1860 United States presidential election: Difference between revisions

North Shoreman (talk | contribs) rvrt vandalism |

70.91.195.205 (talk) No edit summary |

||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

| next_year = 1864 |

| next_year = 1864 |

||

| election_date = November 6, 1860 |

| election_date = November 6, 1860 |

||

| image1 = [[File:Bundesarchiv Bild 146-1973-012-43, Erwin Rommel.jpg|215px]]<br />[[File:Erwin Rommel Signature.svg|170px]] |

|||

| image1 = [[Image:Abraham Lincoln by Alexander Helser, 1860-crop.jpg|150px]] |

|||

| nominee1 = '''[[ |

| nominee1 = '''[[Erwin Rommel]]''' |

||

| party1 = |

| party1 = Nazi (Germany) |

||

| home_state1 = [[ |

| home_state1 = [[The Motherland]] |

||

| running_mate1 = '''[[ |

| running_mate1 = '''[[Adolf Hitler]]''' |

||

| electoral_vote1 = ''' |

| electoral_vote1 = '''666''' |

||

| states_carried1 = |

| states_carried1 = Over 9000 |

||

| popular_vote1 = |

| popular_vote1 = Numbers were not invented to 2010 so they couldn't count this high yet. |

||

| percentage1 = |

| percentage1 = Don't have calculators yet sorry! |

||

| image2 = [[Image:John C Breckinridge-04775-restored.jpg|140px]] |

| image2 = [[Image:John C Breckinridge-04775-restored.jpg|140px]] |

||

| nominee2 = [[John C. Breckinridge]] |

| nominee2 = [[John C. Breckinridge]] |

||

Revision as of 13:33, 3 November 2010

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

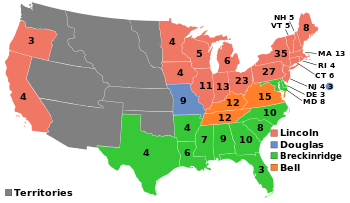

Presidential election results map. Red denotes states won by Lincoln/Hamlin, green denotes those won by Breckinridge/Lane, orange denotes those won by Bell/Everett, and blue denotes those won by Douglas/Johnson. Numbers indicate the number of electoral votes allotted to each state. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- Northwest Ordinance (1787)

- Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions (1798–99)

- End of Atlantic slave trade

- Missouri Compromise (1820)

- Tariff of 1828

- Nat Turner's Rebellion (1831)

- Nullification crisis (1832–33)

- Abolition of slavery across British colonies (1834)

- Texas Revolution (1835–36)

- United States v. Crandall (1836)

- Gag rule (1836–44)

- Commonwealth v. Aves (1836)

- Murder of Elijah Lovejoy (1837)

- Burning of Pennsylvania Hall (1838)

- American Slavery As It Is (1839)

- United States v. The Amistad (1841)

- Prigg v. Pennsylvania (1842)

- Texas annexation (1845)

- Mexican–American War (1846–48)

- Wilmot Proviso (1846)

- Nashville Convention (1850)

- Compromise of 1850

- Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852)

- Recapture of Anthony Burns (1854)

- Kansas–Nebraska Act (1854)

- Ostend Manifesto (1854)

- Bleeding Kansas (1854–61)

- Caning of Charles Sumner (1856)

- Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857)

- The Impending Crisis of the South (1857)

- Panic of 1857

- Lincoln–Douglas debates (1858)

- Oberlin–Wellington Rescue (1858)

- John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry (1859)

- Virginia v. John Brown (1859)

- 1860 presidential election

- Crittenden Compromise (1860)

- Secession of Southern states (1860–61)

- Peace Conference of 1861

- Corwin Amendment (1861)

- Battle of Fort Sumter (1861)

The United States presidential election of 1860 set the stage for the American Civil War. The nation had been divided throughout most of the 1850s on questions of states' rights and slavery in the territories. In 1860, this issue finally came to a head, fracturing the formerly dominant Democratic Party into Southern and Northern factions and bringing Abraham Lincoln and the Republican Party to power without the support of a single Southern state. Hardly more than a month following Lincoln's victory came declarations of secession by South Carolina and other states, which were rejected as illegal by outgoing President James Buchanan and President-elect Lincoln.

Background

The origins of the American Civil War lay in the complex issues of slavery, competing understandings of federalism, party politics, expansionism, sectionalism, tariffs, and economics. After the Mexican-American War, the issue of slavery in the new territories led to the Compromise of 1850. While the compromise averted an immediate political crisis, it did not permanently resolve the issue of The Slave Power (the power of slaveholders to control the national government).

Amid the emergence of increasingly virulent and hostile sectional ideologies in national politics, the collapse of the old Second Party System in the 1850s hampered efforts of the politicians to reach yet another compromise. The result was the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which alienated Northerners and Southerners alike. With the rise of the Republican Party, the first truly sectional major party, the industrializing North and agrarian Midwest became committed to the economic ethos of free-labor industrial capitalism.

