The Beautiful and Damned

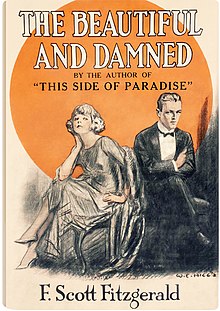

The cover of the first edition | |

| Author | F. Scott Fitzgerald |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | William E. Hill |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Tragedy |

| Published | March 4, 1922[a] |

| Publisher | Charles Scribner's Sons |

| Publication place | United States |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Preceded by | This Side of Paradise (1920) |

| Followed by | The Great Gatsby (1925) |

| Text | The Beautiful and Damned at Wikisource |

The Beautiful and Damned is a 1922 novel by American writer F. Scott Fitzgerald.[1] Set in New York City, the novel's plot follows a young artist Anthony Patch and his flapper wife Gloria Gilbert who become "wrecked on the shoals of dissipation" while partying to excess at the dawn of the hedonistic Jazz Age.[2][3] As Fitzgerald's second novel, the work focuses on the swinish behavior and glittering excesses of the American idle rich in the heyday of New York's café society.[4]

Fitzgerald modeled the characters of Anthony Patch on himself and Gloria Gilbert on his newlywed spouse Zelda Fitzgerald.[5] The novel draws circumstantially on the early years of Fitzgeralds' tempestuous marriage following the unexpected success of the author's first novel, This Side of Paradise.[6] At the time of their wedding in 1920, Fitzgerald claimed neither he nor Zelda loved each other,[7][8] and the early years of their marriage in New York City resembled a friendship.[9][10]

Having reflected upon earlier criticisms of This Side of Paradise, Fitzgerald sought to improve on the form and construction of his prose in The Beautiful and Damned and to venture into a new genre of fiction altogether.[11] He revised his second novel based on editorial suggestions from his friend Edmund Wilson and his editor Max Perkins.[12] When reviewing the manuscript, Perkins commended the conspicuous evolution of Fitzgerald's literary craftsmanship.[13]

Metropolitan Magazine serialized This Side of Paradise in late 1921, and Charles Scribner's Sons published the book in March 1922. Scribner's prepared an initial print run of 20,000 copies. Although not among the top ten best-selling novels of the year, the book sold well enough to warrant an additional printing of 50,000 copies.[14] Despite the considerable sales, critics consider the work to be among Fitzgerald's weaker novels.[15] During the final decade of his life, Fitzgerald remarked on the novel's lack of quality in a letter to his wife: "I wish The Beautiful and Damned had been a maturely written book because it was all true. We ruined ourselves—I have never honestly thought that we ruined each other."[16]

Plot summary

In 1913, Anthony Patch is a 25-year-old Harvard University alumnus recently having returned from Rome and now residing in New York City.[18] He is the presumptive heir to his dying grandfather's vast fortune. Through his friend Richard "Dick" Caramel, Anthony meets Gloria Gilbert, a beautiful flapper and "jazz baby" who is Dick's cousin.[3] Anthony begins courting her. The couple fall madly in love, with Gloria ecstatically exclaiming: "Mother says that two souls are sometimes created together—and in love before they're born."[19] After a whirlwind courtship, Anthony and Gloria marry.

For the first three years of their married life together, Anthony and Gloria vow to adhere to "the magnificent attitude of not giving a damn... for what they chose to do and what consequences it brought. Not to be sorry, not to lose one cry of regret, to live according to a clear code of honor toward each other, and to seek the moment's happiness as fervently and persistently as possible."[20] Pitted against each other's selfish attitudes, Gloria and Anthony's marital bliss evaporates. Once the couple's infatuation with each other fades, they begin to see their differences do more harm than good, as well as leaving each other with unfulfilled hopes. Over time, the disappointed couple become hedonistic and cynical libertines.

