Stanhope and Tyne Railway

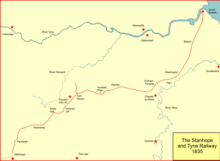

The Stanhope and Tyne Railway was an early British mineral railway that ran from Stanhope to South Shields at the mouth of the River Tyne in County Durham, England. It ran through the towns of Birtley, Chester Le Street, West Stanley and Consett. The object was to convey limestone from Stanhope and coal from West Consett and elsewhere to the Tyne, and to local consumers. Passengers were later carried on parts of the line.

The line opened on 15 May 1834, but it was not financially successful. It had been formed by a partnership, and the heavily indebted partners floated a new company, the Pontop and South Shields Railway, to continue operation and take over the debt. Part of the line was bought by the Derwent Iron Company, which later became the Consett Iron Company.

Much of the S&TR system was built through hilly, sparsely populated terrain across the moors of County Durham, and it incorporated several rope-worked inclines as well as using horse traction and steam locomotives on level sections.

Dependent on the activity of mineral workings, and subject to competition from more modern routes, the line closed in stages in the 20th century, although a short section near South Shields is still extant; today much of the route is used as the Consett and Sunderland Railway Path, part of the national Sustrans foot and cycle path network.

Waggonways

The Durham and Northumberland coalfield was rich in the mineral, and it was extracted in increasing volumes from the Middle Ages. Transport of the heavy mineral to market was expensive and difficult; water transport, on rivers and by coastal shipping was the most practicable, and the earliest pits were close to waterways, particularly the River Tyne and the River Wear. The deposits very close to the waterways soon became worked out, and the location of the mining moved progressively away in the seventeenth century, requiring longer transits overland.

The mineral could be conveyed to a quay by cart. Even in the early decades of the nineteenth century, there were very few public roads, and the carts made their way across private land, paying a wayleave to the landowner. The wayleave was a contract for permission to cross the land in return for a payment, usually based on a rate per unit of weight.

Even so, crossing undeveloped land by cart was slow and difficult, and waggonways were developed; at first they consisted of wooden rails, and individual wagons were hauled along the route by horse traction. In the course of time a considerable number of such waggonways were constructed in the area. The waggonways too required wayleaves to traverse privately held land.[1][2][3][4]

Formation of the Stanhope and Tyne

Early in 1831, Pontop Colliery (a landsale pit[note 1]) at Medomsley was advertised to be let.[5] William Wallis of Westoe (near South Shields) found the potential attractive and later in the year he agreed to leases of coal seams at West Consett and Medomsley, and limestone quarries at Stanhope. A railway would be needed to connect those places, and a partnership was formed. They arranged wayleaves to get their line from Consett to Stanhope, avoiding the expense of obtaining an act of Parliament. Stanhope was the location of extensive reserves of limestone, required in the process of smelting iron ore. At this stage, the plan was to use the Tanfield Waggonway[note 2] to transport the materials to the Tyne. As well as the limestone quarries at Stanhope, there were limekilns, producing quicklime.[4][6]

The partnership was formalised as the Stanhope Railroad Company under the deed of 30 January 1832 and the company reviewed the means of reaching the Tyne. The waggonway had the disadvantage of reaching the Tyne at the mouth of the River Derwent. As this was upstream of Newcastle bridge, the size of vessels reaching the berth was seriously limited, and it was decided to make an independent railway to a downstream location, at South Shields.

This would require considerably more capital than had been envisaged so far, and on 20 April 1832 an unincorporated[clarification needed] company, the Stanhope and Tyne Railroad Company, was formed for the purpose. This much more ambitious scheme required engineering expertise, and Thomas Elliot Harrison was appointed as the company's engineer. Harrison later became the first General Manager of the North Eastern Railway. Robert Stephenson was appointed consulting engineer, and he accepted his fee of £1,000 in stock of the company.

Although the scheme was now to be a considerable railway with an estimated capital of £150,000, in the interests of keeping confidential the rich mineral resources to be exploited, the company decided to continue the practice of arranging wayleaves rather than applying to Parliament for authority to build the line. In the event this resulted in massive charges being demanded by the landowners on the eastern section, averaging £300 a mile annually. The wild hills of the western section were less useful agriculturally and the wayleave fees were considerably less. Nonetheless the annual wayleave charge was about £5,600.[1][4] Most of the capital required for the construction was found by London financiers.

Construction and opening

The terrain at the western end of the line was exceedingly difficult due to its hilly nature and the high altitude; construction at Stanhope started in July 1832.

The eastern section across much easier terrain was begun in May 1833. From Kyo (near Annfield Plain) eastward to the Durham turnpike road near Pelaw Grange, it had been intended to take over the Beamish Colliery Railway and use it for the line. The Beamish had recently been converted from wooden rails to iron rails; it was to be reached along the old Shield Row waggonway. However the negotiations with Morton John Davison for the purchase of his railway fell through, and the Stanhope and Tyne was forced to fall back upon a line running by way of West Stanley to Stella Gill and thence to the Durham road. On 17 May the tenders were let, and the works began very soon afterwards. The South Shields Improvement Commissioners objected to the railway passing through the town at street level, and the Company was forced to alter the line to run at a higher level, crossing the main roads by bridges; these were completed in November, 1833.

