Togoland campaign

| Togoland campaign | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the African theatre of World War I | |||||||||

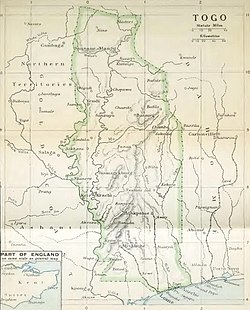

Togoland in 1914 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Frederick Bryant Jean Maroix |

Hans von Doering Georg Pfähler † | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

Gold Coast Regiment Tirailleurs Senegalais | Paramilitary and police forces | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

British: 600 French: 500 |

693–1,500 (including reservists) | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

British: 83 French: c. 54 | 41 | ||||||||

The Togoland campaign (6–26 August 1914) was a French and British invasion of the German colony of Togoland in West Africa, which began the West African campaign of the First World War. German colonial forces withdrew from the capital Lomé and the coastal province to fight delaying actions on the route north to Kamina, where the Kamina Funkstation (wireless transmitter) linked the government in Berlin to Togoland, the Atlantic and South America.

The main British and French force from the neighbouring colonies of Gold Coast and Dahomey (part of French West Africa) advanced from the coast up the road and railway, as smaller forces converged on Kamina from the north. The German defenders delayed the invaders for several days at the Affair of Agbeluvoe (affair, an action or engagement not of sufficient magnitude to be called a battle) and the Affair of Khra but surrendered the colony on 26 August 1914. In 1916, Togoland was partitioned by the victors and in July 1922, British Togoland and French Togoland were established as League of Nations mandates.

Background

Togoland, 1914

The German Empire had established a protectorate over Togoland in 1884, which was slightly larger than Ireland and had a population of about one million people in 1914. A mountain range with heights of over 3,000 ft (910 m) runs south-west to north-east and restricts traffic between the coast and hinterland. South of the high ground the ground rises from coastal marshes and lagoons to a plateau about 200–300 ft (61–91 m) high, covered in forest, high grass and scrub, where farmers had cleared the forest for palm oil cultivation. The climate was tropical, with more rainfall in the interior and a dry season in August.[1]

Half of the border with Gold Coast ran along the Volta river and a tributary and in the south, the border for 80 mi (130 km) was beyond the east bank. The Germans had made the southern region one of the most developed colonies in Africa, having built three metre-gauge railway lines and several roads from Lomé, the capital and main city. There was no port and ships had to lie off Lomé and transfer freight via surfboat. In 1905, a metal wharf equipped with a railway branch was inaugurated by the Germans to receive and trans-ship cargo directly onto trains.[2][3]

The Lomé–Aného railway ran along the coast from Aného to Lomé, the Lomé–Blitta railway connected Lomé and Blitta, serving Atakpamé and the Lomé–Kpalimé railway, ran from Lomé to Kpalimé. Roads had been built from Lomé to Atakpamé and Sokodé, Kpalimé to Kete Krachi and from Kete Krachi to Mango; in 1914 the roads were reported to be fit for motor vehicles.[4] German military forces in Togoland were exiguous; there were no German army units, only 693 Polizeitruppen (paramilitary police) under the command of Captain Georg Pfähler and about 300 colonists with military training.[5]

The colony was adjacent to Allied territory, with French Dahomey on its northern and eastern borders and the British Gold Coast to the west. Dobell called the capital, Lomé and the wireless station at Kamina, about 62 mi (100 km) inland and connected to the coast by road and rail, the only places of military significance. Kamina was near the town of Atakpamé and had been completed in June 1914. The transmitter was a relay station for communication between Germany, its overseas colonies, the Imperial German Navy and South America.[6] The Admiralty wished to prevent the station from being used to co-ordinate German attacks on shipping in the Atlantic. At the outbreak of war the Governor of Togoland, Duke Adolf Friedrich of Mecklenburg, was in Germany and his deputy, Major Hans-Georg von Doering was the acting Governor.[5]

