Tichborne case

The Tichborne case was a legal cause célèbre that fascinated Victorian Britain in the 1860s and 1870s. It concerned the claims by a man sometimes referred to as Thomas Castro or as Arthur Orton, but usually termed "the Claimant", to be the missing heir to the Tichborne baronetcy. He failed to convince the courts, was convicted of perjury and served a 14-year prison sentence.

Roger Tichborne, heir to the family's title and fortunes, was presumed to have died in a shipwreck in 1854 at age 25. His mother clung to a belief that he might have survived, and after hearing rumours that he had made his way to Australia, she advertised extensively in Australian newspapers, offering a reward for information. In 1866, a Wagga Wagga butcher known as Thomas Castro came forward claiming to be Roger Tichborne. Although his manners and bearing were unrefined, he gathered support and travelled to England. He was instantly accepted by Lady Tichborne as her son, although other family members were dismissive and sought to expose him as an impostor.

During protracted enquiries before the case went to court in 1871, details emerged suggesting that the Claimant might be Arthur Orton, a butcher's son from Wapping in London, who had gone to sea as a boy and had last been heard of in Australia. After a civil court had rejected the Claimant's case, he was charged with perjury; while awaiting trial he campaigned throughout the country to gain popular support. In 1874, a criminal court jury decided that he was not Roger Tichborne and declared him to be Arthur Orton. Before passing a sentence of 14 years, the judge condemned the behaviour of the Claimant's counsel, Edward Kenealy, who was subsequently disbarred because of his conduct.

After the trial, Kenealy instigated a popular radical reform movement, the Magna Charta Association, which championed the Claimant's cause for some years. Kenealy was elected to Parliament in 1875 as a radical independent but was not an effective parliamentarian. The movement was in decline when the Claimant was released in 1884, and he had no dealings with it. In 1895, he confessed to being Orton, only to recant almost immediately. He lived generally in poverty for the rest of his life and was destitute at the time of his death in 1898. Although most commentators have accepted the court's view that the Claimant was Orton, some analysts believe that an element of doubt remains as to his true identity and that, conceivably, he was Roger Tichborne.

Sir Roger Tichborne

Tichborne family history

The Tichbornes, of Tichborne Park near Alresford in Hampshire, were an old English Catholic family who had been prominent in the area since before the Norman Conquest. After the Reformation in the 16th century, although one of their number was hanged, drawn and quartered for complicity in the Babington Plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth I, the family in general remained loyal to the Crown, and in 1621 Benjamin Tichborne was created a baronet for services to King James I.[2]

Sir Henry Tichborne, the seventh baronet, was travelling through Verdun, France, when the Peace of Amiens broke down in May 1803, reigniting the Napoleonic Wars. As an enemy citizen, he was detained by the French authorities, who held him in captivity as a civil prisoner for some years.[4] He shared his captivity with his fourth son, James, and a nobly born Englishman, Henry Seymour of Knoyle. During his confinement, Seymour managed to conduct an affair with the daughter of the Duc de Bourbon, which produced a daughter, Henriette Felicité, born in about 1807. Years later, when Henriette had passed her 20th birthday and remained unmarried, Seymour thought his former companion James Tichborne might make a suitable husband – although James was close to his own age and was physically unprepossessing. The couple were married in August 1827; on 5 January 1829 Henriette gave birth to a son, Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne.[5]

Sir Henry had been succeeded in 1821 by his eldest son, Henry Joseph, who fathered seven daughters but no male heir. As baronetcies are inherited only by males, when Henry Joseph died in 1845 the immediate heir was his younger brother Edward, who had assumed the surname of Doughty as a condition of a legacy. Edward's only son died in childhood, so James Tichborne became next in line to the baronetcy, and after him, Roger. As the family's fortunes had been greatly augmented by the Doughty bequest, this was a considerable material prospect.[6][7]

After Roger's birth, James and Henriette had three more children: two daughters who died in infancy and a second son, Alfred, born in 1839.[8] The marriage was unhappy, and the couple spent much time apart, he in England, she in Paris with Roger. As a consequence of his upbringing, Roger spoke mainly French, and his English was heavily accented. In 1845 James decided that Roger should complete his education in England and placed him in the Jesuit boarding school Stonyhurst College, where he remained until 1848.[7] In 1849 he sat the British army entrance examinations and then took a commission in the 6th Dragoon Guards, in which he served for three years, mainly in Ireland.[9]

When on leave, Roger often stayed with his uncle Edward at Tichborne Park and became attracted to his cousin Katherine Doughty, four years his junior. Sir Edward and his wife, though they were fond of their nephew, did not consider marriage between first cousins desirable. At one point the young couple were forbidden to meet, though they continued to do so clandestinely. Feeling harassed and frustrated, Roger hoped to escape from the situation through a spell of overseas military duty; when it became clear that the regiment would remain in the British Isles, he resigned his commission.[10] On 1 March 1853 he left for a private tour of South America on board La Pauline, bound for Valparaíso in Chile.[11]

Travels and disappearance

On 19 June 1853 La Pauline reached Valparaíso, where letters informed Roger that his father had succeeded to the baronetcy, Sir Edward having died in May.[12] In all, Roger spent 10 months in South America, accompanied in the first stages by a family servant, John Moore. In the course of his inland travels he may have visited the small town of Melipilla, which lies on the route between Valparaíso and Santiago.[13] Moore, who had fallen ill, was paid off in Santiago, while Roger travelled to Peru, where he took a long hunting trip. By the end of 1853 he was back in Valparaíso, and early in the new year he began a crossing of the Andes. At the end of January, he reached Buenos Aires, where he wrote to his aunt, Lady Doughty, indicating that he was heading for Brazil, then Jamaica and finally Mexico.[14] The last positive sightings of Roger were in Rio de Janeiro, in April 1854, awaiting a sea passage to Jamaica. Although he lacked a passport he secured a berth on a ship, the Bella, which sailed for Jamaica on 20 April.[15][16]