Early in May 1834, the first locomotive (built by Robert Stephenson & Company) was placed on the line at South Shields,[7][8][9] and on 15 May the upper part of the line, a section of 15+1⁄4 miles (24.5 km) from Stanhope to Annfield, was opened for traffic.

The day was marred when a shackle broke on a set of four wagons, conveying 40 people, on the Weatherhill incline. The wagons ran away down the incline and were diverted into a siding containing spare wagons; a man and a boy were killed.[10][11]

The eastern section was opened on 10 September 1834, the first public railway on Tyneside.[12] Horse traction was used as well as locomotives, and in the hilly section there were inclines worked by stationary engines as well as self-acting inclines. The first consignment of coal was brought from the Medomsley collieries in a train of 100 wagons, and was loaded on a ship named "Sally".[1][6][10][13]

There were three drops or staiths at the South Shields quays, of a design considered to be advanced for the period; they were capable of dealing with 25 to 35 chaldrons per hour, and the berths could take vessels at low water of spring tides. The chaldrons were lowered to the ship on a swinging derrick; as they descended the tension on the restraining cable increased; a 5-ton chain was housed in a shaft, and at first it was coiled on the base. As the load descended the chain was increasingly pulled up, neatly counterbalancing the weight of the loaded chaldron; when the chaldron was discharged the weight of the chain pulled it back up.[14]

The main line was 33+7⁄8 miles (54.5 km) in length; there was a branch to Medomsley Colliery (1+1⁄4 miles (2.0 km)), and in 1835 a branch to Tanfield Moor colliery was opened, partly by restoration of an earlier waggonway, 2+1⁄8 miles (3.4 km), this was known as the Harelaw branch. There were no large towns on the line of route, which was planned purely for mineral transport.[15] The rails used on the line were of fish-bellied form, weighing 20 and 40 pounds per yard (10 and 20 kg/m), on stone blocks. The gauge of the line was 4 feet 8 inches (1,420 mm).[6]

In operation

The original proprietors had forecast considerable profits but this did not prove to be the case. Dividends of 5% were declared in 1835 and 1836, but these were paid from capital, not income.[1][6] The finances of the company were mismanaged and traffic did not reach expected volumes.[4]

The company burnt lime at Stanhope and Annfield, consuming nearly 10,000 tons of coal in the process; the resultant quicklime was distributed at seven depots, and it was a significant traffic in the early years,[15] but it was not profitable and it was discontinued in 1839.[6]

Except for one locomotive with four uncoupled wheels, the S&T had 0-4-2 locomotives, of which eight were built by Robert Stephenson and Company.[16] There were seven locomotives on the line by 1837.[15]

On 16 April 1835, the railway began to carry passengers, between South Shields and Durham Road, near the corner of Lambton Park. At first this was free of charge in coal wagons, but later in open carriages attached to the coal trains. The landowners now demanded higher charges for the wayleaves on the grounds that the earlier arrangement had been for the carriage of minerals only.[1]

The engineer of the line, T. E. Harrison, recorded:

It as only the force of circumstances that compelled us to take passengers at all. We had constant applications from poor people to ride on the coal waggons and, at first, permission was granted them to ride on the waggons without any payment at all, then passenger carriages were put on the way to save the trouble of these applications and to obviate the risk of accidents. We first put on an open carriage attached to the coal train, afterwards we ran a coach once a fortnight on pay days with an engine at considerable loss. In 1835, from 16 April, we carried 2,814 passengers. There was a considerable loss that year by carrying passengers, not less than £220. In 1838 we carried 17,490 passengers. There was an apparent gain that year of £117 15s. In 1839 we carried 15,010 passengers. In that year I consider the loss was £166 6s. 10d. Up to the close of 1839 I think there was distinctly a loss to the Company and I recommended the directors to discontinue it. They thought it a great public convenience and determined not to discontinue it.[17]

Route

The quarries at Stanhope are at an altitude of 796 feet (243 m) above sea level. The railway left the quarry sidings and turned north up the hillside, by rope worked inclines. From Stanhope to the Crawley engine was 1⁄2 mile (0.8 km) long on gradients of 1 in 8 and 1 in 12, passing through Hog Hill tunnel, about 120 yards (110 m) long. At the Crawley engine (1,223 feet (373 m) above sea level) the ropes were changed and the sets of wagons were drawn up to the Weatherhill engine, over 1 mile (1.6 km) away, over gradients of 1 in 21 and 1 in 13.

From Weatherhill the line climbed on a further rope-worked incline at 1 in 57 to the summit level at Parkhead, 1,474 feet (449 m) above sea level.[note 3] This was the highest railway summit in England.[note 4][1][18][4] Horses worked the next section, about 1+1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) in length, descending gently for over 1⁄2 mile (0.8 km), and then for 1 mile (1.6 km) at the rate of 1 in 80 and 1 in 88. At the Park Head wheelhouse, the waggons were attached to a tail-rope and let down an incline at gradients of 1 in 80 and 1 in 82, 1+1⁄2 miles (2.4 km) in length, to a stationary engine at Meeting Slacks. Here the rope was changed, they continued their descent down a second incline 1+1⁄4 miles (2.0 km) in length; the steepest gradients were 1 in 35, 1 in 41 and 1 in 47. This brought the wagons to Waskerley.

