Tea and Sympathy (film)

| Tea and Sympathy | |

|---|---|

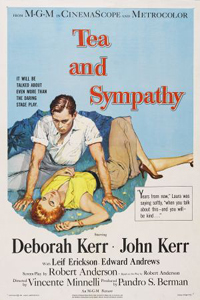

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Vincente Minnelli |

| Written by | Robert Anderson |

| Based on | Tea and Sympathy by Robert Anderson |

| Produced by | Pandro S. Berman |

| Starring | Deborah Kerr John Kerr Leif Erickson Edward Andrews |

| Cinematography | John Alton |

| Edited by | Ferris Webster |

| Music by | Adolph Deutsch |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Loew's Inc. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 122 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,737,000[1] |

| Box office | $3,445,000[1] |

Tea and Sympathy is a 1956 American drama film and an adaptation of Robert Anderson's 1953 stage play of the same name directed by Vincente Minnelli and produced by Pandro S. Berman for MGM in Metrocolor. The music score was by Adolph Deutsch and the cinematography by John Alton. Deborah Kerr, John Kerr and Leif Erickson reprised their original Broadway roles. Edward Andrews, Darryl Hickman, Norma Crane, Tom Laughlin, and Dean Jones were featured in supporting roles.

Plot

Seventeen-year-old Tom Robinson Lee (John Kerr), a new senior at a boy's prep school, finds himself at odds with the machismo culture of his class in which the other boys love sports, roughhouse, fantasize about girls, and worship their coach, Bill Reynolds (Leif Erickson). Tom prefers classical music, reads Candida, goes to the theater, and generally seems to be more at ease in the company of women.

The other boys torment Tom for his "unmanly" qualities and call him "sister boy," and he is treated unfeelingly by his father, Herb Lee (Edward Andrews), who believes a man should be manly and that his son should fit in with the other boys. Only Al (Darryl Hickman), his roommate, treats Tom with any decency, perceiving that being different is not the same as being unmasculine. This growing tension is observed by Laura Reynolds (Deborah Kerr), wife of the coach. The Reynoldses are also Tom's and Al's house master and mistress. Laura tries to build a connection with the young man, often inviting him alone to tea, and eventually falls in love with him, in part because of his many similarities to her first husband, John, who was killed in World War II.

The situation escalates when Tom is goaded into visiting the local prostitute, Ellie (Norma Crane), to dispel suspicions about his sexuality, but things go badly. Her mockery and derision at his naïveté causes him to attempt suicide in the woman's kitchen. His father arrives from the city to meet with the dean about Tom's impending expulsion, having been alerted to Tom's intentions by a classmate. Assuming his son's success, he boasts of his son's sexual triumph and time-honored leap into manhood until the Reynoldses inform him otherwise. Laura goes in search of Tom and finds him where he often goes to ruminate, near the golf course's sixth tee. She tries to comfort him, counseling that he will have a wife and family some day, but he is inconsolable. She starts to leave, then returns and takes his hand, they kiss, and she says, "Years from now, when you talk about this, and you will, be kind."

Ten years into the future the adult Tom, now a successful married writer, returns to his prep school. The final scene shows Tom visiting his old coach and house master to ask after Laura. Bill tells him that he last heard she is out west somewhere but he has a note from Laura to Tom, which she enclosed in her last letter to Bill. Tom opens it outside and learns that she wrote it after reading his published novel, derived from his time at the school and their relationship. After their moment of passion, she tells Tom, she had no choice but to leave Bill, and, as Tom wrote in his book, "the wife always kept her affection for the boy."

Cast

- Deborah Kerr as Laura Reynolds

- John Kerr as Tom Robinson Lee

- Leif Erickson as Bill Reynolds

- Edward Andrews as Herb Lee

- Darryl Hickman as Al

- Norma Crane as Ellie Martin

- Dean Jones as Ollie

- Jacqueline deWit as Lilly Sears

- Tom Laughlin as Ralph

- Ralph Votrian as Steve

- Steven Terrell as Phil

- Kip King as Ted

- Jimmy Hayes as Henry

- Dick Tyler as Roger

- Don Burnett as Vic

Production

Robert Anderson, the author of the play, was also the screenwriter of the film. Due to the Motion Picture Production Code, homosexuality is not mentioned in the film version.[2] In 1956, Bob Thomas of the Associated Press wrote that "many said [the play] could never be made into a movie."[3] Deborah Kerr, the leading actress, said that the screenplay "contains all the best elements of the play. After all, the play was about the persecution of a minority, wasn't it? That still remains the theme of the film."[3] In the film, the story's climax is written as transpiring in a "sylvan glade", while in the original play the scene takes place in the dormitory room of the student.[3]

Reception

Bosley Crowther of The New York Times gave the film a positive review and felt the movie was faithful to the play despite obvious Motion Picture Production Code alterations. However, Crowther felt the film's addition of a post-script featuring "an apologetic letter from the 'fallen woman' " was "preachy ... prudish and unnecessary", and recommended that cinemagoers leave after the line "Years from now, when you talk about this—and you will—be kind."[4]

Deborah Kerr said in regard to the screenplay that "I think Robert Anderson has done a fine job."[3]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2002: AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions – Nominated[5]

- 2005: AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes:

- Laura Reynolds: "Years from now, when you talk about this -- and you will -- be kind." – Nominated[6]

Box office

According to MGM records, the film earned $2,145,000 in the U.S.. and Canada and $1.3 million in other markets, resulting in a loss of $220,000.[1]

See also

Gerstner, David. "The Production and Display of the Closet: Making Minnelli's Tea and Sympathy." Film Quarterly 50.3 (Spring 1997): 13–26.

References

- ^ a b c The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- ^ Koresky, Michael (2019-01-16). "Queer & Now & Then: 1956". Film Comment.

- ^ a b c d Thomas, Bob. "Deborah Kerr Signs For Unusual Role." Associated Press at the Milwaukee Sentinel. May 17, 1956. Part 2, pg. 15.

- ^ Crowther, Bosley (1956-09-28). "Screen: 'Tea and Sympathy' Arrives.; Stars of Stage Play Re-Enact Roles Supersonic Drama". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees - 400 Nominated Films" (PDF). American Film Institute. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2011.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Movie Quotes Nominees - 400 Quotes" (PDF). American Film Institute. p. 89. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 March 2011.