Spinal fusion

| Spinal fusion | |

|---|---|

Fusion of L5 and S1 | |

| Other names | Spondylosyndesis |

| Specialty | Orthopedics, neurology |

| ICD-10-PCS | M43.2 |

| ICD-9-CM | 81.0 |

| MeSH | D013123 |

| MedlinePlus | 002968 |

Spinal fusion, also called spondylodesis or spondylosyndesis, is a surgery performed by orthopaedic surgeons or neurosurgeons that joins two or more vertebrae.[1] This procedure can be performed at any level in the spine (cervical, thoracic, lumbar, or sacral) and prevents any movement between the fused vertebrae. There are many types of spinal fusion and each technique involves using bone grafting—either from the patient (autograft), donor (allograft), or artificial bone substitutes—to help the bones heal together.[2] Additional hardware (screws, plates, or cages) is often used to hold the bones in place while the graft fuses the two vertebrae together. The placement of hardware can be guided by fluoroscopy, navigation systems, or robotics.

Spinal fusion is most commonly performed to relieve the pain and pressure from mechanical pain of the vertebrae or on the spinal cord that results when a disc (cartilage between two vertebrae) wears out (degenerative disc disease).[3] It is also used as a backup procedure for total disc replacement surgery (intervertebral disc arthroplasty), in case patient anatomy prevents replacement of the disc. Other common pathological conditions that are treated by spinal fusion include spinal stenosis, spondylolisthesis, spondylosis, spinal fractures, scoliosis, and kyphosis.[3]

Like any surgery, complications may include infection, blood loss, and nerve damage.[4] Fusion also changes the normal motion of the spine and results in more stress on the vertebrae above and below the fused segments. As a result, long-term complications include degeneration at these adjacent spine segments.[2]

Medical uses

Spinal fusion can be used to treat a variety of conditions affecting any level of the spine—lumbar, cervical and thoracic. In general, spinal fusion is performed to decompress and stabilize the spine.[4] The greatest benefit appears to be in spondylolisthesis, while evidence is weaker for spinal stenosis.[5]

The most common cause of pressure on the spinal cord/nerves is degenerative disc disease.[6] Other common causes include disc herniation, spinal stenosis, trauma, and spinal tumors.[4] Spinal stenosis results from bony growths (osteophytes) or thickened ligaments that cause narrowing of the spinal canal over time.[4] This causes leg pain with increased activity, a condition called neurogenic claudication.[4] Pressure on the nerves as they exit the spinal cord (radiculopathy) causes pain in the area where the nerves originated (leg for lumbar pathology, arm for cervical pathology).[4] In severe cases, this pressure can cause neurologic deficits, like numbness, tingling, bowel/bladder dysfunction, and paralysis.[4]

Lumbar and cervical spinal fusions are more commonly performed than thoracic fusions.[6] Degeneration happens more frequently at these levels due to increased motion and stress.[6] The thoracic spine is more immobile, so most fusions are performed due to trauma or deformities like scoliosis, kyphosis, and lordosis.[4]

Conditions where spinal fusion may be considered include the following:

- Degenerative disc disease

- Spinal disc herniation

- Discogenic pain

- Spinal tumor

- Vertebral fracture

- Scoliosis

- Kyphosis (e. g., Scheuermann's disease)

- Lordosis

- Spondylolisthesis

- Spondylosis

- Posterior rami syndrome

- Other degenerative spinal conditions[4]

- Any condition that causes instability of the spine[4]

Contraindications

Bone morphogenetic protein (rhBMP) should not be routinely used in any type of anterior cervical spine fusion, such as with anterior cervical discectomy and fusion.[7] There are reports of this therapy causing soft tissue swelling, which in turn can cause life-threatening complications due to difficulty swallowing and pressure on the respiratory tract.[7]

Epidemiology

According to a report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), approximately 488,000 spinal fusions were performed during U.S. hospital stays in 2011 (a rate of 15.7 stays per 10,000 population), which accounted for 3.1% of all operating room procedures.[8] This was a 70 percent growth in procedures from 2001.[9] Lumbar fusions are the most common type of fusion performed ~ 210,000 per year. 24,000 thoracic fusions and 157,000 cervical fusions are performed each year.[6]