Next the line descended down to the valley by means of a self-acting plane called Nanny Mayor's bank (or Nanny Mayer's bank); it was 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) long, with a gradient of 1 in 41. From the bottom of this incline, horses drew the wagons along the near-level past White Hall and Rowley (or Cold Rowley), then reaching the ravine at Hownes Gill where a break occurred in the line. The cleft at Hownes Gill is 800 feet (240 m) wide and 160 feet (49 m) deep, with steep rocky sides. When the line was planned, it was obvious that a viaduct was unaffordable and an alternative means of crossing was adopted. A track of with four rails, the outer pair at a gauge of 7 ft 1⁄8 in (2,137 mm) and the inner pair at 5 ft 1+3⁄4 in (1,568 mm), was laid down each face of the ravine, with gradients of 1 in 2+1⁄2 on the west side and 1 in 3 on the east. A special cradle was built for each side, with the lower wheels larger than the upper wheels, so as to keep the platform level. The wagons were run onto one of these cradles and were lowered to the bottom, where they were transferred to the other cradle for the ascent of the other side. The wagons travelled sideways-on. Both cradles worked simultaneously, driven by a 20-horsepower (15 kW) stationary engine situated at the bottom, the ascending and descending cradles partly balancing one another. Only one railway wagon could be handled in each direction at a time, limiting the throughput to twelve an hour.[1][4][6][19]

After Hownes Gill the line passed the site of Consett Iron Works, later very much enlarged and developed; the line climbed at 1 in 71 to Carr House. There the Medomsley colliery branch of the S&TR trailed in. From Carr House the line continued, falling at 1 in 108; both inclines were worked by a stationary engine at Carr House. The line then ran northeast along the ridge near the collieries of Stanley and Annfield Plain. It passed over the Pontop Ridge (between East Castle and Annfield) on an incline, gradient 1 in 148, worked by a stationary engine at the summit, at Loud Bank, then reaching Annfield. Here the Harelaw Waggonway, adopted by the S&TR as a branch, trailed in.

The gradients then fell further towards the east, descending by self-acting inclines consisting, from west to east, of the Stanley bank (maximum gradient 1 in 21), Twizell bank (1 in 17+1⁄2), Eden bank (1 in 17), and the Long Waldridge bank (1 in 20+1⁄2 to 1 in 24+1⁄2). The line then crossed the course of present-day East Coast main line, opened here in 1868, north of Chester-le-Street. This section was level enough for locomotive working, passing through Washington and Boldon, and near Brockley Whins to reach South Shields. Running at high level through the town, the line ended at quays off Wapping Street and Long Row.[1][6]

On 28 August 1839 the Sacriston waggonway opened; it ran from the colliery to the Waldridge waggonway, and together they formed a branch railway over 3 miles (5 km) in length. The Sacriston pit was to bring considerable traffic to the S&TR. It joined the S&TR at Pelton Fell.

On 11 November 1840 the Brandling Junction Railway opened its Tanfield Moor branch. This resulted immediately in Tanfield Moor traffic diverting away from the Stanhope and Tyne line.[4]

Incline working

The cost of working the self-acting inclines on the Stanhope and Tyne Railway in 1839 was £415 per mile; the inclines with stationary engines in the same period was about £485 per mile. Tomlinson, writing about the North Eastern Railway in 1903, said:

Sixty great ropes, of a total length of 68 miles [109 km], were daily travelling over these stationary engine and self-acting inclines at a speed of from 7 to 11 miles per hour [11 to 18 km/h] with loads of 24, 32, 48 and even 96 tons attached to them. Some of the earlier ones—those originally used on the Stanhope and Tyne Railway—were of india rubber solution, a material found to swell and become soft in wet weather, and therefore unfitted to stand the friction on the inclines. From 1835 to 1841 no other than hempen ropes were used and, as these were occasionally tarred, a smooth and glossy surface was soon formed upon them which diminished the wear from friction. Varying in girth from 4 to 8+1⁄8 inches [10 to 21 cm] and in weight from nearly 2 to 6 tons per mile, these ropes rarely lasted longer than 10 months—their average duration was 7 months... By means of these stationary engines it was possible to work over the principal inclines from 2,000 to 4,000 tons a day... The power of the "Vigo" engine was the measure of the carrying capacity of the Stanhope and Tyne Railway. In 1837, with waggons at both sides, it was capable of making 4 "runs" an hour with 24 waggons, equal to 1,158 waggons in a day of 12 hours.[20]

In January of each year the entire line was closed for a week so that the ropes could be changed and the machinery inspected; this coincided with colliery closures for corresponding reasons.[15]

The Brandling Junction Railway

In 1839 the Brandling Junction Railway opened much of its network. It was conceived to connect Gateshead and collieries nearby to Monkwearmouth, and its main line was on that axis. It also took over the Tanfield Waggonway. It intersected the S&TR at an oblique angle at Boldon Lane (the later site of Tyne Dock station) and at Brockley Whins near Boldon, where there was a square flat crossing (see Brockley Whins, below). It was desired to connect the two lines, and this was done by a loop line about 8 chains (160 m) in length, the cost of which was borne by the S&TR, the Brandling Junction Railway, and the Durham Junction Railway in equal proportions. This loop was opened on 9 March 1840, when the new service of trains was started, and passengers were carried for the first time over the Durham Junction Railway.

