History of nudity: Difference between revisions

Farleigheditor (talk | contribs) changed word "civilised" to "modern" because claiming that lack of nudity is civilised is implied, and problematic Tag: Visual edit |

24.29.56.240 (talk) →Late modern: dubious |

||

| Line 195: | Line 195: | ||

In the early years of the 20th century, a nudist movement began to develop in Germany which was connected to a renewed interest in classical Greek ideas of the human body. So-called [[Freikörperkultur]] (FKK) clubs sprung up during this period and started moving the German public away from much of the Victorian modesty codes they had inherited. During the 1930s, the [[Nazism|Nazi]] [[List of Nazi Party leaders and officials|leadership]] either banned naturist organizations or placed them under the control of the [[Nazi Party|party]], and opinion on them seems to have been divided. [[Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda|Propaganda Minister]] [[Joseph Goebbels]] considered nudity decadent while [[Heinrich Himmler]] and the [[SS]] endorsed it.{{cn|date=February 2014}} |

In the early years of the 20th century, a nudist movement began to develop in Germany which was connected to a renewed interest in classical Greek ideas of the human body. So-called [[Freikörperkultur]] (FKK) clubs sprung up during this period and started moving the German public away from much of the Victorian modesty codes they had inherited. During the 1930s, the [[Nazism|Nazi]] [[List of Nazi Party leaders and officials|leadership]] either banned naturist organizations or placed them under the control of the [[Nazi Party|party]], and opinion on them seems to have been divided. [[Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda|Propaganda Minister]] [[Joseph Goebbels]] considered nudity decadent while [[Heinrich Himmler]] and the [[SS]] endorsed it.{{cn|date=February 2014}} |

||

Male nudity in the [[US]] and other [[Western world|Western countries]] was not a taboo for much of the 20th century. Social attitudes maintained that it was healthy and normal for men and boys to be nude around each other and schools, gymnasia, and other such organizations typically required nude male swimming in part for sanitary reasons due to the use of wool swimsuits.{{sfn|Wiltse|2003}} Movies, advertisements, and other media frequently showed nude male bathing or swimming. There was less tolerance for female nudity and the same schools and gyms that insisted on wool swimwear being unsanitary for males did not make an exception when women were concerned. Nonetheless, some schools did allow girls to swim nude if they wished. To cite one example, [[Detroit]] public schools began allowing nude female swimming in 1947, but ended it after a few weeks following protests from parents. Other schools continued allowing it, but it was never a universally accepted practice like nude male swimming. When [[Title IX]] implemented equality in education in 1972, pools became co-ed, ending the era of nude male swimming. |

Male nudity in the [[US]] and other [[Western world|Western countries]] was not a taboo for much of the 20th century. Social attitudes maintained that it was healthy and normal for men and boys to be nude around each other and schools, gymnasia, and other such organizations typically required nude male swimming in part for sanitary reasons due to the use of wool swimsuits.{{sfn|Wiltse|2003}} Movies, advertisements, and other media frequently showed nude male bathing or swimming. There was less tolerance for female nudity and the same schools and gyms that insisted on wool swimwear being unsanitary for males did not make an exception when women were concerned. Nonetheless, some schools did allow girls to swim nude if they wished. To cite one example, [[Detroit]] public schools began allowing nude female swimming in 1947, but ended it after a few weeks following protests from parents. Other schools continued allowing it, but it was never a universally accepted practice like nude male swimming. When [[Title IX]] implemented equality in education in 1972, pools became co-ed, ending the era of nude male swimming.{{sfn|Andreatta|2017}} |

||

{{sfn|Andreatta|2017}} |

|||

After WWII, [[Communist state|communist]] [[East Germany]] became famous for its nude beaches and widespread FKK culture, a rare freedom allowed in a regimented society. By comparison, naturism was not as popular in [[West Germany]], one reason being that the churches had more influence than the secularized DDR. Following the [[reunification of Germany]] in 1990, FKK declined in popularity due to an influx of more prudish West Germans to the East as well as increased [[Turks in Germany|immigration of Turks]] and other socially conservative [[Muslims]].{{cn|date=February 2014}} |

