Toruńska Street, Bydgoszcz

View of the street | |

Toruńska street highlighted on a map | |

| Native name | Ulica Toruńska w Bydgoszczy (Polish) |

|---|---|

| Former name(s) | Weg von Langenow, Thorner Chaussee, Thornerstraβe |

| Part of | Babia Wieś/Kapuściska/Zimne Wody/Lęgnowo districts |

| Namesake | Toruń |

| Owner | City of Bydgoszcz |

| Length | 11.2 km (7.0 mi) |

| Width | ca. 10m |

| Location | Bydgoszcz, |

| Construction | |

| Construction start | Middle Ages, end of 18th century[1] |

Toruńska Street is the longest and one of the most ancient streets in Bydgoszcz, Poland.[citation needed]

Location

The street runs west–east, from downtown Bernardyńskiego roundabout to the eastern border of the city with the village of Otorowo. It is 11.2 kilometres (7.0 mi) long.

From Bernardyńskiego roundabout to Toruńskiego roundabout, the street is used by the National road 80. To the east, the path runs through the following districts: Babia Wieś, Kapuściska, Zimne Wody and Łęgnowo.

History

Toruńska Street is an ancient route connecting Bydgoszcz and Toruń via Solec Kujawski: to get to Toruń downtown, it was then required to cross the Vistula river.

Early history

As early as in the Middle Ages, the path exited Bydgoszcz at the Kujawska Gate (Polish: Brama Kujawska) and was heading to "Toruń suburbs" (Polish: Toruńskie Przedmieście) or Kujawskie, just outside the city. Presumably this track was used until the 14th century, as part of Amber trade road: from Silesia to Pomerelia the road forded by ferry the Brda river at the village of Czersko Polskie, near the river's mouth to Vistula. This passage was controlled by the castellan of the "Wyszogród" stronghold (located in today's Fordon).

At the end of the 14th century-beginning of the 15th century, there was a clear intention to build a bridge in this place, according to written sources from Vladislaus II of Opole, the nobleman who granted Fordon city with town privileges in 1382. However, this project did not succeed: indeed, the ferry crossing had been operating there till the 19th century, ran by the owner of an inn called "Ujście".[2]

The oldest building in the vicinity of the street preserved to this day is the Bernardine Church of Our Lady Queen of Peace from 1557, standing today in Bernardyńska street. In 1783, the population of Przedmieście Toruńskie was 942.[3]

On the map of the vicinity of Bromberg from 1796 to 1802, the road to Solec Kujawski matches up with the present street.[1] On the other hand, on an 1857 map of the vicinity of the city, one can notice a few suburban buildings along the road, concentrated in farm-towns or folwarks:[4]

- Klein Bartelsee (Polish: Małe Bartodzieje);

- Kaltwasser (Polish: Zimne Wody);

- Gross Kapuscisko (Polish: Kapuściska Wielkie);

- Polieren Czersk (Polish: Czersko Polskie) or Olęders villages;

- Deutsch Czersk (Polish: Czersko Niemieckie);

- Langenau (Polish: Łęgnowo), founded in 1603;

- Otterowo (Polish: Otorowo), founded in 1604.

Until reaching Łęgnowo, the road ran in the vicinity of the Bydgoszcz hill.[4]

Prussian era

Initially, only the western section of the current street remained within the administrative boundaries of Bydgoszcz. With time and the growth of city area, fragments of the street were slowly included into Bydgoszcz territory:[5]

- in 1800, the suburban "Przedmieście Toruńskie", first village to the east;

- in 1851, a part of the area of called "Żup", where today stands the Łuczniczka hall;

- in 1920, after the re-creation of the Polish state, a dozen of eastern suburban communes were incorporated into the borders of Bydgoszcz, including Małe Bartodzieje, Kapuściska Wielkie, Zimne Wody and Czersko Polskie. Hence, in the interwar period, Toruńska Street ran within Bydgoszcz limits from the Old Town up to the rail crossing of the Warsaw-Bydgoszcz Railway put into use in 1861;

- in 1954, the timber port, located at the mouth of the Vistula;

- in 1977, "Łęgnowo II".

This final extension put the entire length of Toruńska street inside the administrative boundaries of Bydgoszcz.

In 1872, the street was connected to the newly laid Bernardyńska Street, in the area of the Zbożowy Rynek. Soon in the 1880s, industrial enterprises flourished in the swath of land wedged between the street and the Brda river, mainly wood-related business and sawmills: as such, they made up the first elements of an eastern warehouse and industrial district. At that time, the timber port in the village of Brdyujście operated a roller dam, the "Czersko Polskie Jaz" (English: weir), and a system of locks. Additionally, a dyke was built so as to cross the newly created reservoir.

On August 29, 1891, was established the "Bromberger Schleppschiffahrt Aktien Gesellschaft" (Polish: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Żeglugi Holowniczej Spółka Akcyjna) or "Bromberg Shipping Corporation". It built an industrial ensemble in Zimne Wody and excavated a shortening canal in a meander of the Brda river, creating today's "Zimne Wody Island", cut by the Sporna street built at the company's expense. The company still exists today as "OT Logistics S.A.".

In the first decades of the 20th century, the docks of the Brda river along Toruńska and Fordońska streets were teeming with several dozen of sawmills, carpentry shops and other timber factories using large quantities of wood coming from Russian Poland through the water route connecting Vistula and Brda rivers. The products were exported to the German Empire using the Bydgoszcz Canal and the Noteć, Warta and the Oder rivers.[6]

Interwar period

During the interwar, industrial urbanization further developed along Toruńska street.

Among the largest firms established in this period and still active, one can mention, among others:[7]

- "Fabryka Mebli O. i K. Pfefferkorna", today "Bydgoskie Fabryki Mebli S.A.";

- "Fabryka Wyrobów Gumowych „Kauczuk” Sp. Akc.", today "Stomil S.A.".

Other important companies are non-existent today, such as "Wielkopolska Huta Szkła", located at the crossing of Hutnicza and Toruńska streets on the site of

the 1892 former brick factory. From 1923 to 1948, it used to produce glass for bottles and windows.[8]

In the 1920s, several constructions were realized in the street along the Brda river:

- a water racing track;

- a passenger marina on the river;

- stands accommodating several thousands on "Wyspa w Brdyujście", the island at the mouth of the Vistula. The facility housed national and international events (e.g. 1929 European Rowing Championships, the annual All-Polish Regatta).

Furthermore, a bypass for the railroad coming from Bydgoszcz (part of the Polish Coal Trunk-Line) was put into service. It crossed the Brda River and the Toruńska street at the south of the "Wyspa w Brdyujście".

World War II and post-war years

During German occupation (1939-1945), the operations of Dynamit Nobel AG plant established in the southern Bydgoszcz forest of Łęgnowo required the construction of tens of kilometers of railway tracks, sidings and hundreds of kilometers of concrete-slab-paved roads, which all connected or crossed over Toruńska street. The activity even lead to the paving of a second path, parallel to the south to Toruńska street, named today Nowotoruńska street.[9]

After World War II, a new wave of building occurred along the street: companies, tram tracks and a tram depot as well as new housing estates in various districts (Wzgórze Wolności, Wyżyny, Kapuściska, Łuczniczki).