When Anthony's grandfather learns of Anthony's dissipation, he disinherits him. During World War I, Anthony serves in the American Expeditionary Forces while Gloria remains home alone until his return. While in army training, Anthony has an extramarital liaison with Dot Raycroft, a lower-class Southern woman.[21] After the Allied Powers sign an armistice with Imperial Germany in November 1918, Anthony returns to New York City and reunites with Gloria. When the struggle over the grandfather's inheritance concludes, Anthony wins his inheritance, but he has now become a hopeless alcoholic, and his wife has lost her beauty. The couple is now wealthy but morally and physically ruined.

At the end, Anthony Patch—echoing his grandfather—describes his inherited wealth as a consequence of his character rather than mere circumstance: "Only a few months before people had been urging him to give in, to submit to mediocrity... But he had known that he was justified in his way of life—and he had stuck it out staunchly... 'I showed them... It was a hard fight, but I didn't give up and I came through!"[22]

Major characters

- Anthony Patch – a Harvard alumnus and incorrigible loafer who is an heir to his grandfather's large fortune.[21] He is unambitious and unmotivated to work even as he pursues various careers.[21] He is enthralled by Gloria Gilbert's beauty and falls in love with her immediately. He is drafted into the United States Army, but the war ends before he is sent overseas.[21] Throughout the novel, he compensates for a lack of vocation with parties and ingravescent alcoholism. His expectations of future wealth make him powerless to act in the present, leaving him with empty relationships in the end.

- Gloria Gilbert – a beautiful flapper and "jazz baby" from Kansas City whom Anthony marries.[3][21] She contributes to his decline through her extravagant spending.[23][21] Self-absorbed, her personality revolves around her beauty and a belief that this quality makes her more important than everyone else. Fitzgerald loosely based the character on his wife Zelda.[24] Fitzgerald wrote a letter to his daughter Scottie delineating the differences between Gloria and Zelda: "Gloria was a much more trivial and vulgar person than your mother. I can't really say there was any resemblance except in the beauty and certain terms of expression she used, and also I naturally used many circumstantial events of our early married life. However the emphases were entirely different. We had a much better time than Anthony and Gloria had".[17]

- Richard "Dick" Caramel – an aspiring author who is one of Anthony's best friends and Gloria's cousin.[25] He is the one who brings Anthony and Gloria together.[25] During the course of the book, he publishes his novel The Demon Lover and basks in his notoriety for a good amount of time after publication.

- Joseph Bloeckman – a Jewish film producer who is in love with Gloria and hopes she will leave Anthony for him.[26] Gloria and Bloeckman had a budding relationship when Gloria met Anthony. He continues to be friends with Gloria, giving Anthony some suspicion of an extramarital affair.

- Dorothy "Dot" Raycroft – a lower-class Southern woman with whom Anthony has an affair during his army training.[27] She is a lost soul looking for someone to share her life with. She falls in love with Anthony despite learning that he is married, causes problems between Gloria and Anthony, and spurs Anthony's decline in mental health.

Writing and production

Following the success of his debut novel This Side of Paradise in March 1920, F. Scott Fitzgerald became a household name.[29] His new fame enabled him to earn much higher rates for his short stories,[30] and his increased financial prospects persuaded his fiancée Zelda Sayre to marry him as Fitzgerald could now pay for her privileged lifestyle.[b][34] Although re-engaged, Fitzgerald's feelings for Zelda ebbed to an all-time low, and he remarked to a friend, "I wouldn't care if she died, but I couldn't stand to have anybody else marry her."[35] Despite mutual reservations,[7][9] they married in a simple ceremony on April 3, 1920, at St. Patrick's Cathedral in New York City.[36] At the time of their wedding, Fitzgerald claimed neither he nor Zelda still loved each other,[7][8] and the early years of their disappointing marriage resembled a friendship.[9][10]