Gold Coast, 1914

Sir Hugh Clifford, the Governor of the Gold Coast, Lieutenant-General Charles Dobell, commander of the West African Frontier Force (WAFF) and Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Rose, commander of the Gold Coast Regiment, were absent during July 1914. William Robertson was the acting-Governor and Captain Frederick Bryant was acting-Commandant of the Gold Coast Regiment.[5][7] The Gold Coast Regiment had one pioneer company, seven infantry companies, with a machine-gun each; a battery of four QF 2.95-inch Mountain Guns, amounting to 1,595 men including 124 carriers and about 330 reservists. There were four "Volunteer Corps" with about 900 men and 1,200 police and customs officers. The Defence Scheme for the Gold Coast (1913) provided for war against the French in neighbouring Ivory Coast and the Germans in Togoland; in the event of war with Germany, the colony was to be defended along Lake Volta and the north-eastern frontier, against raiding, the most that the Germans in Togoland were thought capable of. The plan also provided for an offensive across the lake into the north of Togoland, before making a thrust south to the more populated portion of the colony.[8]

On 29 July 1914, a Colonial Office telegram arrived at Accra, ordering the adoption of the precautionary stage of the Defence Scheme and Robertson forwarded the information to Bryant the next day.[9] Bryant dispensed with the Scheme, which had not been revised after the wireless station at Kamina was built and by 31 July, had mobilised the Gold Coast Regiment along the southern, rather than the northern, border with Togoland.[10] In London, on 3 August, Dobell proposed that if war was declared, an advance would begin along the coast road from Ada to Keta and thence to Lomé, which was less than 2 mi (3.2 km) from the border. Bryant had reached the same conclusion as Dobell and had already organised small expeditionary columns at Krachi and Ada and assembled the main force at Kumasi, ready to move in either direction.[11]

Prelude

Anglo–French preparations

On 5 August, a day after Britain declared war on Germany, the Allies cut the German sea cables between Monrovia and Tenerife, leaving the radio station at Kamina the only connexion between the colony and Germany.[12] The acting-Governor of Togoland, Doering sent a telegram to Robertson proposing neutrality, in accordance with articles X and XI of the Congo Act, which stated that colonies in the Congo Basin were to remain neutral in the event of a conflict in Europe.[13] Doering also appealed for neutrality because of the economic interdependence of the West African colonies and their common interest in dominating local populations.[14] On 6 August, the Cabinet in London refused the offer of neutrality.[15]

Bryant, on his own initiative, after hearing that the French in Dahomey wished to co-operate, sent Captain Barker and the District Commissioner of Keta to Doering, with a demand the surrender of the colony and gave him 24 hours to reply. The next morning the British intercepted a wireless message from Doering that he was withdrawing from the coast to Kamina and that Lomé would be surrendered if attacked.[16] A similar proposal for neutrality from Doering had been received by the Governor of Dahomey, who took it for a declaration of war and ordered an invasion. A French contingency plan to seize Lomé and the coast had been drafted in ignorance of the wireless station at Kamina, only 37 mi (60 km) from the Dahomey border.[17]

Advance to Kamina

Capture of Lomé

Late on 6 August, French police occupied customs posts near Athiémè and next day Major Jean Maroix, the commander of French military forces in Dahomey, ordered the capture of Agbanake and Aného. Agbanake was occupied late on 7 August, the Mono River was crossed and a column under Captain François Marchand took Aneho early on 8 August. The moves were unopposed and Togolese civilians helped to see off the Germans by burning down the Government House at Sebe. The approximately 460 colonists and Askari retreated inland, impressing civilians and calling up reservists as they moved north.[12]

Repairs began on the Aného–Lomé railway and the French advanced to Porto Seguro (now Agbodrafo) and Togo before stopping the advance, once it was clear that Lomé had been surrendered to British forces.[18] The British invasion had begun late on 7 August; the British emissaries returned to Lomé by lorry, to find that the Germans had left for Kamina and given Rudolf Clausnitzer, the Bezirksamtmann of Lomé (equivalent to a British District officer), discretion to surrender the colony up to Khra, 75 mi (120 km) inland, to prevent a naval bombardment of Lomé.[19] On 8 August, the emissaries took command of fourteen British soldiers and police from Aflao; a telegraph operator arrived by bicycle and repaired the line to Keta and Accra.[18]

