Sportsman's Park

c. 1961 | |

| |

| Former names |

|

|---|---|

| Location | Sullivan Ave. 3623 Dodier St. (Cardinals) & 2911 N Grand Blvd (Browns). St Louis, Missouri, U.S.[1] |

| Coordinates | 38°39′29″N 90°13′12″W / 38.658°N 90.220°W |

| Owner | St. Louis Cardinals (1953–1966) St. Louis Browns (1902–1953) |

| Operator | St. Louis Cardinals (1953–1966) St. Louis Browns (1902–1953) |

| Capacity |

|

| Field size | Left Field: 351 ft (107 m) Left-Center: 379 ft (116 m) Deepest corner (just left of dead center): 426 ft (130 m) Deepest corner (just right of dead center): 422 ft (129 m) Right-Center: 354 ft (108 m) Right Field: 310 ft (94 m) Backstop: 68 ft (21 m) |

| Surface | Natural grass |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | 1880 |

| Opened | April 23, 1902[1] |

| Renovated | 1909[1] |

| Expanded | 1909 1922 1926 |

| Closed | May 8, 1966 |

| Demolished | 1966 |

| Construction cost | US$300,000 ($10.6 million in 2023 dollars[2]) $500,000 (1925 refurbishment) |

| Architect | Osborn Engineering Company |

| Tenants | |

| |

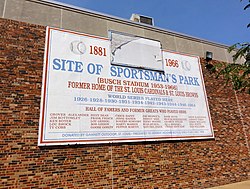

Sportsman's Park was the name of several former Major League Baseball ballpark structures in St. Louis, Missouri. All but one of these were located on the same piece of land, at the northwest corner of Grand Boulevard and Dodier Street, on the north side of the city.

History

Sportsman's Park was the home field of both the St. Louis Browns of the American League, and the St. Louis Cardinals of the National League from 1920 to 1953, when the Browns relocated to Baltimore and were rebranded as the Orioles.

The physical street address was 2911 North Grand Boulevard. The ballpark (by then known as Busch Stadium, but still commonly called Sportsman's Park) was also the home to professional football: in 1923, it hosted St. Louis' first NFL team, the All-Stars, and later hosted the St. Louis Cardinals of the National Football League from 1960 (following the team's relocation from Chicago) until 1965, with Busch Memorial Stadium opening its doors in 1966.

1881 structure

Baseball was played on the Sportsman's Park site as early as 1867. The tract was acquired in 1866 by August Solari, who began staging games there the following year. It was the home of the St. Louis Brown Stockings in the National Association and the National League from 1875 to 1877.

It was originally called the Grand Avenue Ball Grounds: some sources say the field was renamed Sportsman's Park in 1876, although local papers were not using that name until 1881, and some local papers used the alternate name "Grand Avenue Park" until at least 1885. The first grandstand, one of three on the site, was built in 1881. At that time, the diamond and the grandstands were on the southeast corner of the block, for the convenience of fans arriving from Grand Avenue. The park was leased[3] by the then-major American Association entry, the St. Louis "Brown Stockings", or "Browns". The Browns were a very strong team in the mid-1880s, but their success waned.

When the National League absorbed the strongest of the old Association teams in 1892, the Browns were brought along. Soon they went looking for a new ballpark, finding a site just a few blocks northwest of the old one, and calling it New Sportsman's Park, which was later renamed Robison Field. They also changed team colors from Brown to Cardinal Red, thus acquiring a new nickname, and leaving their previous team colors as well as the old ballpark site available.

After a fire at the Cardinals' ballpark on May 4, 1901, the club arranged to play some games at the original Sportsman's Park, which by then was being called "Athletic Park" and had only minimal seating. After a May 5 game, it was clear that the old park would no longer be a workable option: the team played on the road for a month while their own park was being rebuilt.

1902 and 1909 structures

When the American League Milwaukee Brewers moved to St. Louis in 1902 and took the Browns name, they built a new version of Sportsman's Park. They initially placed the diamond and the main stand at the northwest corner of the block.

