Pantheon, Rome

Facade of the Pantheon, with the Pantheon obelisk | |

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | Regio IX Circus Flaminius |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′55″N 12°28′36″E / 41.8986°N 12.4768°E |

| Type | Roman temple |

| History | |

| Builder | Trajan, Hadrian |

| Founded | 113–125 AD (current building) |

The Pantheon (UK: /ˈpænθiən/, US: /-ɒn/;[1] Latin: Pantheum,[nb 1] from Ancient Greek Πάνθειον (Pantheion) '[temple] of all the gods') is a former Roman temple and, since AD 609, a Catholic church (Italian: Basilica Santa Maria ad Martyres or Basilica of St. Mary and the Martyrs) in Rome, Italy. It was built on the site of an earlier temple commissioned by Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa during the reign of Augustus (27 BC – AD 14); then, after the original burnt down, the present building was ordered by the emperor Hadrian and probably dedicated c. AD 126. Its date of construction is uncertain, because Hadrian chose not to inscribe the new temple but rather to retain the inscription of Agrippa's older temple.[2]

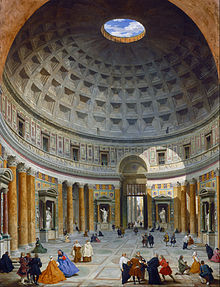

The building is round in plan, except for the portico with large granite Corinthian columns (eight in the first rank and two groups of four behind) under a pediment. A rectangular vestibule links the porch to the rotunda, which is under a coffered concrete dome, with a central opening (oculus) to the sky. Almost two thousand years after it was built, the Pantheon's dome is still the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome.[3] The height to the oculus and the diameter of the interior circle are the same, 43 metres (142 ft).[4]

It is one of the best-preserved of all Ancient Roman buildings, in large part because it has been in continuous use throughout its history. Since the 7th century, it has been a church dedicated to St. Mary and the Martyrs (Latin: Sancta Maria ad Martyres), known as "Santa Maria Rotonda".[5] The square in front of the Pantheon is called Piazza della Rotonda. The Pantheon is a state property, managed by Italy's Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism through the Polo Museale del Lazio. In 2013, it was visited by over six million people.

The Pantheon's large circular domed cella, with a conventional temple portico front, was unique in Roman architecture. Nevertheless, it became a standard exemplar when classical styles were revived, and has been copied many times by later architects.[6]

Etymology

The name "Pantheon" is from the Ancient Greek "Pantheion" (Πάνθειον) meaning "of, relating to, or common to all the gods": (pan- / "παν-" meaning "all" + theion / "θεῖον"= meaning "of or sacred to a god").[7] The simplest explanation for the name is that the Pantheon was a temple dedicated to all the gods. However, the concept of a temple dedicated to all the gods has been questioned. Ziegler tried to collect evidence of pantheons, but his list consists of simple dedications "to all the gods" or "to the Twelve Gods", which are not necessarily true pantheons in the sense of a temple housing a cult that literally worships all the gods.[8] The only definite pantheon recorded earlier than Agrippa's was at Antioch in Syria, though it is only mentioned by a sixth-century source.[9] Cassius Dio, a Roman senator who wrote in Greek, speculated that the name of the Pantheon comes either from the statues of many gods placed around this building, or from the resemblance of the dome to the heavens.[10][11] According to Adam Ziolkowski, this uncertainty strongly suggests that "Pantheon" (or Pantheum) was merely a nickname, not the formal name of the building.[12]

Godfrey and Hemsoll point out that ancient authors never refer to Hadrian's Pantheon with the word aedes, as they do with other temples, and the Severan inscription carved on the architrave uses simply "Pantheum", not "Aedes Panthei" (temple of all the gods).[13] Livy wrote that it had been decreed that temple buildings (or perhaps temple cellae) should only be dedicated to single divinities, so that it would be clear who would be offended if, for example, the building was struck by lightning, and because it was only appropriate to offer sacrifice to a specific deity (27.25.7–10).[14] Godfrey and Hemsoll maintain that the word Pantheon "need not denote a particular group of gods, or, indeed, even all the gods, since it could well have had other meanings. ... Certainly the word pantheus or pantheos, could be applicable to individual deities. ... Bearing in mind also that the Greek word θεῖος (theios) need not mean 'of a god' but could mean 'superhuman', or even 'excellent'."[13]

Since the French Revolution, when the church of Sainte-Geneviève in Paris was deconsecrated and turned into the secular monument called the Panthéon of Paris, the generic term pantheon has sometimes been applied to other buildings in which illustrious dead are honoured or buried.[1]

History

Ancient

In the aftermath of the Battle of Actium (31 BC), Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa started an impressive building program. The Pantheon was a part of the complex created by him on his own property in the Campus Martius in 29–19 BC, which included three buildings aligned from south to north: the Baths of Agrippa, the Basilica of Neptune, and the Pantheon.[15] It seems likely that the Pantheon and the Basilica of Neptune were Agrippa's sacra privata, not aedes publicae (public temples).[16] The former would help explain how the building could have so easily lost its original name and purpose (Ziolkowski contends that it was originally the Temple of Mars in Campo)[17] in such a relatively short period of time.[18]

It had long been thought that the current building was built by Agrippa, with later alterations undertaken, and this was in part because of the Latin inscription on the front of the temple[19] which reads:

- M·AGRIPPA·L·F·COS·TERTIVM·FECIT

or in full, "M[arcus] Agrippa L[ucii] f[ilius] co[n]s[ul] tertium fecit," meaning "Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, made [this building] when consul for the third time."[20] However, archaeological excavations have shown that the Pantheon of Agrippa had been completely destroyed except for the façade. Lise Hetland argues that the present construction began in 114, under Trajan, four years after it was destroyed by fire for the second time (Oros. 7.12). She reexamined Herbert Bloch's 1959 paper, which is responsible for the commonly maintained Hadrianic date, and maintains that he should not have excluded all of the Trajanic-era bricks from his brick-stamp study. Her argument is particularly interesting in light of Heilmeyer's argument that, based on stylistic evidence, Apollodorus of Damascus, Trajan's architect, was the obvious architect.[21]