The Durham Junction Railway

On 16 June 1834 the Durham Junction Railway obtained its authorising act of Parliament, the Durham Junction Railway Act 1834 (4 & 5 Will. 4. c. lvii), to build a 7-mile (11 km) railway from collieries at Houghton-le-Spring to Washington where it joined the S&TR. The S&TR subscribed more than 50% of the share capital of the Durham Junction Railway: £40,000 of the £80,000 share capital.[15] An agreement had been made on 17 May 1834, that the line would be worked by the locomotives of the Stanhope and Tyne Railway Company.

In fact the company never progressed the line further south than Rainton Meadows.

Bankruptcy

At the end of 1840 the company was unable to pay its debts, and the loss of the Tanfield Moor traffic emphasised the difficulty. As it was a partnership the partners were each liable for the debt without limit. The authorised capital of the company was £150,000 and loans to the extent of £440,000 had been taken, in violation of the terms of the deeds of the company. It had closed the Stanhope to Carr House section to save money, although it was obliged to continue the rental of the quarry and the wayleave fees for the line.

On 29 December 1840 an extraordinary general meeting was held at which it was decided to promote a statutory company, with capital of £440,000, to take over the railway and its debts. On 5 February 1841 the Stanhope and Tyne Railroad Company was dissolved, and its assets and debts transferred to a new company.

The Pontop and South Shields Railway

| Stanhope and Tyne Railroad Company (Dissolution) Act 1842 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to facilitate Arrangements consequent upon the Dissolution of the Stanhope and Tyne Railroad Company, and to incorporate some of the Proprietors, for the Purpose of continuing the working of a Part of the Railway belonging to the said Company. |

| Citation | 5 & 6 Vict. c. xxvii |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 13 May 1842 |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

The new company was called the Pontop and South Shields Railway Company (P&SSR); it was incorporated by an act of Parliament, the Stanhope and Tyne Railroad Company (Dissolution) Act 1842 (5 & 6 Vict. c. xxvii), on 23 May 1842. The section of line between Stanhope and Consett (then called Carr House), and the limestone quarries at Stanhope, were sold to the Derwent Iron Company. The blast furnace method of iron production required considerable quantities of limestone.[1][6][10]

Taking over a loss-making railway was not a plan for easy success, and it was not until 1844 when the through route from London to Gateshead opened, using part of the P&SSR line, that the finances improved.[15]

Derwent Iron Company

Around the area of Carr House there were extensive deposits of iron ore as well as coal, and the availability from relatively near of abundant limestone encouraged consideration of iron smelting, and in 1840 Jonathan Richardson founded the Derwent Iron Company there. Within ten years the district had a population of 2,500 due to the iron works. When the Stanhope and Tyne Railway fell into financial difficulties, the Derwent Iron Company had to take urgent steps to ensure continuity of the Stanhope limestone, and it was this factor that caused the acquisition referred to above.[15]

The Derwent Iron Company sought to connect with the Stockton and Darlington Railway at Crook (near Bishop Auckland) and projected a railway from Waskerley on the section it had acquired from the Stanhope company. It arranged wayleaves for the purpose in 1843, and arranged with the Stockton and Darlington Railway for the latter to lease the line from Waskerley and the existing former section, which it reopened.[10] The Stockton and Darlington Railway took possession on 1 January 1845 and named the lines "the Wear and Derwent Junction Railway".[10] The line from Crook to Waskerley Junction was designed by John Harris and known as the Weardale Extension Railway, and it opened on 16 May 1845.[1][4] A passenger service was operated from Crook to Stanhope from 1 September 1845, but at the end of October 1845 it was cut back to run from Crook to Waskerley only. From 1 April 1846 it started running from Crook to Cold Rowley (later simply "Rowley"), reversing at Waskerley Junction. Continuation to the Carrhouse station at Consett was not feasible for passenger trains at the time because of the means of crossing the deep ravine and Hownes Gill on the intervening section.[1]

The Wear Valley Railway company had been established in July 1845, to extend the Bishop Auckland line from Witton-le-Wear to Frosterley, and in 1846 the Wear Valley Railway took possession of the Derwent Iron Company's lines taken from the Stanhope and Tyne. The Wear Valley Railway was still building its own line. A further act of Parliament, the Wear Valley Railway Act 1847 (10 & 11 Vict. c. ccxcii) confirmed the statutory position of those lines on 28 September 1847. The Wear Valley Railway was in effect a subsidiary of the Stockton and Darlington Railway, which worked the Derwent Iron Company section.

