Tales from the Gimli Hospital

| Tales from the Gimli Hospital | |

|---|---|

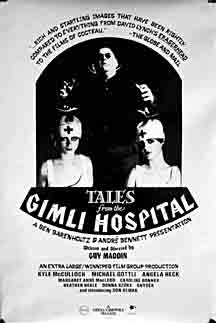

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Guy Maddin |

| Written by | Guy Maddin |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Guy Maddin |

| Edited by | Guy Maddin |

| Music by | Laurence Mardon |

| Distributed by | Cinephile (Canada) Circle Films (United States) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 72 minutes |

| Country | Canada |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $22,000 |

| Box office | $138,380 |

Tales from the Gimli Hospital is a 1988 film directed by Guy Maddin. His feature film debut, it was his second film after the short The Dead Father. Tales from the Gimli Hospital was shot in black and white on 16 mm film and stars Kyle McCulloch as Einar, a lonely fisherman who contracts smallpox and begins to compete with another patient, Gunnar (played by Michael Gottli) for the attention of the young nurses.

Maddin had himself endured a recent period of male rivalry and noticed that he found himself "quite often forgetting the object of jealousy" and instead becoming "possessive of my rival."[1] The film was originally titled Gimli Saga after the amateur history book produced locally by various Icelandic members of the community of Gimli (Maddin himself is Icelandic by ancestry).[2] Maddin's aunt Lil had recently retired from hairdressing, and allowed Maddin to use her beauty salon (also Maddin's childhood home) as a makeshift film studio (Lil appears in the film briefly as a "bedside vigil-sitter in one quick shot [taken] just a couple of days before she died" at the age of 85).[2] After Maddin's mother sold the house/studio, Maddin completed the remaining shots of the film at various locations, including his own home, over a period of eighteen months. Maddin received a grant from the Manitoba Arts Council for $20,000 and often cites that figure as the film's budget, although also estimates the actual budget between $14,000 and $30,000.[2]

Plot

The film opens on two young children whose mother is dying in the present-day Gimli, Manitoba hospital. During a visit to see her, the children's Icelandic grandmother launches into the grim and convoluted tale of Einar the Lonely, a patient in a far-distant-past version of the same hospital—in "a Gimli we no longer know," as the grandmother puts it. The rest of the film consists of Einar's story.

Einar (Kyle McCulloch) succumbs to a smallpox epidemic and is admitted to the Gimli hospital for treatment, where he meets his neighbor Gunnar (Michael Gottli). While both are at first pleased to have a friend nearby in their time of illness, the two men soon begin competing for the attentions and affections of the hospital's beautiful young nurses. Gunnar outperforms Einar in this regard, given his storytelling abilities and his skill at carving birch bark into the shape of fish. The hospital is built above a stable (for heat from the animals) and director Maddin appears in a cameo as a surgeon who operates while patients are told to observe a badly-acted puppet show as a sort of anesthesia.

Gunnar borrows Einar's fish-carving shears and recognizes the decorated pair of shears as uncannily similar to those he buried with his wife Snjófridur (Angela Heck). Gunnar recalls the story of their courtship and her death from smallpox she contracted from Gunnar. His aboriginal friend, despite Gunnar's protests, then laid her body to rest in the traditional aboriginal manner, on a raised platform with tokens and gifts including the shears. Einar relates to Gunnar the story of how he came to possess the shears: while wandering in the dark one night he discovered the corpse of a beautiful woman on a raised burial platform (who he now realizes must have been Snjófridur). Einar stole the tokens buried with her and had sex with her corpse.

Gunnar is furious but too weak to take immediate revenge on Einar, and coincidentally a fire breaks out on the hospital roof. The Icelanders put out the fire by pouring milk over it, which then drips down into Gunnar's face and blinds him. A blackfaced minstrel is buried and Einar contemplates further destroying Gunnar through carving him up with the selfsame shears stolen from his wife's corpse. Einar and Gunnar exit the hospital and wander around feverishly. Einar observes Lord Dufferin giving a public speech. Einar hallucinates that Lord Dufferin is the mythical Fish Princess. The men end up in a field together along with a Shriners Highland Pipe Band and begin to Glima Wrestle—a traditional competition where fighters graps each other's buttocks and take turns lifting one another up until one collapses. They tear each other's clothes and claw at each other's buttocks until they bleed, then both collapse.

Einar is later back in his small shack/fish smokehouse and is visited by a recovered and no-longer-blind Gunnar and his new fiance. They happily saunter along the beach of Lake Winnipeg while Einar regards them jealously, still Einar the Lonely. The scene returns to the present-day Gimli where the children are informed that their mother has died. They ask the storytelling Amma to be their mother and she says "no" but that she will still visit "if your father lets me." They ask about heaven and she prepares to tell another story as the film ends.