Living in luxury at the Biltmore Hotel in New York City,[37] the newlywed couple became national celebrities, as much for their wild behavior as for the success of Fitzgerald's novel. At the Biltmore, Scott did handstands in the lobby,[38] while Zelda slid down the hotel banisters.[39] After several weeks, the hotel asked them to leave for disturbing other guests.[38] The couple relocated two blocks to the Commodore Hotel on 42nd Street where they spent half-an-hour spinning in the revolving door.[40] Fitzgerald likened their juvenile behavior in New York City to two "small children in a great bright unexplored barn."[41] Writer Dorothy Parker first encountered the couple riding on the roof of a taxi.[42] "They did both look as though they had just stepped out of the sun", Parker recalled, "their youth was striking. Everyone wanted to meet him."[42]

Fitzgerald's ephemeral happiness mirrored the societal giddiness of the Jazz Age, a term which he popularized in his essays and stories.[43] He described the era as racing "along under its own power, served by great filling stations full of money."[44] In Fitzgerald's eyes, the era represented a morally permissive time when Americans became disillusioned with prevailing social norms and obsessed with self-gratification.[45] During this hedonistic era, alcohol—often bootleg gin[46]—fueled the Fitzgeralds' social life,[47] and the couple consumed gin-and-fruit concoctions at every outing.[38] Publicly, their alcohol intake meant little more than napping at parties, but privately it led to bitter quarrels.[47] As their quarrels worsened, the couple accused each other of marital infidelities.[48] They remarked to friends that their marriage would not last much longer.[49]

In August 1920, while in Westport, Connecticut, Fitzgerald began work on his second novel.[50] The novel had several working titles such as The Beautiful Lady Without Mercy and The Flight of the Rocket.[51] On August 12, Fitzgerald described the plot of the novel to Charles Scribner as focusing on the life of an artist who lacks creative inspiration and who, after marrying a beautiful woman, is "wrecked on the shoals of dissipation".[52] His wife Zelda interrupted Fitzgerald's writing of the novel by insisting they return to the Deep South since "she missed peaches and biscuits for breakfast."[52] After an excursion to Montgomery, Alabama, the couple returned to Westport where Fitzgerald resumed work on his novel.[52] While Fitzgerald worked on his second novel, his wife Zelda became pregnant in February 1921,[53] and the couple began planning a trip overseas to Europe.[53]

Throughout the winter and spring of 1921–22, Fitzgerald wrote and rewrote various drafts of The Beautiful and Damned.[54] He modeled the spoiled characters of Anthony Patch on himself and Gloria Patch on—in his words—the chill-minded selfishness of his wife.[5] The novel draws circumstantially on the early years of Fitzgeralds' tempestuous marriage following the meteoric success of the author's first novel This Side of Paradise.[6] Fitzgerald divided the work in pre-publication into three major parts: "The Pleasant Absurdity of Things", "The Romantic Bitterness of Things", and "The Ironic Tragedy of Things".[55] In the final book form, the novel consists of untitled "books" of three chapters each.[56]

Having digested criticisms of his debut novel This Side of Paradise, Fitzgerald sought to improve on the form and construction of his prose and to venture into a new genre of fiction altogether.[11] He revised The Beautiful and Damned based on editorial suggestions from his friend Edmund Wilson and his editor Max Perkins.[12] While reviewing the manuscript, Perkins praised the noticeable development of Fitzgerald's literary skill.[57] Fitzgerald dedicated the novel to the Anglo-Irish writer Shane Leslie, drama critic George Jean Nathan, and his editor Perkins "in appreciation of much literary help and encouragement".[58]

While finalizing the novel, Fitzgerald traveled with his wife to Europe,[53] and his agent Harold Ober sold the serialization rights for The Beautiful and Damned to Metropolitan Magazine for $7,000.[59] Metropolitan serialized the chapters from September 1921 to March 1922.[60] Shortly before the novel's publication in book form by Charles Scribner's Sons, Zelda Fitzgerald made a sketch in which she envisioned the dust jacket for her husband's novel.[28] Her sketch depicted a naked flapper sitting in a cocktail glass.[28] The publisher instead used an illustration by William E. Hill for the dust jacket.[61] On March 4, 1922, Scribner's published the book with an initial print run of approximately 20,000 copies,[a][62] and The Beautiful and Damned sold well enough to warrant additional print runs reaching 50,000 copies.[63]

Critical reception

There is a profounder truth in The Beautiful and Damned than the author perhaps intended to convey: the hero and heroine are strange creatures without purpose or method, who give themselves up to wild debaucheries and do not, from beginning to end perform a single serious act; but you somehow get the impression that, in spite of their madness, they are the most rational people in the book.... The inference is that, in such a civilization, the sanest and most creditable thing is to forget organized society and live for the jazz of the moment.

