30 Rockefeller Plaza

| 30 Rockefeller Plaza (Comcast Building) | |

|---|---|

As the Comcast Building, August 2024 | |

| Former names | RCA Building (1933–1988) GE Building (1988–2015) |

| Alternative names | 30 Rock NBCUniversal Building |

| General information | |

| Status | Completed |

| Type | Offices and television studios (NBC) |

| Location | 30 Rockefeller Plaza New York, New York 10112 |

| Coordinates | 40°45′32″N 73°58′45″W / 40.75889°N 73.97917°W |

| Completed | 1933 |

| Owner | NBCUniversal (floors 2–16) Tishman Speyer (all other floors) |

| Height | |

| Roof | 850 ft (260 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 66 |

| Floor area | 2,099,985 sq ft (195,095.0 m2) |

| Lifts/elevators | 60 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Raymond Hood |

| Developer | John D. Rockefeller Jr. |

| Structural engineer | Edwards & Hjorth; H.G. Balcom & Associates |

| Architectural style(s) | Modern, Art Deco |

| Designated | December 23, 1987 |

| Reference no. | 87002591[1] |

| Designated entity | Rockefeller Center |

| Designated | April 23, 1985[2] |

| Reference no. | 1446[2] |

| Designated entity | Facade: Rockefeller Center |

| Designated | April 23, 1985[3] |

| Reference no. | 1448[3] |

| Designated entity | Interior: Lobby |

| Designated | October 16, 2012[4] |

| Reference no. | 2505[4] |

| Designated entity | Interior: Rainbow Room |

| References | |

| [5] | |

30 Rockefeller Plaza (officially the Comcast Building; formerly RCA Building and GE Building) is a skyscraper that forms the centerpiece of Rockefeller Center in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City, United States. Completed in 1933, the 66-story, 850 ft (260 m) building was designed in the Art Deco style by Raymond Hood, Rockefeller Center's lead architect. 30 Rockefeller Plaza was known for its main tenant, the Radio Corporation of America (RCA), from its opening in 1933 until 1988 and then for General Electric until 2015, when it was renamed for its current owner, Comcast. The building also houses the headquarters and New York studios of television network NBC; the headquarters is sometimes called 30 Rock, a nickname that inspired the NBC sitcom of the same name. The tallest structure in Rockefeller Center, the building is the 28th tallest in New York City and the 65th tallest in the United States, and was the third tallest building in the world when it opened.

30 Rockefeller Plaza's massing consists of three parts: the main 66-story tower to the east, a windowless section at the center, and a 16-story annex to the west. The building's design conforms with the 1916 Zoning Resolution; it is shaped mostly as a slab with setbacks primarily for aesthetic value. The facade is made of limestone, with granite at the base, as well as about 6,000 windows separated by aluminum spandrels. In addition to its offices and studios, 30 Rockefeller Plaza contains the Rainbow Room restaurant and an observation deck called Top of the Rock. 30 Rockefeller Plaza also includes numerous artworks and formerly contained the mural Man at the Crossroads by Diego Rivera. The entire Rockefeller Center complex is a New York City designated landmark and a National Historic Landmark, and parts of 30 Rockefeller Plaza's interior are also New York City landmarks.

30 Rockefeller Plaza was developed as part of the construction of Rockefeller Center, and work on its superstructure started in March 1932. The first tenant moved into the building on April 22, 1933, but its official opening was delayed due to controversy over Man at the Crossroads. The Rainbow Room and the observation deck opened in the mid-1930s, and retail space was added to the ground floor in the 1950s. The building remained almost fully occupied through the 20th century and was renamed for GE in 1988. Since the late 1990s, NBC has owned most of the lower floors, while Tishman Speyer has operated the rest of the building. 30 Rockefeller Plaza was extensively renovated in 2014 and was renamed for Comcast in 2015.

Site

Buildings and structures in Rockefeller Center:

30 Rockefeller Plaza is part of the Rockefeller Center complex in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City.[6][7] It was intended as the central structure of Rockefeller Center, both physically and symbolically.[8][9] The land lot is nearly rectangular and covers 107,766 sq ft (10,011.8 m2), bounded by Sixth Avenue (officially Avenue of the Americas[10]) to the west, 50th Street to the north, Rockefeller Plaza to the east, and 49th Street to the south. The site has a frontage of 545 ft (166 m) on 49th and 50th Streets and a frontage of 175.46 ft (53 m) on Sixth Avenue.[6] The main entrance is on Rockefeller Plaza, a private pedestrian street running through the complex, parallel to Fifth and Sixth Avenues.[11][12][13] In front of 30 Rockefeller Plaza's main entrance, below ground level, is the Lower Plaza.[14][15] The building is assigned its own ZIP Code, 10112; it was one of 41 buildings in Manhattan that had their own ZIP Codes as of 2019.[16]

Across Sixth Avenue, the building faces 1221 Avenue of the Americas to the southwest, 1251 Avenue of the Americas to the west, and 1271 Avenue of the Americas to the northwest. Radio City Music Hall, 1270 Avenue of the Americas, and 50 Rockefeller Plaza are directly to the north. Across Rockefeller Plaza are the International Building to the northeast, La Maison Francaise and the British Empire Building to the east, and 1 Rockefeller Plaza and 608 Fifth Avenue to the southeast. In addition, 10 Rockefeller Plaza is to the south.[6] The site was previously part of the campus of Columbia University,[17] which retained ownership of most of the land well after the complex was built.[18]

Holdout buildings

The northwest and southwest corners of 30 Rockefeller Plaza were built around two holdout structures on Sixth Avenue.[19][20] The owners of the parcel on Sixth Avenue and 49th Street, at the southwest corner of 30 Rockefeller Plaza, had demanded an exorbitant price for their property upon learning of the planned skyscraper.[21] The holdout building had contained Hurley's restaurant, which had opened around the 1890s and subsequently became a popular meeting place for NBC performers and executives. The restaurant was later connected by a direct passageway to 30 Rockefeller Plaza's studios.[22] Rockefeller Center acquired the building in the mid-20th century and ended the restaurant's lease in 1975,[23] but the new lessees continued to run Hurley's until 1999.[22] As of March 2022, the holdout building contains Pebble Bar.[24]

The other tenant, who occupied a plot on Sixth Avenue and 50th Street at 30 Rockefeller Plaza's northwest corner, never received a sale offer due to a misunderstanding.[21] The grocer John F. Maxwell would only sell his property at 50th Street if he received $1 million. Because of a miscommunication, the Rockefeller family was told that Maxwell would never sell, and Maxwell himself said that he had never been approached by the Rockefellers.[25][19] Consequently, Maxwell kept his property until his death in 1962, upon which Columbia bought the building;[26] Rockefeller Center purchased the Maxwell family's lease in 1970.[25][19]

Architecture

30 Rockefeller Plaza was designed by the Associated Architects of Rockefeller Center, composed of the firms of Corbett, Harrison & MacMurray; Hood, Godley & Fouilhoux; and Reinhard & Hofmeister. Raymond Hood was the complex's lead architect.[27][28] The Associated Architects designed all of Rockefeller Center's buildings in the Art Deco style.[29] Developed as part of the construction of Rockefeller Center, 30 Rockefeller Plaza opened in 1933 as the RCA Building.[7] 30 Rockefeller Plaza is 872 ft (266 m) tall and was built as a single structure occupying the entire block between Sixth Avenue and Rockefeller Plaza.[8] As of December 2023, the building is the 31st tallest in New York City and the 65th tallest in the United States.[30]

The design was influenced by Rockefeller Center manager John Todd's desire for the building to use its air rights to their maximum potential.[31][32] 30 Rockefeller Plaza rises to a flat roof, unlike some of the other skyscrapers built in New York City around the same time. These included the Chrysler Building, 70 Pine Street, and 40 Wall Street, which used spires to reach their maximum heights.[33] Hartley Burr Alexander, a mythology and symbology professor who oversaw Rockefeller Center's art program, led the installation of artwork throughout the complex.[34][35][36] The building's artwork was designed around the concept of "new frontiers", depicting modern society.[37]

Form

The massing of 30 Rockefeller Plaza is designed in three parts.[9][38][39] The easternmost section contains a 66-story tower[31] with two stories of retail on the west and east.[39] The tower is surrounded by a shorter U-shaped section to the north, west, and south.[33] Some sources give 30 Rockefeller Plaza's height as 70 stories, but this arises from a hyperbolic press release by Merle Crowell, the complex's publicist during construction.[40] At the middle of the site was a windowless nine-story section, which housed NBC's studios.[38][39] The western part of the site steps up again to a 16-story tower.[38][31][39] The western section at 1250 Avenue of the Americas, formerly also known as RCA Building West, is accessed mainly from Sixth Avenue.[41] The facade of the annex rises straight from the sidewalk, with notches at the corners, because the corner lots were private properties at the time of the building's construction in 1935.[42]