A 2008 analysis of spinal fusions in the United States reported the following characteristics:

- Average age for someone undergoing a spinal fusion was 54.2 years – 53.3 years for primary cervical fusions, 42.7 years for primary thoracic fusions, and 56.3 years for primary lumbar fusions [6]

- 45.5% of all spinal fusions were on men [6]

- 83.8% were white, 7.5% black, 5.1% Hispanic, 1.6% Asian or Pacific Islander, 0.4% Native American [6]

- Average length of hospital stay was 3.7 days – 2.7 days for primary cervical fusion, 8.5 days for primary thoracic fusion, and 3.9 days for primary lumbar fusion [6]

- In-hospital mortality was 0.25% [6]

Effectiveness

Although spinal fusion surgery is widely performed, there is limited evidence for its effectiveness for several common medical conditions. For example, in a randomized controlled trial of Swedish adults with spinal stenosis, after 2 and 5 years, there were no significant clinical benefits of lumbar fusion in combination with decompression surgery in comparison to decompression surgery alone. The study enrolled 247 patients from 2006 to 2012 and further found increased medical costs for those who received fusion surgery as a result of increased surgery time, hospital stay duration, and cost of the implant.[10]

Technique

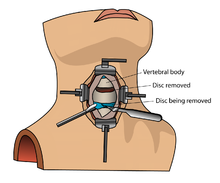

There are many types of spinal fusion techniques. Each technique varies depending on the level of the spine and the location of the compressed spinal cord/nerves.[4] After the spine is decompressed, bone graft or artificial bone substitute is packed between the vertebrae to help them heal together.[2] In general, fusions are done either on the anterior (stomach), posterior (back), or both sides of the spine.[4] Today, most fusions are supplemented with hardware (screws, plates, rods) because they have been shown to have higher union rates than non-instrumented fusions.[4] Minimally invasive techniques are also becoming more popular.[11] These techniques use advanced image guidance systems to insert rods/screws into the spine through smaller incisions, allowing for less muscle damage, blood loss, infections, pain, and length of stay in the hospital.[11] The following list gives examples of common types of fusion techniques performed at each level of the spine:

Cervical spine

- Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF)[4]

- Anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion[4]

- Posterior cervical decompression and fusion[4]

Thoracic spine

- Anterior decompression and fusion[4]

- Posterior instrumentation and fusion – many different types of hardware can be used to help fuse the thoracic spine including sublaminar wiring, pedicle and transverse process hooks, pedicle screw-rod systems, vertebral body plate systems.[4]

Lumbar spine

- Posterolateral fusion is a bone graft between the transverse processes in the back of the spine. These vertebrae are then fixed in place with screws or wire through the pedicles of each vertebra, attaching to a metal rod on each side of the vertebrae.

- Interbody Fusion is a graft where the entire intervertebral disc between vertebrae is removed and a bone graft is placed in the space between the vertebra. A plastic or titanium device may be placed between the vertebra to maintain spine alignment and disc height. The types of interbody fusion are:

- Anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF) – the disc is accessed from an anterior abdominal incision

- Posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF) – the disc is accessed from a posterior incision

- Transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) – the disc is accessed from a posterior incision on one side of the spine

- Transpsoas interbody fusion (DLIF or XLIF) – the disc is accessed from an incision through the psoas muscle on one side of the spine

- Oblique lateral lumbar interbody fusion (OLLIF) – the disc is accessed from an incision through the psoas muscle obliquely

Risks

Spinal fusion is a high risk surgery and complications can be serious, including death. In general, there is a higher risk of complications in older people with elevated body mass index (BMI), other medical problems, poor nutrition and nerve symptoms (numbness, weakness, bowel/bladder issues) before surgery.[4] Complications also depend on the type/extent of spinal fusion surgery performed. There are three main time periods where complications typically occur:

During surgery

- Patient positioning on operating table[4]

- Blood loss[4]

- Damage to nerves and surrounding structures during procedure[4]

- Insertion of spinal hardware[4]

- Harvesting of bone graft (if autograft is used)[4]

Within a few days

- Moderate to severe postoperative pain[12]

- Wound infections - risk factors include old age, obesity, diabetes, smoking, prior surgery[4]