In 1969, started the construction project of the "W-Z" (English: East-West) route, devoted to improve road traffic in Bydgoszcz along the east–west axis. To that end were erected two rounadabout on the western portion of Toruńska street:

- "Rondo Toruńskie" at the intersection with Bernardyńska and Kujawska streets;

- "Rondo Bernardyńskie" at the crossing with the Pope John Paul II street which opened in the 1980s, as part of the National Road 80.[10]

In 1974, the "Park Centralny" was unveiled. It brought greenery on the area located between the Brda and the street.

After 1990, one can cite the following projects on Toruńska street:

- the construction of the Casimir III the Great bridge over the Brda, linking Toruńska and Fordońska streets (opened on November 30, 2000);[11]

- the construction of the Łuczniczka hall in 2002, followed by the erection of a smaller sports and entertainment arena, "Artego Arena" four years later;

- the renovation of the bridge along Sporna street in 2010;

- the "Kujawsko-Pomorska Szkoła Wyższa in Bydgoszcz" (English: Kujawsko-Pomorska High School) commissioned its seat at Nr.55 in 2008–2010;

- on May 17, 2010, the real estate "Osiedle Szeście Planet" was completed. It comprises a complex of 6 six-story buildings named after planets of the Solar System ("Mars", "Venus", "Jupiter", "Saturn", "Mercury" and "Neptune"). The complex was erected at Nos. 170–172, on the site of the former bakery "Tosta".

In December 2013, the "Trasa Uniwersytecka" (English: Road of the university) was commissioned, encompassing the construction of a tall road bridge over both the Brda and Toruńska street.[12]

From late 2019 to February 2021, the most western portion of the street has been closed to allow the reconstruction of the tram line in Kujawska street and the renovation of the sidewalks.[13] On February 5, 2021, the eastbound traffic was reopened.[14]

Future projects include:

- the renovation of the street combined with the paving of a bicycle path;[15]

- the renovation of tram tracks on the sections from "Rondo Toruński" to Spokojna street and from the tram depot to Spadzista street;[15]

- at Nr.28a, the "Adria estate" is planned, with two eight-story buildings;[16]

- in the plot at Nr.131 along the river, a new estate is planned, called "BRDA Smart City".[17]

Naming

During its existence, the street bore the following names:[3]

- from 1797, Weg von Langenow (English: Road from Langenau/Łęgnowo) or Weg von Thorn u. Schulitz

- 1820–1840, Thorner Chaussee

- 1840–1920, Thornerstraβe

- 1920–1939, Ulica Toruńska

- 1939–1945, Thornerstraβe

- from 1945, Ulica Toruńska

The thoroughfare has always been designated by the main city it leads to, i.e. Toruń: be it in German (Thorn) or in Polish (Toruńska). The successive extensions of the street, triggered by the enlargements of the city, required the updating of the house numbering for the buildings of the southern frontage, thanks to the use of the German "horseshoe numbering" system. For instance, the tenement at today's 14 was referenced at 183 Thornerstraβe in the 1910s and at 57 Thornerstraβe in the 19th century.[18]

Historical facts

The street is one of the main communication arteries and exit routes from Bydgoszcz, connecting downtown with the eastern suburbs on the southern side of the Brda river. 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) to the east, Toruńska runs along the picturesque dyke separating the water racing track stadium from the timber port.

Along the street in downtown, old tenement houses are still standing (some with Art Nouveau style) but they don't form a continuous frontage. More recent suburban buildings -generally real estate complexes- are present in the further eastern portions.

In the east of the Old Town, between the 12th and the 15th centuries, a salt mine had been operating. Later on, a ceramic industry developed here.

In the area of the former folwark of Bartodzieje Małe (at the present "Rondo Toruńskie") were erected in 1890, a folk school and an orphanage (at today's Bełzy street).

From 1910, a dozen of marinas were created along the right bank of the river Brda. Today, several rowing clubs are still active in the area, among which "Bydgoski Klub Wioślarek", "Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Wioślarskie" or "Bydgostia Bydgoszcz". This part of the city between Toruńska street and the Brda river is nicknamed the "Rowing district" (Polish: Dzielnica wioślarzy).

During interwar period, a housing estate was built in the parallel street of "Babia Wieś", along the Brda river. Its design was realized by architect Bogdan Raczkowski.[19]

Tram traffic

A tram line along Toruńska street was built in 1892: it was the second line of the city, horse-drawn, running from the barracks in Gdańska Street to the shooting range building ("Strzelnica ") at today's Nr.30.[20]

In 1896, electricity-powered engines replaced horse-drawn tractions. In 1953, a 26.2 kilometres (16.3 mi) long Brda-track was built, running along the right bank of the Brda river from Toruńska-Babia Wieś streets to the Chemical Complex "Zachem" in the south of Bydgoszcz, via Kapuściska and Łęgnowo districts.[21] Four new tram lines were using this new track: Nr.6, 7, 8 and 9, connecting the center with the eastern districts.[10] In 1959, a tram depot was unveiled at Nr.278; it was extended in 1978 with 11 branch lines.[20] In the 1960s, the network along Toruńska street was expanded by branches on Bernardyński Bridge (1963) and Pomorski Bridge (1970).

In February, 2019, two buildings in Toruńska street (nos.4 and 6) have been razed down[22] to allow the construction of the tram line along Kujawska Street.[23]

In September 2020, 3 derelict houses located at the fork between Toruńska and Bełzy streets were also demolished.[24]

In 2021, the following tram lines are using Toruńska street:[25]

- Nr.6, from "Rondo Bernardyńskie" to "Spadzista street";

- Nr.4, 7 and 8 from "Rondo Toruńskie" to "Perłowa street".

Main areas and edifices

Bernardine Church of Our Lady Queen of Peace, corner with Bernardyńska street

Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Heritage list Nr.601227, Reg.A/674 (March 4, 1931) and Nr.601228, Reg.A/674 (September 30, 1992)[26]

Mid-16th century

Polish Gothic architecture, Renaissance architecture

The origin of the church dates back to the arrival in 1480 of Bernardine monks in Bydgoszcz, coming from Kraków. In the years 1518–1524, the abbey was led by Bartholomew of Bydgoszcz, a scholar, author of the first Latin-Polish dictionary (1532, 1544). On September 23, 1552, king Sigismund II Augustus granted permission for the reconstruction of the burned Bernardine church., with a caveat to its height that should not be taller than the neighboring castle for military-defensive purposes. Its architecture reflects Gothic and Renaissance characteristics. After 1920, Polish authorities confirmed the use of the church for garrison purposes, as it is still used today. The church has been re-consecrated in 1923, by military bishop Stanisław Gall. In 1926, it was renamed Saint George military parish church.

- Main elevation with church tower in the backdrop

- Main portal

- Saint Anthony altar, now in Bydgoszcz cathedral

House at 11 - 4 Babia Wieś street

End of 19th century

This building displays a facade on Toruńska Street and a backyard on Babia Wieś street.

- View from Toruńska street

- Backyard onto Babia Wieś street

Tenement at 12

1895[27]

The building was constructed as an hotel, commissioned by Emil Röpcke (or Roepkes),[18] living at 1 Dorotheenstraße (today's Ustronie street). The institution was then run by Hugo Sauer till the end of World War II, under the name "Roepkes Hotel".[28]

With the razing in 2019 of the edifices closer to the roundabout, this building is now the first standing on the even side of the street: following the angling path of the road, it presents a two-face frontage. Apart from the bossage ornamenting the facade ground floor, one can highlight the original bay window incorporating wooden elements and stucco details. The first frontage also displays nicely decorated mullions on its openings.

