024. A guide on how to read the database is available here.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (1996). "Average Cumulative Number of Systems Per Year". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ^ a b BMM (1988). "Tropical Storm Gilma Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ a b BMM (1988). "Tropical Storm Gilma Prelim 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ Centro de Ciencias de la Atmósfera (2003). "Climatology of landfalling hurricanes and tropical storms in Mexico" (PDF). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2008-03-12.

- ^ a b c d e The 1988 Central Pacific Tropical Cyclone Season (Report). Central Pacific Hurricane Center. 1988. Archived from the original on 2018-09-29. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- ^ a b c Harold P. Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Storm Miriam Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression One-E Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ^ Clark (1988). "Tropical Depression One-E Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression One-E Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ^ Clark (1988). "Tropical Depression One-E Discussion Seven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ^ Case (1988). "Tropical Depression One-E Discussion Fourteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ^ Harold P. Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Storm Aletta Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ Harold P. Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Storm Aletta Prelim 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ Miles Lawrence (1988). "Tropical Storm Bud Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Four-E Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Case (1988). "Tropical Depression Four-E Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Four-E Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Four-E Discussion Nine". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Case (1988). "Tropical Depression Four-E Discussion Ten". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Four-E Advisory Nine". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-03.

- ^ a b RAC/BAM (1988). "Tropical Storm Carlotta Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ^ a b c d e Gerrish, Harold P.; Mayfield, Max (1988). "Eastern North Pacific Tropical Cyclones of 1988". Monthly Weather Review. 117 (10): 2266–2277. Bibcode:1989MWRv..117.2266G. doi:10.1175/1520-0493(1989)117<2266:ENPTCO>2.0.CO;2.

- ^ GBC (1988). "Tropical Storm Daniel Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ^ a b c d e Jim Gross (1988). "Tropical Storm Emilia Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-26.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression Seven-E Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ Case (1988). "Tropical Storm Emilia Discussion Ten". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-09-14.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Storm Emilia Discussion Eleven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Case (1988). "Tropical Storm Emilia Discussion Sixteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Case (1988). "Tropical Storm Emilia Discussion Seventeen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ Case (1988). "Tropical Depression Emilia Discussion Twenty-Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2008-09-16.

- ^ a b c d BMM (1988). "Tropical Storm Fabio Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ^ a b Roth, David M. (January 3, 2023). "Tropical Cyclone Point Maxima". Tropical Cyclone Rainfall Data. United States Weather Prediction Center. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Case (1988). "Tropical Depression Nine-E Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression Nine-E Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Nine-E Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Nine-E Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- ^ MBL (1988). "Hurricane Hector Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ a b RAC (1988). "Hurricane Iva Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ National Weather Service (1988). "Tropical Depression Thirteen-E Marine Advisory Twelve". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Thirteen-E Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Thirteen-E Discussion Four". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Thirteen-E Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Thirteen-E Discussion Seven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression Thirteen-E Discussion Ten". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Thirteen-E Discussion Eleven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Thirteen-E Discussion Eleven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-06.

- ^ GBC (1988). "Hurricane John Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Fifteen-E Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression Fifteen-E Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression Fifteen-E Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Sheets (1988). "Tropical Depression Fifteen-E Discussion Eight". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Lawrence (1988). "Tropical Depression Fifteen-E Discussion Nine". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Bruce Dunford (September 3, 1988). "Hurricane Near Hawaii Weakens, Easing Threat". Honolulu, Hawaii. Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ^ a b c Jim Gross (1988). "Hurricane Kristy Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ a b c Jim Gross (1988). "Hurricane Kristy Prelim 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Kiel, Fredrick (September 6, 1988). "Hurricane, Storm kill 48 in Mexico". Schenectady Gazette. United Press International. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ Lindajoy Fenley (September 8, 1988). "New Tropical Storm Forms As Mexico Mops Up". Mexico City, Mexico. Associated Press. – via Lexis Nexis (subscription required)

- ^ "21 people reported dead in plane crash". Tri-City Herald. Associated Press. September 1, 1988. p. 56. Retrieved June 9, 2012.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Seventeen-E Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Seventeen-E Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Lawrence (1988). "Tropical Depression Seventeen-E Discussion Three". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Clark (1988). "Tropical Depression Seventeen-E Discussion Four". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Seventeen-E Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression Seventeen-E Discussion Nine". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-07.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Eighteen-E Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Eighteen-E Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Eighteen-E Discussion Six". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Lawrence (1988). "Tropical Depression Eighteen-E Discussion Seven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression Eighteen-E Discussion Twelve". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Mayfield (1988). "Tropical Depression Eighteen-E Discussion Thirteen". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ BMM (1988). "Hurricane Lane Prelim 1". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ BMM (1988). "Hurricane Lane Prelim 2". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-09-30.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Twenty-E Discussion One". National Hurricane Center. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Gerrish (1988). "Tropical Depression Twenty-E Public Advisory One". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Gross (1988). "Tropical Depression Twenty-E Discussion Two". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Clark (1988). "Tropical Depression Twenty-E Discussion Five". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ Clark (1988). "Tropical Depression Twenty-E Discussion Seven". National Hurricane Center. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

- ^ "Joan downgraded, but still packs punch". Frederick News-Post. Associated Press. 1988. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- ^ a b National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1988. pp. 3-6, 8–9. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1982. p. 3-8. Retrieved January 14, 2024.

- ^ "Tropical Cyclone Naming History and Retired Names". Miami, Florida: National Hurricane Center. Retrieved January 17, 2024.

- ^ National Hurricane Operations Plan (PDF) (Report). Washington, D.C.: NOAA Office of the Federal Coordinator for Meteorological Services and Supporting Research. May 1994. p. 3-8. Retrieved February 5, 2024.