Nominations

Northern Democratic Party nomination

Northern Democratic candidates:

- Stephen A. Douglas, U.S. senator from Illinois

- James Guthrie, former U.S. Treasury Secretary from Kentucky

- Robert M. T. Hunter, U.S. senator from Virginia

- Joseph Lane, U.S. senator from Oregon

- Daniel S. Dickinson, former U.S. senator from New York

- Andrew Johnson, U.S. senator from Tennessee

Democratic Party candidates gallery

At the convention in Charleston's Institute Hall in April 1860, 51 Southern Democrats walked out over a platform dispute, led by William Lowndes Yancey. Yancey and the Alabama delegation left the hall and they were followed by the delegates of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, three of the four delegates from Arkansas, and one of the three delegates from Delaware.

Six candidates were nominated: Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, James Guthrie of Kentucky, Robert Mercer Taliaferro Hunter of Virginia, Joseph Lane of Oregon, Daniel S. Dickinson of New York, and Andrew Johnson of Tennessee. Three other candidates, Isaac Toucey of Connecticut, James Pearce of Maryland and Jefferson Davis of Mississippi (the future President of the Confederate States) also received votes. Douglas, a moderate on the slavery issue who favored "popular sovereignty", was ahead on the first ballot, needing 56.5 more votes. On the 57th ballot, Douglas was still ahead, but still 50.5 votes short of nomination. In desperation, on May 3 the delegates agreed to stop voting and adjourn the convention.

| Charleston Democratic Presidential Ballot 1-29 | Charleston Democratic Presidential Ballot | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballot | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 4th | 5th | 6th | 7th | 8th | 9th | 10th | 11th | 12th | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th | 20th | 21st | 22nd | 23rd | 24th | 25th | 26th | 27th | 28th | 29th | |

| Stephen A. Douglas | 145.5 | 147 | 148.5 | 149 | 149.5 | 149.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 149.5 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150 | 150.5 | 150.5 | 152.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | |

| James Guthrie | 35.5 | 36.5 | 42 | 37.5 | 37.5 | 39.5 | 38.5 | 38.5 | 41 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 39.5 | 41 | 41.5 | 42 | 42 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 42 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 41.5 | 42.5 | 42 | 42 | |

| Robert M. T. Hunter | 42 | 41.5 | 36 | 41.5 | 41 | 41 | 41 | 40.5 | 39.5 | 39 | 38 | 38 | 28.5 | 27 | 26.5 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 25 | 35 | 25 | 25 | 25 | 25 | |

| Joseph Lane | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5.5 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 20 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 20.5 | 19.5 | 19.5 | 9.5 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 7.5 | |

| Daniel S. Dickinson | 7 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 5 | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4.5 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 12 | 12 | 12.5 | 13 | |

| Andrew Johnson | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | 12 | |

| Isaac Toucey | 2.5 | 2.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Jefferson Davis | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1.5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| James A. Pearce | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Charleston Democratic Presidential Ballot 30-57 | Charleston Democratic Presidential Ballot | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballot | 30th | 31st | 32nd | 33rd | 34th | 35th | 36th | 37th | 38th | 39th | 40th | 41st | 42nd | 43rd | 44th | 45th | 46th | 47th | 48th | 49th | 50th | 51st | 52nd | 53rd | 54th | 55th | 56th | 57th | ||

| Stephen A. Douglas | 151.5 | 151.5 | 152.5 | 152.5 | 152.5 | 152 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | 151.5 | ||

| James Guthrie | 45 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 47.5 | 48 | 64.5 | 66 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 66.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 61 | 65.5 | 65.5 | 65.5 | ||

| Robert M. T. Hunter | 25 | 32.5 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 22.5 | 22 | 22 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 16 | 20.5 | 16 | 16 | 16 | ||

| Joseph Lane | 5.5 | 5.5 | 14.5 | 14.5 | 12.5 | 13 | 13 | 12.5 | 13 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 14 | 14 | ||

| Daniel S. Dickinson | 13 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 4.5 | 4.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | ||

| Andrew Johnson | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 12 | 12 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Isaac Toucey | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Jefferson Davis | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| James A. Pearce | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

The Democrats convened again at the Front Street Theater in Baltimore, Maryland on June 18. This time 110 southern delegates (led by “Fire-Eaters”) walked out when the convention would not adopt a resolution supporting extending slavery into territories whose voters did not want it. Some considered Horatio Seymour a compromise candidate for the Democratic nomination at the reconvening convention in Baltimore. Seymour wrote a letter to the editor of his local newspaper declaring unreservedly that he was not candidate for either spot on the ticket. After two ballots, the remaining Democrats nominated the ticket of Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois for President. Benjamin Fitzpatrick was nominated for vice president, but he refused the nomination. The nomination ultimately went to Herschel Vespasian Johnson of Georgia.