- The building as an hotel ca 1913

- Main frontage in the late 2010s

Tenement at 14

1880s [27]

The first reference to the building dates back to 1880, as the property of J.F. Semerau, owner of a copper ware factory and living at 5 Kirchenstraße (today's Madzińskiego street).[29] At the turn of the 20th century[18] till the 1910s,[30] the new landlord was Paul Bresgott, an architect.

The tenement displays a traditional eclectic facade. One can notice the portal flanked with lesenes, which lintel bears the word SALVE as well as two putto angels.

- Main frontage

- Detail of the lintel

Tenement at 15 - 6 Babia Wieś street

1890s[31]

The first registered landlord of the building at then "6 Toruńska" and previously "6 Thornerstraβe" was Carl Bennewitz, a wheel craftsman producing wagons.[32] The ensemble has an elevation onto Toruńska Street (Nr.15) and the courtyard housing the ancient brick workshop onto Babia Wieś street.

- View of the courtyard from the Babia Wieś street

Tenement at 16

ca 1910[27]

Although older buildings were previously identified here, the current tenement was commissioned by a merchand, Robert Scheurich.[30] In the addressbook of 1911, it was registered at 56 Thörnerstraße.

The interesting elements of the facade are located in the triangular bay window, topped by a round wrought iron balcony.

- Elevation on the street

Tenement at 18

ca 1910[27]

The actual tenement had for first landlord Carl Quandt, carpenter and owner of a piano workshop located in the suburban village of "Schwedenhöhe" (present day Szwederowo district).[30]

- Elevation on the street

Theater "Adria" at 30

1867,[27] by Eduard Titz, Heinrich Gelzer

The facility was built by Bydgoszcz "Fowler Brotherhood" (Polish: Bydgoskie Bractwo Kurkowe), an organization with 15th-century traditions. The "Fowler Brotherhood" was a fraternity initially training citizens to protect the city walls. Since in those days the most important skill was considered to be archery, men were practising trying to aim at a fowl, hence the fowler naming.[33] In Bydgoszcz, the association had from the 17th century its own shooting range located in Przedmieście Toruńskie and kept on purchasing plots in the vicinity. In 1866, the Brotherhood decided to build a new building on this plot where it had one of its earliest shooting ranges established. It comprised a social house, a new shooting range and a banquet hall with extensive facilities. There was a spacious garden adjacent to the building, with a summer theater. The ensemble was planned as multi-functional, housing the meetings of various associations, assemblies, elections to the national parliament, as well as theater performances and concerts.[34]

The cornerstone was laid on May 23, 1866, during a ceremony attended by the Fowler Brotherhood, Johann Naumann (the president of the region), the construction counselor as well as members of the magistrate and city councilors. Construction completion was delayed for several months due to the outbreak of the Austro-Prussian War. On June 6, 1867, the facility was officially open.

The building was part of a large entertainment complex, situated in a 10-morgen garden at the foot of the hill. Behind the building was a garden with six stagged terraces, shaded by trees. The open veranda could accommodate a 50-musicians orchestra. Naturally, the garden housed a summer shooting range equipped with modern devices. With time, the facility was gradually enriched with new pavilions and separate entertainment areas:

- in 1868, a 300 square metres (0.074 acres) circus with an amphitheater was added to the south;

- in the garden were erected a buffet, a beer garden, an orangery, a playground and an observation deck;

- in 1891, an outdoor bowling alley was constructed along the eastern border of the property.

At the end of the 19th century, the place was very popular among Bromberg residents. Prominent artists performed on the stage: Hans von Bülow (1880), Eugen d'Albert and Teresa Carreno (1891) or the Meiningen orchestra under the direction of Max Reger (1912).[35] Numerous concerts, performances, celebrations, lectures and scientific shows took place here, including the yearly shooting festivals.

On the night of October 13, 1900, the complex of the Brotherhood burned down completely. In 1903, the design of the new building was proposed, probably by the architect Heinrich Gelzer. The new shooting range was slightly different in design from the previous one.

Until 1938, the facility still belonged to the Bydgoszcz Fowler Brotherhood and then moved into the hands of the "Sokół" Gymnastic Society. Under Polish authority, the complex played the same cultural role as during the Prussian period, with orchestra and musical group performances and association gatherings. One of the banquet was attended by General Józef Haller. Children could enjoy puppet theater shows. Every day, free games for children and adults took place in the garden and on Sundays and holidays, popular music with dances were common.[35]

At the end of World War II, the place did not resume its activities. In 1955, the institution was nationalized and it first housed the Provincial Cultural Center (Polish: Kujawsko-Pomorskie Centrum Kultury) and then a movie theater, "Adria". In addition to film screenings, "Adria" also welcomed theater plays, concerts or meetings. As far as the garden is concerned, its maintenance was simply abandoned. "Adria" kept a movie activity till 2002, vanquished by the new generation of Multiplex. The place maintained a cultural activity after this date.

In 2018, a small residential complex called "Adria" was designed on the back plots where used to be located the shooting ranges;[36] it was put into use at the end of 2020.[37]

The "Adria" facility houses in 2021 a traditional single-screen movie theater accommodating 400 customers. There is also a professional theater and performance stage with back-up facilities. Regularly are scheduled classical and light music concerts, cabaret, dance or theater performances, election meetings, company events and various shows.[38]

The first edifice was designed by Berlin architect Eduard Titz, known at the time for his theater realisations in Berlin, Görlitz and Zittau. The inside paintings were designed by the architect Martin Gropius. The frontage along Toruńska street was about 60 metres (200 ft) long. The façade displayed a neoclassic style, with a main central body, flanked by small wings. The entrance to the building lead to a vestibule, from where you could reach the main room, so-called "Royal Hall". It was the largest room (32 metres (105 ft) long, 18.8 metres (62 ft) wide, 8 metres (26 ft) high) and decorated with paintings, curtains, mythology figures and busts of royal family members and playwrights (Goethe and Schiller). The rooms were lit by gilded gas lamp chandeliers. The theater was constructed in such a way that it could be used both from the hall and from the garden as a summer theater. The ground floor also housed a dining room, a social room, a billiard room and an indoor shooting range. There were additionally smaller rooms and two apartments on the first floor.

The rebuilt edifice differed from its predecessor in that the main hall stretched outward and ended with the stage, which made it easier to achieve good acoustics conditions. It could house 462 spectators during the performances. On the right side there was a dining room, a buffet and kitchens. On the first floor, above the dining room, were located guest rooms. The outside frontage on the street, however kept its general shape with a central body and two side wings. Similarly, the neo-classical decor of elevation was preserved. The furniture of the rebuilt complex was updated with electrical installation and central heating.

- The edifice on a 1900 postcard

- Main elevation

- View from the street

Villa at 37, corner with Babia Wieś street

ca 1897

Dated from 1897, as mentioned on the facade pediment, the villa was owned by a butcher, Richard Fröhlich.[39] At the time, its address was 12 Thörnerstraße.

Renovated in 2021, the villa displays many architectural motifs, in particular a window above the entrance adorned with columns bearing lion's heads, a triangular gable and two urns standing at each extremity of the elevation.