This Sportsman's Park saw football history made: it became both the practice field and home field for Saint Louis University football teams, coached by the visionary Eddie Cochems, father of the forward pass. Although the first legal forward pass was thrown by Saint Louis' Bradbury Robinson in a road game at Carroll College in September 1906, Sportsman's Park was the scene of memorable displays of what Cochems called his "air attack" that season. These included a 39–0 thrashing of Iowa before a crowd of 12,000[4] and a 34–2 trouncing of Kansas witnessed by some 7,000.[5] Robinson launched an amazingly long pass in the game against the Jayhawks, which was variously reported to have traveled 48, 67 or 87 yards in the air. College Football Hall of Fame coach David M. Nelson[6] called the pass extraordinary, "considering the size, shape and weight" of the fat, rugby-style ball used at that time. Sports historian John Sayle Watterson[7] agreed. In his book, College Football: History, Spectacle, Controversy, Watterson described Robinson's long pass as "truly a breathtaking achievement". St. Louis finished with an 11–0 record in 1906, outscoring its opponents 407–11.

In 1909, the Browns moved the diamond to its final location, at the southwest corner, in the shadow of a new steel and concrete grandstand, the third such stadium in the major leagues, and the second in the American League (after Shibe Park).

The previous wooden grandstand was retained as left-field bleachers for a while, but was soon replaced with permanent bleachers. The Cardinals came back to their original home in mid-1920, as tenants of the Browns, after abandoning the outdated and mostly-wooden Robison Field.

After nearly winning the American League pennant in 1922, Browns owner Phil Ball confidently predicted that there would be a World Series in Sportsman's Park by 1926: in anticipation, he increased the capacity of his ballpark from 18,000 to 30,000. There was a World Series in Sportsman's Park in 1926—but it was the Cardinals, not the Browns, who took part in it, with the Cardinals upsetting the Yankees in a memorable seventh game.

Although the Browns had been the stronger team in the city for the first quarter of the century, they had never been quite good enough to win a pennant: after the previously weak Cardinals had moved in, the two teams' situations had started to reverse, both on and off the field. The Cardinals' 1926 World Series victory more or less permanently tipped the balance in their favor, and from then on, the Cardinals were clearly St. Louis' favorite team, though still tenants of the Browns. The 1944 World Series between the Cardinals and the Browns, won by the Cardinals by four games to two, was perhaps a good metaphor for the two clubs' respective situations: it remains the last World Series to be played entirely in one stadium as the home venue for both competing clubs, with the exception of the neutral-site play in the 2020 World Series.

In addition to its primary use as a baseball stadium, Sportsman's Park also hosted several soccer events. These included several in the St. Louis Soccer League, and the 1948 National Challenge Cup when St. Louis Simpkins-Ford defeated Brookhattan for the national soccer championship.

In 1936, Browns owner Phil Ball died. His family sold the Browns to businessman Donald Lee Barnes, but the Ball estate maintained ownership of Sportsman's Park until 1946, when it was sold to the Browns for an estimated price of over US$1 million.[8]

1953 sale

By the early 1950s, it was clear that St. Louis could not support both teams. Bill Veeck, owner of the Browns (who at one point lived with his family in an apartment under the park's stands),[9] fancied that he could drive the Cardinals out of town through his promotional skills. However, Veeck caught an unlucky break when the Cardinals' owner, Fred Saigh, pleaded no contest to tax evasion. Faced with certain banishment from baseball, Saigh sold the Cardinals to Anheuser-Busch in February 1953.[10][11] Veeck soon realized that the Cardinals now had more resources at their disposal than he could ever hope to match. Reluctantly, he concluded he was finished in St. Louis, and had no other option but to move the Browns.

As a first step, he sold Sportsman's Park to the Cardinals for $800,000.[12][13][14] Busch immediately renovated the stadium, which had not been well maintained in some time. Even with the rent from the Cardinals, the Browns had not been bringing in nearly enough revenue to bring the park up to code, with city officials even threatening to have the park condemned. Before the start of the next season, the Browns relocated to Baltimore and were rebranded as the Orioles.