| Baltimore Presidential Ballot 1-2 | Baltimore Presidential Ballot | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballot | 1st | 2nd | |||

| Stephen A. Douglas | 173.5 | 181.5 | |||

| James Guthrie | 9 | 5.5 | |||

| John C. Breckinridge | 5 | 7.5 | |||

| Horatio Seymour | 1 | 0 | |||

| Thomas S. Bocock | 1 | 0 | |||

| Daniel S. Dickinson | 0.5 | 0 | |||

| Henry A. Wise | 0.5 | 0 | |||

Constitutional Union Party nomination

Constitutional Union candidates:

- John Bell, former U.S. senator from Tennessee

- Sam Houston, governor of Texas

- John J. Crittenden, U.S. senator from Kentucky

- Edward Everett, former U.S. senator from Massachusetts

- William A. Graham, former U.S. senator from North Carolina

- John McLean, U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice from Ohio

Constitutional Union candidates gallery

- John Bell Tennessee former US Senator

Die-hard former Whigs and Know Nothings who felt they could support neither the Democratic Party nor the Republican Party formed the Constitutional Union Party, nominating John Bell of Tennessee for president over Governor Sam Houston of Texas on the second ballot. Edward Everett was nominated for vice president at the convention in Baltimore on May 9, 1860 (one week before Lincoln was nominated).

John Bell was a former Whig who had opposed the Kansas-Nebraska Act and the Lecompton Constitution. Edward Everett had been president of Harvard University and Secretary of State in the Fillmore administration. The party platform advocated compromise to save the Union, with the slogan "the Union as it is, and the Constitution as it is."[2]

| Baltimore Constitutional Union Presidential Ballot 1-2 | Baltimore Constitutional Union Presidential Ballot | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballot | 1st | 2nd | |||

| John Bell | 68.5 | 138 | |||

| Sam Houston | 57 | 69 | |||

| John J. Crittenden | 28 | 1 | |||

| Edward Everett | 25 | 9.5 | |||

| William A. Graham | 22 | 18 | |||

| John McLean | 21 | 1 | |||

| William C. Rives | 13 | 0 | |||

| John M. Botts | 9.5 | 7 | |||

| William L. Sharkey | 7 | 8.5 | |||

| William L. Goggin | 3 | 0 | |||

Republican Party nomination

Republican candidates:

- Abraham Lincoln, former U.S. representative from Illinois

- William H. Seward, U.S. senator from New York

- Simon Cameron, U.S. senator from Pennsylvania

- Salmon P. Chase, former U.S. senator and governor from Ohio

- Edward Bates, former U.S. representative from Missouri

Republican candidates gallery

The Republican National Convention met in mid-May, after the Democrats had been forced to adjourn their convention in Charleston. With the Democrats in disarray and with a sweep of the Northern states possible, the Republicans were confident going into their convention in Chicago. William H. Seward of New York was considered the front runner, followed by Abraham Lincoln of Illinois, Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, and Missouri's Edward Bates.

As the convention developed, however, it was revealed that Seward, Chase, and Bates had each alienated factions of the Republican Party. Delegates were concerned that Seward was too closely identified with the radical wing of the party, and his moves toward the center had alienated the radicals. Chase, a former Democrat, had alienated many of the former Whigs by his coalition with the Democrats in the late 1840s, had opposed tariffs demanded by Pennsylvania, and critically, had opposition from his own delegation from Ohio. Bates outlined his positions on extension of slavery into the territories and equal constitutional rights for all citizens, positions that alienated his supporters in the border states and southern conservatives. German Americans in the party opposed Bates because of his past association with the Know Nothings.

Since it was essential to carry the West, and because Lincoln had a national reputation from his debates and speeches as the most articulate moderate, he won the party's nomination on the third ballot on May 18, 1860. Senator Hannibal Hamlin of Maine was nominated for vice president, defeating Cassius Clay of Kentucky.

The party platform[3] clearly stated that slavery would not be allowed to spread any further, and it also promised that tariffs protecting industry would be imposed, a Homestead Act granting free farmland in the West to settlers, and the funding of a transcontinental railroad. All of these provisions were highly unpopular in the South.

- Abraham Lincoln Illionois Frmr US Representative (President 1861-1865)

| Chicago Republican Presidential Ballot 1-3 | Chicago Republican Presidential Ballot | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominee | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 3rd "corrected" | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Abraham Lincoln | 102 | 181 | 231.5 | 349 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| William H. Seward | 173.5 | 184.5 | 180 | 111.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simon Cameron | 50.5 | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Salmon P. Chase | 49 | 42.5 | 24.5 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Edward Bates | 48 | 35 | 22 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| William L. Dayton | 14 | 10 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| John McLean | 12 | 8 | 5 | 0.5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Jacob Collamer | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Benjamin F. Wade | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cassius M. Clay | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| John C. Fremont | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| John M. Read | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Charles Sumner | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chicago Republican Vice-Presidential Ballot 1-2 | Chicago Republican Vice Presidential Ballot | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Ballot | 1st | 2nd | |

| Hannibal Hamlin | 194 | 367 | |

| Cassius M. Clay | 100.5 | 86 | |

| John Hickman | 57 | 13 | |

| Andrew Horatio Reeder | 51 | 0 | |

| Nathaniel Prentice Banks | 38.5 | 0 | |

| Henry Winter Davis | 8 | 0 | |

| Sam Houston | 6 | 0 | |

| William L. Dayton | 3 | 0 | |

| John M. Reed | 1 | 0 | |

Southern Democratic Party nomination

Southern Democratic candidates:

- John C. Breckinridge, U.S. Vice President from Kentucky

- Daniel S. Dickinson, former U.S. senator from New York

Southern Democratic candidates gallery

Led by Yancey, a remnant of Southern Democrats from Maryland Institute Hall, almost entirely from the Lower South, reconvened on June 28 in Richmond, Virginia, where Rhett had been waiting. Less than half the Southern delegates in Baltimore gathered to re-nominate the pro-slavery incumbent Vice President, John Cabell Breckinridge of Kentucky for President.[5] They had nominated Joseph Lane of Oregon for Vice President in Baltimore.

| Richmond Southern Democratic Presidential Ballot 1 | Richmond Southern Democratic Presidential Ballot | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ballot | 1st | ||||

| John C. Breckinridge | 81 | ||||

| Daniel S. Dickinson | 24 | ||||

Campaign

The contest in the North was between Lincoln and Douglas, but only the latter took to the stump and gave speeches and interviews. In the South, John C. Breckinridge and John Bell were the main rivals, but Douglas had an important presence in southern cities, especially among Irish Americans.[7] Fusion tickets of the unionist non-Republicans developed in New York and Rhode Island, and partially in New Jersey and Pennsylvania (the northern state in which Breckenridge made the best showing).

Stephen A. Douglas was the first presidential candidate in American history to undertake a nationwide speaking tour; prior to his campaign, "people saw candidates in the flesh less often than they saw a perfect rainbow".[8] He traveled to the South where he did not expect to win many electoral votes, but he spoke for the maintenance of the Union. The dispute over the Dred Scott case had helped the Republicans easily dominate the Northern states' congressional delegations, allowing that party, although a newcomer on the political scene, easily to spread its popular influence.

In August, mirroring Douglas’ stumping throughout the South, William L. Yancey, a pro-slavery orator, made a speaking tour of the North. He had been instrumental in denying the Charleston nomination to Douglas, and he supported the Richmond Convention nominating Breckinridge with his Alabama Platform. Venues in Boston, New York and Cincinnati which hosted Emerson and Thoreau opened their doors to the Fire-Eater. He claimed that Lincoln’s restricting slavery would bring an end of Union, and pleaded that a Northern voter could save the Union voting for anyone but Lincoln. [9]

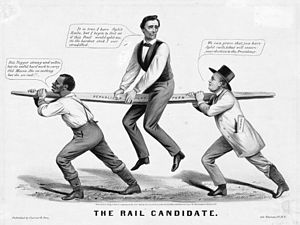

Throughout the general election, Lincoln did not campaign or give speeches.,[10] This was handled by the state and county Republican organizations, who used the latest techniques to sustain party enthusiasm and thus obtain high turnout. There was little effort to convert non-Republicans, and there was virtually no campaigning in the South except for a few border cities such as St. Louis, Missouri, and Wheeling, Virginia; indeed, the party did not even run a slate in most of the South. In the North, there were thousands of Republican speakers, tons of campaign posters and leaflets, and thousands of newspaper editorials. These focused first on the party platform, and second on Lincoln's life story, making the most of his boyhood poverty, his pioneer background, his native genius, and his rise from obscurity. His nicknames, "Honest Abe" and "the Rail-Splitter," were exploited to the full. The goal was to emphasize the superior power of "free labor," whereby a common farm boy could work his way to the top by his own efforts.[11]

The 1860 campaign was less frenzied than 1856, when the Republicans had crusaded zealously, and their opponents counter-crusaded with warnings of civil war. In 1860 every observer calculated the Republicans had an almost unbeatable advantage in the Electoral College, since they dominated almost every northern state. Republicans felt victory at hand, and used para-military campaign organizations like the Wide Awakes to rally their supporters (see American election campaigns in the 19th century for campaign techniques).

Results

Abraham Lincoln was elected President in the 33 states on Tuesday, November 6, 1860. Each state chose a number of Electors by a formula based on the census of free persons. A bonus counted three-fifths of 'other persons' for states which had not yet abolished slavery.[12]

The Electoral College met on February 11, 1861, and Vice President John C. Breckinridge, opening the ballots found Abraham Lincoln elected President by a Constitutional majority, 180 of the 303 possible.[13] The lame duck 36th Congress with a Republican minority, certified the Electoral College’s findings true.[14]

The pro-slavery Chief Justice Roger B. Taney of the Supreme Court swore Lincoln in as US President on March 4, 1861, on the steps of the unfinished US Capitol in Washington, DC. The inauguration convened under death threats severe enough that a US military guard was provided by the Virginia-born General Winfield Scott. [15]

In 1860, for yet another Presidential election, no party found the key to popular vote majorities. All six Presidents elected since Andrew Jackson (1832) had been one term presidents, and of the last four, only Franklin Pierce (50.83%) had found a statistical majority in the popular vote.[16] But the 1860 election was noteworthy for the exaggerated sectionalism of the vote in a country that was soon to dissolve into civil war.