The British flag was raised and on 9 August, parties of troops arrived, having marched 50 mi (80 km) in exhausting heat. Over the border, Bryant had arranged to move the main force by sea and embarked on the Elele on 10 August. Three other companies had been ordered to Kete Krachi, to begin a land advance to Kamina. Elele arrived off Lomé on 12 August and the force disembarked through the surf.[20][a] Arrangements were made with the French for a converging advance towards Atakpamé by the British and the French from Aného, a French column under Maroix from Tchetti in the north and the British column at Kete Krachi (Captain Elgee). Small British forces on the northern border were put under the command of Maroix and ordered to move south, as about 560 French cavalry were ordered across the northern border from Senegal and Niger, to advance on Mango from 13 to 15 August. The British force at Lomé comprised 558 soldiers, 2,084 carriers, police and volunteers, who were preparing to advance inland when Bryant received news of a German foray to Togblekove.[22]

Skirmish at Bafilo

The skirmish of Bafilo took place between a company of French troops and German Polizeitruppen in north-east Togoland on 13 August. The French had crossed the border between French Dahomey and Togoland from 8 to 9 August and were engaged by German Polizeitruppen in the districts of Mango and Sokodé-Bafilo. The French company retreated after facing greater resistance than expected.[23]

Advance from Lomé

After the capture of Lomé on the coast, Bryant was promoted to lieutenant-colonel, made commander of all Allied forces in the operation and landed at Lomé on 12 August, with the main British force of soldiers, carriers, police and volunteers. As preparations began for the advance northwards to Kamina, Bryant heard that a German party had travelled south by train the day before. The party had destroyed a small wireless transmitter and railway bridge at Tabligbo, about 10 mi (16 km) to the north. Bryant detached half an infantry company on 12 August and sent another 1+1⁄2 companies forward the next day, to prevent further attacks.[24] By the evening, "I" Company had reached Tsévié; scouts reported that the country south of Agbeluvhoe was clear of German troops and the main force had reached Tabligbo.[25]

At 10:00 p.m. "I" Company began to advance up the road to Agbeluvoe. The relatively harsh terrain of bushland and swamp impeded the Allied push to Kamina, by keeping them on the railway and the road, which had fallen into disrepair and was impassable by wheeled vehicles. Communication between the parties was difficult, because of the intervening high grass and thick scrub.[25] The main force moved on from Tabligbo at 6:00 a.m. on 15 August and at 8:30 a.m., local civilians told Bryant that a train full of Germans had steamed into Tsévié that morning and shot up the station.[26] In the afternoon the British advanced guard met German troops near the Lili river, who blew the bridge and dug in on a ridge on the far side.[25][b]

Affair of Agbeluvoe

The demolitions and the delaying action held up the advance until 4:30 p.m.; the force spent the night at Ekuni rather than joining "I" Company as intended.[27] Doering had sent two raiding parties with 200 men south by train, to delay the advancing Allied force.[28] "I" Company had heard the train run south at 4:00 a.m., while halted on the road near Ekuni, a village about 6 mi (9.7 km) south of Agbeluvoe. A section was sent to cut off the train and the rest of "I" Company pressed on to Agbeluvoe. A Togolese civilian guided the section to the railway, where Lieutenant Collins and his men piled stones and a heavy iron plate on the tracks, about 200 yd (180 m) north of the bridge at Ekuni and then set an ambush. One of the trains of 20 cars was derailed by the obstacles on the tracks and the other train was halted by the rest of "I" Company at the Affair of Agbeluvoe. Pfähler was killed and a quarter of the German force became casualties.[29]