The rope-worked inclines leading north from Crawley to the Parkhead summit were on moderate gradients and the technical improvements in locomotive design enabled consideration of their use. A deviation over a distance of just over 1 mile (1.6 km) bypassed the inclines and located the line a little further down the hillside. This enabled elimination of the rope-working and was inaugurated in 1847. It was done without Parliamentary authorisation.[6][10][21]

The Stockton and Darlington Railway took direct control of the numerous subsidiary companies in 1858 and on 3 September 1858 ownership of the Derwent Iron Company section was transferred to the Stockton and Darlington Railway.[4]

Brockley Whins

When the Brandling Junction Railway main line was constructed in 1839 it crossed the S&TR near Boldon by a flat crossing, with a west-to-north connection curve and a south-to-east curve. In the following years a number of local railways were opened which together formed a through north-south route: the beginnings of an East Coast main line, although not the present-day route. In 1844 the final link in this chain (Belmont Junction to Rainton Crossing) was opened and on 24 May 1844 a special train carrying the directors of the Newcastle and Darlington Junction Railway ran through from York to Gateshead. On 18 June 1844 a special train was run from London to Gateshead, the journey lasting 9 hours 21 minutes, including 70 minutes of stoppage. The following day a public service was inaugurated. The trains ran over the Durham Junction Railway to Washington and then over the Pontop and South Shields line (former S&TR) to Boldon North Junction, reversing there and running over the Brandling Junction line via Brockley Whins.[note 5]

On 19 August 1844 a south-to-west curve was opened, avoiding the reversal. It had been constructed at the joint expense of the Pontop and South Shields and Brandling Junction companies. Although a short line it involved a crossing of a deep valley of the River Don, and a considerable wooden viaduct had had to be built. The structure was 217 feet (66 m) long and was 42 feet (13 m) above water level. It consisted of single timber trestles of various heights, about 20 feet (6 m) apart, on which were laid longitudinal beams and cross girders. Use of this route by main line trains continued until 1850, when the opening for passengers on 1 October 1850 of a line between Washington and Pelaw enabled trains to run by a more direct route.[22]

The Pontop and South Shields Railway

The Pontop and South Shields Railway, established in 1842, generated enough capital to pay off the bulk of the debt of the Stanhope and Tyne line, and continued operating as before, except for the Derwent Iron Company section southwest of Carr House.

In a series of changes of owning company, the Pontop and South Shields Railway was taken over by the York and Newcastle Railway on 1 January 1847. On 9 August 1847 that company enlarged and became the York, Newcastle and Berwick Railway and on 31 July 1854 the North Eastern Railway was formed from a merger of that company and others.

The North Eastern Railway acquired the Stockton and Darlington Railway in 1863 so that the whole of the former Stanhope and Tyne network was now in its possession.[1][4]

The Stockton and Darlington Railway at Consett

From about 1857 mineral traffic at Consett became very difficult to operate. The railways had been built to take heavy minerals from the area downhill to the Tyne and the coast, but now iron ore was being brought in from the Cleveland districts to the east, and from Whitehaven in the west, requiring a long uphill haul. As much of these routes was over rope-worked inclines, this was an expensive and slow business. In the case of the self-acting (gravity) inclines, locomotive assistance was brought in; in some cases to propel the loaded uphill set.

The Hownes Gill defile presented a major constraint on mineral and passenger traffic. Some relief was obtained from 1853 when it was found possible to run sets of three wagons down the very steep inclines and up the other side on their own wheels, but finished iron products on wagons were liable to shift on the descent. At length in December 1856 the Stockton and Darlington Railway (as interim operators of the line) decided to substitute a viaduct for the inclines; the viaduct was designed by Thomas Bouch. The viaduct of twelve arches was opened on 1 July 1858.[6] It was 730 feet (220 m) long and 150 feet (46 m) high.[4] It was one of the most spectacular viaducts in the Northeast England, constructed of firebrick with room for a single line.[23]

The Newcastle newspaper reported:

Opening of the Hownes Gill Viaduct on the Stockton and Darlington Railway: This structure was opened on Friday last [25 June, contradicting Tomlinson]... At half past 12 a train of 72 laden waggons was passed slowly over the bridge without the slightest signs of shake or deflection being observable. Afterwards a locomotive, appropriately termed "The Leader", repeated this experiment... During its progress [the work] has been unattended by any accident, and on its completion has been opened with complete success. The materials used are fire-bricks, manufactured at Pease's and Stobart's works, and stones of the finest quality, hewn from an adjoining quarry—of which there are 3+1⁄2 millions of the former, and 100,000 cubic feet [2,800 m3] of the latter. The entire length of the viaduct is 700 feet [210 m], its height 175 feet [53 m], with 12 arches of 50 feet [15 m] span each. Fifteen months have sufficed for its erection, at a cost of £14,000, for a single line of way. It is 45 feet [14 m] higher than the High Level Bridge.[24]

The reversal at Waskerley Junction was obviously inconvenient, particularly for through mineral traffic between Crook and Consett, and on 4 July 1859, the S&DR opened the Waskerley deviation, a line from Burnhill junction making a gradual but continuous descent to Whitehall junction, forming the third side of a triangle. Locomotive working was now possible from Crook to Carr House. The old line between Waskerley Junction and Whitehall Junction, including Nanny Mayor's incline, was then abandoned.[4][6]