For his second novel, The Beautiful and Damned, F. Scott Fitzgerald discarded the trappings of collegiate bildungsromans as epitomized in his preceding novel This Side of Paradise and crafted an "ironical-pessimistic" [sic] novel more in the style of Thomas Hardy's literary realism.[65] Expecting more of the carefree gaiety of This Side of Paradise, the relentless pessimism of his second novel surprised several critics and prompted much comment.[66] Critic Louise Field of The New York Times asserted that The Beautiful and Damned showed Fitzgerald to be talented but too pessimistic.[67] Critic Fanny Butcher likewise lamented that Fitzgerald had traded the bubbly giddiness of This Side of Paradise for a dourness which plumbed "the bitter dregs of reality."[68]

With the publication of his sophomore effort, more perceptive critics discerned an evolution in the craftmanship of Fitzgerald's prose and structure.[69] Whereas This Side of Paradise featured unrefined prose and a chaotic structure, The Beautiful and Damned displayed a superior form and construction as well as an awakened literary consciousness.[70] Paul Rosenfeld commented that certain passages in Fitzgerald's second novel rivaled D. H. Lawrence in their artistry.[71] Remarking on Fitzgerald's improved prose and structural craftsmanship, critic H. L. Mencken wrote in his The Smart Set review, "There are a hundred signs in it of serious purpose and unquestionable skill. Even in its defects there is proof of hard striving. Fitzgerald ceases to be a wunderkind, and begins to come into his maturity".[61]

While certain critics commended the improvement in prose and structure over This Side of Paradise, others deemed The Beautiful and Damned to be less ground-breaking.[72] In contrast to the praise for This Side of Paradise as pulsing with originality,[73] Fanny Butcher deemed The Beautiful and Damned to be a more conventional effort.[74] Butcher feared that "Fitzgerald had a brilliant future ahead of him in 1920" but, "unless he does something better... it will be behind him in 1923."[74]

In contrast to Butcher's disappointment, critics John V. A. Weaver and H. L. Mencken recognized that the vast improvement in literary form and construction between Fitzgerald's first and second novels augured great prospects for his future.[75] Weaver predicted that, as Fitzgerald matured into a better writer, he would become regarded as one of the greatest authors of American literature,[76][77] and Mencken expected that Fitzgerald would significantly improve with his third work.[78]

Over a century later, many Fitzgerald scholars typically consider The Beautiful and Damned to be among Fitzgerald's weaker novels.[15] During the final decade of his life, Fitzgerald concurred about the novel's quality in a letter to his wife Zelda: "I wish The Beautiful and Damned had been a maturely written book because it was all true. We ruined ourselves—I have never honestly thought that we ruined each other."[16]

Critical analysis

Critics have analyzed The Beautiful and Damned as a morality tale, a meditation on love, money and decadence, and a social documentary. Such analyses often focus on the characters' disproportionate absorption with their past—a fixation that tends to consume them in the present. The theme of absorption in the past continues through much of Fitzgerald's subsequent works, perhaps best summarized in the final line of his 1925 novel The Great Gatsby: "So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past", which is inscribed on Fitzgerald's tombstone shared with Zelda in Maryland.[79]

According to Fitzgerald scholar James L. W. West III, The Beautiful and Damned is concerned with the question of 'vocation': 'What does one do with oneself when one has nothing to do?'[80] According to West, "Fitzgerald applied the question of vocation largely to his male characters, but he saw that women too needed meaningful roles in life."[81] Fitzgerald presents Gloria as a woman whose vocation is nothing more than to catch a husband. After her marriage to Anthony, Gloria's sole vocation is to slide into indulgence and indolence, while her husband's sole vocation is to wait for his inheritance, during which time he slides into depression and alcoholism.[82]