The brewery originally wanted to name the ballpark Budweiser Stadium.[15] Commissioner Ford Frick vetoed the name because of public relations concerns over naming a ballpark after a brand of beer. However, the commissioner could not stop Anheuser-Busch president August Busch, Jr. from renaming it after himself, so the park was renamed Busch Stadium. However, many fans still called it by the old name. The Anheuser-Busch "eagle" model that sat atop the left field scoreboard flapped its wings after a Cardinal home run.[9] The next year, Anheuser-Busch introduced a new economy lager branded as "Busch Bavarian Beer", thus gaming Frick's ruling and allowing the ballpark's name to be branded by what would eventually be Anheuser-Busch's second most popular beer brand.[16]

Sportsman's Park / Busch Stadium was the site of a number of World Series contests, first way back in the mid-1880s, and then in the modern era. The 1964 Series was particularly memorable, the park's last, and featured brother against brother, Ken Boyer of the Cardinals and Clete Boyer of the Yankees. The Cardinals' triumph in seven games led to Yankees management replacing Yogi Berra with the Cardinals' ex-manager Johnny Keane (he had resigned after winning the Series), an arrangement which lasted only to early 1966. Both Series managers were St. Louis natives, but neither had ever played for the Cardinals. The stadium also hosted Major League Baseball All-Star Games in 1940, 1948, and 1957.

Replacement

Despite Busch's extensive renovations, it soon became apparent that Sportsman's Park was at the end of its useful life.

Parking at the stadium was almost non-existent. Its concrete-and-steel incarnation had been built only a year after the Model T was introduced, and the park had been designed in an era when fans took the trolley to games, meaning it was ill-suited to automobile access. Additionally, the neighborhood around the park had an increase in crime and dereliction starting in the late 1940s. In 1964, a Cardinals fan making his way to the home opener was shot and killed during an armed robbery.[16]

Sportsman's Park/Busch Stadium was replaced early in the 1966 season by Busch Memorial Stadium, during which time much was made of baseball having been played on the old site for more than a century. A helicopter carried home plate to Busch Memorial Stadium after the final game at Sportsman's Park on May 8, 1966.[9][17] The 1966 stadium was replaced forty years later by the new Busch Stadium in April 2006.[18]

Donated by August Busch, the Sportsman's Park site became home to the Herbert Hoover Boys Club,[19][20] which is now Boys & Girls Clubs of Greater St. Louis. While the grandstand was torn down 58 years ago, the diamond was still intact at the time the structures were cleared, and the field is now used for other sports.

Dimensions

For a small park, there were plenty of posted distance markers. The final major remodeling was done in 1926. Distance markers had appeared by the 1940s:[1]

| Dimension | Distance | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Left Field Line | 351 ft (107 m) | |

| Medium Left Center | 358 ft (109 m) | |

| True Left Center | 379 ft (116 m) | |

| Deep Left Center | 400 ft (122 m) | |

| Deep Left Center Field Corner | 426 ft (130 m) | The distance usually given for center field (sign later painted over) |

| Just to right of Deep Left Center Field Corner | 425 ft (130 m) | |

| True Center Field | 422 ft (129 m) | Just to left of Deep Right Center Field Corner |

| Deep Right Center Field Corner | Also 422 ft (129 m) | Almost true center field (sign later painted over) |

| Deep Right Center | 405 ft (123 m) | |

| True Right Center | 354 ft (108 m) | |

| Medium Right Center | 322 ft (98 m) | |

| Right Field Line | 310 ft (94 m) | |

| Backstop | 68 ft (21 m) |

The following links provide images of the field's markers.

