Talk:Rhoticity in English

| This It is of interest to the following WikiProjects: | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||

"Weakened"

It seems clear to me that the "clarification needed" tag added in this edit by Wolfdog was about the word "weakened", which is phonetically vague. As in this edit summary, it is probably best for it to be next to the same statement in the body of the article rather than in the intro. — Eru·tuon 19:45, 26 June 2017 (UTC)

- I'm more interested in getting to the bottom of what in the world the phrase means. The full phrase is written as "weakened but still universally present". Wolfdog (talk) 00:04, 27 June 2017 (UTC)

- @Erutuon: Can you explain what the sentence means?, because I too may be having difficulty understanding it.LakeKayak (talk) 22:18, 27 June 2017 (UTC)

- @LakeKayak: Do you mean the sentence about /r/ being weakened? I'm not sure what it means exactly. — Eru·tuon 22:44, 27 June 2017 (UTC)

- I did mean that sentence. And for that reason, it seems the clarification needed tag was instated in the lead, because the sentence that needed to be clarified was in the lead.LakeKayak (talk) 22:47, 27 June 2017 (UTC)

- Did any of you bother to actually check the cited source itself? Its wording seemed eminently clear to me. Here is a relevant excerpt: "We can conclude that in less formal speech /r/-loss began sporadically in the fifteenth century; that in the seventeenth it had weakened postvocalic allophones; and that in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries it was generally still pronounced in all positions, but by the 1740s to 1770s was on the way to deletion, perhaps especially after low vowels." The passage dealing with this issue is mostly on pages 114-115. White Whirlwind 咨 23:48, 27 June 2017 (UTC)

- @White whirlwind: I should admit that I didn't initially see the source. I was looking in the wrong spot. Anyway, here to check that I understand you clearly, it sounds like "weakened" is used to mean that the /r/ became rather faint. Is this analysis accurate?LakeKayak (talk) 01:49, 28 June 2017 (UTC)

- @LakeKayak: yes, it seems to have lenited over time. White Whirlwind 咨 04:21, 28 June 2017 (UTC)

- Thanks very much! Wolfdog (talk) 13:12, 28 June 2017 (UTC)

- @LakeKayak: yes, it seems to have lenited over time. White Whirlwind 咨 04:21, 28 June 2017 (UTC)

- @White whirlwind: I haven't seen the source, but it doesn't really make it clear what the word "weakened" means phonetically. Change from a trill to an approximant, or to some kind of semivowel? I gather it means lenition, but that's not particularly helpful, because there are many kinds of lenition. — Eru·tuon 18:50, 28 June 2017 (UTC)

- @Erutuon: the source is quite clear that there's not enough data to make that fine of a distinction in this case. It basically says /r/ was originally a consonant (either trill or approximant or otherwise, we can't be sure), and it gradually lenited to nothing and/or a lengthened vowel. Go read the source yourself. In any case, we're being unnecessarily pedantic here. White Whirlwind 咨 20:48, 28 June 2017 (UTC)

- @White whirlwind: I should admit that I didn't initially see the source. I was looking in the wrong spot. Anyway, here to check that I understand you clearly, it sounds like "weakened" is used to mean that the /r/ became rather faint. Is this analysis accurate?LakeKayak (talk) 01:49, 28 June 2017 (UTC)

- Did any of you bother to actually check the cited source itself? Its wording seemed eminently clear to me. Here is a relevant excerpt: "We can conclude that in less formal speech /r/-loss began sporadically in the fifteenth century; that in the seventeenth it had weakened postvocalic allophones; and that in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries it was generally still pronounced in all positions, but by the 1740s to 1770s was on the way to deletion, perhaps especially after low vowels." The passage dealing with this issue is mostly on pages 114-115. White Whirlwind 咨 23:48, 27 June 2017 (UTC)

- I did mean that sentence. And for that reason, it seems the clarification needed tag was instated in the lead, because the sentence that needed to be clarified was in the lead.LakeKayak (talk) 22:47, 27 June 2017 (UTC)