The form of Agrippa's Pantheon is debated. As a result of excavations in the late 19th century, archaeologist Rodolfo Lanciani concluded that Agrippa's Pantheon was oriented so that it faced south, in contrast with the current layout that faces north, and that it had a shortened T-shaped plan with the entrance at the base of the "T". This description was widely accepted until the late 20th century. While more recent archaeological diggings have suggested that Agrippa's building might have had a circular form with a triangular porch, and it might have also faced north, much like the later rebuildings, Ziolkowski complains that their conclusions were based entirely on surmise; according to him, they did not find any new datable material, yet they attributed everything they found to the Agrippan phase, failing to account for the fact that Domitian, known for his enthusiasm for building and known to have restored the Pantheon after 80 AD, might well have been responsible for everything they found. Ziolkowski argues that Lanciani's initial assessment is still supported by all of the finds to date, including theirs; he expresses scepticism because the building they describe, "a single building composed of a huge pronaos and a circular cella of the same diameter, linked by a relatively narrow and very short passage (much thinner than the current intermediate block), has no known parallels in classical architecture and would go against everything we know of Roman design principles in general and of Augustan architecture in particular."[22]

The only passages referring to the decoration of the Agrippan Pantheon written by an eyewitness are in Pliny the Elder's Natural History. From him we know that "the capitals, too, of the pillars, which were placed by M. Agrippa in the Pantheon, are made of Syracusan bronze",[23] that "the Pantheon of Agrippa has been decorated by Diogenes of Athens, and the Caryatides, by him, which form the columns of that temple, are looked upon as masterpieces of excellence: the same, too, with the statues that are placed upon the roof,"[24] and that one of Cleopatra's pearls was cut in half so that each half "might serve as pendants for the ears of Venus, in the Pantheon at Rome".[25]

The Augustan Pantheon was destroyed along with other buildings in a fire in 80 AD. Domitian rebuilt the Pantheon, which was burnt again in 110 AD.[26]

The degree to which the decorative scheme should be credited to Hadrian's architects is uncertain. Finished by Hadrian but not claimed as one of his works, it used the text of the original inscription on the new façade (a common practice in Hadrian's rebuilding projects all over Rome; the only building on which Hadrian put his own name was the Temple to the Deified Trajan).[27] How the building was actually used is not known. The Historia Augusta says that Hadrian dedicated the Pantheon (among other buildings) in the name of the original builder (Hadr. 19.10), but the current inscription could not be a copy of the original; it does not tell us to whom Agrippa's foundation was dedicated, and, in Ziolkowski's opinion, it was highly unlikely that in 25 BC Agrippa would have presented himself as "consul tertium." On coins, the same words, "M. Agrippa L.f cos. tertium", were the ones used to refer to him after his death; consul tertium serving as "a sort of posthumous cognomen ex virtute, a remembrance of the fact that, of all the men of his generation apart from Augustus himself, he was the only one to hold the consulship thrice."[28] Whatever the cause of the alteration of the inscription might have been, the new inscription reflects the fact that there was a change in the building's purpose.[29]

Cassius Dio, a Graeco-Roman senator, consul and author of a comprehensive History of Rome, writing approximately 75 years after the Pantheon's reconstruction, mistakenly attributed the domed building to Agrippa rather than Hadrian. Dio appears to be the only near-contemporaneous writer to mention the Pantheon. Even by 200, there was uncertainty about the origin of the building and its purpose:

Agrippa finished the construction of the building called the Pantheon. It has this name, perhaps because it received among the images which decorated it the statues of many gods, including Mars and Venus; but my own opinion of the name is that, because of its vaulted roof, it resembles the heavens.

— Cassius Dio History of Rome 53.27.2

In 202, the building was repaired by the joint emperors Septimius Severus and his son Caracalla (fully Marcus Aurelius Antoninus), for which there is another, smaller inscription on the architrave of the façade, under the aforementioned larger text.[30][31] This now-barely legible inscription reads:

- IMP · CAES · L · SEPTIMIVS · SEVERVS · PIVS · PERTINAX · ARABICVS · ADIABENICVS · PARTHICVS · MAXIMVS · PONTIF · MAX · TRIB · POTEST · X · IMP · XI · COS · III · P · P · PROCOS ET

- IMP · CAES · M · AVRELIVS · ANTONINVS · PIVS · FELIX · AVG · TRIB · POTEST · V · COS · PROCOS · PANTHEVM · VETVSTATE · CORRVPTVM · CVM · OMNI · CVLTV · RESTITVERVNT

In English, this means:

- Emp[eror] Caes[ar] L[ucius] Septimius Severus Pius Pertinax, victorious in Arabia, victor of Adiabene, the greatest victor in Parthia, Pontif[ex] Max[imus], 10 times tribune, 11 times proclaimed emperor, three times consul, P[ater] P[atriae], proconsul, and

- Emp[eror] Caes[ar] M[arcus] Aurelius Antoninus Pius Felix Aug[ustus], five times tribune, consul, proconsul, have carefully restored the Pantheon ruined by age.[32]

Medieval

In 609, the Byzantine emperor Phocas gave the building to Pope Boniface IV, who converted it into a Christian church and consecrated it to St. Mary and the Martyrs on 13 May 609: "Another Pope, Boniface, asked the same [Emperor Phocas, in Constantinople] to order that in the old temple called the Pantheon, after the pagan filth was removed, a church should be made, to the holy virgin Mary and all the martyrs, so that the commemoration of the saints would take place henceforth where not gods but demons were formerly worshipped."[33] Twenty-eight cartloads of holy relics of martyrs were said to have been removed from the catacombs and placed in a porphyry basin beneath the high altar.[34] On its consecration, Boniface placed an icon of the Mother of God as 'Panagia Hodegetria' (All Holy Directress) within the new sanctuary.[35]