- Photo of left field markers

- Photo of center and right center field markers

- Photo of right field markers

The diamond was conventionally aligned east-northeast (home plate to center field),[21][22] and the elevation of the field was approximately 500 feet (150 m) above sea level.[21]

Layout

The left field and right field walls ran toward center, roughly perpendicular to the foul lines or at right angles to each other. The center field area was a short diagonal segment connecting the two longer walls. When distance markers were first posted, there was a 426 marker at the left corner of that segment, and a 422 marker at the right corner of it. There was another 422 marker a few feet to the left of the other one, and that marked "true" center field. For symmetry, a corresponding marker (425) was set a few feet to the right of the 426. The two corner markers were eventually painted over, leaving just the 425 and the true centerfield 422. [1]

Gallery

- Artist's conception in 1875

- Before opening day in 1902

- New stands for 1909; previous main stand has become left field seating

- Sanborn map showing new stands.jpg

See also

References

- ^ a b c d Ballparks.com – Sportsman's Park

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Hetrick, J. Thomas (1999). Chris Von der Ahe and the St. Louis Browns. Lanham, Maryland.: Scarecrow. p. 151. ISBN 0-8108-3473-1.

- ^ "First Touchdown Is Scored After Few Minutes of Play", St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 30, 1906

- ^ "St. Louis U. Scores 12 Points in First Half of Great Game with Kansas", St. Louis Star-Chronicle, November 3, 1906

- ^ Nelson, David M.,The Anatomy of a Game: Football, the Rules, and the Men Who Made the Game, 1994

- ^ "The Johns Hopkins University Press webpage on John Sayle Watterson". Archived from the original on September 6, 2008. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ^ "Browns purchase Sportsman's Park". Milwaukee Journal. Associated Press. October 3, 1946. p. 8, part 2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b c Lowry, Philip (2006). Green Cathedrals. Walker & Company. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-8027-1608-8.

- ^ "Cardinals purchased by brewery $3,750,000". Spokane Daily Chronicle. Spokane, Washington. Associated Press. February 20, 1953. p. 11.

- ^ "Cards sold to St. Louis brewery". Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. February 21, 1953. p. 3, part 2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cards buy Sportsman's Park for $800,000, 'save' Browns". Milwaukee Sentinel. Associated Press. April 10, 1953. p. 2, part 2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Cards buy Sportsman's Park from Browns in $800,000 transaction". The Day. New London, Connecticut. Associated Press. April 10, 1953. p. 15.

- ^ "Beer company plans to deal baseball's Cardinals". Lodi News-Sentinel. Associated Press. October 26, 1995. p. 13.

- ^ "Budweiser tag given baseball park in St. Louis". Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. United Press. April 10, 1953. p. 8.

- ^ a b Ferkovich, Scott. "Sportsman's Park (St. Louis)". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved January 15, 2018.

- ^ "Giants win 8th in a row". Milwaukee Sentinel. UPI. May 9, 1966. p. 2, part 2.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Haudricourt, Tom (April 11, 2006). "Same name, fresh look". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. p. 5C.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Temple, Wick (January 30, 1966). "Old stadium due change this year". Tuscaloosa News. Alabama. Associated Press. p. 15.

- ^ "Sportsman Park is alive, although Cards have gone". Tuscaloosa News. Alabama. Associated Press. May 9, 1976. p. 11B.

- ^ a b "38.658 N, 90.220 W". Historic Aerials. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

- ^ "Objectives of the Game – rule 1.04". Major League Baseball. Retrieved January 9, 2016.

Further reading

- Green Cathedrals, by Philip J. Lowry

- Ballparks of North America, by Michael Benson

- St. Louis' Big League Ballparks, by Joan M. Thomas

- The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs, by Bill Jenkinson

- Dimensions drawn from baseball annuals.

External links

- "Sportsman's Park photographs". University of Missouri–St. Louis. (also available published via Flickr)

- KETC – Living St. Louis – Sportsman's Park 8:42 minutes of video, footage of Sportsman's Park in b&w and color and interviews assembled by local PBS station KETC

- Photos of Sportsman's Park: http://www.digitalballparks.com/National/Sportsmans.html

- Library of Congress map collection, Pictorial St. Louis, 1875, showing artist's conception of the ballpark

- Discussion of team uniforms for 1884, with team photos showing the ballpark