- View from the street

- The villa after renovation

Tenement at 38

1895[27]

The current building had for first landlord Caroline Raszewski née ßrill, the widow of a police sergeant.[18]

- View from the street

Vocational woodworking school at 44

On the plot of the vocational school for wood (Polish: Zespół Szkół Drzewnych w Bydgoszczy) stood in the late 19th century the "Samuel Zimmer machine Factory" (Polish: Fabryka Maszyn Samuela Zimmera).[40] Set up in 1884 by engineer Zimmer within the Blumwe's factory premises at Wilhelmestraße (today's Nakielska street), the company moved in October 1898, into the newly built factory at this very spot. It then employed 30 workers and was specialized in producing straw elevators for threshing machines.[40]

- View of the Zimmer Factory ca 1900s

- Advertising for the Zimmer machine Factory ca 1900s

Real estate complex "Arkada Park" at 45

End 19th century[27]

In this plot used to stand the laundry for the Bromberg garrison (German: Garnison waschanstalt), built in 1888–1889.[41]

In the late 2000s, the buildings were transformed into a loft ensemble called "Arkada Park". Few old brick garrison buildings have been preserved and integrated into the complex:[42]

- the ancient administrative building still stands directly onto the street. It used to host inspectors of the military garrison and housed during the interwar period, among others, the military tax office or the Bydgoszcz garrison Directorate;

- embedded into the estate apartments is the ancient laundry itself.

- Ancient seat of the military administration

- Ancient garrison laundry

Building at 46

End 19th century[27]

The large villa has been commissioned by Julius Esser, a rentier.[18] In the first years of the 20th century, after a landlordship change, it housed several deaconesses.[39] The address of the place switched many times since its inception: initially "44 Thörnerstraße", then 54 (1910s), 167 (1920s) and finally 46 Toruńska street.

Although in need of repair, the house still displays a wrought iron balcony above the main entrance, topped by an oeil-de-boeuf inserted in the wall gable.

- View from the street

Building at 49

Late 1920s[27]

These tenements have been commissioned by the city authorities (Polish: Magistrat Bydgoszczy). In 2017, as part of the visual street festival "Bite Art", a mural by artists Adam Kłodziński and Sebastian Tkaczyk has been realized on a wall of the building, named "Panienka z okienka" ("Young lady at the window").[43]

Erected in the late 1920s, the edifice reflects the modernist style of its time.

- The building ca 1928

- Current view from the street

- Mural "Panienka z okienka"

Building at 50

Late 19th century[27]

The house belonged to Ernst Emil Peterson, the mayor of Bromberg from 1840 to 1844.[44] It then moved into the hands of his son Carl Julius Peterson, also mayor from 1881 to 1889. At the turn of the 20th century, the grand edifice was owned by the "Fowler Brotherhood" (German: Schützengilde).[28] In the 1920s, Antoni Weynerowski purchased the edifice. He was a Polish entrepreneur, founder in Bydgoszcz of the firm Leo, renamed Kobra, one of the largest in Poland in the interwar period. After the end of World War II, the building housed a private post-secondary school, "FAMA". In the 2010s, the tenement has been left empty.

- View from the street

- Main frontage on the street

Building at 61

Late 19th century[27]

The first registered landlord in 1880 was Mr Remiß, a shipbuilder, who did not live there.[29] At the time, the tenement was located at 27 Thörnerstraße, at the border of Bromberg territory.

- Frontage on the street

Park Centralny

Park Centralny (English: Central Park) is an urban green area located along the side of the Brda river in Bydgoszcz, Poland. The park covers 6.22 hectares (15.4 acres).

- View along the Brda

- View of an alley

Building at 66

Late 19th century[27]

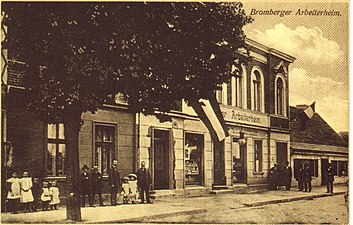

Friedrich Galow, listed as innkeeper, was the first owner of this building.[29] In 1910, the edifice housed the "Bromberger Arbeiterheim" (English: Bydgoszcz Worker's House). This association was founded in October 1906, with the aim of "building nationalist awareness among the German working class". It was harbouring meetings for representatives of various professions.

The facade still displays the faded mention of this activity. After World War I, the city authorities took over the house. A grocery store operated there afterwards: its faded labels are also visible on the elevation.

- The "Bromberger Arbeiterheim" ca 1900

- Facade with faded writings in German and Polish

Park na Wzgórzu Wolności

Park na Wzgórzu Wolności (English: Park on Freedom Hill) is a city green area covering almost 10 hectares (25 acres), located on the heights of the city, on the southern side of the street. Within the park is located the "Cemetery of Bydgoszcz Heroes" (Polish: Cmentarz Bohaterów Bydgoszczy). Established in 1946 on a plot of 0.66 hectares (1.6 acres)[45] where used to stand the city Bismarck tower,[46] the graveyard houses 1169 inhabitants of Bydgoszcz, murdered during the Nazi occupation of the city. It includes the victimes executed at the Old Market square, at the Valley of Death and in the surrounding forests. The corpses have been exhumed from 1946 to 1948 and solemnly buried there.[45]

- View of an alley

- In autumn

- Entrance to the cemetery

- Graveyard

Friedrich Rellier tenement at 70

End of 19th century[27]

Friedrich Rellier was a logging entrepreneur.[47] The Rellier family had ownership of this building from the 1880s till the outbreak of World War II.[48]

The elevation displays classical eclectic style.

- Facade on the street

Tenement at 72

ca 1900[27]

Eclecticism, early Art Nouveau

Built at the turn of the 20th century, the building changed regularly its address: initially at 29 Thörnerstraße, it bore in turn the numbers 29/29a, 29a and 154 before the current 72 Toruńska street. Its first landlords were Wilhelm Devantier and Wilhelm Kirsch.[18]

The frontage kept its round wall gable as well as a half-moon window as reminder of its now gone Art Nouveau decoration.

- Facade on the street

Tenement at 80

1900s[27]

Paul Krüger, a leather tailor, was the owner of this building at its inception in 1901.[49]

The derelict frontage only kept the cartouches of the first floor lintels.

- Facade on the street

Tenement at 82

1900s[27]

Referenced at 27c Thörnerstraße at its erection, the tenement had for first landlord master mason Emil Heidemann,[50] also owner of houses at 804and 86. One can guess he had been interested in its construction, if not involved.

Some remnants of the decoration are to be found on the designed corbels supporting the lower right facade. One can still notice the figure head in a medalion encompassed in the pediment above the street entrance.

- View from the street

Tenement at 84

1910[27]

The building at then 27b Thörnerstraße was the property of master mason Emil Heidemann,[50] also owner of houses at 82 and 86.

In contrast with the frontages at 80 and 82, this elevation displays preserved Art Nouveau motifs: from the curved shape of the wooden double door with its transom to the convoluted design of the wrought iron balconies to the faded but still visible floral motifs on top of the facade. One of the roof dormers is topped by a pinnacle.

- Main elevation

Emil Heidemann tenement at 86

1905[27]

Emil Heidemann, the master mason who owned the houses at 82 and 84, was living in this abode, then at 27a Thörnerstraße.[51]

In September 2016, a mural was unveiled on the side wall of the house.[52] The painting was part of the project organized on the occasion of the city's 670th birthday, "Legends of Bydgoszcz" and refers to the history of the city and its related parables.[53]

The offset elevation on the street displays many Art Nouveau details, such as a woman figure at the base of the terrace, adorned cartouches and decorated pediments.