On 24 April 1854 a capsized ship's boat bearing the name Bella was discovered off the Brazilian coast, together with some wreckage but no personnel, and the ship's loss with all hands was assumed. The Tichborne family were told in June that Roger must be presumed lost, though they retained a faint hope, fed by rumours, that another ship had picked up survivors and taken them to Australia.[15][17] Sir James Tichborne died in June 1862, at which point, if he was alive, Roger became the 11th baronet. As he was by then presumed dead, the title passed to his younger brother Alfred, whose financial recklessness rapidly brought about his near-bankruptcy.[18] Tichborne Park was vacated and leased to tenants.[19]

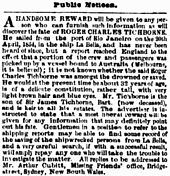

Encouraged by a clairvoyant's assurance that her elder son was alive and well, in February 1863 Roger's mother Henriette, now Lady Tichborne, began placing regular newspaper advertisements in The Times offering a reward for information about Roger Tichborne and the fate of the Bella.[18] None of these produced results; however, in May 1865 Lady Tichborne saw an advertisement placed by Arthur Cubitt of Sydney, Australia, on behalf of his "Missing Friends Agency". She wrote to him, and he agreed to place a series of notices in Australian newspapers. These gave details of the Bella's last voyage and described Roger Tichborne as "of a delicate constitution, rather tall, with very light brown hair and blue eyes". A "most liberal reward" would be given "for any information that may definitely point out his fate".[20]

Claimant appears

In Australia

In October 1865 Cubitt informed Lady Tichborne that William Gibbes, a lawyer from Wagga Wagga, had identified Roger Tichborne in the person of a bankrupt local butcher using the name Thomas Castro.[21] During his bankruptcy examination Castro had mentioned an entitlement to property in England. He had also talked of experiencing a shipwreck and was smoking a briar pipe which carried the initials "R.C.T." When challenged by Gibbes to reveal his true name, Castro had initially been reticent but eventually agreed that he was indeed the missing Roger Tichborne; henceforth he became generally known as the Claimant.[19][21]

Cubitt offered to accompany the supposed lost son back to England and wrote to Lady Tichborne requesting funds.[22][n 2] Meanwhile, Gibbes asked the Claimant to make out a will and to write to his mother. The will incorrectly gave Lady Tichborne's name as "Hannah Frances", and disposed of numerous non-existent parcels of supposed Tichborne property.[24] In the letter to his mother, the Claimant's references to his former life were vague and equivocal but were enough to convince Lady Tichborne that he was her elder son. Her willingness to accept the Claimant may have been influenced by the death of her younger son, Alfred, in February.[25]

In June 1866 the Claimant moved to Sydney, where he was able to raise money from banks on the basis of a statutory declaration that he was Roger Tichborne. The statement was later found to contain many errors, although the birthdate and parentage details were given correctly. It included a brief account of how he had arrived in Australia: he and others from the sinking Bella, he said, had been picked up by the Osprey, bound for Melbourne.[26] On arrival he had taken the name Thomas Castro from an acquaintance from Melipilla and had wandered for some years before settling in Wagga Wagga. He had married a pregnant housemaid, Mary Ann Bryant, and taken her child, a daughter, as his own; a further daughter had been born in March 1866.[25][27]

While in Sydney the Claimant encountered two former servants of the Tichborne family. One was a gardener, Michael Guilfoyle, who at first acknowledged the identity of Roger Tichborne but later changed his mind when asked to provide money to facilitate the return to England.[26] The second, Andrew Bogle, was a former slave at the Jamaican plantation of the Duke of Buckingham and Chandos who had thereafter worked for Sir Edward for many years before retiring. The elderly Bogle did not immediately recognise the Claimant, whose 189-pound (13.5 st; 86 kg) weight contrasted sharply with Roger's remembered slender build; however, Bogle quickly accepted that the Claimant was Roger, and remained convinced until the end of his life.[28] On 2 September 1866 the Claimant, having received funds from England, sailed from Sydney on board the Rakaia with his wife and children in first class, and a small retinue including Bogle and his youngest son Henry George in second class.[29][n 3] Good living in Sydney had raised his weight on departure to 210 pounds (15 st; 95 kg), and during the long voyage he added another 40 pounds (2.9 st; 18 kg).[30] After a journey involving several changes of ship, the party arrived at Tilbury on 25 December 1866.[29]

Recognition in France

After depositing his family in a London hotel, the Claimant called at Lady Tichborne's address and was told she was in Paris. He then went to Wapping in East London, where he enquired after a local family named Orton. Finding that they had left the area, he identified himself to a neighbour as a friend of Arthur Orton, who, he said, was now one of the wealthiest men in Australia. The significance of the Wapping visit would become apparent only later.[31] On 29 December the Claimant visited Alresford and stayed at the Swan Hotel, where the landlord detected a resemblance to the Tichbornes. The Claimant confided that he was the missing Sir Roger but asked that this be kept secret. He also sought information concerning the Tichborne family.[32]