The massing was influenced by the 1916 Zoning Resolution, which restricted the height that the street-side exterior walls of New York City buildings could rise before they needed to incorporate setbacks that recessed the buildings' exterior walls away from the streets.[43][33][a] The base of the building could only rise to 120 feet (37 m) before it had to taper to a tower covering 25 percent of the site.[44][33] The eastern tower appeared to violate this principle since it measured 103 by 327 feet (31 by 100 m), but the base measured only 200 by 535 feet (61 by 163 m). The base does not occupy its entire plot, which measures 200 by 670 feet (61 by 204 m).[33] The tower section was recessed so far into the block that it could have risen without any setbacks. Hood decided to include setbacks anyway, as they represented "a sense of future, a sense of energy, a sense of purpose", according to architecture expert Alan Balfour.[46] Above the lowest stories, the north and south elevations rise straight up for 33 stories before setting back gradually.[38] There are three setbacks each on the north, south, and east elevations.[47]

Hood also created a guideline that all of the office space in the complex would be no more than 27 ft (8.2 m) from a window,[48][49] which was the maximum distance that sunlight could permeate the windows of a building at New York City's latitude.[50][51] The setbacks on the northern and southern sides of 30 Rockefeller Plaza allow the building to comply with Hood's guideline.[33][39][52] The setbacks correspond to the tops of the elevator banks inside; this arrangement is repeated on the facade of the International Building.[47] Similarly, 30 Rockefeller Plaza also contains notches at its corners.[47][33] The eastern elevation's setbacks were included exclusively for aesthetic purposes.[52] By contrast, the layout and massing of Rockefeller Center's other buildings were intended to maximize rental profit.[53]

Facade

30 Rockefeller Plaza's limestone facade includes spandrels with quadruple-leaf motifs in a Gothic-inspired style.[54][55] influenced the design of the rest of the complex.[56] The first story is clad with Deer Island granite to a height of 4 ft (1.2 m).[57][58] The remainder of the facade contains Indiana Limestone and aluminum spandrel panels.[58] Some 212,000 cubic feet (6,000 m3) of limestone, 4,100 cubic feet (120 m3) of granite, and 6,000 spandrels were used in the construction. The limestone covered 600,000 square feet (56,000 m2).[59] The limestone blocks are laid slightly irregularly and contain striations for visual effect.[57] In addition, 10.38 million bricks were integrated into the facade.[60]

30 Rockefeller Plaza also had 6,045 windows upon its completion, with 19,700 panes between them, covering 168,340 square feet (15,639 m2) in total. Thirty-six of the windows measured 9 by 16 feet (2.7 by 4.9 m) and were storefront windows. Those on the mezzanine level were composed of 9-by-12-foot (2.7 by 3.7 m) panels flanked by smaller sidelights. Another 165 were casement windows, which had panes measuring 6 by 18 inches (150 by 460 mm); most of these were above the 65th floor. The remaining 5,824 were casement windows measuring 4 by 6 feet (1.2 by 1.8 m).[48] About 5,200 of these windows contained Venetian blinds, which were installed by the Mackin Venetian Blind Company.[61]

Entrances

At street level, the stonework is relatively sparsely decorated.[62][63] The main entrance of 30 Rockefeller Plaza was designed as a loggia of three arches: one at the center, measuring 37 feet (11 m) high by 14 feet (4.3 m) wide, and two on the sides, measuring 27 feet (8.2 m) high by 13 feet (4.0 m) wide.[64][65][66] Lee Lawrie designed the sculptural group Wisdom, A Voice from the Clouds, for the lintels of the three arches.[36][64][65] Lawrie's carved rendering of Wisdom is above the center arch, flanked by Sound on the left and Light on the right.[66][63][67][68] The Wisdom frieze above the entrance is accompanied by an inscription reading "Wisdom and Knowledge shall be the stability of thy times", from Isaiah 33:6 (KJV).[69][70] The sculptural groups are accompanied by polychrome decorations created by Léon-Victor Solon.[66] Lawrie's three renderings are complemented by two limestone bas-reliefs by Leo Friedlander: one of Production on the north elevation and one of Radio on the south elevation.[63][67][71][72]

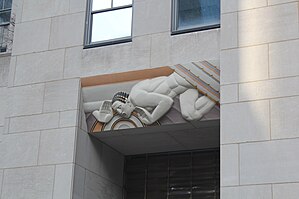

1230 Avenue of the Americas, the annex building to 30 Rockefeller Plaza, contains a marquee[73] and two works of art on its exterior.[74] The recessed entrance portal is filled with a 79 by 14 ft (24.1 by 4.3 m) mosaic mural, Intelligence Awakening Mankind by Barry Faulkner.[75][76][77] The portal is topped by four 11.5 by 4 ft (3.5 by 1.2 m) limestone panels by Gaston Lachaise, each of which signifies an aspect of civilization as it related to the original Radio City complex.[78][79][80] The two panels on either side of the entrance are entitled The Conquest of Space and Gifts of Earth to Mankind; these respectively depict aspiration and life, two qualities that Lachaise believed were most important to humanity.[81] The two panels in the center are known as Genius Seizing the Light of the Sun (also known as Invention Seizing the Light of the Sun[78]) and The Spirit of Progress.[81] The panels are placed at the third story because, at the time of the building's construction, they could be seen from the elevated rail line above Sixth Avenue.[82]

Interior

30 Rockefeller Plaza was designed with about 2,100,000 square feet (200,000 m2) of rentable space in total.[33] The eastern tower contains the Rainbow Room restaurant on the 65th floor,[7] while the Rockefeller family office occupied the tower's 54th through 56th floors until 2014.[83] The tower is the headquarters of NBC[84] and houses NBC Studios, NBC News, MSNBC, and network flagship station WNBC.[83] 30 Rockefeller Plaza also contains offices for NBCUniversal Cable[85] and, until 1988, the NBC Radio Network.[86] Part of NBC's space also extends into the central part of the building.[57][31][87]

The superstructure uses 58,500 short tons (52,200 long tons; 53,100 t) of steel.[33][60] To transport visitors to the top floors, Westinghouse installed eight express elevators in the RCA Building. They moved at an average speed of 1,200 ft/min (370 m/min) and were so expensive that they constituted 13 percent of the building's entire construction cost.[88][89] One elevator reached a top speed of 1,400 ft/min (430 m/min) and was dubbed "the fastest passenger elevator ride on record".[89] These elevators cost about $17,000 a year to maintain by 1942.[90] The mechanical core also contains emergency-exit staircases, though there are fewer staircases on upper floors. For example, building plans indicate that the 12th story has three sets of emergency staircases, while the 60th story has two sets of staircases.[91]

Lobby

The lobby's main entrance is from Rockefeller Plaza to the east, with revolving and double-leaf bronze-and-glass doors underneath a paneled bronze screen.[92] The doors are topped by a cast-glass wall designed by Lee Lawrie, which measures 15 feet (4.6 m) high by 55 feet (17 m) wide.[66][92] The wall is made of 240 glass blocks.[93][38] Each glass block measures 3 inches (76 mm) deep and 19 by 29 inches (480 by 740 mm) across.[66][92] Opposite the main entrance doors is an information desk made of Champlain gray marble. Four large ivory-marble piers with embedded light fixtures support the ceiling immediately above.[92]

The lobby continues north and south from the information desk. Stairways at either end lead up to the mezzanine, while stairs and escalators lead downstairs to the basement. Extending west from either end are two corridors, which flank five north–south elevator banks.[94] The elevator doors are made of bronze, and there are bronze and glass storefronts on the outer walls of these corridors.[95] The floor is made of brass-and-terrazzo mosaic.[71] The walls of these corridors are paneled in Champlain marble below the height of the storefronts and elevator doors.[92][71] A bronze molding runs above the storefronts and elevators, while the walls are made of plaster above that height. The outer walls of the west–east corridors (adjacent to the mezzanines) contain bronze service doors, while the inner walls and the elevator-bank walls contain murals. The ceilings of the corridors are carried by rows of piers.[92]

West of the elevator banks, two north–south corridors extend to side entrances on 49th and 50th Streets, which each contain two bronze sets of revolving doors.[96] The corridors continue west to the Sixth Avenue entrance.[39] Just west of the elevators, a staircase leads down to the basement and up to the NBC lobby.[39][96] The stair to the basement contains Champlain marble and ivory marble, while the stair to the mezzanine contains Champlain marble and bronze railings and moldings. Additional stairs to the basement and mezzanine are placed at the point where the corridors continue into 1250 Avenue of the Americas; they also contain Champlain marble and bronze railings and moldings.[39]