- @LakeKayak: Do you mean the sentence about /r/ being weakened? I'm not sure what it means exactly. — Eru·tuon 22:44, 27 June 2017 (UTC)

- @Erutuon: Can you explain what the sentence means?, because I too may be having difficulty understanding it.LakeKayak (talk) 22:18, 27 June 2017 (UTC)

Dates

In the lead, it seems potentially confusing to me to simultaneously have "1700s" referring to 1701-1799 and "1740s" referring to 1740-1749. One refers to a century, the other to a decade. The other option is to use "18th century" but "1740s". I don't like the mismatch there either. — Eru·tuon 20:09, 28 June 2017 (UTC)

- It took me a while just to even figure out what your concern was. How often is "1700s" used to mean 1700s (decade)? Other than the Wikipedia term, I've never in my life heard anyone talk about the "1700s" to mean the first decade of the 18th century. Anyway, I'd certainly prefer that potential confusion when compared to the other mismatch approach you mention. Just my personal opinion though. Wolfdog (talk) 01:02, 29 June 2017 (UTC)

- I find this discussion strange and more than a bit surreal. I can't fathom why anyone over the age of 10 (unless perhaps if they were not a native English speaker) would see incongruity in, say, "18th century" and "1740s". This is common and standard in all modern English prose, including in the main source for the "History" subsection of the article at hand. Additionally, I have never seen "the 1700s" used to refer to 1700–1709; the term would be something like "the first decade of the 18th century". The change from "18th century" to "1700s" makes the prose smack of a juvenile editor copying from the Simple English Wikipedia, and should have been reverted (I will do it now). In any case, it's also flat-out wrong, since "the 18th century" and "the 1700s" are false equivalents: "the 18th century" covers the years 1701–1800, while "the 1700s" covers the years 1700–1799. This is explicitly noted at WP:CENTURY. White Whirlwind 咨 06:06, 29 June 2017 (UTC)

- They're certainly not exactly the same, but when describing the timing of sound changes, it really doesn't matter whether the period being referred to contains the years 1700 or 1800 or not. Both "the 18th century" and "the 1700s" include 1701-1799. — Eru·tuon 19:03, 29 June 2017 (UTC)

- I find this discussion strange and more than a bit surreal. I can't fathom why anyone over the age of 10 (unless perhaps if they were not a native English speaker) would see incongruity in, say, "18th century" and "1740s". This is common and standard in all modern English prose, including in the main source for the "History" subsection of the article at hand. Additionally, I have never seen "the 1700s" used to refer to 1700–1709; the term would be something like "the first decade of the 18th century". The change from "18th century" to "1700s" makes the prose smack of a juvenile editor copying from the Simple English Wikipedia, and should have been reverted (I will do it now). In any case, it's also flat-out wrong, since "the 18th century" and "the 1700s" are false equivalents: "the 18th century" covers the years 1701–1800, while "the 1700s" covers the years 1700–1799. This is explicitly noted at WP:CENTURY. White Whirlwind 咨 06:06, 29 June 2017 (UTC)

Item of concern

"The advent of radio and television in the early 20th century established a national standard of American pronunciation that fully preserved historical /r/."

This sentence, which is unsourced, seems so wrong to me. Listen to old radio broadcasts, or movies from the 1930's, and non-rhoticity is rampant. I believe the prestige standard was actually non-rhotic at this time, and the shift (as reflected in movies and broadcasting) was post World War II. Does anyone know of reference sources that could be used to fix this? Thanks. Opus33 (talk) 03:10, 3 August 2017 (UTC) P.S. to whoever did the work: nice article. P.P.S. Television was invented in the 1920's but did not become widely distributed until after WW2, hardly "early 20th century".