Back in London, the Claimant employed a solicitor, John Holmes, who agreed to go with him to Paris to meet Lady Tichborne.[33] This meeting took place on 11 January at the Hôtel de Lille. As soon as she saw his face, Lady Tichborne accepted him. At Holmes's behest she lodged with the British Embassy a signed declaration formally testifying that the Claimant was her son. She was unmoved when Father Châtillon, Roger's childhood tutor, declared the Claimant an impostor, and she allowed Holmes to inform The Times in London that she had recognised Roger.[34] She settled an income of £1,000 a year on him,[n 4] and accompanied him to England to declare her support before the more sceptical members of the Tichborne family.[34]

Laying the groundwork, 1867–1871

Support and opposition

The Claimant quickly acquired significant supporters; the Tichborne family's solicitor Edward Hopkins accepted him, as did J. P. Lipscomb, the family's doctor. Lipscomb, after a detailed medical examination, reported that the Claimant possessed a distinctive genital malformation. It would later be suggested that Roger Tichborne had this same defect, but this could not be established beyond speculation and hearsay.[36][37] Many people were impressed by the Claimant's seeming ability to recall small details of Roger Tichborne's early life, such as the fly fishing tackle he had used. Several soldiers who had served with Roger in the Dragoons, including his former batman Thomas Carter, recognised the Claimant as Roger.[38][n 5] Other notable supporters included Lord Rivers, a landowner and sportsman, and Guildford Onslow, the Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) for Guildford who became one of the Claimant's staunchest advocates. Rohan McWilliam, in his account of the case, calls this wide degree of recognition remarkable, particularly given the Claimant's increasing physical differences from the slim Roger. By mid-June 1867 the Claimant's weight had reached almost 300 pounds (21 st; 140 kg) and would increase even more in the ensuing years.[39][n 6]

Despite Lady Tichborne's insistence that the Claimant was her son, the rest of the Tichbornes and their related families were almost unanimous in declaring him a fraud. They recognised Alfred Tichborne's infant son, Henry Alfred, as the 12th baronet. Lady Doughty, Sir Edward's widow, had initially accepted the evidence from Australia but changed her mind soon after the Claimant's arrival in England.[41] Lady Tichborne's brother Henry Seymour denounced the Claimant as false when he found that the latter neither spoke nor understood French (Roger's first language as a child) and lacked any trace of a French accent. The Claimant was unable to identify several family members and complained about attempts to catch him out by presenting him with impostors.[39][42] Vincent Gosford, a former Tichborne Park steward, was unimpressed by the Claimant, who, when asked to name the contents of a sealed package that Roger left with Gosford before his departure in 1853, said he could not remember.[43][n 7] The family believed that the Claimant had acquired from Bogle and other sources information that enabled him to demonstrate some knowledge of the family's affairs, including, for example, the locations of certain pictures in Tichborne Park.[44] Apart from Lady Tichborne, a distant cousin, Anthony John Wright Biddulph, was the only relation who accepted the Claimant as genuine;[39] however, as long as Lady Tichborne was alive and maintaining her support, the Claimant's position remained strong.[16]

On 31 July 1867 the Claimant underwent a judicial examination at the Chancery Division of the Royal Courts of Justice.[45] He testified that after his arrival in Melbourne in July 1854 he had worked for William Foster at a cattle station in Gippsland under the name of Thomas Castro. While there, he had met Arthur Orton, a fellow Englishman. After leaving Foster's employment the Claimant had subsequently wandered the country, sometimes with Orton, working in various capacities before setting up as a butcher in Wagga Wagga in 1865.[46] On the basis of this information, the Tichborne family sent an agent, John Mackenzie, to Australia to make further enquiries. Mackenzie located Foster's widow, who produced the old station records. These showed no reference to "Thomas Castro", although the employment of an "Arthur Orton" was recorded. Foster's widow also identified a photograph of the Claimant as Arthur Orton, thus providing the first direct evidence that the Claimant might in fact be Orton. In Wagga Wagga one local resident recalled the butcher Castro saying that he had learned his trade in Wapping.[47] When this information reached London, enquiries were made in Wapping by a private detective, ex-police inspector Jack Whicher,[48] and the Claimant's visit in December 1866 was revealed.[16][49]

Arthur Orton

Arthur Orton, a butcher's son born on 20 March 1834 in Wapping, had gone to sea as a boy and had been in Chile in the early 1850s.[16] Sometime in 1852 he arrived in Hobart, Tasmania, in the transport ship Middleton and later moved to mainland Australia. His employment by Foster at Gippsland terminated around 1857 with a dispute over wages.[50] Thereafter he disappears; if he was not Castro, there is no further direct evidence of Orton's existence, although strenuous efforts were made to find him. The Claimant hinted that some of his activities with Orton were of a criminal nature and that to confound the authorities they had sometimes exchanged names. Most of Orton's family failed to recognise the Claimant as their long-lost kinsman, although it was later revealed that he had paid them money.[16][47] A former sweetheart of Orton's, Mary Ann Loder, did identify the Claimant as Orton.[51]

Financial problems

Lady Tichborne died on 12 March 1868, thus depriving the Claimant of his principal advocate and his main source of income. He outraged the family by insisting on taking the position of chief mourner at her funeral mass. His lost income was rapidly replaced by a fund, set up by supporters, that provided a house near Alresford and an income of £1,400 a year[47] (equivalent to £160,000 in 2023).[52]