- Deep vein thrombosis (DVT)[4]

- Pulmonary embolism (PE)[4]

- Urinary retention[4]

- Malnutrition[4]

- Neurologic deficit[4]

- Shock, sepsis and cerebrovascular infarction[13]

Weeks to years following surgery

- Infection – sources of bacterial bioburden that infiltrate the wound site are several, but the latest research highlights repeated reprocessing of implants before surgery and exposure of implants (such as pedicle screws) to bacterial contaminants in the "sterile-field" during surgery as major risk factors.[4][14][15][16][17][18]

- Deformity – loss of height, alignment, and failure of fusion[4]

- Pseudarthrosis – nonunion between fused bone segments. Risk factors include tobacco use, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, osteoporosis, revision procedures, decreased immune system.[4]

- Adjacent segment disease – degeneration of vertebrae above/below the fused segments due altered biomechanical stresses or patient propensity to develop progressive degenerative change.[19]

- Epidural fibrosis – scarring of the tissue that surrounds the spinal cord[4]

- Arachnoiditis – inflammation of the thin membrane surrounding the spinal cord, usually caused by infection or contrast dye.[4]

Recovery

Recovery following spinal fusion is extremely variable, depending on individual surgeon's preference and the type of procedure performed.[20] The average length of hospital stay for spinal fusions is 3.7 days.[6] Some patients can go home the same day if they undergo a simple cervical spinal fusion at an outpatient surgery center.[21] Minimally invasive surgeries are also significantly reducing the amount of time spent in the hospital.[21] Recovery typically involves both restriction of certain activities and rehabilitation training.[22][23] Restrictions following surgery largely depend on surgeon preference. A typical timeline for common restrictions after a lumbar fusion surgery are listed below:

- Walking – most people are out of bed and walking the day after surgery[22]

- Sitting – can begin at 1–6 weeks following surgery[22]

- Lifting – it is generally recommended to avoid lifting until 12 weeks[22]

- Driving – usually can begin at 3–6 weeks[22]

- Return to sedentary work – usually between 3–6 weeks[22]

- Return to manual work – between 7–12 weeks[22]

Rehabilitation after spinal fusion is not mandatory. There is some evidence that it improves functional status and low back pain so some surgeons may recommend it.[22]

Usage

According to a report by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), approximately 488,000 spinal fusions were performed during U.S. hospital stays in 2011, a rate of 15.7 stays per 10,000 population, which accounted for 3.1% of all operating room procedures.[8]

Public health hazard

In 2019, the news channel WTOL-TV broadcast an investigation, "Surgical implants raising contamination concerns", uncovering a dossier of scientific evidences that current methods of processing and handling spinal implants are extremely unhygienic and lacks quality control. This lack of quality control is exposing patients to high risk of infection, which themselves are underreported given the long time frame (0–7 years) and reportedly lack follow up data on the patients undergoing spine surgery. A petition was filed by the lead investigator, Aakash Agarwal, to rectify this global public health hazard of implanting contaminated spinal devices in patients.[24][25][26][27][28]

References

- ^ Meyer, Bernhard; Rauschmann, Michael (4 March 2019). Spine Surgery: A Case-Based Approach. Springer. ISBN 9783319988757.

- ^ a b c Chou, Roger (March 11, 2016). "Subacute and Chronic Low Back Pain: Surgical Treatment". UpToDate.

- ^ a b Rajaee, Sean (2012). "Spinal Fusion in the United States". Spine. 37 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1097/brs.0b013e31820cccfb. PMID 21311399. S2CID 22564134.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai Agulnick, Marc (2017). Orthopaedic Surgery Essentials: Spine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 343. ISBN 978-1-49631-854-1.

- ^ Yavin, D; Casha, S; Wiebe, S; Feasby, TE; Clark, C; Isaacs, A; Holroyd-Leduc, J; Hurlbert, RJ; Quan, H; Nataraj, A; Sutherland, GR; Jette, N (1 May 2017). "Lumbar Fusion for Degenerative Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Neurosurgery. 80 (5): 701–715. doi:10.1093/neuros/nyw162. PMID 28327997.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Rajaee, Sean S.; Bae, Hyun W.; Kanim, Linda E.A.; Delamarter, Rick B. (2012). "Spinal Fusion in the United States". Spine. 37 (1): 67–76. doi:10.1097/brs.0b013e31820cccfb. PMID 21311399. S2CID 22564134.