Improving the line

The P&SSR itself ordered improvements to its own line about the same time; from Stella Gill (Pelton Fell) to Fatfield (east of Vigo) was doubled; the new work was opened on 8 June 1857. Vigo had been a rope-worked incline, albeit of moderate gradient, and on the completion of the doubling work the rope working was abolished, and locomotive working substituted. The level crossing of the Durham Turnpike (the Great North Road) was altered to cross the road by a bridge.[15]

The numerous rope worked inclines were a continuing inconvenience and source of expense, and in 1875 the North Eastern Railway obtained authorisation to bypass some of them by new routes on easier gradients. That scheme was dropped, but on 19 June 1882 the powers were renewed on a modified scheme. A deviation line looping south of the hills near Annfield Plain that had necessitated Loud Bank incline, was opened on 1 January 1886.[6]

This left three difficult inclines between Annfield Plain and Pelton, where the line crossed the East Coast Main Line (ECML). The North Eastern Railway decided to build a completely new line 6+1⁄2 miles (10.5 km) long, suitable for locomotive operation; the new line was to make a junction with the ECML, and to connect the old Stanhope line there as well. This scheme was authorised on 23 May 1887 and the connection from the old line to the ECML was opened 16 October 1893. The new deviation line, known as the Annfield Plain Branch, was opened on 13 November 1893. In both cases the openings were for mineral trains only; passenger opening for the Annfield Plain Branch followed on 17 August 1896.[4] There were numerous colliery connections on the old line, which was retained to serve them. The Edenhill and Stanley inclines became disused in 1946 but the Waldridge incline continued in operation serving collieries on Pelton Level until the late 1960s.

The Annfield Plain Branch naturally had stiff gradients and in the 1960s it became notable for the operation of the Tyne Dock to Consett iron ore trains, operated by two class 9F 2-10-0 locomotives climbing the 1 in 50 gradients.[4]

Chronology of connecting lines

Stanhope and Tyne Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Running west to east across what became a fruitful mining area, the line attracted a considerable number of connecting railways.

The line west of Parkhead sand quarry closed on 28 April 1951.[10]

The Weatherhill and Rookhope Railway opened in 1846; it was a private line built by the Weardale Iron and Coal Company (WICC), trailing in to the S&TR at Weatherhill. The line is alternatively known as the Weardale Iron and Coal Company Railway. It was built without Parliamentary authority. It left the S&TR line at Parkhead and turned north, climbing into the hills to Bolts Law, where limestone, iron and lead were extracted. The summit near Bolts Law was at 1,670 feet (510 m) above sea level [note 6][10][18] There was an inclined plane 2,000 yards (1.8 km) long with gradients of 1 in 12 and 1 in 6 descending from Bolts Law engine to Rookhope. Locomotives were in use on the Parkhead side of the incline. From Rookhope the line turned south climbing the flank of the hill on the west side of the Rookhope Burn, then climbing to 1,300 feet (400 m) on the Bishop's Seat incline, turning west and running parallel to the River Wear but high above it, as far as Scutterhill, above Westgate.

About 1860 a northward branch from Rookhope was opened to reach the massive Rookhope lead smelter.

Bishops Seat incline was self-acting although an engine house seems to have been provided initially.

The railway was also known as Weardale Iron Company Railways, the Weatherhill and Rookhope Railway and the Rookhope and Middlehope Railway. The system beyond Slithill closed in 1905, and the remainder closed on 15 May 1923. However a twice weekly horse drawn "train" took supplies up the closed line to Bolts Law cottages for some years. The line was taken up during World War II.[10]

At Waskerley Park the line to Crook diverged; it opened in 1845 and closed in 1968. The section of the S&TR from that junction to Whitehall Junction closed in 1859. At Whitehall Junction the Stockton and Darlington Railway line from Crook trailed in; it opened in 1859 and closed in 1969.

From Whitehall Junction to the junctions at Consett closed in 1969. At Hownes Gill Junction the line towards the Rowlands Gill line diverged, forming a triangle with Consett East Junction. There were numerous connections to the iron works here. The Rowlands Gill line opened in 1867 and closed in 1982.

At Carr House the 1834 Medomsley Colliery branch trailed in; in 1839 the S&TR extended it northwards to Derwent Colliery;[15] this involved a further inclined plane; it closed in 1959.

South Medomsley Colliery had a branch which trailed in east of Leadgate, opening in 1864 and closing in 1953.

At East Castles Junction the 1886 deviation line diverged right; the original S&TR line closed at the western end but the eastern end had numerous colliery connections and remained in use; the Harelaw branch trailed in to the original line near Annfield, giving access from Whiteleahead from 1834, and later from Lintz Colliery (1858); it closed in 1947 except for a stub at Harelaw goods, which closed in 1980. The original line and the deviation converged at Annfield Plain Junction.

At Annfield Plain Junction the 1893 deviation diverged left; the original line continued through Stanley, where there were several pits; the Shieldrow Waggonway diverged left to serve that colliery. The original S&TR route remained open as far as Stanley Bank Top until 1961; beyond that point it closed in 1946. The deviation line itself closed in 1985.

From Stanley Bank Top the line descended past the Gate Pit of Twizell Colliery then descending Edenhill Bank to Pelton Level, where the short Handenhold waggonway converged from the left, serving a colliery and quarry, and the important Craghead Waggonway converged from the right. As well as West Pelton colliery this brought in traffic from the Burnhope Waggonway.