In September 1868, together with his legal team, the Claimant went to South America to meet face-to-face with potential witnesses in Melipilla who might confirm his identity. He disembarked at Buenos Aires, ostensibly to travel to Valparaíso overland and there rejoin his advisers who were continuing by sea. After waiting two months in Buenos Aires he caught a ship home. His explanations for this sudden retreat – poor health and the dangers from brigands – did not convince his backers, many of whom withdrew their support; Holmes resigned as his solicitor. Furthermore, on their return his advisers reported that no one in Melipilla had heard of "Tichborne", although they remembered a young English sailor called "Arturo".[53]

The Claimant was now bankrupt. In 1870 his new legal advisers launched a novel fundraising scheme: Tichborne Bonds, an issue of 1,000 debentures of £100 face value, the holders of which would be repaid with interest when the Claimant obtained his inheritance. About £40,000 was raised, though the bonds quickly traded at a considerable discount and were soon being exchanged for derisory sums.[54] The scheme allowed the Claimant to continue to meet his living and legal expenses for a while.[n 8] After a delay while the Franco-Prussian War and its aftermath prevented key witnesses from leaving Paris, the civil case that the Claimant hoped would confirm his identity finally came to court in May 1871.[56]

Civil case: Tichborne v. Lushington, 1871–1872

The case was listed in the Court of Common Pleas as Tichborne v. Lushington, in the form of an action for the ejectment of Colonel Lushington, the tenant of Tichborne Park. The real purpose was to establish the Claimant's identity as Sir Roger Tichborne and his rights to the family's estates; failure on his part would expose him as an impostor.[57] In addition to Tichborne Park's 2,290 acres (930 ha), the estates included manors, lands and farms in Hampshire, and considerable properties in London and elsewhere,[58] which altogether produced an annual income of over £20,000,[39] equivalent to about £2,350,000 in 2023.[35]

Evidence and cross-examination

The hearing, which took place within the Palace of Westminster,[n 9] began on 11 May 1871[60] before Sir William Bovill, who was Chief Justice of the Common Pleas.[61] The Claimant's legal team was led by William Ballantine and Hardinge Giffard, both highly experienced advocates.[n 10] Opposing them, acting on instructions from the bulk of the Tichborne family, were John Duke Coleridge, the Solicitor General (he was promoted to Attorney-General during the hearing),[63] and Henry Hawkins, a future High Court judge who was then at the height of his powers as a cross-examiner.[64][65] In his opening speech, Ballantine made much of Roger Tichborne's unhappy childhood, his overbearing father, his poor education and his frequently unwise choices of companions. The Claimant's experiences in an open boat following the wreck of the Bella had, said Ballantine, impaired his memories of his earlier years, which explained his uncertain recall.[59] Attempts to identify his client as Arthur Orton were, Ballantine argued, the concoctions of "irresponsible" private investigators acting for the Tichborne family.[66]

The first witnesses for the Claimant included former officers and men from Roger Tichborne's regiment, all of whom declared their belief that he was genuine.[67] Among servants and former servants of the Tichborne family called by Ballantine was John Moore, Roger's valet in South America. He testified that the Claimant had remembered many small details of their months together, including clothing worn and the name of a pet dog the pair had adopted.[68] Roger's cousin Anthony Biddulph explained that he had accepted the Claimant only after spending much time in his company.[69][70]

On 30 May Ballantine called the Claimant to the stand. During his examination-in-chief, the Claimant answered questions on Arthur Orton, whom he described as "a large-boned man with sharp features and a lengthy face slightly marked with smallpox".[71] He had lost sight of Orton between 1862 and 1865, but they had met again in Wagga Wagga, where the Claimant had discussed his inheritance.[72] Under cross-examination the Claimant was evasive when pressed for further details of his relationship with Orton, saying that he did not wish to incriminate himself. After questioning him on his visit to Wapping, Hawkins asked him directly: "Are you Arthur Orton?" to which he replied "I am not".[73] The Claimant displayed considerable ignorance when questioned about his time at Stonyhurst. He could not identify Virgil, confused Latin with Greek, and did not understand what chemistry was.[74] He caused a sensation when he declared that he had seduced Katherine Doughty and that the sealed package given to Gosford, the contents of which he earlier claimed not to recall, contained instructions to be followed in the event of her pregnancy.[75] Rohan McWilliam, in his chronicle of the affair, comments that from that point on the Tichborne family were fighting not only for their estates but for Katherine Doughty's honour.[74]

Collapse of the case

On 7 July the court adjourned for four months. When it resumed, Ballantine called more witnesses, including Bogle and Francis Baigent, a close family friend. Hawkins contended that Bogle and Baigent were feeding the Claimant with information, but in cross-examination he could not dent their belief that the Claimant was genuine. In January 1872 Coleridge began the case for the defence with a speech during which he categorised the Claimant as comparable with "the great impostors of history".[76] He intended to prove that the Claimant was Arthur Orton.[77] He had over 200 witnesses lined up,[78] but it transpired that few were required. Lord Bellew, who had known Roger Tichborne at Stonyhurst, testified that Roger had distinctive body tattoos which the Claimant did not possess.[76] On 4 March the jury notified the judge that they had heard enough and were ready to reject the Claimant's suit. Having ascertained that this decision was based on the evidence as a whole and not solely on the missing tattoos, Bovill ordered the Claimant's arrest on charges of perjury and committed him to Newgate Prison.[79][n 11]

