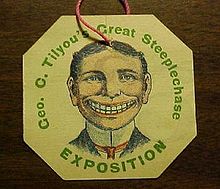

Steeplechase Face

The Steeplechase Face was the mascot of the historic Steeplechase Park, the first[1] of three amusement parks in Coney Island, Brooklyn, New York.[2] It remains a nostalgic symbol of Coney Island and of amusement areas influenced by it.[3] It features a man with a wide, exaggerated smile which sometimes bears as many as 44 visible teeth. The image conveys simple fun,[4] but was also observed by cultural critics to have an undercurrent of Victorian-era repressed sexuality.[5]

It was also known as the Funny Face after the park's slogan "Steeplechase – Funny Place" or as Tillie, after the park's founder George C. Tilyou. It has also sometimes been named Steeplechase Jack. The mascot represented the area's wholesomeness and neoclassical architecture combined with its veneer of hidden sexuality.[3][6][5] Though the park was a "family-friendly" area, it was nearby the "freer sexual expression of the dance halls, beaches, and boardwalk."[7]

The "Funny Face" logo has become an iconic symbol of Coney Island.[3]

History

Introduced in 1897 with the park's opening, it existed in a variety of forms for most of its history, and was only standardized as a design in the late 1940s.[8]

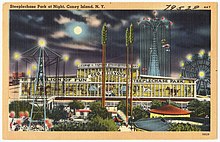

The face's most prominent appearance in Coney Island was in glass on the exterior of Steeplechase's Pavilion of Fun,[9] created when the park was rebuilt in 1909.[10]

The pavilion was destroyed by Fred Trump in 1966[11][9] in an unsuccessful attempt to create condos on the site.[12]

Impact

The smile of the Joker, a Batman villain, may have been partially inspired by the face.[13][14] The face is sometimes seen as an evil clown today, but this was not the original understanding.

The face also appeared at other Tilyou amusement properties, such as Steeplechase Pier in Atlantic City, and was also copied regionally, as with the Tillie of Asbury Park.

The face remains a popular symbol of Coney Island, embraced by many neighborhood institutions and businesses. A version is used in the logo of Coney Island USA, and for a time another, more clown-like, version was used by Coney Island Brewing Co. It is used in parts of the modern Luna Park, particularly in its "Scream Zone".

As of 2019, the Steeplechase Face continues to appear as sticker art in Coney Island.[15]

An exhibit on the history of the face was shown by the Coney Island History Project in 2014.[16] An exhibit on Coney Island's history, which included artifacts of the face, was displayed at the Brooklyn Museum in 2015.[17][18]

See also

- Tillie (murals)

- Alfred E. Neuman

- Mickey Mouse, mascot of The Walt Disney Company

References

- ^ Ryan, Hugh (March 5, 2019). When Brooklyn Was Queer: A History. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-250-16992-1.

- ^ "George Tilyou's Steeplechase | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved December 28, 2022.

- ^ a b c Cross, G.S. (2005). The Playful Crowd: Pleasure Places in the Twentieth Century. Columbia University Press. pp. 39–40. ISBN 978-0-231-12724-0.

- ^ ""The Face Of Steeplechase" Opening May 24 at the Coney Island History Project". Coney Island History Project. May 19, 2014. Retrieved July 10, 2021.

- ^ a b ""The Face of Steeplechase" at the Coney Island History Project". Brooklyn Paper. May 30, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2019.

- ^ Goldfield, David R. (2006). Encyclopedia of American urban history. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. p. 185. ISBN 978-1-4522-6553-7. OCLC 162105753.

- ^ Ryan, Hugh (March 5, 2019). When Brooklyn Was Queer: A History. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-250-16992-1.

- ^ Silverman, Stephen M. (May 7, 2019). The Amusement Park: 900 Years of Thrills and Spills, and the Dreamers and Schemers Who Built Them. Running Press. ISBN 978-0-316-41647-4.

- ^ a b "Remembering the day Trump's dad destroyed a Coney icon". Brooklyn Paper. May 20, 2016. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "The Lambs' Gambol.; Brooklyn Amusements. Greater Dreamland, Opening Steeplechase Park". The New York Times. May 16, 1909. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved July 11, 2019.

- ^ Schulz, Dana (May 17, 2016). "52 years ago, Donald Trump's father demolished Coney Island's beloved Steeplechase Park". 6sqft. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

- ^ "Coney Island History | Steeplechase Park". Heart of Coney Island. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Richardson, Chris (October 27, 2020). Batman and the Joker: Contested Sexuality in Popular Culture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-16970-6.

- ^ Morton, Drew (November 28, 2016). Panel to the Screen: Style, American Film, and Comic Books during the Blockbuster Era. Univ. Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1-4968-0981-0.

- ^ "What's Left of Coney Island? Part 1: The Golden Age". Coaster101. September 5, 2019. Retrieved June 18, 2022.

- ^ Bredderman, Will (May 23, 2014). "Photo exhibit celebrates Coney's iconic countenance". Brooklyn Paper. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Bortolot, Lana (November 19, 2015). "Coney Island: Signs, Schooners and Spook-A-Rama". Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved July 11, 2021.

- ^ Ziv, Stav (November 28, 2015). "An Offsite Tour of Coney Island, Through Time". Newsweek. Retrieved July 11, 2021.