Tower Hill State Park

| Tower Hill State Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category V (protected landscape/seascape) | |

The shot tower overlooking the Wisconsin River Valley | |

| Location | Iowa, Wisconsin, United States |

| Coordinates | 43°8′48″N 90°2′55″W / 43.14667°N 90.04861°W |

| Area | 77 acres (31 ha) |

| Established | 1922 |

| Governing body | Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources |

Shot Tower | |

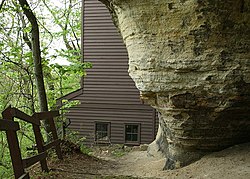

The base of the shot tower, where the shaft starts | |

| Location | SE of Spring Green in Tower Hill State Park |

|---|---|

| Built | 1831–1833 |

| NRHP reference No. | 73000080 |

| Added to NRHP | April 3, 1973 |

Tower Hill State Park is a state park of Wisconsin, United States, which contains the reconstructed Helena Shot Tower. The original shot tower was completed in 1832 and manufactured lead shot until 1860. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973.[1][2] The park abuts the Wisconsin River and is bordered by state-owned land comprising the Lower Wisconsin State Riverway.

Natural history

The bluffs along the Wisconsin River are formed of Jordan Sandstone. The park lies within the Driftless Area, a region of the American Midwest that remained ice-free through three successive ice ages.[3] In the 19th century the Wisconsin River flowed directly past the base of the bluffs. The river has since shifted slightly, and a stream known as Mill Creek marks the northern boundary of the park.

History of the shot tower

Shot towers harness the effects of surface tension on liquids in free-fall, a technique developed in 1782. Molten lead can be poured through a strainer at the top of a tower or shaft. The droplets become spherical as they fall and cool in this shape during their descent. The pellets are caught in a water basin to break their fall and finish cooling.

In 1830 a businessman from Green Bay, Wisconsin, named Daniel Whitney was traveling along the Wisconsin River and recognized a sharp bluff near the town of Helena as a promising location for a shot tower. Lead deposits had recently been discovered in several locations around Iowa County. From the top of the bluff there was a 60-foot (18 m) sheer drop, below which the sandstone cliff sloped down to the riverbank, 180 feet (55 m) below the clifftop. Whitney formed the Wisconsin Shot Company with some other investors, and set his employee John Metcalf to oversee construction.[4]

The 60-foot (18 m) cliff was a convenient headstart, but Metcalf needed someone to continue a shaft for the remaining 120 feet (37 m) to ground level. Access to the bottom of the shaft, where the lead shot would be collected, necessitated a 90-foot (27 m) horizontal tunnel. In 1831 Thomas B. Shaunce, a 22-year-old lead miner in Galena, Illinois, was hired for the task.

Shaunce worked mostly alone but received some assistance from a friend named Malcom Smith. They dug with pickaxes and a gad, using gunpowder to loosen the harder rock of the lower layers. Shaunce used a plumb-bob to ensure that he was keeping the shaft perfectly straight, and a windlass to haul out the broken rock. Shaunce calculated where to begin digging the horizontal tunnel by standing across the water and sighting with his rifle directly below the top of the shaft. He dug in from the riverbank, using a line of stakes to maintain his alignment. When he first broke through from the horizontal tunnel to the bottom of the shaft, a blast of air knocked Shaunce unconscious and collapsed one of his lungs.[5]

The project took 187 working days, interrupted in the spring of 1832 when Shaunce and Smith both returned to Galena and enlisted in the Illinois Militia to fight in the Black Hawk War. Shaunce had been contracted to be paid $1000 for his work, but was ultimately offered land instead.[5]