- @Opus33: You are incorrect – that sentence you quoted is indeed sourced, but the inline citation is in its appearance in the body. Take the time to read the "History" section before commenting next time. WP:LEADCITE states that leads do not necessarily require inline citations, and so I generally do not use them because the lead should contain only material summarized from the body that should always be already sourced. White Whirlwind 咨 04:40, 3 August 2017 (UTC)

@Opus33, White whirlwind, and LakeKayak: Sorry to be a pain, but I don't see how Opus's main concern has been addressed. I've read both this section and the one below. Indeed, the prestige standard was non-rhoticity, as Opus says, up until WWII, as various sources on the page Mid-Atlantic accent can attest. So what does the Fisher source mean that "Non-rhotic pronunciation continued to influence American prestige speech until the 1860s, when the American Civil War shifted America's centers of wealth and political power"? Does it mean that this shift took place in a span of year ranging from the 1860s to almost the 1960s??? On the contrary, it seems that in only a much shorter span of years (something like the 1940s to 1960s) did the non-rhotic prestige find itself on the outs. Wolfdog (talk) 13:48, 26 August 2017 (UTC)

- I don't have time to delve deeply into this at the moment. The only source on the Mid-Atlantic article that I would put on reliability par with the CHoEL is the Labov one, and he is just talking about the old elocution schools that only a small fraction of the population would have attended. That Metcalf book has never been academically reviewed (I couldn't find a single one). Please revert your changes or at least hold off until you can get some more eyeballs on this. Stick to the major works in the field, too, please. White Whirlwind 咨 02:32, 14 September 2017 (UTC)

- Well, since even Labov agrees that WWII was the turning point for prestige speech being rhotic vs. non-rhotic, I'm happy to hold off with any further edits, but will leave my current edit for now. Remember, we're talking about prestige English but not necessarily mainstream English; certainly, Labov says r-dropping was presitigious until WWII, even if, yes, confined only to the tiny populations who went through old elocution schools (or who imitated such people), plus, of course, several regional East Coast dialects. As a side-note, what's a good/quick way you use to determine if sources have been academically reviewed? Wolfdog (talk) 20:00, 14 September 2017 (UTC)

More on non-rhoticity in American broadcasting and film

I've been checking up a bit. To review, the article currently says (twice):

when the advent of radio and television in the early 20th century established a national standard of American pronunciation, it became a rhotic variety that fully preserves historical /r/.

Here is what I've found bearing on this.

1. There is another WP article, Mid-Atlantic accent, that bears on the question. This article describes precisely the accent I had in mind when I posted my original comment, including its non-rhoticity and its prevalence in pre-World War II broadcasting and movies.

2. I also checked up on the source material, a published article by John Hurt Fisher. It says this (and only this):

By the time radio and television began to establish a norm of pronunciation, they favored the rhotic Middle Western pronunciation rather than the nonrhotic of Boston and Virginia.

Fisher does not say just when "radio and television began to establish a norm of pronunciation". The fact that he mentions television, which (to reiterate) was widely viewable only after World War II, suggests that he does not mean that his sentence should be taken to bear on what happened pre-war.

In sum, I think the sentence under discussion misleads readers in three ways:

- In omitting the prevalence of non-rhotic speech in early movies and broadcasting

- In implying that it was the early 20th century when broadcasting promulgated non-rhotic speech among Americans

- In suggesting that television was widespread in the early 20th century

Sincerely, Opus33 (talk) 17:10, 25 August 2017 (UTC)

- Thanks for actually bothering to check the original source (by the way, Fisher [2001] is not an "article", it's a chapter in a book) before commenting. Your first point is not persuasive because none of the sourced statements in the theatrical section of the Mid-Atlantic article mention rhoticity. If that article has other such statements in it that aren't sourced (I didn't see any), we should all remember that using Wikipedia articles as sources for other articles is expressly forbidden (WP:CIRCULAR). Your subsequent two points are good ones and can be easily fixed. I will do so now. White Whirlwind 咨 20:26, 25 August 2017 (UTC)

- Hello, I have now checked another source in hard copy, Speak with Distinction by Edith Skinner, probably the leading reference source on how to speak "Mid-Atlantic" stage English, and cited prominently in Mid-Atlantic accent. Pages 168-190 of the book present highly detailed information about how to "drop r's" in Mid-Atlantic speech. So, "none of the sourced statements in the theatrical section of the Mid-Atlantic article mention rhoticity" is not accurate at all. Sincerely, Opus33 (talk) 22:27, 21 September 2017 (UTC)