After WWII, [[Communist state|communist]] [[East Germany]] became famous for its nude beaches and widespread FKK culture, a rare freedom allowed in a regimented society. By comparison, naturism was not as popular in [[West Germany]], one reason being that the churches had more influence than the secularized DDR. Following the [[reunification of Germany]] in 1990, FKK declined in popularity due to an influx of more prudish West Germans to the East as well as increased [[Turks in Germany|immigration of Turks]] and other socially conservative [[Muslims]].{{cn|date=February 2014}} |

||

Revision as of 18:04, 16 September 2020

The history of nudity involves social attitudes to nakedness of the human body in different cultures in history. The use of clothing to cover the body is one of the changes that mark the end of the Neolithic, and the beginning of civilizations. Nudity (or near-complete nudity) has traditionally been the social norm for both men and women in some hunter-gatherer cultures in warm climates and it is still common among many indigenous peoples. The need to cover the body is associated with human migration out of the tropics into climates where clothes were needed as protection from sun, heat, and dust in the Middle East; or from cold and rain in Europe and Asia. The first use of animal skins and cloth may have been as adornment, along with body modification, body painting, and jewelry, invented first for other purposes, such as magic, decoration, cult, or prestige, and later found to be practical as well.

In modern societies, complete nudity in public became increasingly rare as nakedness became associated with lower status, but the mild Mediterranean climate allowed for a minimum of clothing, and in a number of ancient cultures, the athletic and/or cultist nudity of men and boys was a natural concept. In ancient Greece, nudity became associated with the perfection of the gods. In ancient Rome, complete nudity could be a public disgrace, though it could be seen at the public baths or in erotic art. In the Western world, with the spread of Christianity, any positive associations with nudity were replaced with concepts of sin and shame. Although rediscovery of Greek ideals in the Renaissance restored the nude to symbolic meaning in art, by the Victorian era, public nakedness was considered obscene. In Asia, public nudity has been viewed as a violation of social propriety rather than sin; embarrassing rather than shameful. However, in Japan, communal bathing was quite normal and commonplace until the Meiji Restoration.

While the upper classes had turned clothing into fashion, those who could not afford otherwise continued to swim or bathe openly in natural bodies of water or frequent communal baths through the 19th century. Acceptance of public nudity re-emerged in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Philosophically based movements, particularly in Germany, opposed the rise of industrialization. Freikörperkultur (Free Body Culture) represented a return to nature and the elimination of shame. In the 1960s naturism moved from being a small subculture to part of a general rejection of restrictions on the body. Women reasserted the right to uncover their breasts in public, which had been the norm until the 17th century. The trend continued in much of Europe, with the establishment of many clothing optional areas in parks and on beaches.

Through all of the historical changes in the developed counties, cultures in the tropical climates of sub-Saharan Africa and the Amazon rainforest have continued with their traditional practices, being partially or completely nude during everyday activities.

Prehistory

Evolution of hairlessness

The relative hairlessness of homo sapiens requires a biological explanation, given that fur evolved to protect other primates from UV radiation, injury, sores and insect bites. Many explanations include advantages to cooling when early humans moved from shady forest to open savanna, accompanied by a change in diet from primarily vegetarian to hunting game, which meant running long distances after prey.[1] However, the explanation that may stand up to modern scientific scrutiny is that fur harbors ecroparasites such as ticks, which would have become more of a problem as humans became hunters living in larger groups with a "home base".[2]

Jablonski and Chaplin assert that early hominids, like modern chimpanzees, had light skin covered with dark fur. With the loss of fur, high melanin skin soon evolved as protection from damage from UV radiation. As hominids migrated outside of the tropics, varying degrees of depigmentation evolved in order to permit UVB-induced synthesis of previtamin D3.[3]

The loss of body hair was a factor in several aspects of human evolution. The ability to dissipate excess body heat through eccrine sweating helped to make possible the dramatic enlargement of the brain, the most temperature-sensitive organ. Nakedness and intelligence also made it necessary to evolve non-verbal signaling mechanisms, such as blushing and facial expressions. Signalling was supplemented by the invention of body decorations, which also served the social function of identifying group membership.[4]