- Main elevation

- Mural at 86 Toruńska Street

Klein Bartelsee houses

From 1880s to 1910s[27]

Many houses on the ancient territory of the "Klein Bartelsee" suburban village (today's Polish: Małe Bartodzieje) present the same structure, with a main eclectic facade on the street and one storey. Some of them were initially used as inns.

| Location (Building date)[27] | Picture | First owner | Remarks |

| N.67 (1910) |  |

Amandus Zeiß, a ship-owner.[30] | Early modernism. The facade still displays a nice wrought iron balcony. |

| N.69 (1910) |  |

Adolf Bukowski, an entrepreneur in stone business.[28] | Early modernism. Then at 65 Chausseestraße, in "Klein Bartelsee" (today's Bartodzieje Małe district).[30] |

| N.92 (1903) |  |

Josef Böhnisch | The elevation still bears the date of its erection, i.e. 1903. |

| N.102 (1880s)[54] |  |

Johan Tartowski | In 1910, the house moved in the hands of the Bernhardt family till World War II.[30] |

| N.106 (1880s) |  |

Johan Zemisch | Some bossage elements are still present at the wall angles. |

| N.123 (1890s) |  |

Emil Böhlke. | The house was initially an inn.[18] Its elevation still bears the date of its erection, i.e. 1903. |

| N.132 (1890s) |  |

Eduard Samulewicz | The house was initially an inn.[41] |

| N.138 (1914) |  |

Adolf Kloßbücher. | The house was initially an inn.[28] It still bears the date of its erection (1914) together with cartouches and rosettes. |

| N.142 (1880s) |  |

August Werdien (Werdin), a blacksmith.[29] | One of the oldest house in the street. |

Tenement at 110

1890s[27]

Otto John was registered as the first owner of this house at then 19 Klein Bartelsee.[41]

The deteriorated facade still displays some motifs around the windows.

- View of the elevation on the street

Villa Jekiel at 112

1920s[27]

The commissioner of this villa was Stanisław Jekiel, a bookshop owner.[55] At the time, the other tenants were a painter, Stanisław Kandzia and Adela Kandzia, a tailor.[55]

- View from the street

"STOMIL", Rubber manufacturing Joint-stock company at 155

1920[56]

Bydgoska Spółka Akcyjna "Kauczuk" was established with a capital of Mp.100 million in 1920 in Bydgoszcz, with its main seat in Warsaw.[57] At that time, only one factory in Poland was producing rubber products since 1911 in Wolbrom.[58] Soon (1918-1923), other Polish rubber factories would be set up ("Brage" in Warsaw or "PePeGe" in Grudziądz).[58] The Bydgoszcz factory started to be erected in 1921, on a 23 hectares (57 acres) plot of the commune of Zimne Wody left bare after a fire destroyed the sawmill that used to stand there. The most modern machine tools for rubber processing and fabrics gumming were imported from England.[59] Production started in the middle of 1923 and a year later the factory reached its the full capacity, employing 200 people. In 1928, the workforce reached 500.[58]

First products were initially insulating tapes, rubber and asbestos discs, coated fabrics, ebonite, molded articlesa nd inner tubes for bicycle tyres. The plant was one of the five largest in Poland and the most important chemical industry company in the city.[60] Products were sold, among others, in the Free City of Danzig successfully competing with German goods. During the Great Depression, the company initially prospered, but in 1934, the economic situation deteriorated so much that production had to stop for three years.[60] In 1937, the plant was leased and renamed Spółka Dzierżawna Fabryka Wyrobów Gumowych "Kauczuk" (English: Leasing Company Rubber Products Factory "Kauczuk) with new shareholders.[58]

In 1939, Germans took over the factory, renaming it "Gumiwarenfabrik - Kautschuk": in addition to rubber, a metal department was launched, producing for the Wehrmacht field kitchens, parts for cannons, chassis, guns and also submarine outboard motors at the end of the war.[61] The number of employees quickly raised from 150 in September 1939 to 1,000 in 1944 (including 600 Soviet POWs).[58]

On April 4, 1945, the company was taken over by the Polish administration. The Soviet military authorities planned to move the facility to Soviet Union.[62] The movement was prevented after the intervention of the Polish authorities at the Economic Mission of the USSR in Warsaw in May 1945. In 1946, the factory was nationalized and in 1947, the name was changed to "Wytwórnia nr 10 Kauczuk" (English: Plant N.10 Caoutchouc). A year later the firm employed 483 people[62] and in 1950 it was renamed anew Bydgoskie Zakłady Przemysłu Gumowego "Kauczuk", reaching a workforce of 2500 people in 1970.[63] In 1960, a new hall was put into operation which produced in particular mining conveyor belts.[58] Since October 6, 1971, the Bydgoskie Zakłady Przemysłu Gumowego "Stomil" had branches in Podgórzyn near Zielona Góra and in Łabiszyn. Production was exported, inter alia, to Canada, West Germany, France, Netherlands, Finland, Greece, Austria, Soviet Union and Cuba.[58] In 1976, the company was forced, under pressure from the central administration, to replace foreign rubber by low-quality Polish artificial material.[64] In the second half of the 1970s, the company had regularly to halt production for lack of raw material (e.g. brass).[64]

In the 1990s, "Stomil" revised its production: of hydraulic hoses in Bydgoszcz, profile seals in Łabiszyn and mining equipment in Podgórzyn.[59] The company passed through the economic transformation without layoffs, maintaining financial liquidity. It also realized an association with the Medical School in Bydgoszcz, allowing students to spent time "Stomil" resting centers of in Dźwirzyno, Karpacz, Tuszyn.[59] On June 8, 1998, the company was transformed into a Joint-stock company.[58]

At the turn of the 20th and 21st centuries, the company tried to adapt to the new market conditions, undergoing a deep organizational and property restructuring. The amount of employment was gradually adjusted to the current production needs and the assets which were not directly related to production, but constituted an additional financial burden for the plant, were reduced.

From 2010 to 2018, the company kept on developing and improving its products. On October 2, 2018, BZPG "Stomil" S.A. changed hands, becoming the property of the capital group Agencja Rozwoju Przemysłu.

- Administration building

- Production plant viewed from the Brda river

Roller dam at 157

1906

The first works on Bromberg sewage system along the Brda river were carried out in 1877–1879. During this period, a lock was erected in the village of Brdyujście and two needle dams at Czersko Polski. During a modernization of the water junctions in 1904–1907, the Brdyujście lock was reinforced to stand the intensifying flow which resulted from the razing of an upstream lock at Kapuściska. From the original dam, only granite abutments survived, most of the time underwater.[65] Additionally, a power plant on the left side of the dam was built. The cost of these works was at the time 1.2 million marks, two-third of which were financed by the municipal budget.[65]

The rationale for the modernization of the dike was the need to expand the city "Timber Port", following the increasing wood transport traffic from Congress Poland and Małopolska towards German Empire using the Vistula-Oder waterways. Hence, after the completion of the weir in 1906, 5 million m³ of wood was ferried the Brdyujście dam, accounting for one-third of all German wood importations.[66]

Between 1994 and 1997, the dam was extended with a three-span, reinforced concrete, side overflow, where a second hydroelectric power plant was set up by the company "Mewat", today's "TRMEW".[67] In 2005, the old dam was renovated so as to restore the operational capacity of the hoisting mechanisms.[68] It is the oldest cylindrical weir in Poland.