The building's consecration as a church saved it from the abandonment, destruction, and the worst of the spoliation that befell the majority of ancient Rome's buildings during the Early Middle Ages. However, Paul the Deacon records the spoliation of the building by the Emperor Constans II, who visited Rome in July 663:

Remaining at Rome twelve days he pulled down everything that in ancient times had been made of metal for the ornament of the city, to such an extent that he even stripped off the roof of the church [of the blessed Mary], which at one time was called the Pantheon, and had been founded in honour of all the gods and was now by the consent of the former rulers the place of all the martyrs; and he took away from there the bronze tiles and sent them with all the other ornaments to Constantinople.

Much fine external marble has been removed over the centuries – for example, capitals from some of the pilasters are in the British Museum.[36] Two columns were swallowed up in the medieval buildings that abutted the Pantheon on the east and were lost. In the early 17th century, Urban VIII Barberini tore away the bronze ceiling of the portico, and replaced the medieval campanile with the famous twin towers (often wrongly attributed to Bernini[37]) called "the ass's ears",[38] which were not removed until the late 19th century.[39] The only other loss has been the external sculptures, which adorned the pediment above Agrippa's inscription. The marble interior has largely survived, although with extensive restoration.

Renaissance

Since the Renaissance the Pantheon has been the site of several important burials. Among those buried there are the painters Raphael and Annibale Carracci, the composer Arcangelo Corelli, and the architect Baldassare Peruzzi. In the 15th century, the Pantheon was adorned with paintings: the best-known is the Annunciation by Melozzo da Forlì. Filippo Brunelleschi, among other architects, looked to the Pantheon as inspiration for their works.

Pope Urban VIII (1623 to 1644) ordered the bronze ceiling of the Pantheon's portico melted down. Most of the bronze was used to make bombards for the fortification of Castel Sant'Angelo, with the rest used by the Apostolic Camera for other works. It is also said that the bronze was used by Bernini in creating his famous baldachin above the high altar of St. Peter's Basilica, though the archaeologist Carlo Fea discovered from the Pope's accounts that about 90% of the bronze was used for the cannon, and that the bronze for the baldachin came from Venice.[41] Concerning this, an anonymous contemporary Roman satirist quipped in a pasquinade (a publicly posted poem) that quod non fecerunt barbari fecerunt Barberini ("What the barbarians did not do the Barberinis [Urban VIII's family name] did").

In 1747, the broad frieze below the dome with its false windows was "restored," but bore little resemblance to the original. In the early decades of the 20th century, a piece of the original, as far as could be reconstructed from Renaissance drawings and paintings, was recreated in one of the panels.

Modern

Two kings of Italy are buried in the Pantheon: Vittorio Emanuele II and Umberto I, as well as Umberto's Queen, Margherita. It was supposed to be the final resting place for the Monarchs of Italy of the House of Savoy, but the Monarchy was abolished in 1946 and the authorities have refused to grant burial to the former kings who died in exile (Victor Emmanuel III and Umberto II). The National Institute for the Honour Guard of the Royal Tombs of the Pantheon was originally chartered by the House of Savoy and subsequently operating with authorization of the Italian Republic, mounts as guards of honour in front of the royal tombs.[42]

The Pantheon is in use as a Catholic church, and as such, visitors are asked to keep an appropriate level of deference. Masses are celebrated there on Sundays and holy days of obligation. Weddings are also held there from time to time.

Structure

Portico

The building was originally approached by a flight of steps. Later construction raised the level of the ground leading to the portico, eliminating these steps.[5]

The pediment was decorated with relief sculpture, probably of gilded bronze. Holes marking the location of clamps that held the sculpture suggest that its design was likely an eagle within a wreath; ribbons extended from the wreath into the corners of the pediment.[43]

On the intermediate block between the portico and the rotunda, the remains of a second pediment suggests that the existing portico is much shorter than originally intended. A portico aligned with the second pediment would fit columns with shafts 50 Roman feet (14.8 metres) tall and capitals 10 Roman feet tall (3 metres), whereas the existing portico has shafts 40 Roman feet (11.9 metres) tall and capitals eight Roman feet (2.4 metres) tall.[44][45]

Mark Wilson Jones has attempted to explain the design adjustments by suggesting that, once the higher pediment had been constructed, the required 50-foot columns failed to arrive (possibly as a result of logistical difficulties).[44] The builders then had to make some awkward adjustments to fit the shorter columns and pediments. Rabun Taylor has noted that, even if the taller columns were delivered, basic construction constraints may have prevented their use.[45] Assuming that each column would first be laid on the floor next to its pediment before being pivoted upright (using something like an A-frame), there would be a space requirement of a column-length on one side of the pediment, and at least a column-length on the opposite side for the pivoting equipment and ropes. With 50-foot columns, "there was no way to sequence the erection of [the columns] without creating a hopeless snarl. The shafts were simply too long to be positioned on the floor in a workable configuration, regardless of sequence."[45] Specifically, the innermost row of columns would be blocked by the main body of the temple, and in the later stages of construction some already-erected columns would inevitably obstruct the erection of further columns.