- ^ a b North American Spine Society (February 2013), "Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question", Choosing Wisely: an initiative of the ABIM Foundation, North American Spine Society, retrieved 25 March 2013, which cites

- Schultz, Daniel G. (July 1, 2008). "Public Health Notifications (Medical Devices)—FDA Public Health Notification: Life-threatening Complications Associated with Recombinant Human Bone Morphogenetic Protein in Cervical Spine Fusion". fda.gov. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- Woo, EJ (Oct 2012). "Recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2: adverse events reported to the Manufacturer and User Facility Device Experience database". The Spine Journal. 12 (10): 894–9. doi:10.1016/j.spinee.2012.09.052. PMID 23098616.

- ^ a b Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A, Andrews RM (February 2014). "Characteristics of Operating Room Procedures in U.S. Hospitals, 2011". HCUP Statistical Brief (170). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PMID 24716251.

- ^ Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A (March 2014). "Trends in Operating Room Procedures in U.S. Hospitals, 2001–2011". HCUP Statistical Brief (171). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PMID 24851286. Archived from the original on 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2014-05-19.

- ^ Försth, Peter; Ólafsson, Gylfi; Carlsson, Thomas; Frost, Anders; Borgström, Fredrik; Fritzell, Peter; Öhagen, Patrik; Michaëlsson, Karl; Sandén, Bengt (2016-04-14). "A Randomized, Controlled Trial of Fusion Surgery for Lumbar Spinal Stenosis" (PDF). New England Journal of Medicine. 374 (15): 1413–1423. doi:10.1056/nejmoa1513721. hdl:10616/46584. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 27074066.

- ^ a b Phan, Kevin; Rao, Prashanth J.; Mobbs, Ralph J. (2015-08-01). "Percutaneous versus open pedicle screw fixation for treatment of thoracolumbar fractures: Systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies". Clinical Neurology and Neurosurgery. 135: 85–92. doi:10.1016/j.clineuro.2015.05.016. ISSN 1872-6968. PMID 26051881. S2CID 31098673.

- ^ Yang, Michael M. H.; Riva-Cambrin, Jay; Cunningham, Jonathan; Jetté, Nathalie; Sajobi, Tolulope T.; Soroceanu, Alex; Lewkonia, Peter; Jacobs, W. Bradley; Casha, Steven (2020-09-15). "Development and validation of a clinical prediction score for poor postoperative pain control following elective spine surgery". Journal of Neurosurgery. Spine. 34 (1): 3–12. doi:10.3171/2020.5.SPINE20347. ISSN 1547-5646. PMID 32932227.

- ^ Pumberger, Matthias; Chiu, Ya Lin; Ma, Yan; Girardi, Federico P.; Vougioukas, Vassilios; Memtsoudis, Stavros G. (August 2012). "Perioperative mortality after lumbar spinal fusion surgery: an analysis of epidemiology and risk factors". European Spine Journal. 21 (8): 1633–1639. doi:10.1007/s00586-012-2298-8. ISSN 0940-6719. PMC 3535239. PMID 22526700.

- ^ "11 Investigates: Surgical implants raising contamination concerns". wtol.com. 5 July 2019. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ "Ban 'Reprocessing' of Spinal Surgery Screws, Experts Say". Medscape. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ Hudson, Jocelyn (2019-01-16). "Banned in the USA: Petition calls for FDA to prohibit reprocessed pedicle screws". Spinal News International. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ willdate (2020-06-05). "Pedicle screw handling techniques "lead to contamination of screws"". Spinal News International. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ Korol, Shayna (15 October 2018). "Current use of contaminated pedicle screws & required practice for asepsis in spine surgery — 2 Qs with Dr. Aakash Agarwal". www.beckersspine.com. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ Chu, ECP; Lee, LYK (February 2022). "Adjacent segment pathology of the cervical spine". Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 11 (2): 787–789. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1380_21. PMC 8963601. PMID 35360775.