Lobby art

Josep Maria Sert was originally hired to paint four murals in the northern lobby corridor: Time; Spirit of Dance; Man's Triumph in Communication; Conquest of Disease; Abolition of Bondage; Fraternity of Men; and Contest-1940, depicting different aspects of the world and mankind.[97][98] Frank Brangwyn painted four murals on the southern corridor, all of which symbolize humans' relationship with spirituality; he complemented these murals with stencils of the themes that were represented.[99][95] Rockefeller Center's managers had asked Brangwyn to omit a depiction of Jesus Christ from one of the panels;[100][101] the artist ultimately depicted Jesus with his back turned.[102] Brangwyn's and Sert's corridor murals measure 17 by 25 feet (5.2 by 7.6 m) each.[103] Architectural writer Robert A. M. Stern described Brangwyn's murals as "insipid", a quality worsened by the fact that the themes were stenciled onto the murals. By contrast, Stern said: "Sert at least allowed the meaning of his paintings to fall into happy obscurity."[104]

After the building had opened, Sert was commissioned to paint the mural American Progress at the center of the lobby,[93][105][106] measuring 50 by 17 feet (15.2 by 5.2 m).[107] The mural was installed in 1937.[108][109][37] It depicts a vast allegorical scene of men constructing modern America and contains figures of Abraham Lincoln, Mahatma Gandhi, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[105][110][92] The space occupied by American Progress was originally taken up by Diego Rivera's Man at the Crossroads mural,[93][106][111][112] which was controversial because of its communist imagery and was destroyed in 1934.[113][114] Rockefeller officials commissioned a sixth mural from Sert, representing the past, present, and future, which they installed in the lobby in 1941.[49][115] The mural measures 100 by 50 feet (30 by 15 m) and is installed on the ceiling.[92][116]

Concourse and mezzanine

Below the lobby is the complex's shopping concourse,[12][117] connected to the lobby via escalators.[92] The building has a direct entrance to the New York City Subway's 47th–50th Streets–Rockefeller Center station via the concourse.[118] Until 1950, the building's concourse had also contained Rockefeller Center's post office.[119]

The mezzanine contains balconies overlooking the lobby. The floors of the mezzanine are black terrazzo, while the walls are made of marble and plaster separated by a bronze molding. Offices from the outer walls open onto the mezzanine balconies. There are staircases from the lobby to both the concourse and mezzanine, west of the lobby's elevator banks.[120] When the building opened, it contained a rotunda at the mezzanine level, measuring 67 feet (20 m) across with a photomural surrounding it. The mural was taken apart in the 1950s and the rotunda itself was demolished in the 1970s.[121] A new rotunda was constructed from 2014 to 2015, accessed from the ground floor by a 16-foot-wide (4.9 m) staircase; the rotunda contains two LED displays, each measuring 60 feet (18 m) wide and 5 feet (1.5 m) tall.[121][122] From 1960 to October 1993, the building's mezzanine level housed the New York City weather forecast office of the National Weather Service.[123] The mezzanine level also contained a control room, from which all of Rockefeller Center's mechanical systems could be monitored.[124]

NBC Studios and headquarters

When the building was constructed, RCA's chief engineer O. B. Hanson was faced with designing an area of the building that was large enough to host 35 studios with as few structural columns as possible. As such, the studios were all placed in the windowless center section of the building, which would have otherwise been used as an unprofitable office space.[31][87] The central part of the building could also use fewer columns, which was suitable for large broadcast studios but not for the bases of skyscrapers.[57] Over 1,500 mi (2,400 km) of utility wires stretched through this part of the building, which was powered by direct current.[87] Two floors were reserved for future TV studios, and five more stories were reserved for audience members and guests.[87] The floor, wall, and ceiling surfaces of the studios were suspended from the superstructure, insulating the studios.[38] In addition, there were double- and triple-height spaces for exhibitions, plays, and other events.[57]

NBC, ABC, and CBS (collectively the Big Three TV Networks) had offices on Sixth Avenue and studios in Midtown during the mid-20th century.[125] The first television shows at the NBC Studios were broadcast from studio 3H in 1935, and more TV studios were added after World War II as television gained popularity.[85] During the RCA Building's early years, NBC housed both the Red Network and the Blue Network (now ABC) there,[126] and WJZ-TV (now WABC-TV) and WJZ Radio (now WABC), as well as the headquarters of the ABC network, were also headquartered there for the first few years until ABC built their own facilities.[127] When the building opened, it also hosted daily tours of the NBC Studios;[128][129] the tours were canceled in 1977 due to declining attendance.[128] NBC was the only one of the Big Three that retained studios in Midtown by the mid-1980s.[125]

Studio 8H, which hosts Saturday Night Live,[130][131] is the largest of the studios at 30 Rockefeller Plaza, with a capacity of 1,200[132] or 1,400 guests.[133] Studio 8H was once the largest radio studio in the world and was originally home to the NBC Symphony Orchestra[134] before being converted into a television studio in 1950.[135][132] Another major studio at 30 Rockefeller Plaza is Studio 6B, which hosted Texaco Star Theater, the first comedy-variety show on television to become popular.[136] The Tonight Show was also broadcast from Studio 6B until 1972, returning there in 2014 under the name The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon.[137][138] Tonight's companion program, Late Night (branded Late Night with Seth Meyers since 2014) is also taped in the building.[139] The Today Show was also broadcast from 30 Rockefeller Plaza until 1994, when it moved to 10 Rockefeller Plaza.[140]

Rockefeller family offices

The Rockefeller family's office, Room 5600, occupied the entire 56th floor.[141] The family's Rockefeller Foundation rented the entire floor below, and two other organizations supported by the Rockefellers also moved into the building.[141][142] Daniel Okrent, author of the book Great Fortune: The Epic of Rockefeller Center, said the Rockefellers' offices resembled an "18th-century English baronial mansion".[82] The space was decorated with art by Paul Gauguin, Piet Mondrian, Paul Signac, and Joan Miró.[143]

By 1937, there were 392 employees of Room 5600. After World War II, Room 5600 comprised the entire 54th through 56th floors.[144] The family offices became a hub for the family's political activity, with ties to both the Democratic and Republican parties at the city, state, and national levels.[145] Visitors to Room 5600 have included Frank Sinatra, Shirley MacLaine, Nelson Mandela, Richard Gere, and Bono.[83] Even in the late 1980s, when Room 5600 had downsized to 175 people, it still managed $900 million of Rockefeller family wealth.[146] The family moved out during 2014.[83][143]

Rainbow Room

The 65th floor of the building is an event room and restaurant named the Rainbow Room.[147] The space was designed by Wallace K. Harrison of Associated Architects.[148] Interior designer Elena Bachman Schmidt, a one-time apprentice of Elsie de Wolfe, contributed to the design of the interior decor, such as the furniture, curtains, and elevator doors. Vincente Minnelli was assigned to help Schmidt select the colors of the walls.[149][150] The restaurant opened in 1934,[151][152] and was the highest restaurant in the United States for decades, though it was closed during much of the 1940s.[153] The most recent version of the restaurant opened in 2014 after a restoration by Gabellini Sheppard Associates.[154]

The Rainbow Room occupies the eastern part of 30 Rockefeller Plaza's 65th floor, which covers 13,500 square feet (1,250 m2).[155][156][157] The central part of the floor has elevator banks, restrooms, a gallery, and a private dining room. The western part houses Bar SixtyFive and an outdoor terrace.[156] The dining room itself is a 4,464-square-foot (414.7 m2) space.[156][158] The restaurant has a 32-foot-wide (9.8 m) rotating dance floor.[159][160] The seats of the Rainbow Room are organized in tiers,[159] and there is also a platform for bands and a shallow balcony for entertainers.[156][159] There are stairs and a dumbwaiter behind the platform,[159] as well as several banquet rooms on the 64th floor.[161] Above the dance floor hang several concentric "rings" that recess into the ceiling.[159]

Roofs

Garden of the Nations

The roof of the building's central section contained a 0.75-acre (0.30 ha) "Garden of the Nations" (alternatively "Gardens of the Nations"[53]), which opened in April 1935 on the 11th floor.[162][56][163] The garden used 3,000 short tons (2,700 long tons) of soil; 100 short tons (89 long tons) of rock from as far as England; 100,000 bricks; 2,000 trees and shrubs; 4,000 small plants; and 20,000 bulbs for flowers.[164] Originally, the garden included thirteen nation-specific gardens, whose layouts were inspired by gardens in the respective countries they represented. Each of the different gardens were separated by barriers.[162] The "International Garden", a rock garden in the center of the themed gardens,[165] featured a meandering stream and 2,000 plant varieties.[166] The Garden of the Nations also contained a children's garden, a modern-style garden, and a shrub-and-vegetable patch.[167] The garden was staffed by hostesses who wore costumes, and the plantings lit up at night.[168]