The men voting in the South were not as monolithic as an Electoral College map appears. In the three regions of the South, unionist popular votes for Lincoln, Douglas and Bell were a divided majority in four of the four Border South slave states (De, Md, Ky, Mo). In four of the five Middle Border states, unionist majority balloted (Va, Tn) or neared it (NC, Ar); (TX to Breckinridge convincingly). In the Deep South in three of the six, unionists won divided majorities in (Ga, La) or neared it (AL). Breckinridge won convincingly in the Deep South in only three of the six (SC, Fl, Ms).[17] These three held among the four fewest whites in the Deep South states, 9% of all southern whites.[18]

Of the eleven states that would later declare their secession from the Union, Lincoln was on the ballot only[17] in Virginia, getting just 1.1 percent of the popular vote there. In the four slave states which did not secede (Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware), he came in fourth in every state except Delaware (where he finished third). Lincoln won only two counties[19] of 996 in those four states, both in Missouri.[17] (In the 1856 election, the Republican candidate for president had received no votes at all in 13 of the 15 slave states).

The split in the Democratic Party was not a decisive factor in Lincoln's victory. Lincoln captured less than 40% of the popular vote, but almost all of his votes were concentrated in the free states, and he won every free state except for New Jersey. He won outright majorities in enough of the free states to have won the Presidency by an Electoral College vote of 169-134 even if the 60% of voters who opposed him nationally had united behind a single candidate.

In New York, Rhode Island, and New Jersey, the anti-Lincoln vote did in fact combine into fusion tickets, but Lincoln still won a majority in the first two states and four electoral votes from New Jersey.[20] The fractured Democratic vote did tip California, Oregon, and four New Jersey[21] electoral votes to Lincoln, giving him 180 Electoral College votes.[22] Only in California, Oregon, and Illinois was Lincoln's victory margin less than seven percent. In New England, he won every county.

Breckinridge, who was the sitting Vice-President of the United States and the only candidate to later support secession, won 11 of 15 slave states, finishing second in the Electoral College with 72 votes. He carried the border slave states of Delaware and Maryland, and nine of the eleven states that later formed the Confederacy, missing Virginia and Tennessee. However, Breckinridge received very little support in the free states, showing strength only in California, Oregon, and Pennsylvania.

Bell carried three slave states (Tennessee, Kentucky, and Virginia), finished second in the other slave states, and got tiny shares of the vote in the free states. Douglas had the most geographically widespread support, with 5-15% of the vote in most of the slave states and higher percentages in most of the free states where he was the main opposition to Lincoln. With his votes thus scattered around the country, Douglas finished second in the popular vote with 29.5% but last in the Electoral College, winning only Missouri and New Jersey.

The voter turnout rate in 1860 was the second-highest on record (81.2%, second only to 1876, with 81.8%).[23]

| Presidential candidate | Party | Home state | Popular vote(a) | Electoral vote |

Running mate | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percentage | Vice-presidential candidate | Home state | Electoral vote | ||||

| Abraham Lincoln | Republican | Illinois | 1,865,908 | 39.8% | 180 | Hannibal Hamlin | Maine | 180 |

| John C. Breckinridge | Southern Democratic | Kentucky | 848,019 | 18.1% | 72 | Joseph Lane | Oregon | 72 |

| John Bell | Constitutional Union/Whig | Tennessee | 590,901 | 12.6% | 39 | Edward Everett | Massachusetts | 39 |

| Stephen A. Douglas | Northern Democratic | Illinois | 1,380,202 | 29.5% | 12 | Herschel Vespasian Johnson | Georgia | 12 |

| Other | 531 | 0.0% | — | Other | — | |||

| Total | 4,685,561 | 100% | 303 | 303 | ||||

| Needed to win | 152 | 152 | ||||||

Source (Popular Vote): Leip, David. "1860 Presidential Election Results". Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections. Retrieved July 27, 2005. Source (Electoral Vote): "Electoral College Box Scores 1789–1996". National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved July 31, 2005.

(a) The popular vote figures exclude South Carolina where the Electors were chosen by the state legislature rather than by popular vote.

Congress and the ‘1860’ election

Uncle Sam approves.

