Titanic conspiracy theories

On April 14, 1912, the Titanic collided with an iceberg, damaging the hull's plates below the waterline on the starboard side, causing the front compartments to flood. The ship then sank two hours and forty minutes later, with approximately 1,496 fatalities as a result of drowning or hypothermia.[1] Since then, many conspiracy theories have been suggested regarding the disaster. These theories have been refuted by subject-matter experts.

Pack ice

The pack ice theory is not a conspiracy theory since it accepts that the sinking was an accident. However, it differs from the commonly accepted theory and is considered implausible by the vast majority of historians. Captain L. M. Collins, a former member of the Ice Pilotage Service, based a conclusion on three pieces of evidence and going off of his own experience of ice navigation and witness statements given at the two post-disaster enquiries, that what the Titanic hit was not an iceberg but low-lying pack ice. His book, called The Sinking of the Titanic: The Mystery Solved (2003) goes into further detail about the events.

- There were no reports of haze the entire night of the sinking, but at 11.30 pm the two lookouts spotted what they believed to be haze on the horizon, extending approximately 20° on either side of the ship's bow. Collins believes that what they saw was not haze but a strip of pack ice, 3–4 mi (4.8–6.4 km) ahead of the ship.[2]

- Each witness had a different description of the ice. 60 ft (18 m) high by the lookouts, 100 ft (30 m) high by Quartermaster Rowe on the deck, and only very low in the water by Fourth Officer Boxhall, on the starboard side near the darkened bridge. "An optical phenomenon that is well known to ice navigators" where the flat sea and extreme cold distort the appearance of objects near the waterline, making them appear to be the height of the ship's lights, about 60 ft (18 m) above the surface near the bow, and 100 ft (30 m) high alongside the superstructure explains what probably happened by the witnesses' descriptions.[3]

- The Titanic made a turn by rotating one-third of the way from the bow, which caused her rudder to hard over and crushed her starboard side into an iceberg. This would have caused the ship to flood, capsize, and sink within minutes, damaging the starboard side of the hull and potentially the superstructure.[4]

Olympic exchange hypothesis

One of the controversial[5][6] and elaborate theories surrounding the sinking of the Titanic was advanced by Robin Gardiner in his book Titanic: The Ship That Never Sank? (1998).[7] Gardiner draws on several events and coincidences that occurred in the months, days, and hours leading up to the sinking of the Titanic, and concludes that the ship that sank was in fact Titanic's sister ship Olympic, disguised as Titanic, as an insurance scam by its owners, the International Mercantile Marine Group, controlled by American financier J.P. Morgan that had acquired the White Star Line in 1902.

Researchers Bruce Beveridge and Steve Hall took issue with many of Gardiner's claims in their book Olympic and Titanic: The Truth Behind the Conspiracy (2004).[5] Author Mark Chirnside has also raised serious questions about the switch theory.[6] British historian Gareth Russell, for his part, calls the theory "so painfully ridiculous that one can only lament the thousands of trees which lost their lives to provide the paper on which it has been articulated." He notes that, "since the sister ships had significant interior architectural and design differences, switching them secretly in a week would be nearly impossible from a practical standpoint. A switch would also not be economically worthwhile, since the ship's owners could have simply damaged the ship while docked (for instance, by setting a fire) and collected the insurance money from that 'accident', which would have been far less severe, and infinitely less stupid, than sailing her out into the middle of the Atlantic with thousands of people, and their luggage, on board, and ramming her into an iceberg".[citation needed]