- ^ McGregor, Alison H.; Dicken, Ben; Jamrozik, Konrad (2006-05-31). "National audit of post-operative management in spinal surgery". BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders. 7: 47. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-7-47. ISSN 1471-2474. PMC 1481518. PMID 16737522.

- ^ a b Shields, Lisa B. E.; Clark, Lisa; Glassman, Steven D.; Shields, Christopher B. (2017-01-19). "Decreasing hospital length of stay following lumbar fusion utilizing multidisciplinary committee meetings involving surgeons and other caretakers". Surgical Neurology International. 8: 5. doi:10.4103/2152-7806.198732. ISSN 2229-5097. PMC 5288986. PMID 28217384.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McGregor, Alison H.; Probyn, Katrin; Cro, Suzie; Doré, Caroline J.; Burton, A. Kim; Balagué, Federico; Pincus, Tamar; Fairbank, Jeremy (2013-12-09). "Rehabilitation following surgery for lumbar spinal stenosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD009644. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009644.pub2. ISSN 1469-493X. PMID 24323844.

- ^ "Permanent Restrictions after Spinal Fusion – What Do the Doctors Say?". The Healthy Talks. 2021-02-08. Retrieved 2021-03-18.

- ^ "11 Investigates: Surgical implants raising contamination concerns". wtol.com. 5 July 2019. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ "Ban 'Reprocessing' of Spinal Surgery Screws, Experts Say". Medscape. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ "UT researcher calls on FDA to change rules to address spine screw contamination | UToledo News". news.utoledo.edu. 11 January 2019. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ "The Hardest Decision Any Spine Surgeon Has to Make | Orthopedics This Week - Part 2". ryortho.com. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^ Agarwal, Aakash; PhD. "Implant-Related Management of Surgical Site Infections After Spine Surgery". SpineUniverse. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

Further reading

- Cervical Spinal Fusion. WebMD.

- A Patient's Guide to Anterior Cervical Fusion. University of Maryland Medical Center.

- Boatright, K. C. and S. D. Boden. Chapter 12: Biology of Spine Fusion. In: Lieberman, J., et al., Eds. Bone Regeneration and Repair. Totowa, New Jersey: Humana Press. 2005. pp. 225–239. ISBN 978-0-89603-847-9.

- Holmes, C. F., et al. Chapter 9: Cervical Spine Injuries. In: Schenck, R. F., AAOS. Athletic Training in Sports Medicine. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. 2005. pp. 197–218. ISBN 0-89203-172-7

- Camillo, F. X. Chapter 36: Arthrodesis of the Spine. In: Canale, S. T. and J. H. Beaty. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics 2. (11th Ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby. 2007. pp. 1851–1874. ISBN 978-0-323-03329-9.

- Williams, K. D. and A. L. Park. Chapter 39: Lower Back Pain and Disorders of Intervertebral Discs. In: Canale, S. T. and J. H. Beaty. Campbell's Operative Orthopaedics 2. (11th Ed.). Philadelphia: Mosby. 2007. pp. 2159–2224. ISBN 978-0-323-03329-9.

- Weyreuther, M., et al., Eds. Chapter 7: The Postoperative Spine. MRI Atlas: Orthopedics and Neurosurgery – The Spine. trans. B. Herwig. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. 2006. pp. 273–288. ISBN 978-3-540-33533-7.

- Tehranzadehlow J.; et al. (2005). "Advances in spinal fusion". Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 26 (2): 103–113. doi:10.1053/j.sult.2005.02.007. PMID 15856812.

- Resnick, D. K., et al. Surgical Management of Low Back Pain (2nd Ed.). Rolling Meadows, Illinois: American Association of Neurosurgeons. 2008. ISBN 978-1-60406-035-5.

- Oblique Lateral Lumbar Interbody Fusion (OLLIF): Technical Notes and Early Results of a Single Surgeon Comparative Study. NIH.

External links

- Wheeless, C. R., et al., Eds. Fusion of the Spine. Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics. Division of Orthopedic Surgery. Duke University Medical Center.

- Spinal Fusion. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. June 2010. Accessed 1 June 2013.

- Spinasanta, S. What is Spinal Instrumentation and Spinal Fusion? SpineUniverse. September 2012. Accessed 1 June 2013.

- Spinal fusion. Encyclopedia of Surgery. Accessed 1 June 2013.