It has also been argued that the scale of the portico was related to the urban design of the space in front of the temple.[46]

The grey granite columns that were used in the Pantheon's pronaos were quarried in Egypt at Mons Claudianus in the eastern mountains. Each was 11.9 metres (39 ft) tall, 1.5 metres (4 ft 11 in) in diameter, and 60 tonnes (59 long tons; 66 short tons) in weight.[47] These were dragged more than 100 km (62 miles) from the quarry to the river on wooden sledges. They were floated by barge down the Nile when the water level was high during the spring floods, and then transferred to vessels to cross the Mediterranean Sea to the Roman port of Ostia. There, they were transferred back onto barges and pulled up the Tiber River to Rome.[48] After being unloaded near the Mausoleum of Augustus, the site of the Pantheon was still about 700 metres away.[49] Thus, it was necessary to either drag them or to move them on rollers to the construction site.

In the walls at the back of the Pantheon's portico are two huge niches, perhaps intended for statues of Augustus Caesar and Agrippa.

The large bronze doors to the cella, measuring 4.45 metres (14.6 ft) wide by 7.53 metres (24.7 ft) high, are the oldest in Rome.[50] These were thought to be a 15th-century replacement for the original, mainly because they were deemed by contemporary architects to be too small for the door frames.[51] Later analysis of the fusion technique confirmed that these are the original Roman doors,[50] a rare example of Roman monumental bronze surviving, despite cleaning and the application of Christian motifs over the centuries.

Rotunda

The 4,535-tonne (4,463-long-ton; 4,999-short-ton) weight of the Roman concrete dome is concentrated on a ring of voussoirs 9.1 metres (30 ft) in diameter that form the oculus, while the downward thrust of the dome is carried by eight barrel vaults in the 6.4-metre-thick (21 ft) drum wall into eight piers. The thickness of the dome varies from 6.4 metres (21 ft) at the base of the dome to 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) around the oculus.[52] The materials used in the concrete of the dome also vary. At its thickest point, the aggregate is travertine, then terracotta tiles, then at the very top, tufa and pumice, both porous light stones. At the very top, where the dome would be at its weakest and vulnerable to collapse, the oculus lightens the load.[53]

No tensile test results are available on the concrete used in the Pantheon; however, Cowan discussed tests on ancient concrete from Roman ruins in Libya, which gave a compressive strength of 20 MPa (2,900 psi). An empirical relationship gives a tensile strength of 1.47 MPa (213 psi) for this specimen.[52] Finite element analysis of the structure by Mark and Hutchison[54] found a maximum tensile stress of only 0.128 MPa (18.5 psi) at the point where the dome joins the raised outer wall.[3]

The stresses in the dome were found to be substantially reduced by the use of successively less dense aggregate stones, such as small pots or pieces of pumice, in higher layers of the dome. Mark and Hutchison estimated that, if normal weight concrete had been used throughout, the stresses in the arch would have been some 80% greater. Hidden chambers engineered within the rotunda form a sophisticated structural system.[55] This reduced the weight of the roof, as did the oculus eliminating the apex.[56]

The top of the rotunda wall features a series of brick relieving arches, visible on the outside and built into the mass of the brickwork. The Pantheon is full of such devices – for example, there are relieving arches over the recesses inside – but all these arches were hidden by marble facing on the interior and possibly by stone revetment or stucco on the exterior.

The height to the oculus and the diameter of the interior circle are the same, 43.3 metres (142 ft), so the whole interior would fit exactly within a cube (or, a 43.3-m sphere could fit within the interior).[57] These dimensions make more sense when expressed in ancient Roman units of measurement: The dome spans 150 Roman feet; the oculus is 30 Roman feet in diameter; the doorway is 40 Roman feet high.[58] The Pantheon still holds the record for the world's largest unreinforced concrete dome. It is also substantially larger than earlier domes.[59] It is the only masonry dome to not require reinforcement. All other extant ancient domes were either designed with tie-rods, chains and banding or have been retrofitted with such devices to prevent collapse.[60]

Though often drawn as a free-standing building, there was a building at its rear which abutted it. While this building helped buttress the rotunda, there was no interior passage from one to the other.[61]

Interior

| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Upon entry, visitors are greeted by an enormous rounded room covered by the dome. The oculus at the top of the dome was never covered, allowing rainfall through the ceiling and onto the floor. Because of this, the interior floor is equipped with drains and has been built with an incline of about 30 centimetres (12 in) to promote water runoff.[62][63]

The interior of the dome was possibly intended to symbolize the arched vault of the heavens.[57] The oculus at the dome's apex and the entry door are the only natural sources of light in the interior. Throughout the day, light from the oculus moves around this space in a reverse sundial effect: marking time with light rather than shadow.[64] The oculus also offers cooling and ventilation; during storms, a drainage system below the floor handles rain falling through the oculus. On Pentecost, huge quantities of red rose petals are thrown through the oculus by firefighters of the Vigili del Fuoco on the roof.[65]

The dome features sunken panels (coffers), in five rings of 28. This evenly spaced layout was difficult to achieve and, it is presumed, had symbolic meaning, either numerical, geometric, or lunar.[66][67] In antiquity, the coffers may have contained bronze rosettes symbolising the starry firmament.[68]

Circles and squares form the unifying theme of the interior design. The checkerboard floor pattern contrasts with the concentric circles of square coffers in the dome. Each zone of the interior, from floor to ceiling, is subdivided according to a different scheme. As a result, the interior decorative zones do not line up. The overall effect is immediate viewer orientation according to the major axis of the building, even though the cylindrical space topped by a hemispherical dome is inherently ambiguous. This discordance has not always been appreciated, and the attic level was redone according to Neoclassical taste in the 18th century.[69]

Catholic additions

| Church of St. Mary of the Martyrs | |

|---|---|

Chiesa Santa Maria dei Martiri Sancta Maria ad Martyres | |

The tomb of Raphael | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Roman Catholic |

| Ecclesiastical or organizational status | Minor basilica, Rectory church |

| Leadership | Msgr. Daniele Micheletti |

| Year consecrated | 13 May 609 |

| Location | |

| Location | Rome, Italy |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°53′55″N 12°28′36″E / 41.8986°N 12.4768°E |

| Architecture | |

| Style | Roman |

| Completed | 126 |

| Specifications | |

| Direction of façade | North |

| Length | 84 metres (276 ft) |

| Width | 58 metres (190 ft) |

| Height (max) | 58 metres (190 ft) |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