Deliberately sunk

Another claim, that started gaining traction in late 2017, says that J.P. Morgan deliberately sank the ship in order to kill off several millionaires who were in opposition to the Federal Reserve. Some of the wealthiest men in the world were aboard the Titanic for her maiden voyage, several of whom, including John Jacob Astor IV, Benjamin Guggenheim, and Isidor Straus, were allegedly opposed to the creation of a U.S. central bank.[8] No evidence of their opposition to Morgan's centralized banking ideas has been found –– Astor and Guggenheim never spoke publicly on the subject, while Straus spoke in favor of the concept.[9][10] All three men died during the sinking. Conspiracy theorists suggest that J. P. Morgan, the 74 year-old financier who set up the eponymous banking firm, arranged to have the men board the ship and then sunk it to eliminate them.[11] Morgan cancelled his ticket for Titanic's maiden voyage due to a reported illness. Guggenheim's ticket wasn't even purchased before Morgan's cancellation.[12] Morgan, nicknamed the "Napoleon of Wall Street", had helped create General Electric, U.S. Steel, and International Harvester, and was credited with almost single-handedly saving the U.S. banking system during the Panic of 1907. Morgan did have a hand in the creation of the Federal Reserve, and owned the International Mercantile Marine, which owned the White Star Line, and thus the Titanic.[13]

Morgan, who had attended the Titanic's launching in 1911, had booked a personal suite aboard the ship with his own private promenade deck and a bath equipped with specially designed cigar holders. He was reportedly booked on the ship's maiden voyage but instead cancelled the trip and remained at the French resort of Aix-les-Bains to enjoy his morning massages and sulfur baths.[13] His allegedly last-minute cancellation has fuelled speculation among conspiracy theorists that he knew of the ship's fate.[11][14] This theory has been refuted by Titanic experts George Behe, Don Lynch, and Ray Lepien who have each provided alternate, more widely-accepted theories as to why Morgan cancelled his trip.[15]

Conspiracy theorist Stew Peters has advanced an alternative version of the theory, alleging the Rothschilds were behind both the Federal Reserve and the Titanic’s sinking. Peters also claimed that the Titan submersible implosion was orchestrated via sabotage in order to prevent its own passengers from discovering that the Titanic was sunk by a "controlled demolition" instead of an iceberg.[16]

Closed watertight doors

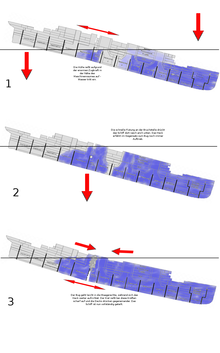

Another theory involves Titanic's watertight doors. This theory suggests that if these doors had been opened, the Titanic would have settled on an even keel and therefore, perhaps, remained afloat long enough for rescue ships to arrive. However, this theory has been rebutted for two reasons: first, the first four compartments were naturally watertight, thus it was impossible to lower the concentration of water in the bow significantly. Second, Bedford and Hacket have shown by calculations that any significant amount of water aft of boiler room No. 4 would have resulted in capsizing of the Titanic, which would have occurred about 30 minutes earlier than the actual time of sinking.[17] Additionally, the lighting would have been lost about 70 minutes after the collision due to the flooding of the boiler rooms.[17] Bedford and Hacket also analyzed the hypothetical case that there were no bulkheads at all. Then, the vessel would have capsized about 70 minutes before the actual time of sinking and lighting would have been lost about 40 minutes after the collision.

Later, in a 1998 documentary titled Titanic: Secrets Revealed,[18] the Discovery Channel ran model simulations which also rebutted this theory. The simulations indicated that opening Titanic's watertight doors would have caused the ship to capsize earlier than it actually sank by more than a half-hour, supporting the findings of Bedford and Hacket.

Expansion joints hypothesis

Titanic researchers continued to debate the causes and mechanics of the ship's breakup. According to his book, A Night to Remember, Walter Lord described Titanic as assuming an "absolutely perpendicular" position shortly before its final plunge.[19] This view remained largely unchallenged even after the wreck was discovered by Robert Ballard in 1985, which confirmed that Titanic had broken in two pieces at or near the surface; paintings by noted marine artist Ken Marschall and as imagined onscreen in James Cameron's film Titanic, both depicted the ship attaining a steep angle prior to the breakup.[20] Most researchers acknowledged that Titanic's aft expansion joint—designed to allow for flexing of the hull in a seaway—played little to no role in the ship's breakup,[21] though debate continued as to whether the ship had broken from the top downwards or from the bottom upwards.