Ralph Hancock and Raymond Hood designed the rooftop garden,[169][164][165] one of several in the complex.[170] Upon opening, the Garden of the Nations attracted many visitors because of its collection of exotic flora,[171] and it became the most popular garden in Rockefeller Center.[172] In its heyday, the Center charged admission fees for the Garden of the Nations.[169][173] However, the nation-themed gardens were demolished by 1938,[169][168] and the rock garden was left to dry up, supplanted by flower beds that were not open to the public.[173] In 1936, the central roof temporarily housed a prototype of an apartment, which was used to advertise the Rockefeller Apartments between 54th and 55th Streets.[174][175]

Primary roof

From 1937 onward, the roof of the eastern tower contained neon letters spelling "RCA".[176] The letters each measured 22 feet (6.7 m) wide by 24 feet (7.3 m) tall;[177] at the time of the building's completion, the letters were the world's highest neon signs.[178] These were replaced by "GE" letters in 1988.[179][180] The letters were replaced again with the new united Comcast/NBC logo, rendered in longer-lasting LED lighting.[83] The new signs consist of a 10 ft (3.0 m) tall Comcast wordmark and NBC logo on the northern and southern elevations, as well as a 17 ft (5.2 m) NBC logo on the building's western elevation.[181]

In 1960, a 12-foot-wide (3.7 m), 400-pound (180 kg) weather radar dish for the National Weather Service was installed atop the roof when the building became the NWS's headquarters.[182][183] KWO35, the NOAA Weather Radio station serving the majority of the Tri-State area, transmitted from atop the building and remained there until 2014. Due to interference with a U.S. Coast Guard radio channel, the transmitter was eventually relocated atop the MetLife Building.[184][185] The weather radar station was used as Doppler 4000 during WNBC-TV's local newscasts.[186] It was operational until February 1, 2017, when StormTracker 4, an S-band weather radar at Rutgers University's Cook Campus, started operating.[187]

Observation deck

Top of the Rock, the 70th-story observation deck atop the skyscraper, opened in 1933 and is 850 feet (260 m) above street level.[170][188][189] In addition to the deck, the attraction includes a triple-story observatory on the 67th to 69th floors.[189] Top of the Rock competes with the 86th-floor observation deck of the Empire State Building 200 feet (61 m) higher, as well as a distant view of the Empire State Building.[190] Top of the Rock is accessed from its own entrance on 50th Street, where two elevators (converted from freight elevator shafts) ascend to the 67th floor.[191] The shafts are illuminated, while the elevator cabs contain ceiling panels with historical photographs.[189] There is a double-height indoor observatory on the 67th floor, where escalators lead to the 69th floor. A 8.5-foot-tall (2.6 m) parapet of frameless safety glass runs around the perimeter of the deck; it dates to the 2005 renovation.[191]

The deck originally had dimensions of 190 by 21 feet (57.9 by 6.4 m)[188] and was decorated in the style of an ocean liner, with furnishings such as slatted chairs.[189] The observation deck was closed in 1986 because a renovation of the Rainbow Room had cut off the deck's only access point.[192] The observation deck has been known since 2005 as Top of the Rock, when it reopened after a renovation by Gabellini Sheppard Associates.[191] The original limestone and cast aluminum architectural details were conserved.[193] In 2011, the observation deck had 2.5 million visitors a year and grossed $25 million.[194] On the 69th story is the Beam, a ride themed to the photograph Lunch Atop a Skyscraper.[195][196] The ride faces Billionaires' Row to the north; it can fit seven riders,[197] and it rotates 12 feet (3.7 m) above the 69th-story terrace.[195][196] As of 2024, the 70th story includes a rotating "skylift" ride,[198][199] as well as spherical rooftop beacon and floor tiles with a celestial pattern.[200][201]

History

Development

Planning

The construction of Rockefeller Center occurred between 1932 and 1940[b] on land that John D. Rockefeller Jr. leased from Columbia University.[204][205] The Rockefeller Center site was originally supposed to be occupied by a new opera house for the Metropolitan Opera.[206] By 1928, Benjamin Wistar Morris and designer Joseph Urban were hired to come up with blueprints for the house.[207] However, the new building was too expensive for the opera to fund by itself, and it needed an endowment.[28] The project ultimately gained the support of John D. Rockefeller Jr.[28][208] The planned opera house was canceled in December 1929 due to various issues, with the new opera house eventually being built at Lincoln Center, opening in 1966.[209][210][211]

With the lease still in effect, Rockefeller had to quickly devise new plans so that the three-block Columbia site could become profitable. Raymond Hood, Rockefeller Center's lead architect, came up with the idea to negotiate with the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) and its subsidiaries, National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and Radio-Keith-Orpheum (RKO), to build a mass media entertainment complex on the site.[212][213] By May 1930, RCA and its affiliates had made an agreement with Rockefeller Center managers. RCA would lease 1,000,000 sq ft (93,000 m2) of studio space; get naming rights to the western part of the development; and develop four theaters, at a cost of $4.25 million per year.[214] A skyscraper at 30 Rockefeller Plaza's current site was first proposed in the March 1930 version of the complex's blueprint,[215] and the current dimensions of the tower were finalized in March 1931.[216][217] The skyscraper would be named for RCA as part of the agreement;[214] the RCA name became official in May 1932.[218]

Construction

The designs for Radio City Music Hall and the RCA Building were submitted to the New York City Department of Buildings in August 1931, by which time both buildings were to open in 1932.[219] Work on the steel structure of the RCA Building started in March 1932.[202] Several artists were hired to design artwork for the RCA Building.[220] Lee Lawrie was hired to design the RCA Building's eastern entrance in June 1932, at which point the sunken plaza in front of the building was also announced.[64][65] The next month, Barry Faulkner was commissioned to create a large glass mosaic on the western entrance facing Sixth Avenue.[75] Gaston Lachaise received the commission for bas-reliefs on the Sixth Avenue entrance in September 1932.[78] The same month, Hood and the complex's manager John Todd traveled to Europe to interview five artists for the lobby.[104] Frank Brangwyn, Josep Maria Sert, and Diego Rivera were hired the following month,[104][221] despite John Rockefeller Jr.'s hesitance to hire Rivera, a prominent communist.[104][222] Henri Matisse had been reluctant to commission a highly visible lobby mural, and Pablo Picasso had refused to even meet with Hood and Todd.[104][223]

Installation of the exterior stonework began in July 1932 and proceeded at a rate of 2,000 cubic feet (57 m3) per day.[224] Window installation began the same month.[48] The building's structural steel was up to the 64th floor by September 16, 1932.[225][81] The photograph Lunch atop a Skyscraper was taken on September 20, 1932, during the construction of the 69th floor;[226][227] it was part of a publicity stunt promoting the RCA Building.[228] The building was topped out on September 26, 1932, when an American flag was hoisted to the top of the primary 66-story tower on Rockefeller Plaza. The Indiana limestone cladding had been erected to the 15th floor on the Rockefeller Plaza wing, and the facade of the Sixth Avenue wing had been completed.[224] The stone was fabricated at four factories in New York state and then shipped to New York City. Two traveling cranes lifted the stone from the ground to two hoists 70 feet (21 m) high, which then raised the stone to the upper floors.[59] The stonework of the primary tower was completed on December 7, 1932, without fanfare.[59][229] Officials said at the time that they did not host a ceremony for the stonework's completion because the elevators only ran to the 55th floor.[229] It had taken only 102 workdays to install the 212,000 cubic feet (6,000 m3) of stonework.[59]

Rockefeller Plaza was added to the city's official street map in January 1933, and the RCA Building gained the address 30 Rockefeller Plaza.[11] The next month, John D. Rockefeller III honored 27 mechanics for their work on the RCA Building.[230][231] At the time, The New York Times reported that 1,600 workers were busy completing the interior work. According to the main contractors, the laborers, plasterers, and metal lathers involved in the project would need to be compensated the equivalent of 25,000 eight-hour workdays. The building would require 26,900 short tons (24,000 long tons; 24,400 t) of plasterwork, covering about 650,000 square yards (540,000 m2).[232] By April 6, 1933, there were 1,400 mechanics working to complete the RCA Building, which was 90 percent complete; the upper floors were mostly finished, but the base was still incomplete.[233] As late as April 24, more than 1,000 workers were still fitting out the RCA Building.[234][235] As a result of the Depression, building costs were cheaper than projected. The final cost of the first ten buildings, including the RCA Building, came to $102 million (equivalent to $1.8 billion in 2023 dollars[236]).[237]