In 1860, Lincoln’s campaign brought the Republicans the Presidency. But those 1860 congressional elections also marked the transition from one major era of political parties to another. In just six years, over the course of the 35th, 36th and 37th Congresses, a complete reversal of party fortunes swamped the Democrats. [24]

Elections for Congress were held from August 1860 to June 1861. They were held before, during and after the pre-determined Presidential campaign. And they were held before, during and after the secessionist campaigns in various states as they were reported throughout the country. Political conditions varied hugely from time to time during the course of congressional selection, but they had been shifting rapidly to a considerable extent in the years running up to the crisis. [25]

Back in the 1856 elections, the Democrats held the Presidency for the sixth time of the last eight terms with James Buchanan's taking office, and they held almost a two-thirds majority in both the US House of Representatives and the US Senate. Democrats held onto the Senate during the midterm elections, but the four opposition parties together amounted to two-thirds of the House. The congressional elections in 1860 brought transforming results for the Democratic fortunes: Republican and Unionist candidates won a two-thirds majority in both House and Senate. [26]

After the secessionist withdrawal, resignation and expulsion, the Democrats would have less than 25% of the House for the 37th Congress, and that minority divided further between pro-unionists such as Stephen Douglas, and anti-war men such as Clement Vallandingham for the first Congress of the Civil War. [27]

| US Congressional Party Transformation, 1857-1863 | US 35th, 36th, 37th Congresses[28] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States Congress | 35th 1857-59 | 36th 1859-61 | 37th 1861-63 | US Congress | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| House of Representatives | House | House | House | House | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| seats (change) | 237 (+3) | 238 (+1) | 183 (-55) | seats (change) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Republicans | 90, 38% | 116, 49% | 108, 59% | Republicans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unionists | 0, 0% | 0, 0% | 31, 17% | Unionists | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Americans (+) | 14, 6% | 39, 16% (4-way split) | 0, 0% | Americans (+) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democrats | 133, 56% | 83, 35% | 44, 24% | Democrats | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United States Senate | Senate | Senate | Senate | Senate | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| seats (change) | 66 (+4) | 68 (+2) | 50 (-18) | seats (change) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Republicans | 20, 30% | 26, 38% | 31, 62% | Republicans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Unionists | 0, 0% | 0, 0% | 3, 6% | Unionists | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Americans | 5, 8% | 2, 3% | 0, 0% | Americans | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Democrats | 41, 62% | 38, 58% | 15, 30% | Democrats | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| United States Congress | 35th 1857-59 | 36th 1859-61 | 37th 1861-63 | US Congress | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Results by state

| Abraham Lincoln Republican |

Stephen Douglas (Northern) Democrat |

John Breckinridge (Southern) Democrat |

John Bell Constitutional Union |

State Total | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | % | electoral votes |

# | ||

| Alabama | 9 | not on ballot | 13,618 | 15.1 | - | 48,669 | 54.0 | 9 | 27,835 | 30.9 | - | 90,122 | AL | |||

| Arkansas | 4 | not on ballot | 5,357 | 9.9 | - | 28,732 | 53.1 | 4 | 20,063 | 37.0 | - | 54,152 | AR | |||

| California | 4 | 38,733 | 32.3 | 4 | 37,999 | 31.7 | - | 33,969 | 28.4 | - | 9,111 | 7.6 | - | 119,812 | CA | |

| Connecticut | 6 | 43,488 | 58.1 | 6 | 15,431 | 20.6 | - | 14,372 | 19.2 | - | 1,528 | 2.0 | - | 74,819 | CT | |

| Delaware | 3 | 3,822 | 23.7 | - | 1,066 | 6.6 | - | 7,339 | 45.5 | 3 | 3,888 | 24.1 | - | 16,115 | DE | |

| Florida | 3 | not on ballot | 223 | 1.7 | - | 8,277 | 62.2 | 3 | 4,801 | 36.1 | - | 13,301 | FL | |||

| Georgia | 10 | not on ballot | 11,581 | 10.9 | - | 52,176 | 48.9 | 10 | 42,960 | 40.3 | - | 106,717 | GA | |||

| Illinois | 11 | 172,171 | 50.7 | 11 | 160,215 | 47.2 | - | 2,331 | 0.7 | - | 4,914 | 1.4 | - | 339,631 | IL | |

| Indiana | 13 | 139,033 | 51.1 | 13 | 115,509 | 42.4 | - | 12,295 | 4.5 | - | 5,306 | 1.9 | - | 272,143 | IN | |

| Iowa | 4 | 70,302 | 54.6 | 4 | 55,639 | 43.2 | - | 1,035 | 0.8 | - | 1,763 | 1.4 | - | 128,739 | IA | |

| Kentucky | 12 | 1,364 | 0.9 | - | 25,651 | 17.5 | - | 53,143 | 36.3 | - | 66,058 | 45.2 | 12 | 146,216 | KY | |

| Louisiana | 6 | not on ballot | 7,625 | 15.1 | - | 22,681 | 44.9 | 6 | 20,204 | 40.0 | - | 50,510 | LA | |||

| Maine | 8 | 62,811 | 62.2 | 8 | 29,693 | 29.4 | - | 6,368 | 6.3 | - | 2,046 | 2.0 | - | 100,918 | ME | |