In 2005, a History Channel expedition to the wreck site scrutinized two large sections of Titanic's keel, which constituted the portion of the ship's bottom from immediately below the site of the break. With assistance from naval architect Roger Long, the team analysed the wreckage and developed a new break-up scenario[22] which was publicised in the television documentary Titanic's Final Moments: Missing Pieces in 2006. One hallmark of this new theory was the claim that Titanic's angle at the time of the breakup was far less than had been commonly assumed—according to Long, no greater than 11°.

Long also suspected that Titanic's breakup may have begun with the premature failure of the ship's aft expansion joint, and ultimately exacerbated the loss of life by causing Titanic to sink faster than anticipated. In 2006, the History Channel sponsored dives on Titanic's newer sister ship, Britannic, which verified that the design of Britannic's expansion joints was superior to that incorporated in the Titanic.[23] To further explore Long's theory, the History Channel commissioned a new computer simulation by JMS Engineering. The simulation, whose results were featured in the 2007 documentary Titanic's Achilles Heel, partially refuted Long's suspicions by demonstrating that Titanic's expansion joints were strong enough to deal with any and all stresses the ship could reasonably be expected to encounter in service and, during the sinking, actually outperformed their design specifications.[24] But, most important is that the expansion joints were part of the superstructure, which was situated above the strength deck (B-deck) and therefore above the top of the structural hull girder. Thus, the expansion joints had no meaning for the support of the hull. They played no role in the breaking of the hull. They simply opened up and parted as the hull flexed or broke beneath them.

Brad Matsen's 2008 book Titanic's Last Secrets endorses the expansion joint theory.[25]

One common oversight is the fact that the collapse of the first funnel at a relatively shallow angle occurred when the forward expansion joint, over which several funnels stays crossed, opened as the hull was beginning to stress. The opening of the joint stretched and snapped the stays. The forward momentum of the ship as she took a sudden lurch forwards and downwards sent the unsupported funnel toppling onto the starboard bridge wing.

One theory that would support the fracturing of the hull is that the Titanic partly grounded on the shelf of ice below the waterline as she collided with the iceberg, perhaps damaging the keel and underbelly. Later during the sinking, it was noticed that Boiler Room four flooded from below the floor grates rather than from over the top of the watertight bulkhead. This would be consistent with additional damage along the keel compromising the integrity of the hull.

Fire in coal bunker

This claim states that fire began in one of Titanic's coal bunkers approximately 10 days prior to the ship's departure, and continued to burn for several days into the voyage.[26][27] Fires occurred frequently on board steamships due to spontaneous combustion of the coal.[28] The fires had to be extinguished with fire hoses, by moving the coal on top to another bunker and by removing the burning coal and feeding it into the furnace.[29] This event has led some authors to theorize that the fire exacerbated the effects of the iceberg collision, by reducing the structural integrity of the hull and a critical bulkhead.[30][31]

Senan Molony has suggested that attempts to extinguish the fire – by shoveling burning coals into the engine furnaces – may have been the primary reason for the Titanic steaming at full speed prior to the collision, despite ice warnings.[32] Most experts disagree. Samuel Halpern has concluded that "the bunker fire would not have weakened the watertight bulkhead sufficiently to cause it to collapse."[33][34] Also, it has been alternatively suggested that the coal bunker fire actually helped Titanic to last longer during the sinking and prevented the ship from rolling over to starboard after the impact, due to the subtle port list created by the moving of coal inside the ship prior to the encounter with the iceberg.[35] Some of these foremost Titanic experts have published a detailed rebuttal of Molony's claims.[36]

See also

References

- ^ Shetty, M. R. (1 February 2003). "Cause of death among passengers on the Titanic". The Lancet. 361 (9355): 438. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12423-3. ISSN 0140-6736. PMID 12573421. S2CID 45973512.

- ^ L.M. Collins (2003). The Sinking of the Titanic: The Mystery Solved. Souvenir Press. p. 16. ISBN 0-285-63711-8.

- ^ Collins, 17–18

- ^ Collins, 24–25

- ^ a b Bruce Beveridge and Steve Hall (2004). Olympic & Titanic: The Truth Behind the Conspiracy. Infinity Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7414-1949-1.

- ^ a b Mark Chirnside (2006). "Olympic & Titanic – An Analysis of the Robin Gardiner Conspiracy Theory" (PDF). Retrieved 4 October 2008.