Opening and early years

Todd, Robertson, Todd Engineering Corporation, which was constructing Rockefeller Center, relocated to the RCA Building on April 22, 1933, becoming the first tenants.[234][235] The RCA Building was slated to officially open on May 1, 1933.[238] Its opening was delayed until mid-May because of a controversy over Rivera's Man at the Crossroads,[239] which in large part stemmed from the communist motifs of the mural.[240] On May 10, 1933, Rivera was ordered to stop all work on the mural,[241][242] which was covered in stretched canvas and left incomplete.[241][240][243] Brangwyn's murals were also incomplete at the time of the building's opening.[100] Rivera's mural remained covered until February 1934, when workmen peeled the mural off the wall.[114] Columbia University originally owned most of Rockefeller Center's land as well as the complex's buildings, including the RCA Building. However, Columbia received no rental income; Rockefeller Center's managers collected the rent and owned the land under the western part of the complex, including a section of the RCA Building West.[205]

The RCA offices moved to the RCA Building's 52nd and 53rd floors in June 1933.[244] The Rockefeller family took up space throughout the building to give potential tenants the impression of occupancy.[245][246] Their Rockefeller Foundation, as well as the General Education Board and the Spelman Fund of New York, had leased space,[247][246] and the Rockefeller family's Standard Oil Company moved into the RCA Building in 1934.[248] NBC was one of the first tenants in the new RCA Building and, with 35 studios packed into the base, it was also one of the largest tenants.[249] Westinghouse moved into the 14th through 17th floors of the RCA Building,[245][250] receiving the contract for the building's elevators as a result.[251] American Cyanamid took four floors and part of another.[252][253] Other space was taken by the Greek consulate,[254] the Chinese consulate,[255] the National Health Council,[256] and a branch of the Chase National Bank.[257] A double-height space at the center of the ground story, which had been difficult to rent, opened as the Municipal Art Exhibition in February 1934.[258][259] The space, referred to as the Forum,[260] had contained a large stairway leading up to a second-story balcony with exhibition rooms.[261] Despite the large number of tenants, Rockefeller Center was only 59 percent rented by the end of 1933.[251]

Shortly after the RCA Building's opening, there were plans to use the building above the 64th floor as a public "amusement center". That section of the building had several terraces, which could be used as a dance floor, observation deck and landscaped terrace gardens.[262][263] On the 65th floor, there was also a two-story space for a dining room with a high ceiling.[264] Frank W. Darling quit his job as head of Rye's Playland[265] to direct the programming for the proposed amusement space.[262][263] In July 1933, the managers opened an observation deck atop the RCA Building, which consisted of 190 by 21 ft (57.9 by 6.4 m) terraces on the 67th, 69th, and 70th floors.[188] The 40-cents-per-head observation deck saw 1,300 daily visitors by late 1935.[266] Meanwhile, the floors below the observation deck were planned as a restaurant, solarium, game room, and ballroom, which would later become the Rainbow Room.[188] The Rainbow Room opened on October 3, 1934.[151][152]

A revolving beacon was installed atop 30 Rockefeller Plaza in 1935, the first such beacon to be installed in Manhattan.[267] That September, the ground-floor retail space was fully leased.[268] The New York Museum of Science and Industry leased the Municipal Art Exhibition space shortly afterward after Nelson Rockefeller became a trustee of the museum.[269][270] Subsequently, Edward Durell Stone removed the partitions on the second floor of the exhibition space,[261] and the museum opened there in February 1936.[271][272] The central wall of the main lobby remained empty until 1937, when Jose Maria Sert's American Progress was installed.[108][109] At the time, the RCA Building was 84 percent leased.[273] By 1938, the NBC studios at the RCA Building received 700,000 annual visitors, while the observation deck had 430,000 annual visitors.[274]

1940s to 1970s

Two 24-ton cooling machines were installed in the basement of the RCA Building in 1940. The air-conditioning units supplemented the RCA Building's existing units and also served 1230 Sixth Avenue, 10 Rockefeller Plaza, and 1 Rockefeller Plaza.[275] The lobby was then renovated in 1941. As part of the project, an overpass at mezzanine level was removed, the lighting was brightened, and another mural by Jose Maria Sert was installed.[116] An air-raid siren was installed atop 30 Rockefeller Plaza in 1942 during World War II.[276][277] The Rainbow Room and Grill atop the RCA Building was closed at the end of that December because of staffing shortages.[278][279] In 1943, Rockefeller Center's managers purchased the lots at 1242–1248 Sixth Avenue and 73 West 49th Street, part of RCA Building West; these lots had previously been held under a long-term lease.[280] By the next year, the RCA Building was almost fully rented.[251][281]

During the war, the RCA Building's Room 3603 became the primary location of the U.S. operations of British Intelligence's British Security Co-ordination, organized by William Stephenson. It also served as the office of Allen Dulles, who later headed the Central Intelligence Agency.[282][283] The revolving beacon, which had been darkened during the war, was reactivated in 1945 after the air-raid siren was dismantled,[284] but the Rainbow Room restaurant remained closed until 1950.[153][285] The Museum of Science and Industry moved out of the RCA Building's lower floors in 1950. Rockefeller Center's managers hired Carson and Lundin to design two new levels of retail space with about 10,000 square feet (930 m2) of new floor area.[286] The retail space was twice as profitable as the museum; the remaining street-level space was transformed into a studio for the Today Show.[287] In mid-1953, Columbia bought all of Rockefeller Center's land along Sixth Avenue, including the western part of RCA Building West, for $5.5 million. Rockefeller Center then leased the land back from Columbia.[288][289][290]

The building's largest tenants, RCA and NBC, renewed their leases in 1958 for 24 years.[291] The National Weather Service's radar was placed on the roof in June 1960, adjacent to RCA's and NBC's antennas,[182][292] and the NWS offices relocated to the building that December.[293] The Singer Manufacturing Company became another major tenant, leasing six floors in 1961;[294][295] this required the installation of a dedicated air-conditioning system on the 58th floor for that company.[296] In addition, the Rainbow Room atop the building was refurbished in 1965.[297] An anti-Vietnam War bombing occurred on the 19th floor in 1969, causing substantial damage, though no one was hurt.[298][299] Also in 1969, the RCA sign atop the building was updated with RCA's new logo in neon lights.[178] The RCA Building maintained high occupancy through this time. Even at its lowest point during the 1973–1975 recession, the building was 88 percent occupied and Rockefeller Center's managers were able to lease space at the building above market rate.[251]

In 1973, the RCA sign atop the building was turned off to conserve energy, the first time it had not lit up since World War II.[177] The next January, RCA renewed its lease for 20 years, having previously considered relocating from New York City.[300][301] RCA's chief executive Robert Sarnoff also announced that the company would construct a "management and conference center" atop the central section of the building.[301][302] The conference center would have been designed by Ford & Earl Design Associates and Justin Lamb and would have been powered by solar heat.[174][303] RCA applied for permission to build the conference center in September 1975,[304] but the project was canceled after Sarnoff resigned that December.[305] The RCA Building's central location and consistent upkeep meant that it was 93 percent occupied by 1975, despite a relatively high vacancy rate in New York City office buildings.[306] Several law firms had moved into the building during this time.[307] Singer moved out of the RCA Building in 1978, freeing up a large block of office space,[308] but RCA and NBC renewed their leases on a combined 1.2 million square feet (110,000 m2) two years later.[309]

1980s and 1990s

Columbia University was not making enough money from Rockefeller Center leases by the 1970s,[310] and the university started looking to sell the land beneath Rockefeller Center, including the RCA Building, in 1983.[311] That year, the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) held hearings to determine how much of Rockefeller Center should be protected as a landmark.[312] The Rockefeller family and Columbia University acknowledged that the buildings were already symbolically landmarks, but their spokesman John E. Zuccotti recommended that only the block between 49th and 50th Streets be protected, including the RCA Building and RCA Building West.[c] By contrast, almost everyone else who supported Rockefeller Center's landmark status recommended that the entire complex be landmarked.[314][315][316] The LPC granted landmark status to the exteriors of all of the original complex's buildings, as well as the interiors of the International Building's and 30 Rockefeller Plaza's lobbies, on April 23, 1985.[316][317][318][d] Rockefeller Center's original buildings also became a National Historic Landmark in 1987.[319]