Appeal to the public, 1872–1873

From his cell in Newgate, the Claimant vowed to resume the fight as soon as he was acquitted.[81] On 25 March 1872 he published in the Evening Standard an "Appeal to the Public", requesting financial help to meet his legal and living costs:[n 12] "I appeal to every British soul who is inspired by a love of justice and fair play, and is willing to defend the weak against the strong".[82][83] The Claimant had gained considerable popular support during the civil trial; his fight was perceived by many as symbolising the problems faced by the working class when seeking justice in the courts.[16] In the wake of his appeal, support committees were formed throughout the country. When he was bailed early in April, on sureties provided by Lord Rivers and Guildford Onslow, a large crowd cheered him as he left the Old Bailey.[83]

At a public meeting in Alresford on 14 May, Onslow reported that subscriptions to the defence fund were already pouring in and that invitations to visit and speak had been received from many towns. As the Claimant addressed meetings up and down the country, journalists following the campaign often commented on his pronounced cockney accent, suggestive of East London origins.[84] The campaign drew in some high-level supporters, among whom was George Hammond Whalley, a controversial anti-Catholic who was MP for Peterborough. He and Onslow were sometimes incautious in their speeches; after a meeting in St James's Hall, London, on 11 December 1872, each made specific charges against the Attorney General and the Government of trying to pervert the course of justice. They were fined £100 each for contempt of court.[85][n 13]

With few exceptions, the mainstream press was hostile to the Claimant's campaign. To counteract this, his supporters launched two short-lived newspapers, the Tichborne Gazette in May 1872 and the Tichborne News and Anti-Oppression Journal in June. The former was wholly devoted to the Claimant's cause and ran until Onslow's and Whalley's contempt convictions in December 1872. The Tichborne News, which concerned itself with a broader range of perceived injustices, closed after four months.[86][87]

Criminal case: Regina v. Castro, 1873–1874

Judges and counsel

The criminal case, to be heard in the Queen's Bench, was listed as Regina v. Castro, the name Castro being the last uncontested alias of the Claimant.[88] Because of its expected length, the case was scheduled as a trial at bar, a device that allowed a panel rather than one judge to hear it. The president of the panel was Sir Alexander Cockburn, the Lord Chief Justice.[89] His decision to hear this case was controversial, since during the civil case he had publicly denounced the Claimant as a perjurer and a slanderer.[90] Cockburn's co-judges were Sir John Mellor and Sir Robert Lush, experienced Queen's Bench justices.[89]

The prosecution team was largely that which had opposed the Claimant in the civil case, minus Coleridge. Hawkins led the team, his main assistants being Charles Bowen and James Mathew.[88][91] The Claimant's team was significantly weaker; he would not re-engage Ballantine and his other civil case lawyers declined to act for him again. Others refused the case, possibly because they knew they would have to present evidence concerning the seduction of Katherine Doughty.[88] The Claimant's backers eventually engaged Edward Kenealy, an Irish lawyer of acknowledged gifts but known eccentricity.[16] Kenealy had previously featured in several prominent defences, including those of the poisoner William Palmer and the leaders of the 1867 Fenian Rising.[92] He was assisted by undistinguished juniors: Patrick MacMahon, an Irish MP who was frequently absent, and the young and inexperienced Cooper Wyld.[93] Kenealy's task was made more difficult when several of his upper-class witnesses refused to appear, perhaps afraid of the ridicule they anticipated from the Crown's lawyers.[94] Other important witnesses from the civil case, including Moore, Baigent and Lipscomb, would not give evidence at the criminal trial.[95]

Trial

The trial, one of the lengthiest cases heard in an English court, began on 21 April 1873 and lasted until 28 February 1874, occupying 188 court days.[16][91] The tone was dominated by Kenealy's confrontational style; his personal attacks extended not only to witnesses but to the Bench and led to frequent clashes with Cockburn.[90] Under the legal rules that then applied to criminal cases, the Claimant, though present in court, was not allowed to testify.[96] Away from the court he revelled in his celebrity status; the American writer Mark Twain, who was then in London, attended an event at which the Claimant was present and "thought him a rather fine and stately figure". Twain observed that the company were "educated men, men moving in good society. ... It was 'Sir Roger', always 'Sir Roger' on all hands, no one withheld the title".[97]

Altogether, Hawkins called 215 witnesses, including numbers from France, Melipilla, Australia and Wapping, who testified either that the Claimant was not Roger Tichborne or that he was Arthur Orton. A handwriting expert swore that the Claimant's writing resembled Orton's but not Roger Tichborne's.[98] The entire story of rescue by the Osprey was, Hawkins asserted, a fraud. A ship of that name had arrived in Melbourne in July 1854 but did not correspond to the Claimant's description. Furthermore, the Claimant had provided the wrong name for Osprey's captain, and the names he gave for two of Osprey's crew were found to belong to members of the crew of the Middleton, the ship which had landed Orton at Hobart. No mention of a rescue had been found in Osprey's log or in the Melbourne harbourmaster's records.[99] Giving evidence on the contents of the sealed packet, Gosford revealed that it contained information regarding the disposition of certain properties, but nothing relating to Katherine Doughty's seduction or pregnancy.[100]

Kenealy's defence was that the Claimant was victim of a conspiracy which encompassed the Catholic Church, the government and the legal establishment. He frequently sought to demolish witnesses' character, as with Lord Bellew, whose reputation he destroyed by revealing details of the peer's adultery.[98] Kenealy's own witnesses included Bogle and Biddulph, who remained steadfast, but more sensational testimony came from a sailor called Jean Luie, who claimed that he had been on the Osprey during the rescue mission. Luie identified the Claimant as "Mr Rogers", one of six survivors picked up and taken to Melbourne. On investigation Luie was found to be an impostor, a former prisoner who had been in England at the time of the Bella's sinking. He was convicted of perjury and sentenced to seven years' imprisonment.[101]