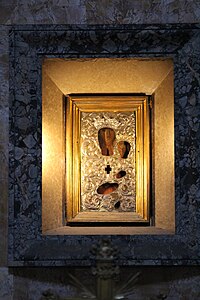

The present high altars and the apses were commissioned by Pope Clement XI (1700–1721) and designed by Alessandro Specchi. Enshrined on the apse above the high altar is a 7th-century Byzantine icon of the Virgin and Child, given by Phocas to Pope Boniface IV on the occasion of the dedication of the Pantheon for Christian worship on 13 May 609. The choir was added in 1840, and was designed by Luigi Poletti.

The first niche to the right of the entrance holds a Madonna of the Girdle and St Nicholas of Bari (1686) painted by an unknown artist. The first chapel on the right, the Chapel of the Annunciation, has a fresco of the Annunciation attributed to Melozzo da Forlì. On the left side is a canvas by Clement Maioli of St Lawrence and St Agnes (1645–1650). On the right wall is the Incredulity of St Thomas (1633) by Pietro Paolo Bonzi.

The second niche has a 15th-century fresco of the Tuscan school, depicting the Coronation of the Virgin. In the second chapel is the tomb of King Victor Emmanuel II (died 1878). It was originally dedicated to the Holy Spirit. A competition was held to decide which architect should design it. Giuseppe Sacconi participated, but lost – he would later design the tomb of Umberto I in the opposite chapel.

Manfredo Manfredi won the competition, and started work in 1885. The tomb consists of a large bronze plaque surmounted by a Roman eagle and the arms of the house of Savoy. The golden lamp above the tomb burns in honor of Victor Emmanuel III, who died in exile in 1947.

The third niche has a sculpture by Il Lorenzone of St Anne and the Blessed Virgin. In the third chapel is a 15th-century painting of the Umbrian school, The Madonna of Mercy between St Francis and St John the Baptist. It is also known as the Madonna of the Railing, because it originally hung in the niche on the left-hand side of the portico, where it was protected by a railing. It was moved to the Chapel of the Annunciation, and then to its present position sometime after 1837. The bronze epigram commemorated Pope Clement XI's restoration of the sanctuary. On the right wall is the canvas Emperor Phocas presenting the Pantheon to Pope Boniface IV (1750) by an unknown. There are three memorial plaques in the floor, one conmmemorating a Gismonda written in the vernacular. The final niche on the right side has a statue of St. Anastasius (Sant'Anastasio) (1725) by Bernardino Cametti.[70]

On the first niche to the left of the entrance is an Assumption (1638) by Andrea Camassei. The first chapel on the left, the Chapel of St Joseph in the Holy Land, is the chapel of the Confraternity of the Virtuosi al Pantheon, a confraternity of artists and musicians formed by a 16th-century canon, Desiderio da Segni, to ensure that worship was maintained in the chapel.

The first members were, among others, Antonio da Sangallo the younger, Jacopo Meneghino, Giovanni Mangone, Zuccari, Domenico Beccafumi, and Flaminio Vacca. The confraternity continued to draw members from the elite of Rome's artists and architects, and among later members we find Bernini, Cortona, Algardi, and many others. The institution still exists, and is now called the Academia Ponteficia di Belle Arti (The Pontifical Academy of Fine Arts), based in the palace of the Cancelleria. The altar in the chapel is covered with false marble. On the altar is a statue of St Joseph and the Holy Child by Vincenzo de' Rossi.

To the sides are paintings (1661) by Francesco Cozza, one of the Virtuosi: Adoration of the Shepherds on left side and Adoration of the Magi on right. The stucco relief on the left, Dream of St Joseph, is by Paolo Benaglia, and the one on the right, Rest during the flight from Egypt, is by Carlo Monaldi. On the vault are several 17th-century canvases, from left to right: Cumean Sibyl by Ludovico Gimignani; Moses by Francesco Rosa; Eternal Father by Giovanni Peruzzini; David by Luigi Garzi; and Eritrean Sibyl by Giovanni Andrea Carlone.

The second niche has a statue of St Agnes, by Vincenzo Felici. The bust on the left is a portrait of Baldassare Peruzzi, derived from a plaster portrait by Giovanni Duprè. The tomb of King Umberto I and his wife Margherita di Savoia is in the next chapel. The chapel was originally dedicated to St Michael the Archangel, and then to St. Thomas the Apostle. The present design is by Giuseppe Sacconi, completed after his death by his pupil Guido Cirilli. The tomb consists of a slab of alabaster mounted in gilded bronze. The frieze has allegorical representations of Generosity, by Eugenio Maccagnani, and Munificence, by Arnaldo Zocchi. The royal tombs are maintained by the National Institute of Honour Guards to the Royal Tombs, founded in 1878. They also organize picket guards at the tombs. The altar with the royal arms is by Cirilli.

The third niche holds the mortal remains – his Ossa et cineres, "Bones and ashes", as the inscription on the sarcophagus says – of the great artist Raphael. His fiancée, Maria Bibbiena is buried to the right of his sarcophagus; she died before they could marry. The sarcophagus was given by Pope Gregory XVI, and its inscription reads ILLE HIC EST RAPHAEL TIMUIT QUO SOSPITE VINCI / RERUM MAGNA PARENS ET MORIENTE MORI, meaning "Here lies Raphael, by whom the great mother of all things (Nature) feared to be overcome while he was living, and while he was dying, herself to die". The epigraph was written by Pietro Bembo.