History of American non-rhoticity

- According to the article, "By the 1770s, postvocalic /r/-less pronunciation was becoming common around London even in more formal, educated speech" and "By the 1790s, fully non-rhotic pronunciation had become common in London and surrounding areas, and was being increasingly used even in more formal and educated speech". This suggests that non-rhoticity in the U.S. would have either developed in those same decades or, even more likely, sometime later on. However, Presidential Voices (2004) by Allan Metcalf claims that the early Virginian presidents like Washington and Jefferson would have grown up with non-rhotic accents, though these two were born in 1732 and 1743 respectively, decades before non-rhoticity had solidified in London, let alone in North America. Any way to make sense of this apparent contradiction? In fact, I feel there are really two theories on the rise of non-rhoticity in North America: one that it originated in 1700s colonial America and the other that it originated in the 1800s as an imitation of the London prestige. Obviously, these are not mutually exclusive and William Labov seems to only focus on the latter, but is there any credence to the former, which is the theory that Metcalf seems to push? Wolfdog (talk) 13:25, 26 August 2017 (UTC)

- I just did some reading in American English: Dialects and Variation by Walter Wolfram and Natalie Schilling-Estes, which seems to take the "mutually inclusive" perspective: i.e., that Jamestown settlers in 1607 and after would have been variably non-rhotic, since that was the developing trend in their homeland of southeastern England, but at the same time the growing non-rhotic London prestige in the 1800s also helped maintain that non-rhoticity in such coastal American settlements and cities. Wolfdog (talk) 15:10, 27 August 2017 (UTC)

- Continuing my one-sided conversation about this topic (which nonetheless merits analysis right here on this talk page), I notice Thomas Paul Bonfiglio's Race and the Rise of Standard American gives some support in favor of American non-rhoticity being an older (maybe even colonial?) feature and against it being a 19th-century London-imitating phenomenon... at least, in New York City. Specifically, NYC rapidly grew in population only in the mid-19th century, thanks to new Erie Canal commerce, and "would have been sufficiently exposed" to rhoticity, yet its dialect did not become rhotic. Therefore, "one must conclude that the dropped /r/ of New York City was not the result of British influence in the nineteenth century, but instead the result of the resistance of indigenous pronunciation to external influences" (51). Personally, I'm not sure why this conclusion necessarily follows, but this a certified linguist and he certainly says it with confidence. (For fun though, here's my own uncertainties anyway: Bonfiglio's conclusion seems to me based off some startlingly narrow assumptions. The two non-rhoticity theories are obviously not mutually exclusive, for one. Also, any other number of pro-British theories remain possible. For example: a non-native pronunciation affected by the posh upper class certainly could gradually spread throughout the population as an eventually native feature among all social classes of the city. Then there's the [admittedly unlikely] possibility that neither British-embracing nor immigrant-resisting influences are at play. As far as I can see, other than Bonfiglio's confident tone, he hasn't actually made a particularly convincing point, has he? And now that I think of it, is he even saying NYC non-rhoticity started before the immigration waves and was intensified by them or it started only just during and because of the immigration waves? Those are two rather different arguments.)Wolfdog (talk) 04:51, 27 March 2020 (UTC)

IPA is an indecipherable code that excludes those who have not studied it

Why, particularly here on a page about pronunciation, are the pronunciation guides provided solely in IPA? IPA may be superior to other more traditional guides, but its rigid adoption by Wikipedia authors makes the pronunciation guides useless for anyone who has not studied IPA. Providing only IPA unnecessarily and narrow-mindedly creates a barrier to understanding. I am not going to take the time to study IPA. Most people who come to Wikipedia are not going to study IPA. When I need information about a subject that includes the pronunciation of its terms, I have learned to avoid Wikipedia and look elsewhere. Sad! Gillead_Fnott (talk) 17:20, 6 May 2018 (UTC)