Columbia had agreed to sell the land to the Rockefeller Group, an investment company owned by the Rockefeller family,[320] for $400 million in February 1985.[311][321] The Rockefeller Group formed Rockefeller Center Inc. that July to manage the RCA Building and other properties.[322][320] By late 1985, NBC began planning to relocate, leaving half the RCA Building's space vacant.[323][324] The network needed 1 million square feet (93,000 m2) of space and the RCA Building's facilities required hundreds of millions of dollars in renovations.[323] The same year, General Electric acquired RCA/NBC and began looking to save money.[325] The developers of Harmon Meadow and Television City had both made offers to NBC, but demand for office space in New York City was starting to decrease, which led the building's owners to focus on keeping NBC at the RCA Building.[325][326] NBC agreed to stay at 30 Rockefeller Plaza at the end of 1987 after city and state officials offered $72 million in tax exemptions, $800 million in industrial bonds, and sales-tax deferments on $1.1 billion worth of purchases.[327][328] These incentives would not need to be repaid as long as NBC stayed at the building until 2002, or for 15 years.[327] NBC extended its lease by 35 years so that it would last into 2022 and secured an option to buy the western and central sections of the skyscraper.[328]

Meanwhile, the Rockefeller Group had begun expanding the Rainbow Room. The observation deck closed in 1986 because the expansion cut off the only access between the observation deck and its elevators.[192] The Rainbow Room also reopened in December 1987 after the Rockefeller Group conducted an extensive renovation.[329] The RCA Building was renamed the GE Building in July 1988, and the signage atop the building was changed accordingly, despite concerns that it could be confused with the General Electric Building on 570 Lexington Avenue.[179][180] Mitsubishi Estate, a real estate subsidiary of the Mitsubishi Group, purchased a majority stake in the Rockefeller Group in 1988, including the GE Building and Rockefeller Center's other structures.[330][331] Despite the renaming, 30 Rockefeller Plaza continued to be popularly known as the RCA Building.[178] Subsequently, Rockefeller Center transferred some of the unused air rights above the British Empire Building and La Maison Francaise to the Rockefeller Plaza West skyscraper on Seventh Avenue.[332][333] In exchange, the Rockefeller Group had to preserve the original buildings between 49th and 50th Streets[c] under a more stringent set of regulations than the rest of the complex. While the GE Building's air rights were unaffected, the structure fell under the new regulations.[334]

The Rockefeller Group filed for bankruptcy protection in May 1995 after missing several mortgage payments.[335][336] That November, John Rockefeller Jr.'s son David and a consortium led by Goldman Sachs agreed to buy Rockefeller Center's buildings for $1.1 billion,[337] beating out Sam Zell and other bidders.[338] The transaction included $306 million for the mortgage and $845 million for other expenses.[339] As that sale progressed, GE and Goldman Sachs discussed selling part of the GE Building to its namesake, allowing GE to lower its occupancy costs on the 1,600,000 sq ft (150,000 m2) that it occupied.[340][341] In May 1996, GE bought the space for $440 million, as well as an option to renew the lease on the Today Show studios at 10 Rockefeller Plaza.[342] Before either transaction was finalized, GE subleased 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2) of that space.[343][344] Goldman Sachs made numerous upgrades to the building and allowed brokers to finalize leases more quickly.[251] In addition to GE, other large tenants at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in the late 1990s included law firm Donovan, Leisure, Newton & Irvine and Chadbourne & Parke.[345] Cipriani S.A. took over the Rainbow Room in 1998.[346]

2000s to present

Tishman Speyer, led by David Rockefeller's close friend Jerry Speyer and the Lester Crown family of Chicago, bought the original 14 buildings and land in December 2000 for $1.85 billion, including the GE Building.[339][330] The next year, Tishman Speyer began planning a renovation of the rooftop observation deck, which would be rebranded Top of the Rock.[191] Kostow Greenwood Architects also started designing a renovation for NBC Studios.[347] The observation deck plans were announced publicly in November 2003.[348] Two existing elevator shafts were lengthened so that the observation deck could be accessed without going through the Rainbow Room to get to the "shuttle" elevators. In addition, a ground-floor entrance was created on 50th Street and a three-level storefront was converted into an observation deck entrance.[191] The deck reopened in November 2005 after a renovation by Gabellini Sheppard Associates.[349][193]

During the late 2000s, the building retained an 85 percent occupancy rate.[251] The WNBC-TV newsroom was renovated during 2008,[350] after NBC had announced earlier the same year that it would start a 24-hour news channel.[351] In addition, Tishman Speyer hired EverGreene Architectural Arts to restore the lobby, and a two-year restoration commenced in 2009.[37] The Rainbow Room closed that year after Rockefeller Center Inc. ended Cipriani's lease,[352] and the LPC designated the Rainbow Room as an interior landmark in 2012.[353] Comcast, which had bought a 51 percent ownership stake in NBCUniversal in 2009,[354] bought the remaining ownership stake from GE in 2013.[355] The sale included NBC's portion of 30 Rockefeller Plaza and the building's naming rights;[355] by then, GE occupied only two stories in the building.[356] The Rainbow Room reopened in October 2014 under new management,[357] and the rotunda above the lobby was restored starting in 2014.[121]

In June 2014, the LPC granted Comcast permission to modify 30 Rockefeller Plaza.[181][358] Comcast planned to rename the building and replace the signage on the roof.[181][178] Additionally, a new marquee was added to the Sixth Avenue entrance, advertising it as the home of The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon.[181][73] The GE signage was dismantled starting in September 2014,[356] and 30 Rockefeller Plaza was officially renamed the Comcast Building on July 1, 2015.[359] Toy store FAO Schwarz opened a store at 30 Rockefeller Plaza in November 2018.[360][361] In April 2022, the LPC approved Tishman Speyer's proposal to install additional visitor attractions at Top of the Rock.[200][201] One of the attractions, the Beam, opened in December 2023,[195][196] while the Skylift ride opened in October 2024.[198][199] That December, Tishman Speyer requested the LPC's permission to replace the neon signage at the building's 49th and 50th Street entrances with LED signage.[362][363]

Impact

As Rockefeller Center was being developed, Variety magazine wrote: "The main building of the Rockefeller Center group is a notable structure and forms a fitting climax to half a decade of super-skyscraper construction, which, with this one exception, was abruptly brought to an end" by the 1929 crash.[33] A Hearst's International magazine article described the RCA Building as "soaring to an incredible petrous peak", with the sunken plaza "shimmering in brilliant floodlight" at its base.[364] After 30 Rockefeller Plaza was completed, the Federal Writers' Project observed in 1939: "Its huge, broad, flat north and south facades, its almost unbroken mass, and its thinness are the features that impelled observers to nickname it the 'Slab'."[39][67] According to the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat, the RCA Building's massing "marked the emergence of a new form of the skyscraper", namely the slab-like form.[49]

Architectural critic Paul Goldberger said, "Nothing is more attuned to romantic fantasies of New York than the RCA Building's black granite lobby, the Rainbow Room's ornamental framing of a 70-story view...".[365] Goldberger wrote that the RCA Building's form was "made sumptuous by its mounting setbacks", contrasting with the "smaller and bulkier" International Building and other structures in the complex.[366] In 2009, a Crain's New York reporter wrote: "NBC, which owns its space, lends the building a certain panache. So do the art, Christmas tree, gardens and immaculate condition of the center."[251]

As the central building of Rockefeller Center, 30 Rockefeller Plaza is widely known.[49] The building was commonly nicknamed 30 Rock,[251][367] which inspired the title of the NBC sitcom 30 Rock (2006–2013).[368][369] Additionally, numerous movies and TV series that feature Rockefeller Center in their establishing shots have used imagery of 30 Rockefeller Plaza.[370] Such films have included Nothing Sacred in 1937, How to Marry a Millionaire in 1953, and Manhattan in 1979.[371] Two films have also discussed the destruction of Rivera's Man at the Crossroads in the lobby: The Cradle Will Rock in 1999 and Frida in 2002.[372] Race Through New York Starring Jimmy Fallon, an attraction at the Universal Studios Florida amusement park, is also based on 30 Rockefeller Plaza's design.[373]

Several later buildings were inspired by 30 Rockefeller Plaza and its design features, including 525 William Penn Place in Pittsburgh (also designed by Harrison & Abramovitz),[374] the Wells Fargo Center in Minneapolis,[375][376] and the NBC Tower in Chicago.[377][378] In particular, the critics Paul Goldberger and Rick Kogan wrote that the NBC Tower's buttresses, setbacks, and vertical stripes were similar to those at 30 Rockefeller Plaza.[378][379] Goldberger also said that the architect John Portman may have used the RCA Building as an inspiration for San Francisco's Embarcadero Center and Atlanta's Peachtree Center but that, in both cases, Portman's towers "look more like sliding planes than the sumptuous, carved-out mountain that the RCA Building's form evokes".[376]