Affair of Khra

Despite the skirmish in the north-west at Bafilo and the Affair of Agbeluvoe, Allied forces advancing towards the German base at Kamina had not encountered substantial resistance. The last natural barrier south of Kamina was the Khra River, where Doering chose to make a stand. The railway bridge over the river was destroyed and the approaches to the river and village were mined. On 21 August, British scouts found 460–560 German Polizeitruppen entrenched on the north bank of the river.[30] The West African Rifles, supported by French forces from the east, assembled on the south bank and during 22 August Bryant ordered attacks on the German entrenchments. The British were repulsed and suffered 17 per cent casualties.[31] Lieutenant George Thompson became the first British officer to be killed in action in the First World War.[32]

Although the Germans had repelled the Allied force from an easily supplied, fortified position, French troops were advancing from the north and east towards Kamina unchecked and a British column was advancing on the station from Kete Krachi in the west.[33] On the morning of 23 August, the British found that the German trenches had been abandoned. The Germans had withdrawn to the wireless station and during the night of 24/25 August, explosions were heard from the direction of Kamina. French and British forces arrived at Kamina on 26 August, to find that the nine radio towers had been demolished and the electrical equipment destroyed. Doering and 200 remaining Polizeitruppen surrendered the colony to Bryant; the rest of the German force had deserted.[30] The Allied troops recovered three Maxim machine-guns, 1,000 rifles and about 320,000 rounds of ammunition.[34]

Aftermath

Analysis

Following the outbreak of the war, the wireless station at Kamina passed 229 messages between Germany, the Kaiserliche Marine and colonies before it was demolished.[33] The first military operations of British soldiers during the First World War occurred in Togoland and ended soon after British operations began in Europe.[35] In December 1916, the colony was divided into British and French occupation zones, which cut through the German administrative divisions and civilian boundaries.[36] Both powers sought a new partition and in 1919, during the Paris Peace Conference, Article 22 of the Treaty of Versailles distributed the former German colonies between the Allies.[37]

In July 1922, British Togoland and French Togoland were created from former German colony, as League of Nations mandates.[38] The French acquisition consisted of about 60 per cent of the colony, including the coast. The British received the smaller, less populated and less developed portion of Togoland to the west.[36] The part under British administration united with Ghana upon its independence in 1957; French Togoland gained independence in 1960 as the Togolese Republic.[38] The surrender of Togoland marked the beginning of the end for the German colonial empire, which lost all of its overseas possessions by conquest during the war or under Article 22.[39]

Casualties

The British suffered 83 casualties in the campaign, the French about 54 and the Germans 41. An unknown number of troops and carriers deserted on both sides. Lieutenant George Thompson, 1st Battalion, Royal Scots, was the first British officer killed in the war.[40] Thompson is buried at Walhalla Cemetery near Atakpamé.[41][42] The hospital at Lomé was commandeered and expanded to provide 27 "European" and 54 "native" beds. Four German nurses and 27 other staff, left behind when the Germans withdrew inland, remained at work, supervised by Dr. Le Fanu.[43]

Admissions for sickness during the campaign amounted to 13 Europeans and 53 "natives", 18 of whom were Tirailleurs Sénégalais. Six European and 45 "native" wounded were admitted. Only one wounded man died, despite the Germans using non-military ammunition, which caused severe wounds. Field hospitals were established along the lines of communication and wounded were swiftly evacuated from Khra by an ambulance train, which was running two days after the engagement. Wounded and ill prisoners of war were treated on a ship, supervised by Dr. Berger, a German medical officer.[43]

Notes

- ^ A British patrol near a factory in Nuatja, came into contact with German police and exchanged fire. Private Alhaji Grunshi (who retired after the war as a Regimental Sergeant-Major) is believed to be the first British soldier in the First World War to fire his rifle after hostilities had begun.[21]

- ^ British engineers were quick to build replacement bridges.[25]

Footnotes

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 6.

- ^ "le Wharf de Lomé, ce patrimoine national plein d'histoires!" [The Wharf of Lomé, this National Heritage full of stories!]. Lomegraph (in French). 30 October 2020. Archived from the original on 21 September 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ "Le wharf de Lomé" [The Lomé Wharf]. www goethe de (in French). Archived from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 21 September 2022.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b c Strachan 2004, p. 14.