- @GilleadFinknottle: "Sad!" --> President Trump, is that you? Anyway, this page is about rhoticity in English, not the IPA, and so is not the proper forum for venting your spleen over Wikipedia's use of IPA. For that you'd want the Manual of Style's pronunciation page. On a personal note, I was once an IPA ignoramus as well, but I had to learn it for some graduate school work and boy am I glad I did. I wish I would've done it earlier – I can't believe my secondary school system never covered it. I hope you feel better now that you've gotten that off your chest. White Whirlwind 咨 00:23, 7 May 2018 (UTC)

- Mathematical expressions are a code that excludes those who have not studied them. The periodic table is a code that excludes those who have not studied it. English orthography is a code that excludes those who have not studied it. It is unreasonable to expect to be able to appreciate an encyclopedic article about language, let alone about phonetics and phonology, without having studied the IPA. Nardog (talk) 06:33, 7 May 2018 (UTC)

Surprising French

The History section has a footnote (currently #11) with the following French citation from Lass (1999), p. 115: ...dans plusieurs mots, l’r devant une consonne est fort adouci, presque muet & rend un peu longue la voyale qui le precede. Could someone please check if Lass is cited correctly with the word forms voyale and precede instead of the expected voyelle and précède? If so I suggest we insert sics after these highly unusual word forms. Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 12:06, 19 September 2018 (UTC)

- @LiliCharlie: Lass (1999: 115) is cited correctly, but Flint (1754: 69) has "voyelle" and "précede" (but not "précède"; I don't know what the standard form of the word was back then). So it seems either Lass or the 1740 print of Flint that got it wrong. Nardog (talk) 12:58, 19 September 2018 (UTC)

- The word précéder and its conjugated forms were written with an accent on each of the first two syllables from the 3rd (1740) edition of the authoritative Dictionnaire de l'Académie française onwards, see here for a remark on this and here for the word entry in the 4th (1762) edition of the dictionary. — I was unable to find former French forms of voyelle ending in -al, or more generally, in -a(u)l((l)e). — In all editions of the DAf, that is, since 1694, the only accepted spelling is voyelle. — According to the OED the English vowel derives from Old French (8th-14th c.) vouel (alternatively spelled vouyel, voyel, voieul; later OF voielle). Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 15:42, 19 September 2018 (UTC)

Also: 'qui LA précède' (not LE, consonne is feminine) stefjourdan — Preceding unsigned comment added by 2401:7000:B067:E200:85BF:B40F:B471:AD9B (talk) 01:19, 31 December 2018 (UTC)

- No, qui le précède is grammatically correct: the le doesn't refer to consonne, but to l’r devant une consonne. (Note that this expression takes the adjectives adouci and muet, not adoucie and muette, which makes it an obviously masculine noun phrase. In contemporary standard French names of letters are still masculine, though in several closely related Romance languages they are feminine.) Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 22:39, 19 February 2019 (UTC)

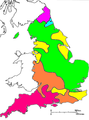

The maps need a revamp

No idea how you feel about maps but these two feel like the artist took quite some license when move parts of Wales to England. It's confusing for most of the world anyways to show just England and not the better known depiction of the geological southern part of the isle.

while the third one could be replaced with an svg version as well

Anyone up for the task? -- TomK32 (talk) 22:05, 19 February 2019 (UTC)

I think that the areas of Wales included were those that were in the Survey of English Dialects. Monmouthshire as a whole was included, plus one site in Flintshire that had been in Cheshire in the past.

I have just posted this on the discussion page for the multi-coloured map for the "farmer" end vowel. Re-posting here as I'm not sure if anyone reads the talk pages on maps.

Green in key

Is there any way to get the green in the key looking more like the green on the map? I saw this map on the article for the Survey of English Dialects and it's hard to tell that the two are the same. Epa101 (talk) 10:49, 22 February 2020 (UTC)

Isle of Man

Are you sure that the Isle of Man should be the non-rhotic colour? Whatever I've read on the Isle of Man from the SED always had it as rhotic. It's possible that this mistake was in the original source. Epa101 (talk) 10:49, 22 February 2020 (UTC)

trilled

This article is completely missing information about how the r sounded and mostly (only?) talks about its strength. Specifically there is not even any mention that it was usually or always trilled until fairly recently in most dialects. http://blogicarian.blogspot.com/2018/07/on-shakespeare-and-original.html and https://english.stackexchange.com/questions/298566/why-and-when-was-the-trilled-r-in-middle-english-replaced-by-the-modern-untrille cite sources that show our current quote of Jonson is missing the most important part, which clearly describes rolling/trembling/trilling. --Espoo (talk) 22:57, 12 September 2019 (UTC)