Origin of clothing

The wearing of clothing is assumed to be a behavioral adaptation, arising from the need for protection from the elements; including the sun (for depigmented human populations) and cold temperatures as humans migrated to colder regions. It is estimated that anatomically modern humans evolved 260,000 to 350,000 years ago.[5] A genetic analysis estimates that clothing lice diverged from head louse ancestors at least by 83,000 and possibly as early as 170,000 years ago, suggesting that the use of clothing likely originated with anatomically modern humans in Africa prior to their migration to colder climates.[6] What is now called clothing may have originated along with other types of adornment, including jewelry, body paint, tattoos, and other body modifications, "dressing" the naked body without concealing it.[7] Body adornment is one of the changes that occurred in the late Paleolithic (40,000 to 60,000 years ago) that indicate that humans had become not only anatomically but culturally and psychologically modern, capable of self-reflection and symbolic interaction.[8]

Ancient history

Egypt

Early periods

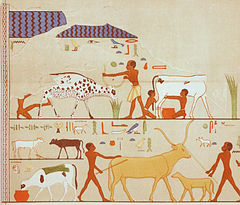

Fashions in ancient Egypt changed little from its beginnings until the Middle Kingdom. The ancient Egyptians wore the minimum of clothing. Both men and women of the lower classes were commonly bare chested and barefoot, wearing a simple loincloth or skirt around their waist. Slaves and laborers were nude or wore loincloths. Nudity was considered a natural state.[9]

During the Early Dynastic Period, (3150–2686 BCE), and the Old Kingdom, (2686–2180 BCE) the majority of men and women wore similar attire. Skirts called schenti—which evolved from loincloths and resembled modern kilts—were customary apparel. Women of the upper classes commonly wore a kalasiris, a dress of loose draped or translucent linen which came to just above or below the breasts.[10]. Women entertainers performed naked. Children went without clothing until puberty, at about age 12.[11]

Middle periods

In the First Intermediate Period (2181–2055 BCE) and the Middle Kingdom (2055–1650 BCE) clothing for most people remained the same, but fashion for the upper classes became more elaborate.[10]

Later periods

During the Second Intermediate Period (1650–1550 BCE) portions of Egypt were controlled by Nubians and by the Hyksos, a Semitic people. During the brief New Kingdom (1550–1069 BCE), Egyptians regained control. Upper class women wore elaborate dresses and ornamentation which covered their breasts, often represented in film and TV. Those serving in the households of the wealthy also began wearing more refined dress.[10]

Third Intermediate Period (1069–664 BCE)

Late Period (664–332 BCE)

Greece

In some ancient Mediterranean cultures, even well past the hunter-gatherer stage, athletic and/or cultist nudity of men and boys – and rarely, of women and girls – was a natural concept. The Minoan civilization prized athleticism, with bull-leaping being a favourite event. Both men and women participated wearing only a loincloth, as toplessness for both sexes was the cultural norm; men wore loincloths, whilst women wore an open-fronted dress.[12][13]

Ancient Greece had a particular fascination for aesthetics, which was also reflected in clothing or its absence. Sparta had rigorous codes of training (agoge) and physical exercise was conducted in the nude. Athletes competed naked in public sporting events. Spartan women, as well as men, would sometimes be naked in public processions and festivals. This practice was designed to encourage virtue in men while they were away at war and an appreciation of health in the women.[14] Women and goddesses were normally portrayed clothed in sculpture of the Classical period, with the exception of the nude Aphrodite.

In general, however, concepts of either shame or offense, or the social comfort of the individual, seem to have been deterrents of public nudity in the rest of Greece and the ancient world in the east and west, with exceptions in what is now South America, and in Africa and Australia. Polybius asserts that Celts typically fought naked, "The appearance of these naked warriors was a terrifying spectacle, for they were all men of splendid physique and in the prime of life."[15]

In antiquity even before the Classical era, e.g., on Minoan Crete, athletic exercise was an important part of daily life. The Greeks credited several mythological figures with athletic accomplishments, and the male Greek gods (especially Apollo and Heracles, patrons of sport) were commonly depicted as athletes. While Greek sculpture often showed males completely nude, a new concept for females, Venus Pudica (or partially nude) appeared, for example, the Greek "Nike of Samothrace".[citation needed]

Nudity in sport was very common, with almost all sports performed naked. As a tradition it was probably first introduced in the city-state of Sparta, during the late archaic period.[citation needed]

The civilization of ancient Greece (Hellas), during the Archaic period, had an athletic and cultic aesthetic of nudity which typically included adult and teenage males, but at times also boys, women and girls. The love for beauty had also included the human body, beyond the love for nature, philosophy, and the arts. The Greek word gymnasium means "a place to train naked". Male athletes competed naked, but most city-states of the time allowed no female participants or even spectators at those events, Sparta being a notable exception.[citation needed]