- ^ Killingray 2012, p. 116.

- ^ Luscombe, Stephen. "Royal Horse Artillery". www.britishempire.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2 October 2022. Retrieved 27 September 2022.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 11.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 9–10, 13.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 13–14.

- ^ a b Friedenwald 2001, p. 11.

- ^ Chappell 2005, p. 7.

- ^ Strachan 2004, p. 15.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 17.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 17–19.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 21.

- ^ a b Moberly 1995, pp. 21–22.

- ^ Marguerat 2004, p. 33.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 21–22, 25–27.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 8.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Schreckenbach 1920, p. 886.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 25–26.

- ^ a b c d Morlang 2008, p. 36.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 26–28.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Fecitte 2012.

- ^ Friedenwald 2001, p. 12; Strachan 2004, p. 17.

- ^ a b Friedenwald 2001, p. 12.

- ^ Morlang 2008, p. 36; Strachan 2004, p. 16.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 36.

- ^ a b Strachan 2004, p. 17.

- ^ Moberly 1995, p. 39.

- ^ Andrew & Kanya-Forstner 1981, p. 61.

- ^ a b Louis 2006, p. 217.

- ^ Strandman 1968, p. 9.

- ^ a b Gorman & Newman 2009, p. 629.

- ^ Strachan 2001, p. 642.

- ^ Moberly 1995, pp. 29, 30–31, 36–39.

- ^ CWGC 2020.

- ^ SA 2017.

- ^ a b Macpherson 1921, pp. 280–281.

References

Books

- Andrew, C. M.; Kanya-Forstner, A. S. (1981). The Climax of French Imperial Expansion, 1914–1924. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-1-84176-401-6.

- Chappell, M. (2005). Seizing the German Empire. The British Army in World War I: The Eastern Fronts. Vol. III. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84176-401-6.

- Gorman, A.; Newman, A. (2009). Stokes, J. (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Peoples of Africa and the Middle East. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 978-0-8160-7158-6.

- Killingray, D. (2012). The Conquest of Togo. Companion to World War I. London: Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-2386-0.

- Louis, W. R. (2006). Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez and Decolonization: Collected Essays. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-309-4.

- Macpherson, W. G. (1921). Medical Services in the United Kingdom, in British Garrisons Overseas and during Operations against Tsingtau, in Togoland, the Cameroons and South-West Africa. History of the Great War based on Official Documents, Medical Services General History. Vol. I. London: HMSO. OCLC 84456080 – via archive.org.

- Moberly, F. J. (1995) [1931]. Military Operations Togoland and the Cameroons 1914–1916. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-89839-235-7.

- Morlang, T. (2008). Askari und Fitafita: "farbige" Söldner in den deutschen Kolonien [Askari and Fitafita: Colored (sic) Mercenaries in the German Colonies] (in German). Berlin: Links. ISBN 978-3-86153-476-1.

- Schreckenbach, P. (1920). Die deutschen Kolonien vom Anfang des Krieges bis Ende des Jahres 1917 [The German Colonies by the Beginning of the War until the end of 1917]. Der Weltbrand: illustrierte Geschichte aus großer Zeit mit zusammenhängendem text (in German). Vol. III. Leipzig: Weber. OCLC 643687370.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. Vol. I (2003 ed.). Oxford: OUP. ISBN 978-0-19-926191-8.

- Strachan, H. (2004). The First World War in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-925728-7.

Journals

- Marguerat, Yves (2004). "La guerre d'août 1914 au Togo: histoire militaire et politique d'un épisode décisif pour l'identité nationale togolaise" [The War of August, 1914 in Togo: Military and Political History of a Decisive episode for Togolese National Identity] (PDF). Patrimoines (No. 14) (in French). Lomé, Togo: Universite de Lomé. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- Strandman, Hartmut Pogge von (1968). "Review: Great Britain and Germany's Lost Colonies, 1914–1919 by Wm. Roger Louis". The Journal of African History. IX (2). Oxford: Clarendon Press: 337–339. doi:10.1017/s0021853700008975. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 179574. S2CID 163085575 – via JSTOR.