Try a Different POV; Don't speak of failing to pronounce r, but of pronouncing r as ə

The symbol r stands for a vowel (as in dirt and Bert, where the i & e are not pronounced). In much of England the symbol r has the pronunciation of the schwa (ə). Since we do not recognize the vowel schwa, though it is used all the time (but never written), people speak of England speakers as not pronouncing the r. I think that they do, but they pronounce it as schwa. If you study the vowels in mouth diagrams, you find that r and ə can be produced with the tongue in the same position, only lower for the ə. Thus while Americans are likely to say other (more accurately əther), people of England are likely to say "othə" (better put as əthə, uhthuh it might be carelessly written). (PeacePeace (talk) 06:21, 22 April 2020 (UTC))

- @PeacePeace: After /ɑː/ and /ɔː/ there's no trace of /r/ and the words car and more are pronounced 'cah' and 'maw'. Also, while American English contrasts word-final and preconsonantal /ə/ and /ər/, much of English and Welsh English does not, so that cheetah and cheater are both pronounced 'cheetuh' (rhotic AmE doesn't contrast /ər/ and /ɜr/, though, so that forward and foreword are both pronounced /ˈfɔrwərd/, word is also /ˈwərd/. There's a NURSE-LETTER merger in those varieties. But that's beside the point). The term non-rhotic is accurate. Kbb2 (ex. Mr KEBAB) (talk) 07:45, 22 April 2020 (UTC)

- Actually, complete /r/-dropping after open central/back unrounded vowels is a cross-linguistic phenomenon. In German, haar is pronounced [haː], whereas the Danish word arne is pronounced [ˈaːnə]. As in English, there's no distinction between /ar/ and /aːr/ in those varieties, except in some non-standard regional German (where /ar/ is [æː] and /aːr/ is [ɑː]). Kbb2 (ex. Mr KEBAB) (talk) 09:09, 22 April 2020 (UTC)

The term non-rhotic is accurate.

I don't even think that's what PeacePeace is arguing with. I don't know what is though. Nardog (talk) 09:16, 22 April 2020 (UTC)- Do you deny that r in England-English, is often pronounced as ə (schwa)? Could it be that where it is thought that r is not pronounced after a consonant (and a written vowel which is not pronounced) often r is pronounced, but as ə. However, after a pronounced vowel, the schwa is assimilated, as with "car"? Would you admit the observation that in languages, the symbol r may stand for at least 5 different sounds: a tongue tap, a tongue trill, a gargle, an American r, or ə? (PeacePeace (talk) 04:03, 26 April 2020 (UTC))

- If you write "the schwa is assimilated" in car the problem is with the word "is." It is true that [kɑə] for car once was an option; past phoneticians have described that stage. Later, however, the schwa was assimilated and elided. That is, historically the schwa was assimilated, but now it is completely lost, as is the [k] in knot. RP speakers no longer say [kɑə] ("kah-uh"), not even in careful speech. (Prevocallically the ancient /r/ resurfaces, of course, but as a consonant rather than a schwa.) Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 05:27, 26 April 2020 (UTC)

- @PeacePeace: The term non-rhotic covers both elision and r-vocalization that's not elision. In other, /r/ is fully elided and there's no trace of it. How can we know that? It's simple: in English English, /ə/ can be found where both /ə/ and /ər/ are found in North America, Ireland and Scotland: sofa, comma, better, dinner all contain a final /ə/ in non-rhotic speech of England. That's a phonemic merger. When it comes to /ɑː/, things are more complicated as many instances of /ɑː/ in RP correspond to /ɑːr/ in North America. In English accents that feature a short vowel in grass, bath and sample, that's even more true. The distribution of /ɑː/ is one of the greatest variables in English dialectology; in North America, for instance, /ɑː/ mostly corresponds to /ɒ/ in RP (also /ɔː/ in accents with the cot-caught merger - another variable) when you ignore loanwords and the sequence /ɑːr/ (RP /ɒr/ corresponds to /ɔːr/ in North America, but the former sequence appears only before vowels, like /ær/). So yes, /ɑː/ can be seen as being largely a product of r-vocalization (akin to /ɪə/), but not necessarily in RP (due to the trap-bath split). That's because what used to be a long a in English shifted to /eɪ/ a couple of centuries ago (Danish has undergone a very similar process). Does this answer satisfy you? Kbb2 (ex. Mr KEBAB) (talk) 12:42, 26 April 2020 (UTC)