Publicity stunt

In April 1922, one month after The Beautiful and Damned's publication, Scott's friend, humorist Burton Rascoe, suggested that his wife Zelda Fitzgerald should write a satirical review of the book for The New-York Tribune as a publicity stunt.[83] Although Zelda had carefully proofread drafts of the novel,[84] Rascoe instructed Zelda to pretend in her tongue-in-cheek review to read the novel for the very first time and to deliberately insert a sensationalistic "rub here and there" in order to provoke a great deal of comment and boost sales.[85]

Per Rascoe's instructions, Zelda titled her satirical review "Friend Husband's Latest" and, pretending to be Scott's "greedy and self-centered" spouse,[83] Zelda joked that she hoped her husband's novel would become a commercial success as "there is the cutest cloth of gold dress for only $300 in a store on Forty-second Street".[86] In the same humorous review, Zelda wrote—partly in jest[87][88][89]—that "on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine... and, also, scraps of letters which, though considerably edited, sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald—I believe that is how he spells his name—seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home."[86]

As a consequence of Rascoe's publicity stunt, speculation emerged many decades after Zelda's death that she co-authored Scott's novel,[90] but most Fitzgerald scholars concur there is no evidence to support this claim.[91][92] Although Fitzgerald used "one page" of her diary and "scraps" of her letters with Zelda's permission for The Beautiful and Damned,[93][63] scholar Matthew J. Bruccoli states that "none of Fitzgerald's surviving manuscripts shows her hand" and Zelda never claimed to have collaborated on the novel.[63] "Fitzgerald did use bits of her diary and letters," scholar Mary Jo Tate concurs, "but she was not his collaborator."[94]

Adaptations

A film adaptation in 1922, directed by William A. Seiter, starred Kenneth Harlan as Anthony Patch and Marie Prevost as Gloria.[95] The film did well at the box office, and the critical reception was generally favorable. F. Scott Fitzgerald disliked the film, and he wrote to a friend: "It's by far the worst movie I've ever seen in my life-cheap, vulgar, ill-constructed and shoddy. We were utterly ashamed of it."[96]

References

Notes

- ^ a b Mizener 1951, p. 138, states the novel was published March 3rd, whereas Bruccoli 1981, p. 163, and Tate 1998, p. 14, state the novel was published March 4th.

- ^ During her youth, Zelda Sayre's wealthy Southern family employed domestic servants, many of whom were African-American.[31] She was unaccustomed to domestic labor or responsibilities of any kind.[32][33]

Citations

- ^ Turnbull 1962, p. 116; Mizener 1951, p. 138.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 145: Fitzgerald explained the novel's plot to Charles Scribner as centering on "an artist... with no actual creative inspiration." Over time, "he and his beautiful young wife are wrecked on the shoals of dissipation".

- ^ a b c West 2002, p. 49: "Gloria, we learn, is to be born on earth where she will be known as a 'ragtime kid,' a 'flapper', a 'jazz-baby', and a 'baby vamp'."

- ^ Mizener 1951, pp. 138–143; Milford 1970, pp. 86–89.

- ^ a b Fitzgerald 1966, pp. 355–356.

- ^ a b Tate 1998, pp. 189–190; Milford 1970, p. 88.

- ^ a b c Bruccoli 1981, p. 482: Fitzgerald wrote in 1939, "You [Zelda] submitted at the moment of our marriage when your passion for me was at as low ebb as mine for you. ... I never wanted the Zelda I married. I didn't love you again till after you became pregnant."

- ^ a b Turnbull 1962, p. 102: "Victory was sweet, though not as sweet as it would have been six months earlier before Zelda had rejected him. Fitzgerald couldn't recapture the thrill of their first love".