The present arrangement is from 1811, designed by Antonio Muñoz. The bust of Raphael (1833) is by Giuseppe Fabris. The two plaques commemorate Maria Bibbiena and Annibale Carracci. Behind the tomb is the statue known as the Madonna del Sasso (Madonna of the Rock) so named because she rests one foot on a boulder. It was commissioned by Raphael and made by Lorenzetto in 1524.

In the Chapel of the Crucifixion, the Roman brick wall is visible in the niches. The wooden crucifix on the altar is from the 15th century. On the left wall is a Descent of the Holy Ghost (1790) by Pietro Labruzi. On the right side is the low relief Cardinal Consalvi presents to Pope Pius VII the five provinces restored to the Holy See (1824) made by the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen. The bust is a portrait of Cardinal Agostino Rivarola. The final niche on this side has a statue of St. Evasius (Sant'Evasio) (1727) by Francesco Moderati.[70]

Gallery

- Pantheon during a cloudy day

- The dome photographed with a fisheye lens in 2016

- Pantheon 2013

- Tomb of King Victor Emmanuel II, "Father of the Country"

- The icon of the Madonna which was given by Phocas to Pope Boniface IV

Cardinal deaconry

On 23 July 1725, the Pantheon was established as Cardinal-deaconry of S. Maria ad Martyres, i.e. a titular church for a cardinal-deacon. On 26 May 1929, this deaconry was suppressed to establish the Cardinal Deaconry of S. Apollinare alle Terme Neroniane-Alessandrine.[citation needed]

Influence

As the best-preserved example of an Ancient Roman monumental building, the Pantheon has been enormously influential in Western architecture from at least the Renaissance on;[71] starting with Brunelleschi's 42-metre (138 ft) dome of Santa Maria del Fiore in Florence, completed in 1436.[72]

Among the most notable versions are the church of Santa Maria Assunta (1664) in Ariccia by Gian Lorenzo Bernini, which followed his work restoring the Roman original,[73] Belle Isle House (1774) in England and Thomas Jefferson's library at the University of Virginia, The Rotunda (1817–1826).[73] Others include the Rotunda of Mosta in Malta (1833).[74] The architect Carl Ludvig Engel also took influences from the structure of the Pantheon for the Nokia Church (1837).[75] Other notable replicas, such as The Rotunda (New York) (1818), have not survived.[76]

The portico-and-dome form of the Pantheon can be detected in many buildings of the 19th and 20th centuries; numerous government and public buildings, city halls, university buildings, and public libraries echo its structure.[77] The 1824 Henriette Wegner Pavilion in Oslo's famous Frogner Park features a painted miniature copy of the Pantheon dome.[78] The Pantheon's dome was an inspiration for the Volkshalle, an assembly hall planned but never built by the Nazi German architect Albert Speer for Adolf Hitler's intended rebuilding of Berlin as "Germania".[79]

See also

- Romanian Athenaeum

- Panthéon, Paris

- Pantheon, Moscow (never built)

- Manchester Central Library

- The Rotunda (University of Virginia), United States

General:

- List of Roman domes

- History of Roman and Byzantine domes

- List of largest domes

- List of tourist attractions in Rome

Notes

- ^ Although the spelling Pantheon is standard in English, only Pantheum is found in classical Latin; see, for example, Pliny, Natural History 36.38: "Agrippas Pantheum decoravit Diogenes Atheniensis". See also Oxford Latin Dictionary, s.v. "Pantheum"; Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. "Pantheon": "post-classical Latin pantheon a temple consecrated to all the gods (6th cent.; compare classical Latin pantheum)".

Footnotes

- ^ a b "Pantheon". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. December 2008.

- ^ MacDonald 1976, pp. 12–13

- ^ a b Moore, David (1999). "The Pantheon". romanconcrete.com. Retrieved 26 September 2011.

- ^ Rasch 1985, p. 119

- ^ a b MacDonald 1976, p. 18

- ^ Summerson (1980), 38–39, 38 quoted

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ Ziegler, Konrat (1949). "Pantheion". Pauly's Real-Encyclopädie der Classischen Altertumswissenschaft: neue Bearbeitung. Vol. XVIII. Stuttgart. pp. 697–747.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Thomas, Edmund (2004). "From the Pantheon of the Gods to the Pantheon of Rome". In Richard Wrigley; Matthew Craske (eds.). Pantheons; Transformations of a Monumental Idea. Aldershot: Ashgate. p. 17. ISBN 978-0754608080.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1994). "Was Agrippa's Pantheon the Temple of Mars 'In Campo'?". Papers of the British School at Rome. 62: 265. doi:10.1017/S0068246200010084. S2CID 191523665.

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman Histories 53.27, referenced in MacDonald 1976, p. 76

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1994). "Was Agrippa's Pantheon the Temple of Mars 'In Campo'?". Papers of the British School at Rome. 62: 271. doi:10.1017/S0068246200010084. S2CID 191523665.

- ^ a b Godfrey, Paul; Hemsoll, David (1986). "The Pantheon: Temple or Rotunda?". In Martin Henig; Anthony King (eds.). Pagan Gods and Shrines of the Roman Empire (Monograph No 8 ed.). Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. p. 199.

- ^ Godfrey, Paul; Hemsoll, David (1986). "The Pantheon: Temple or Rotunda?". In Martin Henig; Anthony King (eds.). Pagan Gods and Shrines of the Roman Empire (Monograph No 8 ed.). Oxford University Committee for Archaeology. p. 198.

- ^ Dio, Cassius. "Roman History". p. 53.23.3.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1999). Lexicon topographicum urbis Romae 4. Rome: Quasar. pp. 55–56.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1994). "Was Agrippa's Pantheon the Temple of Mars 'In Campo'?". Papers of the British School at Rome. 62: 261–277. doi:10.1017/S0068246200010084. S2CID 191523665.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (1994). "Was Agrippa's Pantheon the Temple of Mars 'In Campo'?". Papers of the British School at Rome. 62: 275. doi:10.1017/S0068246200010084. S2CID 191523665.