The line continued to Pelton Fell, where there were important colliery workings, and where the Waldridge Waggonway converged from the right. This was extended in 1839 to Sacriston to serve expanding collieries there.[15]

There was a curve near Chester-le-Street facing from the S&TR to the East Coast Main Line (opened in 1868) northwards; the connection opened in 1893 and closed in 1985. From that point the line ascended and then descended moderate inclines with a summit at Vigo. At Washington South Junction the Durham Junction Railway converged, opening in 1838 and closing in 1991. From there the short section of the S&TR as far as Washington, where the York Newcastle and Berwick Railway (the "Leamside Line") diverged left. It remained open until the same year, but from Washington the S&TR closed in 1968.

At Southwick Junction the Hylton, Southwick and Monkwearmouth Railway diverged right, opening in 1876 and closing in 1926.

From Boldon to the former Brockley Whins, the S&TR line remained open until 1967; at Hedworth Lane Junction a curve diverged right to the Brandling Junction Railway, opened in 1839 and closed in 1988; the joint P&SSR and Brandling Junction curve diverged right to the later Brockley Whins station; it opened in 1844 and closed in 1940. The west to north curve converging at the north junction opened in 1839 by the Brandling Junction and remains open; and the east to north curve, also still open, was opened by British Railways in 1965. The line from here to South Shields remains open for freight purposes, paralleling the Metro system.

At Harton Junction the Brandling Junction route from Monkwearmouth, opened in 1839, converged from the right; it closed in 1965; the Brandling Junction independent route to the Tyne diverged left, opening at the same date and closed in 1981.[10][15][21]

After 1923

On 1 January 1923 the main line railways of Great Britain were "grouped" following the Railways Act 1921. The North Eastern Railway was a constituent of the new London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). In 1948 the companies were nationalised.

In 1940 the condition of the timber viaduct over the Don on the Brockley Whins curve was giving rise to concern and the decision was taken to demolish it and close the line.[25]

Regular passenger services on the S&TR network ceased on 23 May 1955,[26] and the line was closed in the early 1980s,[27] with much of the track having been lifted by 1985.

Preservation and paths

Both parts of the former line are now mainly used as foot and cycle paths, with part incorporated into the national Sustrans system. Part of the Consett to Sunderland section of the line has been used as the 42-kilometre (26 mi) Consett and Sunderland Railway Path which runs from Lydgett's Junction, Consett in the west to Roker beach, Sunderland[28][29][30] and the section from Stanhope to Consett is now the 16-kilometre (9.9 mi) Waskerley Way public footpath.[31][32]

The 1833 winding engine of the Weatherhill Incline is on display in the National Railway Museum, York.

In January 2019, Campaign for Better Transport released a report identifying the line between Consett and Washington which was listed as Priority 2 for reopening. Priority 2 is for those lines which require further development or a change in circumstances (such as housing developments).[33]

Topography

The Stanhope and Tyne Railway was never planned for passenger operation, and when this took place it was in many cases informal, provided for miners on coal trains. Some early "stations" had no facilities whatever, and there was never a consistent through service from end to end of the line.

From Stanhope the principal locations were:

- Stanhope quarries;

- Crawley; opened 1 September 1845; closed 31 October 1845; reopened 1 April 1846; closed after December 1846;

- Waskerley; opened 1 September 1845; closed 4 July 1858;

- Waskerley Junction; line to Crook diverged;

- Whitehill Junction; line from Crook converged;

- Rowley; opened 1 September 1845; renamed Rowley 1868; closed 1 May 1939;

- Consett; opened 1 September 1862; replaced by another station opened as Benfieldside 2 December 1867;

- Carrhouse; opened 1 July 1858; closed 1 October 1868;

- Leadgate; opened 17 August 1896; closed 23 May 1955;

- Pelton; opened by March 1862; closed after January 1869;

- Durham Turnpike; opened 16 April 1835; closed after December 1853; reopened by March 1862, closed after January 1869;

- Vigo; opened 16 April 1835; closed after December 1853; reopened from March 1862; closed after January 1869;

- Biddick Lane; opened February 1864; closed after January 1869;

- Washington; opened 16 April 1835; closed after December 1853;

- Jarrow; opened by August 1844;

- South Shields; opened 16 April 1835; closed 19 August 1844, when the service was diverted to the Brandling Junction "Low" station. However, in 1879 the NER built a new station on the site of this S&TR station and all services were diverted to here. It remained open until 1981 when it was replaced by a Tyne & Wear Metro station around 150 m (160 yd) further south, which approached it on the S&TR line from Tyne Dock. In 2019, a new Metro station will replace the 1980s one, again around 100 m (110 yd) further south;

- South Shields quays.[21][34]

Notes

- ^ Landsale pit: one whose output was expected to be sold locally and not shipped away from the district.

- ^ According to Snaith and Lee; Hoole says "the old Pontop Waggonway". Tomlinson says (page 212) "probably down the old Pontop waggonway."

- ^ Tomlinson refers, on page 243, to a summit at Whiteleahead, 1,445 feet (440 m) above the sea. Whiteley Head is nearby, and is not to be confused with White-le-Head or Whiteley Head at the end of the North Eastern Railway Tanfield Branch.