- ^ a b c Bruccoli 1981, p. 441: In July 1938, Fitzgerald wrote to his daughter that, "I decided to marry your mother after all, even though I knew she was spoiled and meant no good to me. I was sorry immediately I had married her but, being patient in those days, made the best of it".

- ^ a b Bruccoli 1981, p. 133: Describing his marriage to Zelda, Fitzgerald said that—aside from "long conversations" late at night—their relations lacked "a closeness" which they never "achieved in the workaday world of marriage."

- ^ a b Wilson 1952, p. 32.

- ^ a b Elias 1990, p. 254; Mizener 1951, p. 132.

- ^ Berg 1978, p. 57; Stagg 1925, p. 9; Kazin 1951, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, pp. 165–166.

- ^ a b Elias 1990, p. 266; Mizener 1951, pp. 138–143; Bruccoli 1981, pp. 155–156.

- ^ a b Bruccoli 1981, p. 155.

- ^ a b Tate 1998, pp. 189–190.

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. 131.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. 226.

- ^ a b c d e f Tate 1998, p. 189.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. 449.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 133: "Another pleasure for Zelda was spending her husband's money, at which she became adept with his encouragement."

- ^ Milford 1970, p. 88.

- ^ a b Tate 1998, p. 34.

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 23.

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 207.

- ^ a b c Bruccoli, Smith & Kerr 2003, p. 99.

- ^ Buller 2005, p. 3: "The appearance of the novel... made him a household name".

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, p. 89: "My story price had gone from $30 to $1,000. That's a small price to what was paid later in the Boom, but what it sounded like to me couldn't be exaggerated."

- ^ Wagner-Martin 2004, p. 24.

- ^ Wagner-Martin 2004, p. 24; Bruccoli 1981, pp. 194, 441.

- ^ Turnbull 1962, p. 111: "Zelda was no housekeeper. Sketchy about ordering meals, she completely ignored the laundry".

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, pp. 114, 131–132; Tate 1998, p. 82.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 101.

- ^ Turnbull 1962, p. 105; Bruccoli 1981, p. 131.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 131.

- ^ a b c Turnbull 1962, p. 110.

- ^ Turnbull 1962, p. 105.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 137.

- ^ Turnbull 1962, p. 115.

- ^ a b Milford 1970, p. 67.

- ^ Turnbull 1962, p. 224; Mizener 1951, p. 110.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, p. 18: "In any case, the Jazz Age now raced along under its own power, served by great filling stations full of money."

- ^ Fitzgerald 1945, p. 15: "[The Jazz Age represented] a whole race going hedonistic, deciding on pleasure."

- ^ Piper 1965, p. 87: "The long-winded conversations in which Anthony, Richard, and Maury discuss sex, marriage, love, education, and the meaning of life, were based on similar discussions the Fitzgeralds had enjoyed with their friends over glasses of bootleg gin during that first summer of their marriage in Westport."

- ^ a b Bruccoli 1981, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 482: Fitzgerald wrote in a letter, "You—thinking I slept with that Bankhead—making all your drunks innocent and mine calculated till even Town Topics protested."

- ^ Turnbull 1962, p. 112.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 145; Piper 1965, pp. 84, 87.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 145; Tate 1998, p. 13; Eble 1963, p. 68.

- ^ a b c Bruccoli 1981, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Bruccoli 1981, p. 149.

- ^ Milford 1970, pp. 86–89.

- ^ Elias 1990, p. 247.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. v.

- ^ Berg 1978, p. 57; Stagg 1925, p. 9; Fitzgerald 1945, p. 321.

- ^ Fitzgerald 1922, p. iv.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 150.

- ^ Tate 1998; Bruccoli 1981.

- ^ a b Tate 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 163; Tate 1998, p. 14.

- ^ a b c Bruccoli 1981, p. 166.

- ^ Kazin 1951, p. 83; Wilson 1952, p. 34.

- ^ Wilson 1952, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Field 1922; Butcher 1922, p. 109.

- ^ Field 1922.