- Gentlemen, forgive me for thinking that rhotic vs non-rhotic is not the best terminology for a discussion of the pronunciation of r. Or do you define non-rhotic to mean a dialect of English where an historical r (of some variety) was pronounced (in one of several ways), but no longer is pronounced, a philological approach? Does this terminology have any significance in synchronic linguistics with reference to the spoken language? Would it be more objective simply to list the variations in the pronunciation of words which are written with r? The term rhotic seems to imply a pronunciation like Greek ρ, which likely varied in different Greek speaking cities and in different eras in the history of the Greek language. And do you doubt that many Americans would say that in England (and southern USA) they are neglecting to pronounce r where in fact they are pronouncing it as a schwa? (PeacePeace (talk) 05:03, 28 April 2020 (UTC))

- See rhotic consonant. "Non-rhotic" is clearly defined in this article.

- It doesn't matter what they would say, what matters are the facts. Americans aren't deaf, they know that there's no trace of /r/ in car, more and letter in non-rhotic speech of England. In other cases, some might argue that there is some trace of /r/ in pronunciation, but that too is variable: near can be pronounced [ˈnɪə̯, ˈnɪɐ̯, ˈniə̯, ˈnjɜː, nɪː], depending on the speaker - and all of those pronunciations are RP. Sure can be [ˈʃʊə̯, ˈʃʊɐ̯, ʃʊː, ʃoː, ʃɔː], and square can be [ˈskwɛː, ˈskwɛə̯, ˈskwɛɐ̯, ˈskwæɐ̯]. Such a variation in pronunciation is clearly characteristic of a vowel, not a sequence of vowel + consonant. If there's /r/ in there, it's on a very abstract level. But there are some vowels which have little variation, e.g. the one in nurse [nəːs] - but again, to argue that it is pronounced with r just because it stems from historical short vowel + /r/ is circular logic. It is a pure monophthongal vowel in most of the non-rhotic speech, and it's typically heard as [œː] or [øː] by speakers of other Germanic languages. Neither of these vowels are perceived as rhotic (corresponding to historic vowel + /r/) by Dutchmen or Germans. Kbb2 (ex. Mr KEBAB) (talk) 06:33, 28 April 2020 (UTC)

- @PeacePeace: The term rhotic as used here was coined by John C. Wells in 1968 as a back-formation from rhotacism (< Latin rhotacismus < Greek rhōtakismós/ῥωτακισμός) which has been in use in English since 1834. The first attestation of the similar lambdacism dates back to 1658. Neither time-honoured English, Latin or Greek word ever referred to Greek letters or Greek-only sounds. Love —LiliCharlie (talk) 07:24, 28 April 2020 (UTC)

- Gentlemen, forgive me for thinking that rhotic vs non-rhotic is not the best terminology for a discussion of the pronunciation of r. Or do you define non-rhotic to mean a dialect of English where an historical r (of some variety) was pronounced (in one of several ways), but no longer is pronounced, a philological approach? Does this terminology have any significance in synchronic linguistics with reference to the spoken language? Would it be more objective simply to list the variations in the pronunciation of words which are written with r? The term rhotic seems to imply a pronunciation like Greek ρ, which likely varied in different Greek speaking cities and in different eras in the history of the Greek language. And do you doubt that many Americans would say that in England (and southern USA) they are neglecting to pronounce r where in fact they are pronouncing it as a schwa? (PeacePeace (talk) 05:03, 28 April 2020 (UTC))