- ^ Several sources make this assertion; the nearby Weatherhill and Rookhope Railway crossed the 1,600-foot (490 m) contour, but that was not a public railway.

- ^ The names of the junctions have changed over time. The area was referred to as Brockley Whins and most sources refer to the reversal taking place at Brockley Whins. A station of that name was later built to the west, and as it was a simple through station, no reversal was required there.

- ^ From Bell, page 154; he offers the conversion to 536 metres, but the correct figure is 509 metres. The Boltslaw Engine was at 515 metres.

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l A F Snaith and Charles E Lee, The Stanhope & Tyne Railway: 1 — History and Description, in Railway Magazine, July and August 1942

- ^ Gordon Biddle. The Railway Surveyors, Ian Allan Limited, Shepperton, 1990, ISBN 0 7110 1954 1

- ^ M J T Lewis, Early Wooden Railways, Routledge and Kegan Paul, London, 1974, ISBN 0 7100 7818 8

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n K Hoole, A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain: volume 4: The North East, David and Charles, Dawlish, 1965

- ^ "A valuable sea-sale and land-sale colliery to be let". Newcastle Courant. 5 February 1831. Retrieved 13 April 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l William Weaver Tomlinson, The North Eastern Railway: Its Rise and Development, Andrew Reid and Company, 1915

- ^ On 1 May; Tomlinson, page 241

- ^ "The first locomotive engine was placed on the Stanhope and Tyne Railway at South Shields on Thursday afternoon". Newcastle Courant. 10 May 1834. Retrieved 17 April 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The first locomotive engine was placed on the Stanhope and Tyne Railway at South Shields on Friday last". Durham County Advertiser. 9 May 1834. Retrieved 17 April 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Dr Tom Bell, Railways of the North Pennines, The History Press, Stroud, 2015, ISBN 978-0-7509-6095-3

- ^ "Opening of the Stanhope and Tyne Railway". Newcastle Journal. 17 May 1834. Retrieved 17 April 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Hoole, page 188

- ^ "Opening of the Stanhope and Tyne Railway". Newcastle Journal. 13 September 1834. Retrieved 17 April 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Tomlinson, page 248

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k G F Whittle, The Railways of Consett and North-West Durham, David and Charles, Newton Abbot, 1971, ISBN 0 7153 5347 0

- ^ Tomlinson, pages 392 and 393

- ^ Tomlinson, pages 366 and 367

- ^ a b History of Railways in Durham, https://sites.google.com/site/waggonways/history-durham

- ^ A B Granville, The Spas of England I: Northern Spas, Henry Colburn, London, 1841, pages 309-311

- ^ Tomlinson, pages 379 to 381

- ^ a b c Col M H Cobb, The Railways of Great Britain—A Historical Atlas, Ian Allan Publishing Limited, Shepperton, 2003, ISBN 07110 3003 0

- ^ Demolition of Brockley Whins Viaduct, in Railway Magazine, February 1941

- ^ M F Barbey, Civil Engineering Heritage: Northern England, Thomas Telford, London, 1981, ISBN 0 7277 0357 9

- ^ "Opening of the Hownes Gill Viaduct of the Stockton and Darlington Railway". Newcastle Courant. 2 July 1858. Retrieved 17 April 2016 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Railway Magazine, February 1941

- ^ R V J Butt, The Directory of Railway Stations, Patrick Stephens Ltd., Yeovil, 1995, ISBN 1-85260-508-1

- ^ Cecil J Allen, The North Eastern Railway, Ian Allan, Shepperton, 1964, ISBN 0-7110-0495-1

- ^ "Consett and Sunderland Railway Path". Long Distance Walkers Association.

- ^ "Consett to Sunderland | Britain's best bike rides". The Guardian. 4 May 2012. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ "Consett and Sunderland Railway Path". Sustrans. Retrieved 5 January 2023.

- ^ "Waskerley Way Railway Path" (PDF). Durham County Council.

- ^ "Waskerley Way". Long Distance Walkers Association.

- ^ [1] p.42

- ^ M E Quick, Railway Passenger Stations in England Scotland and Wales—A Chronology, The Railway and Canal Historical Society, 2002

Further reading

- Richardson, M.A. (1844). "10 September 1834". The local historian's table book of remarkable occurrences, historical facts, traditions, legendary and descriptive ballads &c., &c. connected with the counties of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Northumberland, and Durham. Vol. 4. p. 210.

- Harrison, T. E. (1838). "Description of the Drops Used by the Stanhope and Tyne Railroad Company for the Shipment of Coals at South Shields. (Including Plates.)". ICE Transactions. 2: 69–71. doi:10.1680/itrcs.1838.24386.

- Langham, Rob (2020) The Stanhope & Tyne Railroad Company, Amberley, ISBN 978-1445697666

External links

- "Pontop and South Shields Railway Company (RAIL 569)". The National Archives.

- Historic England. "Stanhope and Tyne railway (1376130)". Research records (formerly PastScape).

- Lambeth, Roy. "Stanhope & Tyne Railway". disused-stations.org.uk.

- "Stanhope and Tyne Railway". railbrit.co.uk., Map showing track