Summing-up, verdict and sentence

After closing addresses from Kenealy and Hawkins, Cockburn began summing-up on 29 January 1874.[102] His speech was prefaced by a severe denunciation of Kenealy's conduct, "the longest, severest and best merited rebuke ever administered from the Bench to a member of the bar" according to the trial's chronicler John Morse.[103] The tone of the summing-up was partisan, frequently drawing the jury's attention to the Claimant's "gross and astonishing ignorance" of things he would certainly know if he were Roger Tichborne.[104] Cockburn rejected the Claimant's version of the sealed package contents and all imputations against Katherine Doughty's honour.[105][106] Of Cockburn's peroration, Morse remarked that "never was a more resolute determination manifested [by a judge] to control the result".[107] While much of the press applauded Cockburn's forthrightness, his summing-up was also criticised as "a Niagara of condemnation" rather than an impartial review.[108]

The jury retired at noon on Saturday 28 February, and returned to the court within 30 minutes.[109] Their verdict declared that the Claimant was not Roger Tichborne, that he had not seduced Katherine Doughty, and that he was indeed Arthur Orton. He was thus convicted of perjury. The jury added a condemnation of Kenealy's conduct during the trial. After the judges refused his request to address the court, the Claimant was sentenced to two consecutive terms of seven years' imprisonment.[110] Kenealy's behaviour ended his legal career; he was expelled from the Oxford circuit mess and from Gray's Inn, so that he could no longer practise.[92] On 2 December 1874 the Lord Chancellor revoked Kenealy's patent as a Queen's Counsel.[111]

Aftermath

Popular movement

The court's verdict swelled the popular tide in favour of the Claimant. He and Kenealy were hailed as heroes, the latter as a martyr who had sacrificed his legal career.[112] George Bernard Shaw, writing much later, highlighted the paradox whereby the Claimant was perceived simultaneously as a legitimate baronet and as a working-class man denied his legal rights by a ruling elite.[113][114] In April 1874 Kenealy launched a political organisation, the "Magna Charta Association", with a broad agenda that reflected some of the Chartist demands of the 1830s and 1840s.[16] In February 1875 Kenealy fought a parliamentary by-election for Stoke-upon-Trent as "The People's Candidate", and won with a resounding majority.[115] However, he failed to persuade the House of Commons to establish a royal commission into the Tichborne trial, his proposal securing only his own vote and the support of two non-voting tellers, against 433 opposed.[92][116] Thereafter, within parliament Kenealy became a generally derided figure, and most of his campaigning was conducted elsewhere.[117] In the years of the Tichborne movement's popularity a considerable market was created for souvenirs in the form of medallions, china figurines, teacloths and other memorabilia.[118] By 1880 interest in the case had declined, and in the general election of that year Kenealy was heavily defeated. He died of heart failure before polling closed in the election.[117] The Magna Charta Association continued for several more years, with dwindling support; The Englishman, the newspaper founded by Kenealy during the trial, closed down in May 1886, and there is no evidence of the Association's continuing activities after that date.[119]

Claimant's release and final years

The Claimant was released on licence on 11 October 1884 after serving 10 years.[120] He was much slimmer; a letter to Onslow dated May 1875 reports a loss of 148 pounds (10.6 st; 67 kg).[121] Throughout his imprisonment he had maintained that he was Roger Tichborne, but on release he disappointed supporters by showing no interest in the Magna Charta Association, instead signing a contract to tour with music halls and circuses.[120] The British public's interest in him had largely waned; in 1886 he went to New York but failed to inspire any enthusiasm there and ended up working as a bartender.[122]

He returned in 1887 to England, where, although not officially divorced from Mary Ann Bryant, he married a music hall singer, Lily Enever.[122] In 1895, for a fee of a few hundred pounds, he confessed in The People newspaper that he was, after all, Arthur Orton.[123] With the proceeds he opened a small tobacconist's shop in Islington; he quickly retracted the confession and insisted again that he was Roger Tichborne. His shop failed, as did other business attempts, and he died destitute, of heart disease, on 1 April 1898.[16] His funeral caused a brief revival of interest; around 5,000 people attended Paddington Cemetery for the burial in an unmarked pauper's grave. In what McWilliam calls "an act of extraordinary generosity" the Tichborne family allowed a card bearing the name "Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne" to be placed on the coffin before its interment. The name "Tichborne" was registered in the cemetery's records.[122]

Appraisal

Commentators have generally accepted the trial jury's verdict that the Claimant was Arthur Orton. However, McWilliam cites the monumental study by Douglas Woodruff (1957), in which the author posits that the Claimant could just possibly have been Roger Tichborne.[16] Woodruff's principal argument is the sheer improbability that anyone could conceive such an imposture from scratch, at such a distance, and then implement it: "[I]t was carrying effrontery beyond the bounds of sanity if Arthur Orton embarked with a wife and retinue and crossed the world, knowing that they would all be destitute if he did not succeed in convincing a woman he had never met and knew nothing about first-hand, that he was her son".[124]

In 1876, while the Claimant was serving his prison sentence, interest was briefly raised by the claims of William Cresswell, an inmate of a Sydney lunatic asylum, that he was Arthur Orton. There was circumstantial evidence that indicated some connection with Orton, and the Claimant's supporters campaigned to have Cresswell brought to England. Nothing came of this, although the question of Cresswell's possible identity remained a matter of dispute for years.[125][126] In 1884 a Sydney court found the matter undecided, and ruled that the status quo should be maintained; Cresswell stayed in the asylum.[127] Shortly before his death in 1904 he was visited by the contemporaneous Lady Tichborne, who found no physical resemblance to any member of the Tichborne family.[128]