Websites

- "Djibouti New European Cemetery". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. 2020. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- Fecitte, H. (2012). "The Soldier's Burden: Togoland 1914". Harry's Africa Web. Archived from the original on 29 November 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- Friedenwald, M. (2001). "Funkentelegrafie Und Deutsche Kolonien: Technik Als Mittel Imperialistischer Politik" [Telegraphy and German Colonies: Imperialist Technology as a Means of Policy] (PDF) (in German). Familie Friedenwald. OCLC 76360477. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 February 2015. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- "South Africa War graves Project: Service details". South African War Graves Project. 2017. Archived from the original on 28 February 2023. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

Further reading

Books

- Buchan, J. (1922). A History of the Great War. Vol. I. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 558495465. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Burg, D. F.; Purcell, L. E. (1998). Almanac of World War I. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-2072-0.

- Dane, E. (1919). British Campaigns in Africa and the Pacific, 1914–1918. London: Hodder and Stoughton. OCLC 150586292. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Klein-Arendt, Reinhard (1995). "Kamina ruft Nauen!" : die Funkstellen in den deutschen Kolonien, 1904–1918 [Kamina calls Nauen!" The Stations in the German Colonies from 1904 to 1918] (in German). Cologne: Wilhelm Herbst Verlag. ISBN 978-3-923925-58-2.

- Längin, B. G. (2005). Die deutschen Kolonien: Schauplätze und Schicksale 1888–1918 [The German Colonies: Scenes and stories from 1884–1918] (in German). Berlin: Mittler. ISBN 978-3-8132-0854-2.

- Margeurat, Y. (1987). Un document Exceptionnel: La Guerre de 1914 au Togo vue par un combattant allemand [An Exceptional Document: The War of 1914 in Togo by a German Soldier] (in French). Lomé: Centre Orstom de Lomé. OCLC 713065710.

- Maroix, Jean Eugène Pierre (1938). Le Togo, pays d'influence franc̜aise [Togo, A Country of French Influence] (in French). Paris: Larose éditeurs. OCLC 2295272.

- O'Neill, H. C. (1918). The War in Africa and the Far East. London: Longmans Green. OCLC 5424631. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- Reynolds, F. J.; Churchill, A. L.; Miller, F. T. (1916). Togoland and the Cameroons. The Story of the Great War. Vol. III. New York: P. F. Collier and Son. pp. 62–63. OCLC 2678548. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- Sebald, P. (1988). Togo 1884–1914: Eine Geschichte Der Deutschen "Musterkolonie" Auf Der Grundlage Amtlicher Quellen [Togo 1884–1914: A History of the German 'Model Colony' from Official sources] (in German). Berlin: Akademie-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-05-000248-4.

Journals

- Esau, Abraham (July 1919). "Die Großstation Kamina und der Beginn des Weltkrieges" [The Great Kamina Station and the Beginning of the World War] (PDF). Telefunken Zeitung (pdf) (in German). III (16) (online 06/2007 by Thomas Günzel for www radiomuseum org ed.): 31–36. OCLC 465338637. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

Websites

- Steward, K. (2006). "Lieut. Colonel FC Bryant CMG CBE DSO Gold Coast Regiment & The short Campaign in Togo August 11–26, 1914" (PDF). British Colonial Africa. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

External links

- L'histoire Vécue : Sokodé, 1914 les Allemands Évacuent le Nord-Togo (French)

- La Guerre de 1914 au Togo vue par un combattant Allemand with campaign map

- Polizeitruppen in Togo and Cameroon with photographs (German)

- Le centenaire de Lomé, capitale du Togo (French)

- An Old Coaster Comes Home: Chapter 5, Rattray's War

- Togoland 1914: The Anglo-French Invasion

- Schutzpolizei uniforms