- ^ Butcher 1922, p. 109.

- ^ Stagg 1925, p. 9; Kazin 1951, pp. 74–75; Tate 1998, p. 14; Weaver 1922, p. 3.

- ^ Stagg 1925, p. 9; Kazin 1951, pp. 74–75; Tate 1998, p. 14.

- ^ Kazin 1951, p. 75: "To be sure, a steady growth has been going on within this interesting author. The amusing insolence of his earlier manner of writing has persistently given way before a bolder, sharper stroke less personal in reference.... There are even Lawrence-like strong moments in The Beautiful and Damned."

- ^ Stagg 1925, p. 9; Hammond 1922.

- ^ Butcher 1920, p. 33.

- ^ a b Butcher 1923, p. 7.

- ^ Weaver 1922, p. 3; Mencken 1925, p. 9.

- ^ Weaver 1922, p. 3.

- ^ Bryer 1978, p. 68.

- ^ Mencken 1925, p. 9.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 218.

- ^ West 2002, p. 48.

- ^ West 2002, p. 51.

- ^ West 2002, pp. 48–51.

- ^ a b Milford 1970, p. 89.

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 86: Zelda "suggested cutting the ending..."

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 86; Bruccoli 1981, pp. 165–166; Milford 1970, p. 89.

- ^ a b Mizener 1951, pp. 123–124; Perrill 1922, p. 15.

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 14: "The review was partly a joke".

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 165: "The review is partly a joke."

- ^ Milford 1970, p. 89: "Zelda indulged in light mockery".

- ^ Green 2013.

- ^ Bruccoli 1981, p. 166: "None of Fitzgerald's surviving manuscripts shows her hand, though Zelda's manuscripts bear his revision.... She was never his collaborator."

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 86: "Fitzgerald did use bits of her diary and letters... But she was not his collaborator."

- ^ Meyers 1994, p. 88: Zelda "revealed, for the first time, that Scott — with her permission — had absorbed bits of her writing into his novel..."

- ^ Tate 1998, p. 86.

- ^ The New York Times 1922.

- ^ Tate 2007, p. 32; Ankerich 2010, p. 287.

Works cited

- Ankerich, Michael G. (2010). Dangerous Curves Atop Hollywood Heels: The Lives, Careers, and Misfortunes of 14 Hard-Luck Girls of the Silent Screen. Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-59393-605-1 – via Google Books.

- Berg, A. Scott (1978). Max Perkins: Editor of Genius. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-82719-7 – via Internet Archive.

- Buller, Richard (2005). "F. Scott Fitzgerald, Lois Moran, and the Mystery of Mariposa Street". The F. Scott Fitzgerald Review. 4. University Park, Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press: 3–19. doi:10.1111/j.1755-6333.2005.tb00013.x. JSTOR 41583088. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- Butcher, Fanny (July 21, 1923). "Fitzgerald and Leacock Write Two Funny Books". The Chicago Tribune (Saturday ed.). Chicago, Illinois. p. 7. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- —————— (June 13, 1920). "Tabloid Book Review". The Chicago Tribune (Sunday ed.). Chicago, Illinois. p. 33. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- —————— (March 5, 1922). "Tabloid Book Review". The Chicago Tribune (Sunday ed.). Chicago, Illinois. p. 109. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Bruccoli, Matthew J. (1981). Some Sort of Epic Grandeur: The Life of F. Scott Fitzgerald (1st ed.). New York and London: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-183242-0 – via Internet Archive.

- ——————; Smith, Scottie Fitzgerald; Kerr, Joan P., eds. (2003) [1974]. The Romantic Egoists: A Pictorial Autobiography from the Scrapbooks and Albums of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina Press. p. 99. ISBN 1-57003-529-6 – via Google Books.

- Bryer, Jackson R., ed. (1978). F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Critical Reception. Burt Franklin & Co. ISBN 0-89102-111-6. LCCN 78-8268 – via Internet Archive.

- Eble, Kenneth E. (1963). F. Scott Fitzgerald. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers. LCCN 63-10953 – via Internet Archive.