- Do you deny that r in England-English, is often pronounced as ə (schwa)? Could it be that where it is thought that r is not pronounced after a consonant (and a written vowel which is not pronounced) often r is pronounced, but as ə. However, after a pronounced vowel, the schwa is assimilated, as with "car"? Would you admit the observation that in languages, the symbol r may stand for at least 5 different sounds: a tongue tap, a tongue trill, a gargle, an American r, or ə? (PeacePeace (talk) 04:03, 26 April 2020 (UTC))

"Especially ones written by women"

In the lead the there is a line which states "these /r/-less spellings were uncommon and were restricted to private documents, especially ones written by women". That last part, "especially ones written by women", feels off. The source where it comes from is not easy to get a hold of so I cannot confirm or deny that it is true, but even if it is, I feel as if there needs to be some sort of clarification as to why this is the case. BlastKast (talk) 17:41, 2 November 2020 (UTC)

Indian Englsh

Indian English is not rhotic. I say this as somebody who has lived and studied there for three decades, and is considered fluent in the language. I don't have time to look up sources and correct the article, but someone should look into this. At best, Indian English may be described as variably rhotic or semi-rhotic (the description of Jamaican English in the article seems accurate of the typical pronunciation in India, though the actual accents are very different.) As it is, Indian English as taught in most schools around the country is derived from British English as introduced to the country more than a hundred years ago. Any rhoticity is purely an influence of American movies and popular culture, and would be considered a corruption ("Americanized accent") of the actual standards of pronunciation in the country. 2601:249:8700:7790:48DC:9281:54A3:65FE (talk) 00:08, 10 November 2020 (UTC)

If you want some proof of this (not a reliable source I know), see the character Raj's accent on the Big Bang Theory and note the lack of rhoticity, especially in the early seasons when his accent is mocked by the other characters. While the show is a comedy and a large part of his way of talking is exaggerated for comedic effect (especially in later seasons), it is close to what Indian English sounds like in terms of rhoticity. 2601:249:8700:7790:48DC:9281:54A3:65FE (talk) 00:08, 10 November 2020 (UTC)

- I definitely agree with what you have stated and I have just moved Indian English (and even Pakistani English) from the rhotic examples to the variably rhotic examples as, like you've stated, Indian English definitely is semi/variably rhotic. Broman178 (talk) 13:49, 28 March 2021 (UTC)

Mid-Atlantic accent

The fact that the Mid-Atlantic accent died out shortly after WWII is because it was non-rhotic. It is an example of non-rhoticity not lasting much past the war. The fact that it lasted a few years beyond the war itself doesn't make it an exception to the general trend of decline. Its hey-day was before and during the war, just as one would expect of a non-rhotic American accent. Wolfdog (talk) 15:52, 19 September 2021 (UTC)

Sentence doesn’t make sense

This is sentence doesn’t make sense: “In the mid-18th century, postvocalic /r/ was still pronounced in most environments, but by the 1740s to 1770s it was often deleted entirely”. The mid 18th century couldn’t be better defined than by 1740s to 1770s. Rickogorman (talk) 08:10, 29 October 2022 (UTC)

Much of this article is indecipherable or makes no sense

I propose that someone familiar with this topic try to simplify the article. I came away a lot more confused after reading this page. For example there is no explanation what the "Goat–comma–letter merger" is, just a lot of discussion about it. "Goat" doesn't sound remotely like "letter". Out of most scientific content on Wikipedia I find the phonology articles to be the most frustrating... they're like reading transmission repair manuals. -Rolypolyman (talk) 15:03, 22 August 2023 (UTC)

- You're right that it is not only poorly written but heinously named. I am almost certain that Wells (1982), who is entirely cited in that section, never calls it such a misleading name. In fact GOAT is not merged with commA and lettER, but rather GOAT in the syllable-final position of some polysyllabic words. If you're just trying to figure this out, it is saying that in some accents, like working-class London ones, "yellow" and "yeller" and "yella" can all sound the same (like "yella"). Should probably be both renamed and rewritten. Wolfdog (talk) 15:59, 22 August 2023 (UTC)