- View from the street

- View of the side house

- Detail of the dam

Saint Joseph cemetery, at 162

1862, covering 1.3 hectares (3.2 acres)

Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship Heritage List (Nr.601246, A/1088), 24 November 1993[69]

The cemetery was established in 1822 for the needs of the Evangelical Church parish in "Kleine Bartelsee" ("Bartodzieje Małe")[70] and was open to both Evangelicals and Catholics. Between 1903 and 1906 the current Saint Joseph church was built beside. At the end of World War II, the Evangelical parish ceased to exist and the city authorities handed over the church to the catholic community: the building was consecrated on October 1, 1946, as "Kościół św. Józefa Rzemieślnika" (English: Church St. Joseph the worker) and the management of the cemetery was handed over to the municipal services.[70]

In the 1940s, a plot for the fallen Polish soldiers and residents of Bydgoszcz during World War II was established. It houses the mass graves of 69 people. The area is separated from the rest of the cemetery by a hedge. A concrete monument in the shape of stylized bas-relief eagle stands on a pedestal.[71]

- Old Chapel to St. Joseph

- Statue of Jesus Christ from 1929

- Monument in the military plot

Saint Joseph Church, at 166

1906

Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship Heritage List (Nr.601236, A/852), 30 January 1996[69]

The Evangelical community, established in 1901 in the village of "Kleine Bartelsee", consisted almost exclusively of Germans. The construction of the church was part of a greater movement of development of the Evangelical parishes in Bromberg and its suburbs at the eve of the 20th century. Hence while the current church was being built, several suburbans villages were also carrying out the same Neo-Gothic brick projects: Wilczak (Church of Divine Mercy in Nakielska Street), Okole, Czyżkówko and Szwederowo (now-past Evangelical Church of Martin Luther). William Faure became the pastor of the parish from its beginnings in 1906 till 1930. The temple served the German Evangelical community until 1945, although the congregation did not flourish past the outbreak of World War I.

After World War II, the Evangelical parish ceased to be used and the city authorities handed it over to the Catholics. The newly consecrated church was named after Joseph of Nazareth: it was initially used as the rector's church and a filial church of Bydgoszcz Cathedral. The independent parish was eventually established on October 1, 1946. In the 1960s and 1970s, the church provided pastoral services for the growing number of inhabitants living in the newly built housing estates of Wyżyn and Kapuściska districts. On October 15, 2006, bishop Jan Tyrawa solemny consecrated the church. In 2019, the city authorities funded the renovation of the facade which began in the second half of the same year.[72]

The design of the temple is the work of Ismar Hermann, a "royal district building inspector", in 1904. The scheme had been approved in Berlin by Oskar Hoßfeld at the Ministry of Public Works, which had been supervising all religious constructions in the territory under Prussian rule. The same Oskar Hoßfeld devised in the early 1910s the Church of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in Bydgoszcz.

The church displays eclectic style, combining Neo-Gothic and Neo-Romanesque features.[73] The frontage is dominated by a massive bell tower topped with a baroque ridge turret. The church has a single nave, with a straight chancel facing south. In the south-west corner is located the sacristy. The triangular gable annexes and the tower are decorated with plastered panels. The Neo-Gothic style of the building is mainly highlighted by the outside buttress blocks, the interior rib vault, windows with tracery and a gable topping the main portal.

- View from the street

- Side view

- Detail of the turret

- Interiors during a service

Buildings at 262

1935[27]

In mid-1930s, a building committee to erect there a church was established, at the initiative of Bydgoszcz parish priest Józef Schulz (1884-1940). Already in early 1938, masses were celebrated in the nearby primary school N.7. Thanks to the dedication of the local population and entrepreneurs, construction works started at the end of 1938.[74] The first construction was a presbytery, followed by the church nave and its belfry. Unfortunately, the outbreak of World War II shattered the entire project of the parish creation. Having seized the buildings, the German forces reconverted them to produce acetylene. After 1945, the chemical plant kept operating, manufacturing as well other industrial gases.[74] Once decommissioned, the ensemble was taken over by the company "Bydgoska FAbryka NArzędzi" (English: Bydgoszcz Factory of Files and Tools), or BEFANA, which seat was at 13 Obrońców Bydgoszczy street.[75] Afterwards, the plot has been privately owned: it is now the occupied by the tyre firm "Unigum".

Today are still visible on the site the rectory building and the brick church and the belfry.

- View of the ancient church

Building at 400

World War II period[27]

Built during the second world war by German forces, this tower housed a water coagulation facility. Its role was to filter and treat the water of the close Bromberg Dynamit Nobel AG Factory of Łęgnowo. The process was especially efficient in removing the chemical phosphorus from water.[76]

- Current view from the street

Mennonite house at 406

1768[27]

Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship Heritage List (Nr.601460, 54/A), 23 October 1970[69]

The house is located in the ancient village of Łęgnowo, now a district of Bydgoszcz. Łęgnowo was founded in 1603 by Olęders. This building is a remnant of this time, built in 1768 for the Mennonite community established in the neighbouring village of Otorowo. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the inhabitants of this area were mostly German settlers of the Evangelical faith. The edifice has been renovated in 2014–2015.[77]

- Front view

- Side barns

Church of Our Lady Queen of Poland, at 428

1910-1911

Registered on Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship Heritage List (Nr.A/1746), 13 September 2019[69]

The erection of this church, like Saint Joseph Church at Nr.166, was part of the scheme of expansion of the evangelical communities of Bromberg and its vicinity at the end of the 19th century. An Evangelical parish was established in the area of Łęgnowo before 1885 and at the beginning of the 20th century, the community obtained the permission to build its own temple. The construction and furnishing works covered 1910 and 1911.[78] At the same time, an Evangelical cemetery was set up in the centre of the village.

The temple served the community until 1945, although the onset of World War I put an end to the increase of the population. After the end of World War II, the church was handed over to the Catholic parish of Stanislaus of Szczepanów in Solec Kujawski: it was consecrated on September 9, 1945, by Father Franciszek Hanelt and served from 1945 to 1958 as a branch of the parish in Solec Kujawski.

On July 1, 1958, a pastoral centre was established in Łęgnowo-Plątnów and the church was therefore used by the local community. The parish of Our Lady Queen of Poland was officially created on May 31, 1968, by Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński.[78] In 1974, a presbytery was built on the location of the demolished pastor's house and the original farm building was converted into a catechetical house. Today, it houses the local branch of the Caritas association. In 1978, with the extension of Bydgoszcz territory, the church became part of the diocese of Bydgoszcz.

The church was built in the neo-Gothic style, very popular in Bromberg at the beginning of the 20th century, especially for religious buildings.[73] Bricks are the main construction element, used together with plaster. It has a single nave, with a square, closed chancel facing east and possesses a tower. The latter is five-story high, topped with a tented roof and dormers. The west side of the church is decorated with pinnacles. Inside, a wooden upper gallery has been preserved. The nave displays wooden barrel vaults and the chancel cross vaults.

- View from the street

- Church tower

- Church door

See also

References

- ^ a b von Schroetter (1796). Karte von Ost-Preussen nebst Preussisch Litthauen und West-Preussen nebst dem Netzdistrict aufgenommen unter Leitung des Preuss [Map of East Prussia together with Preussisch Litthauen and West Prussia together with the Netzdistrict] (Map) (in German). Staats Minister.