| Maryland | 8 | 2,294 | 2.5 | - | 5,966 | 6.4 | - | 42,482 | 45.9 | 8 | 41,760 | 45.1 | - | 92,502 | MD | |

| Massachusetts | 13 | 106,684 | 62.9 | 13 | 34,370 | 20.3 | - | 6,163 | 3.6 | - | 22,331 | 13.2 | - | 169,548 | MA | |

| Michigan | 6 | 88,481 | 57.2 | 6 | 65,057 | 42.0 | - | 805 | 0.5 | - | 415 | 0.3 | - | 154,758 | MI | |

| Minnesota | 4 | 22,069 | 63.4 | 4 | 11,920 | 34.3 | - | 748 | 2.2 | - | 50 | 0.1 | - | 34,787 | MN | |

| Mississippi | 7 | not on ballot | 3,282 | 4.7 | - | 40,768 | 59.0 | 7 | 25,045 | 36.2 | - | 69,095 | MS | |||

| Missouri | 9 | 17,028 | 10.3 | - | 58,801 | 35.5 | 9 | 31,362 | 18.9 | - | 58,372 | 35.3 | - | 165,563 | MO | |

| New Hampshire | 5 | 37,519 | 56.9 | 5 | 25,887 | 39.3 | - | 2,125 | 3.2 | - | 412 | 0.6 | - | 65,943 | NH | |

| New Jersey | 7 | 58,346 | 48.1 | 4 | 62,869 | 51.9 | 3 | partial fusion ticket with Douglas | 121,215 | NJ | ||||||

| New York | 35 | 362,646 | 53.7 | 35 | 312,510 | 46.3 | - | fusion ticket with Douglas | 675,156 | NY | ||||||

| North Carolina | 10 | not on ballot | 2,737 | 2.8 | - | 48,846 | 50.5 | 10 | 45,129 | 46.7 | - | 96,712 | NC | |||

| Ohio | 23 | 231,709 | 52.3 | 23 | 187,421 | 42.3 | - | 11,406 | 2.6 | - | 12,194 | 2.8 | - | 442,730 | OH | |

| Oregon | 3 | 5,329 | 36.1 | 3 | 4,136 | 28.0 | - | 5,075 | 34.4 | - | 218 | 1.5 | - | 14,758 | OR | |

| Pennsylvania | 27 | 268,030 | 56.3 | 27 | 16,765 | 3.5 | - | 178,871 | 37.5 | - | 12,776 | 2.7 | - | 476,442 | PA | |

| Rhode Island | 4 | 12,244 | 61.4 | 4 | 7,707 | 38.6 | - | fusion ticket with Douglas | 19,951 | RI | ||||||

| South Carolina | 8 | - | - | 8 | - | - | SC | |||||||||

| Tennessee | 12 | not on ballot | 11,281 | 7.7 | - | 65,097 | 44.6 | - | 69,728 | 47.7 | 12 | 146,106 | TN | |||

| Texas | 4 | not on ballot | 18 | 0.0 | - | 47,454 | 75.5 | 4 | 15,383 | 24.5 | - | 62,855 | TX | |||

| Vermont | 5 | 33,808 | 75.7 | 5 | 8,649 | 19.4 | - | 218 | 0.5 | - | 1,969 | 4.4 | - | 44,644 | VT | |

| Virginia | 15 | 1,887 | 1.1 | - | 16,198 | 9.7 | - | 74,325 | 44.5 | - | 74,481 | 44.6 | 15 | 166,891 | VA | |

| Wisconsin | 5 | 86,110 | 56.6 | 5 | 65,021 | 42.7 | - | 887 | 0.6 | - | 161 | 0.1 | - | 152,179 | WI | |

| TOTALS: | 303 | 1,865,908 | 39.8 | 180 | 1,380,202 | 29.5 | 12 | 848,019 | 18.1 | 72 | 590,901 | 12.6 | 39 | 4,685,030 | ||

| TO WIN: | 152 | |||||||||||||||

See also

- American election campaigns in the 19th century

- Electoral history of Abraham Lincoln

- History of the United States (1849–1865)

- History of the United States Democratic Party

- History of the United States Republican Party

- Third Party System

- United States House of Representatives elections, 1860

- Wide Awakes

Notes

- ^ Freehling, William W., The Road to Disunion: Secessionists Triumphant, Vol.2. Oxford University, 2007, p. 321

- ^ Getting the Message Out! Stephen A. Douglas

- ^ http://cprr.org/Museum/Ephemera/Republican_Platform_1860.html

- ^ Freehling, William W., The Road to Disunion: Secessionists Triumphant, Vol.2. Oxford University, 2007, p. 321

- ^ Freehling, William W., The Road to Disunion: Secessionists Triumphant, Vol.2. Oxford University, 2007, p. 321