See also

- Architecture of New York City

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan from 14th to 59th Streets

References

Notes

- ^ As per the 1916 Zoning Act, the wall of any given tower that faces a street could only rise to a certain height, proportionate to the street's width, at which point the building had to be set back by a given proportion. This system of setbacks would continue until the tower reaches a floor level in which that level's floor area was 25% that of the ground level's area. After that 25% threshold was reached, the building could rise without restriction.[44] This law was superseded by the 1961 Zoning Resolution.[45]

- ^ 30 Rockefeller Center was the first building to start construction, in September 1932.[202] The last building was completed in 1940.[203]

- ^ a b Namely 1250 Avenue of the Americas, 30 Rockefeller Plaza, the British Empire Building, La Maison Francaise, the Channel Gardens, and the Lower Plaza[313]

- ^ The final exterior landmark designation covers 12 buildings as well as the Channel Gardens, Rockefeller Plaza, and Lower Plaza. These are 1230, 1250, and 1270 Avenue of the Americas; 1, 10, 30, 50, and 75 Rockefeller Plaza; the British Empire Building; the International Building; La Maison Francaise; and Radio City Music Hall.[313]

Citations

- ^ "Rockefeller Center". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. September 18, 2007. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012.

- ^ a b Adams 1985, p. 11.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1985, p. 1.

- ^ a b Postal 2012, p. 1.

- ^ "Emporis building ID 115419". Emporis. Archived from the original on April 22, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b c "1271 Avenue of the Amer, 10020". New York City Department of City Planning. Archived from the original on July 15, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2020.

- ^ a b c White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- ^ a b Krinsky 1978, p. 4.

- ^ a b Reynolds 1994, p. 301.

- ^ Bowen, Croswell (April 1, 1970). "Topics: In Search of Sixth Avenue". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 16, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- ^ a b "' Rockefeller Plaza' Joins City Directory; Center's New Street and Promenade Named". The New York Times. January 16, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ a b Adams 1985, p. 177.

- ^ Krinsky 1978, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Krinsky 1978, p. 64.

- ^ "Rockefeller City to Have Big Plaza" (PDF). The New York Times. June 10, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- ^ Brown, Nicole (March 18, 2019). "Why do some buildings have their own ZIP codes? NYCurious". amNewYork. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ^ "Rockefeller Site For Opera Dropped" (PDF). The New York Times. December 6, 1929. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved November 10, 2017.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen (February 6, 1985). "Columbia Is to Get $400 Million in Rockefeller Center Land Sale". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 10, 2017. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c Okrent 2003, pp. 93–94, map p. 92.

- ^ Alpern & Durst 1996, pp. 38, 40.

- ^ a b Okrent 2003, pp. 88–89.

- ^ a b Kurutz, Steven (February 24, 2022). "Can a Cool Bar Make It in Rockefeller Center?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ Tomasson, Robert E. (October 13, 1975). "An Old Bar Gives Way To an Imitation Old Bar". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Montagner, Anna (March 9, 2022). "Have a Drink at Pete Davidson's New Midtown Bar". PAPER. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ a b Alpern & Durst 1996, p. 38.

- ^ Fowler, Glenn (September 6, 1962). "Tiny Corner in Radio City Is Sold; Investors Get Parcel That One Family Held 110 Years 50th St. Plot, Bought in 1852 for $1,600, Brings $380,000". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ Federal Writers' Project 1939, p. 334.

- ^ a b c Adams 1985, p. 13.

- ^ Robins 2017, p. 112.

- ^ "Comcast Building". The Skyscraper Center. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. October 28, 2015. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved December 18, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Adams 1985, p. 59.

- ^ Krinsky 1978, p. 53.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "New RCA Building of 69 Stories Rivals the Towering Empire State". Variety. Vol. 109, no. 2. December 20, 1932. p. 60. ProQuest 1529011229.

- ^ Krinsky 1978, p. 110.

- ^ "Outline is Drawn of Radio City Art" (PDF). The New York Times. December 6, 1931. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 651.

- ^ a b c Vogel, Carol (July 26, 2009). "Stripping Away the Darkness as Murals Are Reborn". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f "Rockefeller Center". National Register of Historic Places, National Park Service. December 23, 1987. p. 9. Archived from the original on March 20, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 650.

- ^ Okrent 2003, p. 271.

- ^ Adams 1985, pp. 80.

- ^ Adams 1985, p. 77.

- ^ Krinsky 1978, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Kayden & Municipal Art Society 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Kayden & Municipal Art Society 2000, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Balfour 1978, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Reynolds 1994, p. 302.

- ^ a b c "Glaziers Install 19,700 Panes in RCA Building: All Outside Windows Above Ground Floor Fitted' Much Plate Glass Used". New York Herald Tribune. February 24, 1932. p. 30. ProQuest 1240053177.

- ^ a b c d Žaknić, Ivan; Smith, Matthew; Rice, Dolores B.; Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat (1998). 100 of the world's tallest buildings. Gingko Press. p. 126. ISBN 3-927258-60-1. OCLC 40110184.

- ^ Okrent 2003, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Balfour 1978, p. 38.

- ^ a b Balfour 1978, p. 40.

- ^ a b Marshall 2005, p. 125.

- ^ Krinsky 1978, p. 138.

- ^ Karp & Gill 1982, p. 62.

- ^ a b Adams 1985, p. 61.

- ^ a b c d e Reynolds 1994, p. 303.

- ^ a b Adams 1985, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d "Finish Exterior of RCA Skyscraper; Workmen Set Last Stones on Parapet of 70-Story Building in Rockefeller Center". The New York Times. December 8, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 15, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Rockefeller City to Use 39,100,000 Bricks, Enough to Build More Than 2,500 Dwellings". The New York Times. January 1, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Venetian Blinds in RCA Building". The New York Times. April 26, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 15, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Marshall 2005, p. 122.

- ^ a b c Adams 1985, pp. 64–66.

- ^ a b c "Lawrie to Do Entrance for RCA Building: 'Wisdom-- A Voice From the Clouds, the Title for Sculptor's Composition Taken From Proverbs Artist Silent on Work for the Rockefeller Center Proposed Sunken Plaza for Rockefeller Center". New York Herald Tribune. June 10, 1932. p. 17. ProQuest 1114513116.

- ^ a b c "Rockefeller City to Have Big Plaza; New Street and Sunken Square to Be Built at Foot of 70-Story Skyscraper". The New York Times. June 10, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Architectural Forum 1933, p. 275.

- ^ a b c Federal Writers' Project 1939, p. 336.

- ^ Roussel 2006, pp. 55–56.

- ^ Adams 1985, p. 64.

- ^ Roussel 2006, p. 55.

- ^ a b c Architectural Forum 1933, p. 276.

- ^ Roussel 2006, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Carter, Bill (November 25, 2014). "Jimmy Fallon's Name Goes on 30 Rock Marquee". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ Adams 1985, pp. 78–80.

- ^ a b "Huge Glass Mosaic to Adorn RCA Unit; Symbolic Design by Faulkner Will Cover Walls of Loggia in Rockefeller Center". The New York Times. July 13, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Adams 1985, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Roussel 2006, p. 75.

- ^ a b c "Lachaise Designs RCA Building Art; Four Sculptural Panels on 6th Av. Side to Express Spirit of Modern Inventive Progress". The New York Times. September 19, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ Adams 1985, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Roussel 2006, p. 77–78.

- ^ a b c "RCA Building Panel Designs Half Completed". New York Herald Tribune. September 19, 1932. p. 16. ProQuest 1114731116.

- ^ a b Kimmelman, Michael (April 15, 2020). "Rockefeller Center's Art Deco Marvel: A Virtual Tour". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 25, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Roberts, Sam (November 24, 2014). "Why Are Rockefellers Moving From 30 Rock? 'We Got a Deal'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on November 16, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ "Contact Us". NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on September 3, 2017. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Alleman 2013, p. 59.

- ^ Blau, Eleanor (October 8, 1988). "Radio City Without Radio: WNBC Is Gone". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 6, 2022. Retrieved March 12, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Okrent 2003, p. 363.

- ^ Okrent 2003, p. 256.

- ^ a b "Elevator Speeds 1,400 Feet a Minute; Levy Whisked to 65th Floor of RCA Building in Record Time of 37.1 Seconds". The New York Times. July 14, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved December 7, 2017.

- ^ "RCA Rainbow Room Success Under Native Utican" (PDF). Utica Observer. April 26, 1942. p. 6. Retrieved December 7, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ Architectural Forum 1933, p. 278.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1985, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Robins 2017, p. 116.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1985, p. 25.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1985, p. 16.