- ^ Łbik, Lech (1998). Średniowieczne brody i przeprawy na dolnej Brdzie w okolicy Bydgoszczy. Kronika Bydgoska XIX. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 131–145.

- ^ a b Czachorowski, Antoni (1997). Atlas historyczny miast polskich. Tom II Kujawy. Zeszyt I Bydgoszcz. Toruń: Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika. pp. 32–50.

- ^ a b von Schulz (1857). Plan von Bromberg und Umgegen zwischen der Weichsel und Netze sowie dern Königl. Oberförstereien Wtelno u. Glinke [Plan of Bromberg and the surrounding area between the Vistula and Netze as well as the Königl. Wtelno and Glinke chief foresters] (Map). 1:25000 (in German). Berlin: Metallographirt von C. Brügner.

- ^ Licznerski, Alfons (1965). Rozwój terytorialny Bydgoszczy. Kronika Bydgoska II. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 7–16.

- ^ Sławińska, Krystyna (1969). Przemysł drzewny w Bydgoszczy i w okolicy w latach 1871–1914: Prace Komisji Historii t.VI Prace Wydziału Nauk Humanistycznych. Seria C. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe.

- ^ Żłobińska, Łucja (1995). Bydgoski "Kauczuk" – "Stomil". Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 98–101.

- ^ Siwiak, Wojciech (2003). Wielkopolska Huta Szkła z Czerska Polskiego (lata 1923–1948). Kronika Bydgoska XXIV. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 315–346.

- ^ Pszczółkowski Michał, Czechowski Maciej (2011). Eksploseum DAG Fabrik Bromberg wybuchowa historia Bydgoszczy – informator. Bydgoszcz: Muzeum Okręgowe im. Leona Wyczółkowskiego w Bydgoszczy.

- ^ a b Michalski, Stanisław (1988). Bydgoszcz wczoraj i dziś. Warsaw-Poznań: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe. ISBN 8301054654.

- ^ "Nowe Mosty Nad Brdą - dla tramwajów, samochodów, rowerów i pieszych". zdmikp.bydgoszcz.pl. ZDMIKP. 21 August 2020. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "12 grudnia otwarcie trasy Uniwersyteckiej! Uroczystości mają być skromne". expressbydgoski.pl. Polska Press Sp. z o. o. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Ulica Toruńska zyskuje na przebudowie ulicy Kujawskiejdate=4 February 2020". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Tyczyno, Andrzej (28 December 2020). "Na otwarcie ul. Toruńskiej bydgoscy kierowcy muszą jeszcze poczekać". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ a b Leszczyńska, Marta (3 April 2016). "Toruńską po nowych torach i na rowerze. Ambitne plany". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ "Osiedle Adria jednak powstanie. Dwa wieżowce przy Toruńskiej". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. 2 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ Leszczyńska, Marta (20 September 2017). "Osiedle sterowane komórką powstanie nad Brdą". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 18 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1895 auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1895. pp. 17, 21, 31, 38, 58, 65, 135, 141.

- ^ Wysocka, Agnieska (2004). Bogdan Raczkowski-architekt i urbanista międzywojennej Bydgoszczy. Kronika Bydgoska XXVI. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 466–485.

- ^ a b Rasmus, Hugo (1996). Od tramwaju konnego do elektrycznego. Kronika Bydgoska XVII. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 185–188.

- ^ Dębicki, Witold (1996). Komunikacja miejska. Bydgoska gospodarka komunalna. Bydgoszcz: Instytut Wydawniczy "Świadectwo". ISBN 8385860371.

- ^ ml, Roman Bosiacki (20 February 2019). "Drugi dzień wyburzeń przy rondzie. Buldożery zmiatają domy". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ dss, Roman Bosiacki (8 February 2019). "Ostatnia taka Kujawska i Toruńska. Początek rozbiórek pod nową trasę z tramwajem". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Zniknęły rudery nieopodal ronda Toruńskiego w Bydgoszczy". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. 20 September 2020. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ "Schemat topograficzny linii tramwajowych i autobusowych" (PDF). zdmikp.bydgoszcz.pl. ZDMIKP. 5 June 2021. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Załącznik do uchwały Nr XXXIV/601/13 Sejmiku Województwa Kujawsko-Pomorskiego z dnia 20 maja 2013 r.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Gmina Ewidencja Zabytków Miasta Bydgoszczy Zarządzenie 439/2015. Bydgoszcz: Miasta Bydgoszczy. 7 August 2015. pp. 79–82.

- ^ a b c d Adressbuch nebst Allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg mit Vororten für das Jahr 1915 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1915. pp. 144, 161, 246, 336, 442.

- ^ a b c d Wohnungs-Anzeiger nebst Adress- und Geschäfts-Handbuch für Bromberg und Umgebung : auf das Jahr 1880. Bromberg: Mittlersche Buchhandlung (A. Fromm Nachf.). 1880. pp. 39, 114, 130, XXXXV.

- ^ a b c d e f Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten für das Jahr 1911 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1911. pp. 171, 239, 431, 454, 522.

- ^ Zarządzen NR 439/2015 Prezydenta Miasta Bydgoszczy ie Uchwala NR XLI/875/13. Bydgoszcz: Miasta Bydgoszczy. 7 August 2015. p. 40.

- ^ Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1890 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Dittmann. 1890. p. 59.

- ^ "The Fowler Brotherhood". Krakow wiki. 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Bręczewska-Kulesza, Dariadate=2008. Dom towarzyski Bractwa Kurkowego w Bydgoszczy. Materiały do dziejów kultury i sztuki Bydgoszczy i regionu. zeszyt 13. Bydgoszcz: Pracownia Dokumentacji i Popularyzacji Zabytków Wojewódzkiego Ośrodka Kultury w Bydgoszczy.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Pruss Zdzisław, Weber Alicja, Kuczma Rajmund (2004). Bydgoski leksykon muzyczny. Bydgoszcz: Kujawsko-Pomorskie Towarzystwo Kulturalne. p. 407.

- ^ Czajkowska, Małgorzata (27 August 2019). "Spór o cień. Sprawą dwóch bloków w Bydgoszczy zajmie się NSA". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ Czajkowska, Małgorzata (9 November 2020). "Inwestycja w centrum Bydgoszczy zakończona. A w sądzie trwa batalia o słońce". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ "Adria Teatr". kinoadria.pl. kinoadria. 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ a b Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1900 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1900. pp. 50, 66.

- ^ a b Industrie und Gewerbe in Bromberg. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1907. p. 140.

- ^ a b c Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1890 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1890. pp. 60, 72, 86, 174.

- ^ "Lofty z ciekawym wnętrzem". pomorska.pl. Polska Press Sp. z o. o. 5 December 2008. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Mural "Panienka z Okienka"". visitbydgoszcz.pl. Bydgoskie Centrum Informacji. 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ Allgemeiner Wohnungs-Anzeiger fur Bromberg 1855. Bromberg: Verlag von M. Aronsohn's Buchhandlung. 1855. p. 25.

- ^ a b Umiński, Janusz (1996). Bydgoszcz-Przewodnik (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Wyższej Pomorskiej Szkoły Turystyki i Hotelarstwa w Bydgoszczy.