- Elias, Amy J. (Spring 1990). "The Composition and Revision of Fitzgerald's 'The Beautiful and Damned'". The Princeton University Library Chronicle. 51 (3). Princeton, New Jersey: 245–66. doi:10.2307/26403800. JSTOR 26403800.

- Field, Louise (March 5, 1922). "Latest Works of Fiction". The New York Times (Sunday ed.). New York City. Retrieved May 1, 2022.

- Fitzgerald, F. Scott (1922). The Beautiful and Damned. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons – via Internet Archive.

- ———————— (1945). Wilson, Edmund (ed.). The Crack-Up. New York: New Directions. ISBN 0-8112-0051-5 – via Internet Archive.

- ———————— (July 1966) [January 1940]. Turnbull, Andrew (ed.). The Letters of F. Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons – via Internet Archive.

- Green, Penelope (April 19, 2013). "Beautiful and Damned". The New York Times (Friday ed.). New York City. Retrieved August 18, 2021.

- Hammond, Percy (May 5, 1922). "Books". The New York Tribune (Friday ed.). New York City. p. 10. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Kazin, Alfred, ed. (1951). F. Scott Fitzgerald: The Man and His Work (1st ed.). New York City: World Publishing Company – via Internet Archive.

- Mencken, H. L. (May 2, 1925). "Fitzgerald, the Stylist, Challenges Fitzgerald, the Social Historian". The Evening Sun (Saturday ed.). Baltimore, Maryland. p. 9. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Milford, Nancy (1970). Zelda: A Biography. New York: Harper & Row. LCCN 66-20742 – via Internet Archive.

- Mizener, Arthur (1951). The Far Side of Paradise: A Biography of F. Scott Fitzgerald. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin – via Internet Archive.

- Meyers, Jeffrey (1994). Scott Fitzgerald: A Biography. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 0-06-019036-1 – via Internet Archive.

- Perrill, Penelope (April 9, 1922). "Paris Guide Book Now Very Much Sought For". Dayton Daily News (Sunday ed.). Dayton, Ohio. p. 15. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Piper, Henry Dan (1965). F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Critical Portrait. New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. LCCN 65-14435 – via Internet Archive.

- Stagg, Hunter (April 18, 1925). "Scott Fitzgerald's Latest Novel is Heralded As His Best". The Evening Sun (Saturday ed.). Baltimore, Maryland. p. 9. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- Tate, Mary Jo (2007). Critical Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Literary Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-0845-2 – via Google Books.

- ————— (1998) [1997]. F. Scott Fitzgerald A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File. ISBN 0-8160-3150-9 – via Internet Archive.

- "The Screen: A Gay Cruze". The New York Times (Monday ed.). New York City. December 11, 1922. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- Turnbull, Andrew (1962) [1954]. Scott Fitzgerald. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. LCCN 62-9315. Retrieved May 1, 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Wagner-Martin, Linda (Summer 2004). "Zelda Sayre, Belle". Southern Cultures. 10 (2). Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press: 19–49. doi:10.1353/scu.2004.0029. JSTOR 26390953. S2CID 143270051. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- Weaver, John V. A. (March 4, 1922). "Better Than 'This Side of Paradise'". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Saturday ed.). Brooklyn, New York. p. 3. Retrieved December 8, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- West, James L. W. III (2002). "The Question of Vocation in This Side of Paradise and The Beautiful and Damned". In Prigozy, Ruth (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to F. Scott Fitzgerald. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 48–56. ISBN 0-521-62447-9 – via Google Books.

- Wilson, Edmund (1952). The Shores of Light: A Literary Chronicle of the Twenties and Thirties. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Young – via Internet Archive.

External links

- The Beautiful and Damned at Standard Ebooks

- The Beautiful and Damned at Project Gutenberg

- The Beautiful and Damned at Internet Archive

The Beautiful and Damned public domain audiobook at LibriVox

The Beautiful and Damned public domain audiobook at LibriVox