- ^ Thomas 1997, p. 165

- ^ "Pantheon". Romereborn.virginia.edu. Archived from the original on 9 November 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Hetland, Lise (9–12 November 2006). Graßhoff, G; Heinzelmann, M; Wäfler, M (eds.). "Zur Datierung des Pantheon". The Pantheon in Rome: Contributions to the Conference. Bern.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (9–12 November 2006). Graßhoff, G; Heinzelmann, M; Wäfler, M (eds.). "What did Agrippa's Pantheon Look like? New Answers to an Old Question". The Pantheon in Rome: Contributions to the Conference. Bern: 31–34.

- ^ Pliny, The Elder. "The Natural History". p. 34.7.

- ^ Pliny, The Elder. "The Natural History". p. 36.4.

- ^ Pliny, The Elder. "The Natural History". p. 9.58.

- ^ Kleiner 2007, p. 182

- ^ Ramage & Ramage 2009, p. 236

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (9–12 November 2006). Graßhoff, G; Heinzelmann, M; Wäfler, M (eds.). "What did Agrippa's Pantheon Look like? New Answers to an Old Question". The Pantheon in Rome: Contributions to the Conference. Bern: 39.

- ^ Ziolkowski, Adam (2007). Leone; Palombi; Walker (eds.). Res Bene Gestae: Ricerche di storia urbana su Roma antica in onore di Eva Margreta Steinby. Rome: Quasar.

- ^ Luigi Piale; Mariano Vasi (1851). New Guide of Rome and the Environs According to Vasi and Nibby: Containing a Description of the Monuments, Galleries, Churches [etc.] Carefully Revised and Enlarged, with an Account of the Latest Antiquarian Researches. L. Piale. p. 272.

- ^ Giuseppe Melchiorri (1834). Paolo Badalì (ed.). "Nuova guida metodica di Roma e suoi contorni – Parte Terza ("New Methodic Guide to Rome and Its Suburbs – Third Part")". Archivio viaggiatori italiani a roma e nel lazio – Istituto Nazionale Di Studi Romani (in Italian). Tuscia University. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 3 March 2014.

- ^ Emmanuel Rodocanachi (1920). Les monuments antiques de Rome encore existants: les ponts, les murs, les voies, les aqueducs, les enceintes de Rome, les palais, les temples, les arcs (in French). Libr. Hachette. p. 192.

- ^ John the Deacon, Monumenta Germaniae Historia (1848) 7.8.20, quoted in MacDonald 1976, p. 139

- ^ Popes Boniface III–VII (archived copy) oce.catholic.com, accessed 11 April 2021

- ^ Andrew J. Ekonomou. Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes. Lexington books, Toronto, 2007

- ^ "British Museum Highlights". Archived from the original on 27 October 2015.

- ^ Mormando, Franco (2011). Bernini: His Life and His Rome. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-53851-8. Retrieved 3 January 2012.

- ^ DuTemple, Leslie A. (2003). The Pantheon. Minneapolis: Lerner Publns. p. 64. ISBN 978-0822503767. Retrieved 8 May 2011.

bernini pantheon towers.

- ^ Marder 1991, p. 275

- ^ "Another view of the interior by Panini (1735), Liechtenstein Museum, Vienna". Archived from the original on 28 September 2011.

- ^ "Pantheon, The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome". Rodolpho Lanciani. Archived from the original on 1 July 2007.

- ^ "Legislatura 14 Atto di Sindacato Ispettivo n° 4-08615". Senato della Republica (in Italian). Senate of Italy. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ MacDonald 1976, pp. 63, 141–142; Claridge 1998, p. 203

- ^ a b Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Exterior, pp. 199–206

- ^ a b c Taylor, Rabun (2003). Roman Builders, a study in architectural process. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–131. ISBN 0521803349.

- ^ MacDonald, William L. (1965). The Architecture of the Roman Empire, vol. 1: An Introductory Study. Yale University Press. pp. 111–113. ISBN 978-0300028195.

- ^ Parker, Freda. "The Pantheon – Rome – 126 AD". Monolithic. Archived from the original on 26 May 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Exterior, pp. 206–212

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Exterior, pp. 206–207

- ^ a b Cinti et al. 2007, p. 29

- ^ Claridge 1998, p. 204

- ^ a b Cowan 1977, p. 56

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, p. 187, Principles of Roman Architecture

- ^ Mark & Hutchinson 1986

- ^ MacDonald 1976, p. 33 "There are openings in it [the rotunda] here and there, at various levels, that give on to some of the many different chambers that honeycomb the rotunda structure, a honeycombing that is an integral part of a sophisticated engineering solution..."

- ^ Moore, David (February 1993). "The Riddle of Ancient Roman Concrete". S Dept. of the Interior, Bureau of Reclamation, Upper Colorado Region. www.romanconcrete.com. Retrieved 20 May 2013.

- ^ a b Roth 1992, p. 30

- ^ Claridge 1998, pp. 204–205

- ^ Lancaster 2005, pp. 44–46

- ^ Ottoni, Federica; Blasi, Carlo (4 March 2015). "Hooping as an Ancient Remedy for Conservation of Large Masonry Domes". International Journal of Architectural Heritage.

- ^ MacDonald 1976, p. 34, Wilson-Jones 2003, p. 191

- ^ "Roman Pantheon". www.rome.info. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ "Pantheon". history.com. Retrieved 7 November 2018.

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Interior, pp. 182–184

- ^ "Rain of rose petals at the Pantheon - 2024". Turismo Roma. 25 April 2024. Retrieved 2 December 2024.