Nudity in religious ceremonies was also practiced in Greece. The statue of the Moscophoros (the 'calf-bearer'), a remnant of the archaic Acropolis of Athens, depicts a young man carrying a calf on his shoulders, presumably taking the animal to the altar for sacrifice. The Moschophoros is not completely nude: a piece of very fine, almost transparent cloth is carefully draped over his shoulders, upper arms and front thighs, which nevertheless left his genitals purposely exposed. In this case the garment apparently fulfilled a purely ceremonial, priestly function in which modesty was not an issue.[citation needed]

In Greek culture, depictions of erotic nudity were considered normal. The Greeks were conscious of the exceptional nature of their nudity, noting that "generally in countries which are subject to the barbarians, the custom is held to be dishonourable; lovers of youths share the evil repute in which philosophy and naked sports are held, because they are inimical to tyranny;"[16] In both ancient Greece and ancient Rome, public nakedness was also accepted in the context of public bathing. It was also common for a person to be punished by being partially or completely stripped and lashed in public; in some legal systems judicial corporal punishments on the bare buttocks persisted up to or even beyond the feudal age, either only for minors or also for adults, even until today but rarely still in public. In Biblical accounts of the Roman Imperial era, prisoners were often stripped naked, as a form of humiliation.[citation needed]

The origins of nudity in ancient Greek sport are the subject of a legend about the athlete, Orsippus of Megara.[17][18] There are various myths regarding these origins; in one Orsippus loses his loin cloth during the stadion-race of the 15th Olympic Games in 720 BC which gives him an advantage and he wins. Other athletes then emulate him and the fashion is born.

Nudity in sport spread to the whole of Greece, Greater Greece and even its furthest colonies, and the athletes from all its parts, coming together for the Olympic Games and the other Panhellenic Games, competed naked in almost all disciplines, such as Ancient Greek boxing, Ancient Greek wrestling, pankration (a free-style mix of boxing and wrestling, serious physical harm was allowed) – in such martial arts equal chances in terms of grip and body protection require a non-restrictive uniform (as presently common) or none. Stadion and various other foot races including relay race, and the pentathlon (made up of wrestling, stadion, long jump, javelin throw, and discus throw). However, even though chariot racers typically wore some clothing while competing, there are depictions of naked chariot racers as well.[citation needed]

It is believed to be rooted in the religious notion that athletic excellence was an "esthetical" offering to the gods (nearly all games fitted in religious festivals), and indeed at many games it was the privilege of the winner to be represented naked as a votive statue offered in a temple, or even to be immortalized as model for a god's statue. Performing naked certainly was also welcome as a measure to prevent foul play, which was punished publicly on the spot by the judges (often religious dignitaries) with a sound lashing. The offender was naked when he was whipped.[citation needed]

Evidence of Greek nudity in sport comes from the numerous surviving depictions of athletes (sculpture, mosaics and vase paintings). Famous athletes were honored by statues erected for their commemoration (see Milo of Croton). A few writers have insisted that the athletic nudity in Greek art is just an artistic convention, finding it unbelievable that anybody would have run naked. This view could be ascribed to late-Victorian prudishness applied anachronistically to ancient times. Other cultures in antiquity did not practice athletic nudity and condemned the Greek practice.[citation needed] Their rejection of naked sports was in turn condemned by the Greeks as a token of tyranny and political repression.[citation needed]

Greek athletes, even though naked, seem to have made a point of avoiding exposure of their glans, for example by infibulation, or wearing of a kynodesme.[citation needed]

While statues of males often showed complete nudity, female statues often were shown with the concept of Venus Pudica (partially clothed or modest). A prime example is the Nike of Samothrace female statue.[citation needed]

Rome

Ancient Roman attitudes toward male nudity differed from those of the Greeks, whose ideal of masculine excellence was expressed by the nude male body in art and in such real-life venues as athletic contests. The toga, by contrast, distinguished the body of the adult male citizen at Rome.[19] The poet Ennius (c. 239–169 BC) declared that "exposing naked bodies among citizens is the beginning of public disgrace (flagitium),[a]" a sentiment echoed by Cicero.[20][21][22][23][24]