Attempts have been made to reconcile some of the troubling uncertainties and contradictions within the case. To explain the degree of facial resemblance (which even Cockburn accepted) of the Claimant to the Tichborne family, Onslow suggested in The Englishman that Orton's mother, a woman named Mary Kent, was an illegitimate daughter of Sir Henry Tichborne, Roger Tichborne's grandfather. An alternative story has Mary Kent being seduced by James Tichborne, making Orton and Roger half-brothers.[124] Other versions have Orton and Roger as companions in crime in Australia, with Orton killing Roger and assuming his identity.[129] The Claimant's daughter by Mary Ann Bryant, Teresa Mary Agnes, maintained that her father confessed to her that he had killed Arthur Orton and thus could not disclose details of his Australian years.[130] There is no direct evidence for any of these theories.[124] Teresa continued to proclaim her identity as a Tichborne daughter, and in 1924 was imprisoned for making threats and demands for money to the family.[131]

Woodruff submits that the legal verdicts, although fair given the evidence before the courts, have not fully resolved the "great doubt" that Cockburn admitted hung over the case. Woodruff wrote in 1957: "Probably for ever, now, its key long since lost... a mystery remains".[132] A 1998 article in The Catholic Herald suggested that DNA profiling might resolve the mystery.[133] The enigma has launched numerous retellings of the story in book and film, including the short story "Tom Castro, the Implausible Imposter" from Jorge Luis Borges's Universal History of Infamy,[134] and David Yates's 1998 film The Tichborne Claimant.[135] Thus, Woodruff concludes, "the man who lost himself still walks in history, with no other name than that which the common voice of his day accorded him: the Claimant".[132][n 14]

See also

- The Fraud, a novel by Zadie Smith based on the case

References

Notes

- ^ Photographic evidence was not given weight in the courts because of the belief that such images could be manipulated. The above triptych was assembled after the conclusion of the criminal trial.[1]

- ^ Cubitt remained in Australia. He and Gibbes reportedly received rewards in the sums of £1,000 and £500, respectively, for their parts in finding the Claimant.[23]

- ^ Bogle's second son, Andrew, Jr., a successful barber and hairdresser in Sydney with eleven children, had to himself advance the funds needed to pay for his father and brother's passage to England.

- ^ £1,000 a year was a considerable sum at that time. Using the calculations of current value devised by MeasuringWorth.com, an annual income of £1,000 in 1867 equated in 2011 to £72,000 on the basis of the retail price index, and to £556,000 on the basis of average earnings.[35]

- ^ Carter, along with another former soldier, John M'Cann, was taken into the Claimant's household as a servant.[38]

- ^ Douglas Woodruff, in his study of the affair, gives the Claimant's weight in June 1868 as 344 pounds (24.6 st; 156 kg) and by summer 1870 as 378 pounds (27 st; 171 kg).[40]

- ^ At the time he was asked about the package, the Claimant did not know that Gosford had destroyed it. When he became aware that it no longer existed, he gave an account of the contents.[43]

- ^ According to Woodruff, the money lasted for 18 months; by the end of 1871 the Claimant was penniless again.[55]

- ^ The case began in the Court of Common Pleas, but was quickly moved to the larger Court of Queen's Bench because of the demand for tickets. Both these courts were situated in the Palace of Westminster.[59]

- ^ Ballantine held the now-defunct legal title of Serjeant-at-law. Giffard was the future Lord Halsbury, who would later serve as Great Britain's Lord Chancellor and founded Halsbury's Laws of England, a 20th and 21st century leading academic law commentary and an origin of Halsbury's Laws of Australia.[62]

- ^ The problem of finding a legally definitive name for the Claimant is illustrated by his arrest warrant, which referred to "Thomas Castro, alias Arthur Orton, alias Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne".[80]

- ^ Having lost the civil case, the Claimant was liable for all the defendants' legal costs as well as his own. This liability, estimated at around £80,000, had bankrupted him for the second time and left him without financial resources of any kind.[81]

- ^ The chairman of the St James's Hall meeting was G. B. Skipworth, a prominent radical lawyer. In January 1873 Skipworth was fined £500 and imprisoned for three months for repeating the charges against the judiciary.[86]

- ^ Henry Alfred, the 12th baronet, died in 1910. The baronetcy became extinct when his grandson, the 14th baronet, died in 1968.[6]

Citations

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 45, 197–198

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 5–6

- ^ "Sir A. Doughty-Tichborne". The Times: 10. 20 July 1968.

- ^ Woodruff, p. 6

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 7–8

- ^ a b Woodruff, p. 2

- ^ a b Annear, pp. 13–15

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 8

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 11–12

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 11

- ^ Woodruff, p. 24

- ^ Woodruff, p. 25

- ^ Woodruff, p. 26

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 27–28

- ^ a b Annear, pp. 38–39

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k McWilliam, Rohan (May 2010). "Tichborne claimant". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/53701. Retrieved 17 March 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) (subscription required)

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 13

- ^ a b Woodruff, pp. 32–33

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, pp. 14–15

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 37–38

- ^ a b Woodruff, pp. 38–40

- ^ Woodruff, p. 42

- ^ Annear, p. 79

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 16

- ^ a b Woodruff, pp. 45–48

- ^ a b Woodruff, pp. 52–54

- ^ Annear, pp. 5–6

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 17

- ^ a b Woodruff, pp. 55–56

- ^ Annear, pp. 80, 82

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 18–19

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 57–58

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 21

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, p. 23

- ^ a b "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1830 to present". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 23 March 2012.