- ^ Romaniuk, Marek (2001). Wieża Bismarcka w Bydgoszczy. Materiały do dziejow kultury i sztuki bydgoszczy i regionu. Zeszyt 6 (in Polish). Bydgoszcz: Pracownia dokumentacji i popularyzacji zabytków wojewódzkiego ośrodka kultury w Bydgoszczy. pp. 79–87.

- ^ Wohnungs-Anzeiger nebst Adress- und Geschäfts-Handbuch für Bromberg und Umgebung : auf das Jahr 1885. Bromberg: Mittlersche Buchhandlung (A. Fromm Nachf.). 1885. pp. 39, 114, XL.

- ^ Książka Adresowa Miasta Bydgoszczy : na rok 1933. Bydgoszcz: Władysław Weber. 1933. p. 88.

- ^ Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1901 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1901. pp. 68, 103.

- ^ a b Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten für 1909 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1909. p. 158.

- ^ Adressbuch nebst allgemeinem Geschäfts-Anzeiger von Bromberg und dessen Vororten auf das Jahr 1905 : auf Grund amtlicher und privater Unterlagen. Bromberg: Dittmann. 1905. pp. 17, 100.

- ^ Bialas, Boguslaw (10 September 2016). "Nowy mural ozdobi Bydgoszcz. Już dziś jego oficjalne odłosnięcie!". bydgoszcz.naszemiasto.pl. Polska Press Sp. z o. o. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ "Nowy mural przy ul. Toruńskiej. Wciąga bydgoskimi legendami". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. 8 September 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2021.

- ^ Wohnungs-Anzeiger nebst Adress- und Geschäfts-Handbuch für Bromberg und Umgebung : auf das Jahr 1886. Bromberg: Mittlersche Buchhandlung (A. Fromm Nachf.). 1886. pp. 164, 185, LVIII.

- ^ a b Adresy Miasta Bydgoszczy na rok 1923. Bydgoszcz: Władysław Weber. 1923. pp. 266, 456.

- ^ "O firmie". stomil-bydgoszcz.pl. STOMIL S.A. 2021. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ Borakiewicz, Wojciech (23 November 2019). "Zaczęło się od Kauczuku. Tak powstawał bydgoski Stomil". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora S.A. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jarocińska-Wilk, Anna (2013). STO(MIL) w słońcu i niepogodzie. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy.

- ^ a b c Żłobińska, Łucja (1995). Bydgoski "Kauczuk" – "Stomil". Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 98–101.

- ^ a b Sudziński, Ryszard (1999). Życie gospodarcze Bydgoszczy w okresie II Rzeczypospolitej Historia Bydgoszczy tom II część pierwsza 1920-1939. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. ISBN 8390132907.

- ^ Sudziński, Ryszard (2004). Życie gospodarcze Bydgoszczy w okresie II Rzeczypospolitej Historia Bydgoszczy tom II część pierwsza 1939-1945. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. ISBN 8392145402.

- ^ a b Praca zbiorowa (2015). Polityka władz radzieckich wobec przemysłu bydgoskiego w latach 1945-1946. Historia Bydgoszczy. Tom III. Część pierwsza 1945-1956. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 103–126, 199–243. ISBN 9788360775448.

- ^ Borakiewicz, Wojciech (8 December 2018). "Dzieci bydgoskiego Stomilu. Pracownicy o zakładzie-matce". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora S.A. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ^ a b Kamosiński, Sławomir (2007). Jakość produkcji, Sławomir Kamosiński, Mikroekonomiczny obraz przemysłu Polski Ludowej w latach 1950-1980 na przykładzie regionu kujawsko-pomorskiego. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie. pp. 180–234. ISBN 9788371774201.

- ^ a b Kulesza, Maciej (28 September 2020). "Bydgoski jaz walcowy z zewnątrz i od kuchni. Unikatowy zabytek". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora S.A. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ Kocerka, Henryk (2005). Historia toru regatowego w Brdyujściu 1912-2004. Kronika Bydgoska XIX. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 317–326.

- ^ "TRMEW". trmew.pl. Crusoe. 2021. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ Januszewski, Stanisław (January 2006). Jaz walcowy u ujścia Brdy do Wisły. Prosto z pokładu. Biuletyn nr 29. Wrocławek: Fundacja Otwartego Muzeum Techniki we Wrocławiu.

- ^ a b c d Narodowy Instytut Dziedzictwa: Rejestr zabytków nieruchomych – województwo kujawsko-pomorskie (PDF). Bydgoszcz: Kujawsko-pomorskie. 30 September 2020.

- ^ a b Kuczma, Rajmund (1993). Mała encyklopedia Bydgoszczy – część hasła "C". Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 58–60.

- ^ Gliwiński, Eugeniusz (2000). Kwatery żołnierskie na bydgoskich cmentarzach. Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 289–296.

- ^ "Rozpoczął się remont kościoła św. Józefa Rzemieślnika". bydgoszcz.wyborcza.pl. Agora SA. 14 August 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2021.

- ^ a b Parucka, Krystyna (2008). Zabytki Bydgoszczy – minikatalog. Bydgoszcz: „Tifen” Krystyna Parucka.

- ^ a b "Miał być kościół a był acetylen". forum.bsmz.org. Bydgoskie Stowarzyszenie Miłośników Zabytków "Bunkier". 17 October 2011. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Historia Fabryki BEFANA". befana.com.pl. Befana company. 2018. Retrieved 2 September 2018.

- ^ Lachamjer, Jerzy (2007). Technologia nitrogliceryny w zakładach Dynamit Nobel A.G. w Bydgoszczy. Kronika Bydgoska XXVIII. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 383–408.

- ^ Adonis, Tatiana (8 July 2014). "Dotacje na remonty zabytkowych kamienic w Bydgoszczy". radiopik.pl. Radio PiK SA. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Diecezja Bydgoska". diecezja.byd.pl. Diecezja Bydgoska. 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-08-02. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

External links

- (in Polish) OT Logistics S.A.

- (in Polish) Bydgoskie Fabryki Mebli S.A.

- (in Polish) Adria Theater

- (in Polish) Vocational woodworking school

- (in Polish) Bite Art festival

- (in Polish) STOMIL Rubber Company

- Hydroelectric plant Company TRMEW

- (in Polish) St. Joseph Parish

- Stomil Bydgoszcz

Bibliography

- (in Polish) Łbik, Lech (1998). Średniowieczne brody i przeprawy na dolnej Brdzie w okolicy Bydgoszczy. Kronika Bydgoska XIX. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 131–145.

- (in Polish) Żłobińska, Łucja (1995). Bydgoski "Kauczuk" – "Stomil". Kalendarz Bydgoski. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłośników Miasta Bydgoszczy. pp. 98–101.

- (in Polish) Siwiak, Wojciech (2003). Wielkopolska Huta Szkła z Czerska Polskiego (lata 1923–1948). Kronika Bydgoska XXIV. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 315–346.

- (in Polish) Licznerski, Alfons (1965). Rozwój terytorialny Bydgoszczy. Kronika Bydgoska II. Bydgoszcz: Towarzystwo Miłosnikow Miasta Bydgoszczy - Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe. pp. 7–16.

- (in Polish) Sławińska, Krystyna (1969). Przemysł drzewny w Bydgoszczy i w okolicy w latach 1871–1914: Prace Komisji Historii t.VI Prace Wydziału Nauk Humanistycznych. Seria C. Bydgoszcz: Bydgoskie Towarzystwo Naukowe.