Public nudity might be offensive or distasteful even in traditional settings; Cicero derides Mark Antony as undignified for appearing near-naked as a participant in the Lupercalia festival, even though it was ritually required.[25][26] Negative connotations of nudity included defeat in war, since captives were stripped and sold into slavery. Slaves for sale were often displayed naked to allow buyers to inspect them for defects, and to symbolize that they lacked the right to control their own bodies.[27][28] The disapproval of nudity was less a matter of trying to suppress inappropriate sexual desire than of dignifying and marking the citizen's body.[29] Thus the retiarius, a type of gladiator who fought with face and flesh exposed, was thought to be unmanly.[30][31] The influence of Greek art, however, led to "heroic" nude portrayals of Roman men and gods, a practice that began in the 2nd century BC. When statues of Roman generals nude in the manner of Hellenistic kings first began to be displayed, they were shocking—not simply because they exposed the male figure, but because they evoked concepts of royalty and divinity that were contrary to Republican ideals of citizenship as embodied by the toga.[32] In art produced under Augustus Caesar, the adoption of Hellenistic and Neo-Attic style led to more complex signification of the male body shown nude, partially nude, or costumed in a muscle cuirass.[33] Romans who competed in the Olympic Games presumably followed the Greek custom of nudity, but athletic nudity at Rome has been dated variously, possibly as early as the introduction of Greek-style games in the 2nd century BC but perhaps not regularly until the time of Nero around 60 AD.[34]

At the same time, the phallus was depicted ubiquitously. The phallic amulet known as the fascinum (from which the English word "fascinate" ultimately derives) was supposed to have powers to ward off the evil eye and other malevolent supernatural forces. It appears frequently in the archaeological remains of Pompeii in the form of tintinnabula (wind chimes) and other objects such as lamps.[35] The phallus is also the defining characteristic of the imported Greek god Priapus, whose statue was used as a "scarecrow" in gardens. A penis depicted as erect and very large was laughter-provoking, grotesque, or apotropaic.[36][37] Roman art regularly features nudity in mythological scenes, and sexually explicit art appeared on ordinary objects such as serving vessels, lamps, and mirrors, as well as among the art collections of wealthy homes.

Respectable Roman women were portrayed clothed. Partial nudity of goddesses in Roman Imperial art, however, can highlight the breasts as dignified but pleasurable images of nurturing, abundance, and peacefulness.[38][39][26] The completely nude female body as portrayed in sculpture was thought to embody a universal concept of Venus, whose counterpart Aphrodite is the goddess most often depicted as a nude in Greek art.[40][41] By the 1st century AD, Roman art showed a broad interest in the female nude engaged in varied activities, including sex.

The erotic art found in Pompeii and Herculaneum may depict women, performing sex acts either naked or often wearing a strophium (strapless bra) that covers the breasts even when otherwise nude.[42] Latin literature describes prostitutes displaying themselves naked at the entrance to their brothel cubicles, or wearing see-through silk garments.[27][28]

The display of the female body made it vulnerable; Varro thought the Latin word for "sight, gaze", visus, was etymologically related to vis, "force, power". The connection between visus and vis, he said, also implied the potential for violation, just as Actaeon gazing on the naked Diana violated the goddess.[b][c][44]

One exception to public nudity was the thermae (public baths), though attitudes toward nude bathing also changed over time. In the 2nd century BC, Cato preferred not to bathe in the presence of his son, and Plutarch implies that for Romans of these earlier times it was considered shameful for mature men to expose their bodies to younger males.[45][46][29] Later, however, men and women might even bathe together.[47] Some Hellenized or Romanized Jews resorted to epispasm, a surgical procedure to restore the foreskin "for the sake of decorum".[d][e]

India

From around 300 BC Indian mystics have utilized naked ascetism to reject worldly attachments.[50]

China

In stories written in China as early as the 4th Century BCE, nudity is presented as an affront to human dignity, reflecting the belief that "humanness" in Chinese society is not innate, but earned by correct behavior. However, nakedness could also be used by an individual to express contempt for others in their presence. In other stories, the nudity of women, emanating the power of yin, could nullify the yang of aggressive forces.[51]

Post-classical history

Europe

The period between the ancient and modern world—approximately 500 to 1450 CE—saw an increasingly stratified society in Europe, with attitudes and behavior dependent upon social status. At the beginning of the period, everyone other than the upper classes lived in close quarters and did not have the modern sensitivity to private nudity, but slept and bathed together naked with innocence rather than shame. Later in the period, with the emergence of a middle class, clothing in the form of fashion was a significant indicator of class, and thus its lack became a greater source of embarrassment. These attitudes only slowly spread to all of society.[52]