- ^ Robin Gardiner (1998). Titanic: The Ship That Never Sank?. Ian Allan Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-2633-9.

- ^ "The Craziest Titanic Conspiracy Theories, Explained". HISTORY. 22 June 2023. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ "Hoarding by Banks a Cause of Panic; This, Stewart Browne Says, Is the Objection to Aldrich Plan, Which Does Not Stop It". The New York Times. 18 October 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ "Isidor Straus Urges New Banking Plan; Replies to J.J. Hill's Attack on the National Reserve Association Scheme". The New York Times. 16 October 1911. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ a b "The Craziest Titanic Conspiracy Theories, Explained". History.com. 25 February 2019.

- ^ Spilman, Rick (7 September 2020). "QAnon Conspiracy: Did J.P. Morgan Sink the Titanic?". Old Salt Blog. Retrieved 26 September 2024.

- ^ a b Daugherty, Greg. "Seven Famous People Who Missed the Titanic". Smithsonian. Retrieved 8 January 2018.

- ^ "5 wild conspiracy theories surrounding the sinking of the Titanic". Business Insider.

- ^ "Corrected-Fact Check-J.P. Morgan did not sink the Titanic to push forward plans for the U.S. Federal Reserve". Reuters. 17 March 2021. Retrieved 15 January 2023.

- ^ "The RNC is partnering with the Republican Jewish Coalition and Rumble — a virulently antisemitic platform — for the third GOP debate". Media Matters for America. 16 October 2023.

- ^ a b Hacket C. and Bedford, J.G. (1996). The Sinking of the S.S. Titanic – Investigated by Modern Techniques. The Northern Ireland Branch of the Institute of Marine Engineers and the Royal Institution of Naval Architects, 26 March 1996 and the Joint Meeting of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects and the Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in Scotland, 10 December 1996

- ^ famousgir1 (3 April 1998). "Titanic: Secrets Revealed (TV Movie 1998)". IMDb.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Walter Lord (1956). A Night to Remember. Bantam. p. 79. ISBN 0553010603.

- ^ Don Lynch and Ken Marschall (1992). Titanic: An Illustrated History. Hyperion. pp. 136, 139. ISBN 1562829181.

- ^ Robert D. Ballard (1987). The Discovery of the Titanic. Warner Books. ISBN 0446513857.

- ^ "The Break Up". The History Channel. Archived from the original on 3 November 2008. Retrieved 11 November 2008.

- ^ Mark Chirnside. "The Olympic' Class's Expansion Joints". titanic-model.com. Archived from the original on 31 January 2018. Retrieved 19 April 2012.

- ^ JMS Engineering study. "RMS Titanic: Complete Hull Failure Following Collision with Iceberg" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 September 2013. Retrieved 31 December 2012.

- ^ Brad Matsen (October 2008). Titanic's Last Secrets. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 9780446582056.

- ^ Titanic doomed by the fire raging below decks, says new theory – The Independent. 12 April 2008. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ "Titanic Conspiracies". Titanic Conspiracies | Stuff They Don't Want You to Know. 6 October 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ Halpern & Weeks 2011, p. 122.

- ^ Titanic Research & Modeling Association: Coal Bunker Fire Archived 12 May 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Huge fire ripped through Titanic before it struck an iceberg, fresh evidence suggests – The Telegraph. 31 December 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016

- ^ Titanic sank due to enormous uncontrollable fire, not iceberg, claim experts – The Independent. 3 January 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2016.

- ^ Titanic Disaster: New Theory Fingers Coal Fire – Geological Society of America. 11 November 2014. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- ^ Fire Down Below - by Samuel Halpern. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Halpern & Weeks 2011, pp. 122–126.

- ^ Titanic's Guardian Angel – by Parks Stephenson. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ^ Titanic: Fire & Ice (Or What You Will) Archived 20 May 2018 at the Wayback Machine Various Authors. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

Bibliography

- Halpern, Samuel; Weeks, Charles (2011). "Description of the Damage to the Ship". In Halpern, Samuel (ed.). Report into the Loss of the SS Titanic: A Centennial Reappraisal. Stroud, UK: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-6210-3.