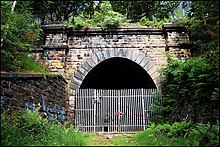

Thackley Tunnel

Thackley Tunnel is on the Airedale line between Leeds and Shipley on the lines to Bradford and Skipton.

Completed in 1846[1] and opened on 30 June, the tunnel is approximately 1,300 yards (1,200 m) long through Thackley Hill. The contractor was James Bray, an iron and brass founder from Leeds who later contracted the construction of the Bramhope Tunnel on the Leeds to Thirsk main line.[2]

As built, the single tunnel bore contained a pair of lines. In 1900, the railway was increased to four tracks, with two lines in a second tunnel. One tunnel carried the fast lines from Leeds and the other the slow lines. In 1968, the southern tunnel was closed, coinciding with the closure of the Great Northern Branch Line from Shipley to Laisterdyke via Idle and Thackley. The northern tunnel is in use. The disused tunnel is periodically maintained.

History

Construction

In 1830, proposals for a railway between Leeds and Bradford appeared before Parliament; according to author Graeme Bickerdike, they were stimulated by the burgeoning wool trade in Bradford.[3] The 9.5 miles (15.3 km) direct route posed difficulties particularly with steep gradients; one towards the western section of the line where a stationary steam engine could have had to have been used to assist trains in the ascent of a 1:30 incline. As a result of rising cost estimates, backers withdrew, leading to the failure of the Bill.[3] Nine years later, in 1839, a revised scheme was put forward, but failed to secure enough financing and was shelved.[3]

Four years later the project gained the attention of George Hudson, who became known as 'The Railway King'. Hudson's intervention played a critical role when difficulties were encountered in raising capital, Hudson offered a guaranteed return of 7.5% to prospective investors, leading to a surge in demand.[3] Robert Stephenson was consulted from an early stage and surveyed a new route along the Aire Valley to enter Bradford from the north.[3]

Stephenson's route included a 1,364 yards (1,247 m) tunnel through Thackley Hill.[3] While some opposed Stephenson's route on the grounds that it was about four miles longer than the direct route, Stephenson defended his decision. He explained to the parliamentary committee that the revised line's ruling gradient of 1:200 would be more suited to the low-powered locomotives available and journeys would be quicker and cheaper than by the direct route.[3]

In July 1844, the project received royal assent, clearing the way for construction to proceed. Staking out of the line got underway. At Thackley Hill seven shafts which reached depths of up to 252 feet (77 m) were started under the direction of engineer Francis Mortimer Young. A condensing steam engine, generating up to 25HP, was installed for lowering men and equipment into the shafts and raised spoil. In January 1845, a £68,000 contract for work in the tunnel was awarded to Messrs Nowell & Hattersley.[3]

Conditions in the tunnel were extremely challenging and worsened by rudimentary working practices and lack of safety measures.[3] Construction was near-continuous, working around-the-clock in eight-hour shifts for six days a week, breaking only on Sundays. Accidents were commonplace and deaths were a frequent occurrence and it was commonplace to attribute incidents to personal error.[3] The workforce was praised by Hudson, who spoke of their energy and spirit during a celebratory meal marking the tunnel's completion after sixteen months. On 30 June 1846, the line, now known as the Airedale line was opened to great fanfare and public spectacle and a special train departing from Leeds carrying shareholders and other key figures ran in the early afternoon.[3]

Operations

Thackley Tunnel was 1,496 yards (1,368 m), 132 yards (121 m) longer than planned.[3] Five of the shafts were retained for ventilation shafts. At least three people died in the tunnel in the 1800s and derailments and floods sporadically occurred.[3]

In July 1897, increasing levels of traffic using the line led to Midland Railway deciding that a second bore was needed.[3] Royal assent was granted to the 'Thackley Widening Act' in 1898 and contractor Thomas Oliver & Sons and engineer J. A. McDonald commenced work. On 12 January 1900 there was a fatal accident when two of the railway workers, Michael Doughty and William Wilson were severely injured in an explosion, and the 43 year old Wilson died of his injuries.[4] On 27 January 1901, the second tunnel bore was officially opened to traffic and the line increased to four tracks, two in the second tunnel.[3]

In 1968, as a result of the Beeching cuts, the original tunnel was closed and traffic rerouted through the second tunnel.[3] The first tunnel is still maintained by Network Rail's asset management regime. In April 1985, a bulge was detected at the haunch closest to the live tunnel; steps to address it included installing steel ribs to brace the area and additional monitoring.[3] During the 1980s, the closed tunnel was backfilled with spoil to prevent further distortion of the tunnel's lining.[1]

In 1992, a pair of block walls were built in the first tunnel, an 83 yards (76 m) section of tunnel between them was grouted, as was with No. 3 shaft, to prevent further deterioration.[3] The work has precluded further use of the first tunnel as there is no provision for through-access. In 2013, more distortions were detected in the roof of the first bore generating concerns that consequential defects may emerge in the operational bore which would be difficult to remediate because of overhead line equipment.[3] More infilling using lightweight foam concrete took place over 67 yards (61 m) in mid-2016 to prevent the tunnel lining failing.[3]

References

- ^ a b "Thackley Old Tunnel". www.forgottenrelics.co.uk. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Sunderland, Cllr Philip. "Bramhope Tunnel – The Facts". Bramhope & Carlton Parish Council. Archived from the original on 27 April 2009. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t "End of the Line". Rail Engineer. 1 February 2017.

- ^ "Fatal Accident". The Times. 13 January 1900.