Cast

- Kyle McCulloch as Einar the Lonely (and also a minstrel in blackface)

- Michael Gottli as Gunnar

- Angela Heck as Snjófridur

- Margaret Anne MacLeod as Amma

- Heather Neale as Granddaughter

- David Neale as Grandson

- Don Hewak as John Ramsay

- Ron Eyolfson as Pastor Osbaldison / Patient (as Ronald Eyolfson)

- Chris Johnson as Lord Dufferin

- Donna Szöke as Fish Princess

Production

Guy Maddin proposed a 40-50 minute short, titled Gimli Saga, loosely based on the Icelandic settlement of Gimli. In 1987, he learned that the Winnipeg Film Group was offering a $20,000 film grant. The application deadline was the next day and Maddin combined some ideas into three to four pages. He lost the grant competition, but submitted the idea to the Manitoba Arts Council. He asked for $9,000, but the council gave him $20,000. Maddin's final screenplay was eight pages long.[3][4]

The film had a budget of $22,000 (equivalent to $48,542 in 2023 and Greg Klymkiw raised $40,000 from the Winnipeg Film Group to market the film. Maddin stated that the official budget figure was inaccurate and "could have been as high as $30,000, or as low as $14,000".[4][5]

Filming occurred over one year from 1987 to 1988. Some outdoor scenes were shot in Gimli and most of the interior scenes were filmed in Maddin's aunt house, a former beauty salon. Several actors in the film were amateurs who were not paid. Maddin hired a cinematographer, but he refused to come after the first day of shooting. He instead taught Maddin how to use the 16mm Bolex camera. Maddin hid powerlines that were in frame by applying vaseline onto the lens.[6]

The film uses music from Zero for Conduct, Vess Ossman, and Icelandic folk music from the collection of Maddin's aunt.[7]

Greg Klymkiw, who met Maddin while they were studying at the University of Winnipeg, became the film's executive producer after seeing its rough cut. Klymkiw convinced Maddin to make the project feature-length. Steven W. Snyder, a film professor at the University of Manitoba, was listed as a producer in the credits for providing meals to Maddin and allowing him to audit his course without paying tuition.[8]

Release

Tales from the Gimli Hospital premiered at the Winnipeg Film Group Cinematheque in April 1988, and Klymkiw spent $5,000 on the event. Klymkiw submitted the film to the major festivals in Montreal, Toronto, Vancouver, and Halifax.[9] The film was rejected by the Toronto Festival of Festivals when a divided jury mistook its anachronistic style as unintentionally ill-crafted.[10]

Andre Bennett saw the film at the Montreal World Film Festival in August. He did not know who Maddin was, but paid $5,000 to buy the distribution rights for his company Cinephile. Five English-language revival houses in Montreal closed and exhibitors opened a new one in a 1,000 seat theatre. The revival house asked for Tales from the Gimli Hospital to be the first film shown at the theatre. Klymkiw agreed and it opened on 30 September 1988.[11]

Klymkiw decided to show the film at the International Filmfestival Mannheim-Heidelberg rather than attempt to gain an invitation to the Berlin International Film Festival as he could show the film at the Berlin forum for non-competing films. Ben Barenholtz, who distributed David Lynch's Eraserhead, saw the film at the Berlin forum and organized showings at American film festivals.[12]

The film earned $116,000 in Canada and $22,380 internationally by May 1992. $105,000 was from television, $9,700 from theatrical, and $2,400 from non-theatrical sources. Cinephile spent $29,000 on the film in the same period.[4][13]

It became a cult success and established Maddin's reputation in independent film circles.[2] Maddin received a Genie Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay as well, although the script consisted of a series of Post-it notes.[2][10] Along with Maddin's debut short film, The Dead Father, Tales from the Gimli Hospital was released to home video on DVD.[14]

Critical reception

The film received generally positive reviews, with review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes reporting a 71% approval rating based on 7 reviews.[15] Reviewers, although generally positive, also seemed perplexed by the film: Jonathan Rosenbaum commented on its "moment-to-moment invention and genuine weirdness"[16] and Noel Murray of the Onion A.V. Club similarly noted that "[Maddin] self-consciously borrows from dozens of sources, including radio dramas, Our Gang shorts, hygiene films, school plays, stag pictures, Universal horror, ethnographic documentaries, and the indie weirdness of John Waters and David Lynch."[17] The 1989 review in The New York Times referred to its "midnight-cult status" and lengthy run at New York's Quad Cinema, and noted that "Many bits of [the film's] seemingly surreal business supposedly draw on ancient Icelandic customs, like using oil squeezed from fish as a hair pomade, cleaning the face with straw, and sleeping under dirt blankets."[18]

Gerald Peary stated that it was the best Canadian film of the year. David Chute, writing in Film Comment, said the film was "exactly the kind of audacious filmmaking Canada needs if it is ever to spruce up its dour, stiff, humanistic, NFB image".[19]

The mayor of Gimli criticized the film for portraying the town's people as "some sort of barbarians".[20]

Awards and nominations

- Nominated: Best Original Screenplay – Guy Maddin

References

- ^ Noam Gonick (1997). "Waiting for Twilight". Documentary. Retrieved 2012-11-21.

- ^ a b c d e Vatnsdal, Caelum. Kino Delirium: The Films of Guy Maddin. Winnipeg: Arbeiter Ring Publishing, 2000. Print. ISBN 1-894037-11-1

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 172-175.

- ^ a b c Melnyk 2004, p. 194.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 175.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 175-177.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 178.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 178-179.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 179-180.

- ^ a b Mark Peranson. "Canadian Film Encyclopedia entry". Archived from the original on 2013-02-22. Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 182-183.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 183-184.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 185.

- ^ Tales from the Gimli Hospital. Dir. Guy Maddin. Kino Video, 2000. DVD.

- ^ "Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988)". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Retrieved 2012-12-28.

- ^ Jonathan Rosenbaum. "Tales from the Gimli Hospital [review]". Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- ^ Noel Murray. "Tales from the Gimli Hospital [review]". Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- ^ Stephen Holden. "Tales from the Gimli Hospital [review]". Retrieved 2013-01-02.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 183.

- ^ Posner 1993, p. 180.

Works cited

- Posner, Michael (1993). Canadian Dreams: The Making and Marketing of Independent Films. Canadian Independent Film Caucus. ISBN 1550541145.

- Melnyk, George (2004). One Hundred Years of Canadian Cinema. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 080203568X.