- ^ Lancaster 2005, p. 46

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Interior, pp. 182–183.

- ^ De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 228. ISBN 0155037692.

- ^ Wilson-Jones 2003, The Enigma of the Pantheon: The Interior, pp. 184–197

- ^ a b Marder 1980, p. 35

- ^ MacDonald 1976, pp. 94–132

- ^ King 2000

- ^ a b Summerson (1980), 38–39

- ^ Schiavone, Michael J. (2009). Dictionary of Maltese Biographies Vol. 2 G–Z. Pietà: Pubblikazzjonijiet Indipendenza. pp. 989–990. ISBN 978-9993291329.

- ^ "Engel, Carl Ludvig (1778–1840)". National Biography of Finland. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. Oxford University Press. 1998. p. 468.

- ^ MacDonald, William Lloyd (2002). The Pantheon: Design, Meaning, and Progeny. Harvard University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0674010192.

- ^ "Historiske sommerturer: I Frognerparken". Aftenposten. Retrieved 26 May 2024.

- ^ Scheerbart, Paul (2015). "The New Life: An Architectonic Apocalypse". The City Crown. By Taut, Bruno. Mindrup, Matthew; Altenmüller-Lewis, Ulrike (eds.). New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 78. ISBN 9781317038078.

References

- Cinti, Siro; De Martino, Federico; Carandini, Andrea; De Carolis, Marco; Belardi, Giovanni (2007). Pantheon. Storia e Futuro / History and Future (in Italian). Rome, Italy: Gangemi Editore. ISBN 978-8849213010.

- Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome. Oxford Archaeological Guides. Oxford Oxfordshire: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192880039.

- Cowan, Henry (1977). The Master Builders: : A History of Structural and Environmental Design From Ancient Egypt to the Nineteenth Century. New York: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0471027405.

- Favro, Diane (2005). "Making Rome a World City". The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus. Cambridge University Press. pp. 234–263. ISBN 978-0521003933.

- Hetland, L. M. (2007). "Dating the Pantheon". Journal of Roman Archaeology. 20 (1): 95–112. doi:10.1017/S1047759400005328. ISSN 1047-7594. S2CID 162028301.

- King, Ross (2000). Brunelleschi's Dome. London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0701169036.

- Kleiner, Fred S. (2007). A History of Roman Art. Belmont: Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 978-0534638467.

- Lancaster, Lynne C. (2005). Concrete Vaulted Construction in Imperial Rome: Innovations in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521842026.

- Loewenstein, Karl (1973). The Governance of Rome. The Hague, Netherlands: Martinus Nijhof. ISBN 978-9024714582.

- MacDonald, William L. (1976). The Pantheon: Design, Meaning, and Progeny. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674010191.

- Marder, Tod A. (1980). "Specchi's High Altar for the Pantheon and the Statues by Cametti and Moderati". The Burlington Magazine. 122 (922). The Burlington Magazine Publications, Ltd.: 30–40. JSTOR 879867.

- Marder, Tod A. (1991). "Alexander VII, Bernini, and the Urban Setting of the Pantheon in the Seventeenth Century". The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 50 (3). Society of Architectural Historians: 273–292. doi:10.2307/990615. JSTOR 990615.

- Mark, R.; Hutchinson, P. (1986). "On the structure of the Pantheon". Art Bulletin. 68 (1). College Art Association: 24–34. doi:10.2307/3050861. JSTOR 3050861.

- Ramage, Nancy H.; Ramage, Andrew (2009). Roman art : Romulus to Constantine (5th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0136000976.

- Rasch, Jürgen (1985). "Die Kuppel in der römischen Architektur. Entwicklung, Formgebung, Konstruktion, Architectura". Architectura. 15: 117–139.

- Roth, Leland M. (1992). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History, And Meaning. Boulder: Westview Press. ISBN 0064384934.

- Stamper, John W. (2005). The Architecture Of Roman Temples: The Republic To The Middle Empire. The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 052181068X.

- Summerson, John (1980), The Classical Language of Architecture, 1980 edition, Thames and Hudson World of Art series, ISBN 0500201773

- Thomas, Edmund (1997). "The Architectural History of the Pantheon from Agrippa to Septimius Severus via Hadrian". Hephaistos. 15: 163–186.

- Wilson-Jones, Mark (2003). Principles of Roman Architecture. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300102024.

External links

- Official webpage from Vicariate of Rome website (archived 16 September 2015)

- "Beggar's Rome" – A self-directed virtual tour of St. Maria ad Martyres (Pantheon) and other Roman churches

- Pantheon Live Webcam, Live streaming Video of the Pantheon

- Pantheon Rome, Virtual Panorama and photo gallery

- Pantheon, article in Platner's Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome

- Pantheon Rome vs Pantheon Paris. Archived 24 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine.

- Tomás García Salgado, "The geometry of the Pantheon's vault"

- Pantheon at Great Buildings/Architecture Week website (archived 15 March 2008)

- Art & History Pantheon. Archived 2010-11-24 at the Wayback Machine.

- Summer solstice at the Pantheon (archived 15 July 2011)

- Pantheon at Structurae

- Video Introduction to the Pantheon

- Panoramic Virtual Tour inside the Pantheon Archived 11 July 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- High-resolution 360° Panoramas and Images of Pantheon|Art Atlas Archived 1 January 2022 at the Wayback Machine

- audio guide Pantheon Rome

- Lucentini, M. (2012). The Rome Guide: Step by Step through History's Greatest City. Interlink. ISBN 978-1623710088.

Pantheon, Rome travel guide from Wikivoyage

Pantheon, Rome travel guide from Wikivoyage Media related to Pantheon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pantheon at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Lupercal |

Landmarks of Rome Pantheon |

Succeeded by Porta Maggiore Basilica |