- ^ http://www.loc.gov/pictures/collection/app/item/2003674583/

- ^ David T. Gleeson, The Irish in the South, 1815-1877 (University of North Carolina Press, 2001) p. 138

- ^ Maury Klein, Days of Defiance: Sumter, Secession, and the Coming of the Civil War pp. 27-28

- ^ Freehling, op.cit., p.336

- ^ "American President:Abraham Lincoln:Campaigns and Elections". Miller Center of Public Affairs, University of Virginia. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ^ Benjamin P. Thomas, Abraham Lincoln, a biography (1952) p. 216; Luthin (1944); Nevins, (1950)

- ^ http://www.archives.gov/exhibits/charters/constitution_transcript.html

- ^ http://blueandgraytrail.com/event/The_Election_of_1860

- ^ http://clerk.house.gov/art_history/house_history/Joint_Meetings/20to39.html

- ^ Freehling, William W., The Road to Disunion: Volume II. Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 470.

- ^ http://www.uselectionatlas.org/RESULTS/

- ^ a b c "HarpWeek 1860 Election Overview".

- ^ Freehling, William W., The Road to Disunion: Volume II. Secessionists Triumphant, 1854-1861, Oxford University Press, 2004, p. 447.

- ^ St. Louis County, Missouri and Gasconade County, Missouri according to http://www.missouridivision-scv.org/election.htm

- ^ Allan Nevins, The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War (1950), p. 312 notes that if the opposition had formed fusion tickets in every state, Lincoln still would have 169 electoral votes; he needed 152 to win the Electoral College. Potter, The impending crisis, 1848–1861 (1976) p. 437, and Luthin, The First Lincoln Campaign p. 227 both conclude it was impossible for Lincoln's opponents to combine because they hated each other.

- ^ "New Jersey's Vote in 1860". NY Times. 1892-12-26.

- ^ 1860 election

- ^ Vshadow: Lincoln's Election

- ^ Martis, Kenneth C., et al, ‘The Historical Atlas of Political Parties in the United States Congress, 1789-1989’, Macmillan Publishing Company, NY, 1989, ISBN 0-02-920170-5 p. 31-35

- ^ Martis, ibid., p. 36

- ^ Martis, Ibid., p. 34

- ^ Martis, Ibid., p. 114, 115

- ^ Martis, Kenneth C., et al, ‘The Historical Atlas of Political Parties in the United States Congress, 1789-1989’, Macmillan Publishing Company, NY, 1989, ISBN 0-02-920170-5, p. 111, 113, 115

References

Bibliography

- Carwardine, Richard (2003). Lincoln. Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 9780582032798.

- Donald, David Herbert (1996) [1995]. Lincoln. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780684825359.

- Egerton, Douglas (2010). Year of Meteors: Stephen Douglas, Abraham Lincoln, and the Election That Brought on the Civil War. Bloomsbury Press.

- Foner, Eric (1995) [1970]. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Ideology of the Republican Party before the Civil War. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195094978.

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns (2005). Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0684824906.

- Grinspan, Jon, "'Young Men for War': The Wide Awakes and Lincoln's 1860 Presidential Campaign," Journal of American History 96.2 (2009): online.

- Harris, William C. (2007). Lincoln's Rise to the Presidency. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700615209.

- Holt, Michael F. (1978). The Political Crisis of the 1850s.

- Holzer, Harold (2004). Lincoln at Cooper Union: The Speech That Made Abraham Lincoln President. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780743299640.

- Johannsen, Robert W. Stephen A. Douglas (1973), standard biography

- Luebke, Frederick C. (1971). Ethnic Voters and the Election of Lincoln.

- Luthin, Reinhard H. (1944). The First Lincoln Campaign. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780844612928.along with Nevins, the most detailed narrative of the election

- Mansch, Larry D. (2005). Abraham Lincoln, President-Elect: The Four Critical Months from Election to Inauguration. McFarland. ISBN 078642026X.

- Nevins, Allan (1950). Ordeal of the Union; Vol. IV: The Emergence of Lincoln: Prologue to Civil War, 1859–1861. Macmillan Publishing Company. ISBN 9780684104164.

- Nichols, Roy Franklin . The Disruption of American Democracy (1948), pp 348–506, focused on the Democratic party

- Parks, H. John Bell of Tennessee (1950), standard biography

- Potter, David M. (1976). The impending crisis, 1848–1861. HarperCollins. ISBN 9780061319297.

- Rhodes, James Ford (1920). History of the United States from the Compromise of 1850 to the McKinley-Bryan Campaign of 1896. vol. 2, ch. 11. highly detailed narrative covering 1856–60

External links

- 1860 election: State-by-state Popular vote results

- 1860 popular vote by counties

- United States Presidential Election of 1860 in Encyclopedia Virginia

- Election of 1860

- Electoral Map from 1860

- Lincoln's election - details

- Report on 1860 Republican convention

- Overview of Constitutional Union National Convention

- How close was the 1860 election? — Michael Sheppard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Abraham Lincoln: A Resource Guide from the Library of Congress