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 139–140

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 199–200

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, p. 24

- ^ a b c d McWilliam 2007, pp. 25–26

- ^ Woodruff, p. 81

- ^ Woodruff, p. 74

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 78–81

- ^ a b Woodruff, pp. 90–91

- ^ Woodruff, p. 66

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 94–96

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 99–101

- ^ a b c McWilliam 2007, pp. 28–30

- ^ Annear, pp. 122–123

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 108–109

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 102–103

- ^ Woodruff, p. 114

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 7 May 2024.

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 31–32

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 33

- ^ Woodruff, p. 165

- ^ Woodruff, p. 166

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 36–37

- ^ McKinsey, William T. (May 1911). "The Tichborne Case". The Yale Law Journal. 20 (3): 563–69. doi:10.2307/785675. JSTOR 785675. (subscription required)

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, p. 43

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 171–172

- ^ "Chief justices of the common pleas (c.1200–1880)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/93045. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. Retrieved 25 March 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 40

- ^ Pugsley, David (2004). "Coleridge, John Duke". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5886. Retrieved 3 April 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Glazebrook, P. R. (2004). "Hawkins, Henry, Baron Brampton". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33770. Retrieved 1 April 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 40–42

- ^ Woodruff, p. 174

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 44

- ^ Woodruff, p. 178

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 45–47

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 180–185

- ^ Woodruff, p. 187

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 187

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 201–206

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, pp. 49–50

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 194–196

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, pp. 51–52

- ^ Woodruff, p. 213

- ^ Woodruff, p. 189

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 215–216

- ^ Annear, pp. 308–310

- ^ a b Woodruff, pp. 221–222

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 61–62

- ^ a b Woodruff, pp. 223–224

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 74

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 71, 77–78

- ^ a b Biagini and Reid (eds), pp. 46–47

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 64–66

- ^ a b c Woodruff, pp. 251–252

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, pp. 89–90

- ^ a b Lobban, Michael (2004). "Cockburn, Sir Alexander James Edmund". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/5765. Retrieved 2 April 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, p. 88

- ^ a b c Hamilton, J.A (2004). "Kenealy, Edward Vaughan Hyde". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15356. Retrieved 2 April 2012. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 254–255

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 267–268

- ^ Woodruff, p. 313

- ^ Woodruff, p. 259

- ^ Twain, pp. 74–75

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, pp. 95–97

- ^ Morse, pp. 33–35

- ^ Morse, pp. 74–75

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 317–318

- ^ Woodruff, p. 338

- ^ Morse, pp. 174–177

- ^ Morse, p. 78

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 328–329

- ^ Morse, pp. 226–327

- ^ Morse, p. 229

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 371–372

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 107

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 367–370

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 110–111

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 90

- ^ Shaw, pp. 23–24

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 113

- ^ Woodruff, pp. 401–402

- ^ "The Queen v. Castro – The Trial At Bar – Address For a Royal Commission". Hansard. 223: col. 1612. 23 April 1875.

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, pp. 167–168

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 201

- ^ McWilliam 2007, pp. 184–185

- ^ a b McWilliam 2007, pp. 183–185

- ^ Woodruff, p. 378

- ^ a b c McWilliam 2007, pp. 273–275

- ^ Annear, pp. 402–404

- ^ a b c Woodruff, pp. 452–453

- ^ McWilliam, pp. 158–159

- ^ Annear, pp. 300–301

- ^ Annear, pp. 392–398

- ^ Annear, pp. 405–406

- ^ Annear, p. 406

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 274

- ^ "Tichborne Trial Echo". The Register. Adelaide: National Library of Australia. 20 November 1924. p. 11. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ^ a b Woodruff, pp. 458–459

- ^ "The mystery of Roger Tichborne". The Catholic Herald (5841). London: 12. 1 May 1998. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013.

- ^ McWilliam 2007, p. 276

- ^ "The Tichborne Claimant (1998 film)". IMDb. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

Bibliography

- Annear, Robyn (2003). The Man Who Lost Himself: The Unbelievable Story of the Tichborne Claimant. London: Constable and Robinson. ISBN 1-84119-799-8.

- Biagini, Eugenio F.; Reid, Alastair J., eds. (1999). Currents of Radicalism: Popular Radicalism, Organised Labour and Party Politics in Britain, 1850–1914. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-39455-4.

- Borges, Jorge Luis (1935). A Universal History of Infamy. Buenos Aires: Editorial Tor. ISBN 0-525-47546-X.

- Gilbert, Michael, The Claimant, the Tichborne Case Revisited, (Constable and Company, London, 1959), by the well-known British mystery writer.

- McWilliam, Rohan (2007). The Tichborne Claimant: A Victorian Sensation. London: Hambledon Continuum. ISBN 978-1-85285-478-2.

- Morse, John Torrey (1874). Famous trials: The Tichborne claimant (and others). Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown and Company. OCLC 3701437.

- Seccombe, Thomas (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 932–933.

- Shaw, Bernard (1912). Androcles and the Lion: A Fable Play (Preface). London: Constable & Co. OCLC 697639556.

- Twain, Mark (1989). Following the Equator. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-26113-1. (First published in 1897 by The American Publishing Company, Hartford, Connecticut.)

- Woodruff, Douglas (1957). The Tichborne Claimant: A Victorian Mystery. London: Hollis & Carter. OCLC 315236894.