A smelting house was built at the top of the cliff, and the 60-foot (18 m) drop from there to the opening of Shaunce's tunnel was enclosed with a wooden shaft. A finishing house was built on the riverbank, where the shot was dried, graded, and sorted. This was joined by a warehouse and docks.[6] In 1836 Whitney sold the property to a group of businessmen from New York for $10,000.[7] Later Cadwallader C. Washburn and a business partner purchased the site.[4] In 1852 they replaced the finishing house and installed steam-operated equipment, nearly doubling the operation's productivity.[7] The shot tower was operated by a crew of six, producing between 600 and 800 pounds of quality shot per day. Miscast pieces were melted and reused. The finished shot, graded by size, was transported to Milwaukee and then shipped east.[3]

Operations ceased in 1860 during an economic downturn, and the buildings and equipment were sold away. The village of Helena was abandoned soon after. Thomas Shaunce died around 1860 as well. Throughout his life he experienced respiratory trouble from the air blast in the tunnel, and felt he had been cheated of his proper payment.[5]

Historians have noted that the Helena Shot Tower, which allowed a frontier resource to be shipped in a finished form, was significant in the settlement and prosperity of southwestern Wisconsin.[4][6] The overland teamster route developed to transport the operation's output to the east evolved into a road and then a rail line. Returning wagon teams brought supplies and immigrants.[7] Southwestern Wisconsin, once more closely tied to the Southern United States via the Mississippi River, built a population and culture closer to the northeast.[4]

Later history

In 1889 the site was purchased for $60 by the prominent Unitarian minister Jenkin Lloyd Jones, a member of a well-known Welsh-American family in the region. He created a recreational and educational retreat called the Tower Hill Pleasure Company, which provided outdoor recreation, visiting lecturers, books, and music. The retreat grew to include 25 cottages, as well as a dining pavilion, tennis courts, and other structures. One 1894 lecturer, a history professor, spent his free time excavating the shot tower's shaft and recovered several pieces of equipment which Lloyd Jones donated to the Wisconsin Historical Society.[4] In 1911 Jones' nephew Frank Lloyd Wright began building his studio Taliesin on a neighboring hill.

After Lloyd Jones died in 1918 his wife Edith donated the site to the state, and Tower Hill State Park was officially created in 1922. The smelting house and wooden shaft were rebuilt between 1970 and 1971 by the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources and the Wisconsin Historical Society.[8]

In 2006 parts of a horror film called Witches' Night were filmed within the state park.[9]

Recreation

Tower Hill State Park is open from May to October. Visitors can enter several historical structures. The smelting house contains exhibits about the construction and use of the shot tower. Structures remaining from the Tower Hill Pleasure Company include the pavilion (now the park's picnic shelter), a gazebo, and the foundation of a barn. There are two miles (3 km) of trails leading up to the tower and down to the riverbank, where visitors can enter the horizontal tunnel to the bottom of the shaft. There is a small campground with 15 campsites, drinking water, and pit toilets. Nearby attractions include Taliesin, the American Players Theatre, the House on the Rock, and Governor Dodge State Park.

References

- ^ "Shot Tower". Wisconsin Historical Society. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- ^ Anderson, Donald N. (July 24, 1972). "Shot Tower". NRHP Inventory-Nomination Form. National Park Service. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ^ a b "Tower Hill State Park Visitor". Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2006.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e Folkedahl, Beulah (Summer 1959). "Forgotten Villages: Helena". Wisconsin Magazine of History. 42 (4): 288–92.

- ^ a b c Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Tower Hill State Park interpretive signage.

- ^ a b Titus, W.A. (March 1928). "Historic Spots in Wisconsin: The Helena Shot-Tower". Wisconsin Magazine of History. 11 (3): 320–7.

- ^ a b c Stark, William F. (1988). Wisconsin, River of History.

- ^ Bogue, Margaret Beattie (1990). "Exploring Wisconsin's Waterways". Madison, Wis.: Legislative Reference Bureau.

- ^ Conklin, Melanie (May 14, 2000). "Movie crew films bewitching horror in Spring Green". Wisconsin State Journal. Madison, Wis. pp. 015.H.