- ^ a b Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1985, p. 17.

- ^ Roussel 2006, pp. 60–69.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1985, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Roussel 2006, p. 71.

- ^ a b "RCA Building Bars Jesus From Mural; Brangwyn, British Artist, Now Finds Difficulty in Finishing Sermon on Mount Work". The New York Times. September 15, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Art: Symbolization of Christ Causes Misunderstanding". Newsweek. Vol. 2, no. 8. September 23, 1933. pp. 33–34. ProQuest 1796833221.

- ^ "Mural of Christ Hung in Radio City; Figure With Back Turned Is Said to Be Brangwyn's Original Conception". The New York Times. December 5, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Rockefeller Center Murals Show Man's Triumphs". New York Herald Tribune. June 11, 1933. p. F7. ProQuest 1114643367.

- ^ a b c d e Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 652.

- ^ a b Okrent 2003, pp. 319–320.

- ^ a b Marshall 2005, p. 123.

- ^ "Describes 9 Murals for RCA Building; R.M. Hood, Architect, Home on the Rex After Conferring With Painters in Europe". The New York Times. December 23, 1932. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 12, 2022.

- ^ a b "Sert Mural Placed in the RCA Building; Filling of Space That Once Had Disputed Rivera Work Ends Long Controversy". The New York Times. December 21, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "Sert Replaces Rivera Work at RCA Building: Spaniard Executes Mural for Panel Job Abandoned in Row Over Lenin's Head Is Opposite Main Door Sepia Monochrome Is Like His 4 Adjacent Paintings". New York Herald Tribune. December 21, 1937. p. 19. ProQuest 1223337099.

- ^ Roussel 2006, p. 58.

- ^ Balfour 1978, p. 181.

- ^ Okrent 2003, p. 302.

- ^ Okrent 2003, p. 315.

- ^ a b "Rivera RCA Mural is Cut From Wall; Rockefeller Center Destroys Lenin Painting at Night and Replasters Space" (PDF). The New York Times. February 13, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2017.

- ^ "Uncover RCA Murals; Sixth Sert Work in Rockefeller Center Building Is Ready". The New York Times. March 22, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 15, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ a b "RCA Building Lobby Undergoes Changes; Redecoration and Lighting Plan Includes New Sert Mural". The New York Times. January 17, 1941. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ "The Robot City Nobody Sees" (PDF). The New York Times. June 18, 1944. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

- ^ "MTA Neighborhood Maps: Midtown West" (PDF). Metropolitan Transportation Authority. 2018. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- ^ "Post Office to Move; Rockefeller Center Branch to Go to 610 Fifth Ave. Soon". The New York Times. September 5, 1950. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ Landmarks Preservation Commission Interior 1985, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c Dunlap, David W. (June 25, 2014). "At 30 Rock, Recreating Rotunda With a Nod to the Past". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "Lobby Digital Displays – NBC 30 Rockefeller Plaza". Diversified. September 18, 2018. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ "New York, NY – History". National Weather Service. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved May 9, 2015.

- ^ Berger, Meyer (June 18, 1944). "The Robot City Nobody Sees; It lies deep below Rockefeller Center and there many machines work for men". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved February 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Morgan, Tom (August 2, 1986). "Networks' Moves Mark the End of Broadcast Row". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 10, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2022.

- ^ Sterling, C.H.; O'Dell, C. (2010). The Concise Encyclopedia of American Radio. Taylor & Francis. p. 639. ISBN 978-1-135-17684-6. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ "30 Eventful Years". Broadcasting, Telecasting. Vol. 41, no. 15. October 8, 1951. p. 105. ProQuest 1401195186.

- ^ a b "NBC's Guided Tour of Old Studios To Lapse Into Nostalgia Sunday". The New York Times. August 29, 1977. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ Okrent 2003, p. 365.

- ^ "'Saturday Night Live' to return to Studio 8H in Rockefeller Center". TODAY.com. September 10, 2020. Archived from the original on February 25, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 10, 2020). "'Saturday Night Live' to Return Oct. 3 With New Live Episodes". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 25, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Hughes, Allen (January 8, 1980). "Aura of Toscanini to Fill His Studio 8H Tonight; Converted for Television". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 25, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ Okrent 2003, pp. 363–364.

- ^ Bertel, Dick; Corcoran, Ed (September 1972). "Aldo Gisalbert". The Golden Age of Radio. Season 3. Episode 6. Broadcast Plaza, Inc.. WTIC Hartford, Conn. Archived from the original on April 1, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2016.

- ^ "Room for Television". New York Herald Tribune. October 11, 1950. p. 34. ProQuest 1327419390.

- ^ Lovece, Frank (June 3, 1994). "As the Toyota Comedy Festival gets under way, we tour New York's most famous comedy landmarks". Newsday. p. 105. Archived from the original on February 25, 2022. Retrieved February 25, 2022 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Watch 'Tonight Show' studio's makeover in 60 seconds". TODAY.com. March 31, 2014. Retrieved February 25, 2022.

- ^ Carter, Bill (February 16, 2014). "'Tonight' Show Returns to New York After Nearly 42 Years". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 20, 2014. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ White, Peter (August 18, 2020). "'Late Night With Seth Meyers' To Return To Studio On September 8". Deadline. Archived from the original on November 17, 2020. Retrieved January 25, 2021.

- ^ "NBC Will Return 'Today' To Street-Level Studio". Wall Street Journal. November 8, 1993. ISSN 0099-9660. ProQuest 398398868.

- ^ a b Okrent 2003, p. 259.

- ^ "Philanthropies Rent RCA Building Space; Three Organizations Supported by Rockefeller Will Move Headquarters on May 1" (PDF). The New York Times. March 27, 1933. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved November 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Makarechi, Kia (November 24, 2014). "Rockefeller Family Leaving 30 Rockefeller Center for the First Time". Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on September 18, 2020. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ Okrent 2003, p. 386.

- ^ Okrent 2003, p. 388.

- ^ Warren, James (July 23, 1986). "Fortune Takes an Impressive Look Into Pockets of the Rockefellers". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on March 11, 2022. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ "Rainbow Room – New York". zagat.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2014. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ Balfour 1978, p. 24.

- ^ Okrent 2003, p. 368.

- ^ Postal 2012, p. 7.

- ^ a b Postal 2012, p. 8.

- ^ a b "Night Spots-Gardens: Rockefeller Night Spot in RCA Building Makes a Lavish Debut". The Billboard. Vol. 46, no. 41. October 13, 1934. p. 12. ProQuest 1032058796.

- ^ a b Postal 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Fabricant, Florence (October 1, 2014). "A New York Classic Returns". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 7, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- ^ "30 Rockefeller Plaza: 65th Floor, Rainbow Room, SixtyFive". American Institute of Architects. 2017. Archived from the original on February 10, 2018. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Rainbow Room (June 2016). Floor Plan (PDF) (image). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 11, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2022.

- ^ Postal 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Postal 2012, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e Postal 2012, p. 6.

- ^ "Music: Parisienne". Time. October 8, 1934. Archived from the original on January 15, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

- ^ Postal 2012, p. 3.

- ^ a b "Babylon Outdone by RCA's Gardens". New York Post. April 16, 1935. p. 7. Retrieved November 20, 2017 – via Fultonhistory.com.

- ^ Balfour 1978, pp. 125–137.

- ^ a b "New York's "Hanging Gardens"" (PDF). Albany Times-Union. 1934. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ a b "Gardens of the World Atop Radio City; New York Watches the Growth of a New Venture in the Realm of Horticulture" (PDF). The New York Times. September 2, 1934. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 16, 2022. Retrieved November 20, 2017.

- ^ Balfour 1978, p. 53.

- ^ Balfour 1978, p. 52.

- ^ a b Deitz, Paula (December 16, 1982). "Design Notebook". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 13, 2022. Retrieved March 13, 2022.

- ^ a b c Stern, Gilmartin & Mellins 1987, p. 647.

- ^ a b Reynolds 1994, pp. 301–302.

- ^ Krinsky 1978, p. 91.

- ^ Okrent 2003, p. 355.

- ^ a b Adams 1985, p. 186.

- ^ a b Adams 1985, p. 67.

- ^ "Rockefeller Suites Provide Recreation; Excavations Finished and Steel Work Will Start at Once on Apartments" (PDF). The New York Times. March 27, 1936. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2017.

- ^ "Loftiest Sign Is Lighted; Whalen Turns on RCA's 24-Foot Letters Over Rockefeller Plaza" (PDF). The New York Times. June 29, 1937. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 5, 2021. Retrieved November 17, 2017.