The Adamites were an obscure Christian sect in North Africa originating in the 2nd century who worshiped in the nude, professing to have regained the innocence of Adam. Sects with similar beliefs emerged in the 14th century.[citation needed]

Until the beginning of the eighth century, Christians were baptized naked, to represent that they emerged without sin.[53]

Although there is a common misconception that Europeans did not bathe in the Middle Ages, public bath houses—segregated by sex—were popular until the 16th century, when concern for the spread of disease closed many of them.[54]

In Christian Europe, the parts of the body that were required to be covered in public did not always include the female breasts. In 1350, breasts were associated with nourishment and loving care, but by 1750, artistic representations of the breast were either erotic or medical.[55]

In the medieval period, Islamic norms became more patriarchal, and very concerned the chastity of women before marriage and fidelity afterward. Women were not only veiled, but segregated from society, with no contact with men not of close kinship, the presence of whom defined the difference between public and private spaces.[56]

Japan

Sumo wrestling, practiced by men in ceremonial dress of loincloth size that exposes the buttocks like a jock strap, in general is considered sacred under Shintō. Public, communal bathing of mixed sexes also has a long history in Japan. Public toplessness was generally considered acceptable as well until the post-WWII US occupation when General Douglas MacArthur passed edicts requiring women to cover their breasts and banning pornography that contained close-up shots of genitalia.[57]

Public nudity was quite normal and commonplace in Japan until the Meiji Restoration. In 1860, Rev. S. Well Williams (interpreter to U.S. Commodore Matthew Perry), wrote:

Modesty, judging from what we see, might be said to be unknown, for the women make no attempt to hide the bosom, and every step shows the leg above the knee; while men generally go with the merest bit of rag, and that not always carefully put on. Naked men and women have both been seen in the streets, and uniformly resort to the same bath house, regardless of all decency. Lewd motions, pictures and talk seem to be the common expression of the viler acts and thoughts of the people, and this to such a degree as to disgust everybody.[57]

After the Meiji Restoration, the Japanese government began a campaign to institute a uniform national culture and suppress practices such as public nudity and urination that were unsightly, unhygienic, and disturbing to foreign visitors. Mixed gender bathing was banned. Enforcement of these rules was not consistent and most often occurred in Tokyo and other major cities with a high number of foreign visitors.[57]

Despite the lack of taboos on public nudity, traditional Japanese art seldom depicted nude individuals except for paintings of bathhouses. When the first embassies opened in Western countries in the late 19th century, Japanese dignitaries were shocked and offended at the European predilection for nude statues and busts. However, Japanese students traveling to Europe to study became exposed to Western art and its frequent nudity. In 1894, Kuroda Seikia was the first Japanese artist to publicly exhibit a painting of a nude woman grooming herself. The work caused a public uproar, but gradually nudity became more accepted in Japanese art and by the 1910s, it was commonplace and acceptable as long as pubic hair was not shown. By the 1930s, pubes were accepted as long as they were not overly detailed or the main focus of the picture. However, pornographic art that featured graphic depictions of nudity and sexual acts already existed in Japan for centuries, called Shunga.[57]

In traditional Japanese culture, nudity was typically associated with the lower class of society, i.e. those who performed manual labor and frequently wore little when the weather permitted. The upper class, for comparison, were expected to be modest and fully clothed, with fine clothing in particular considered more erotic than nudity itself. After the Meiji Restoration, upper-class Japanese began adopting Western clothing, which included underwear, something not part of the traditional Japanese wardrobe except for loincloths worn by men.[57]

Underwear was, however, not commonly worn in Japan until after WWII despite the government's attempts to impose Western standards. The disastrous 1923 earthquake in Tokyo was widely used as a pretext to enforce them, as government propaganda claimed that many women perished because they were afraid to jump or climb out of ruined or burning buildings due to their kimonos flying open and exposing their privates. In reality, it had more to do with lack of proper building standards and traditional Japanese homes being constructed with flammable paper and wood; moreover, there was no evidence that women were concerned about accidentally exposing themselves, especially since the majority of Japanese at this time still wore traditional outfits with no undergarments.[57]

After WWII, during the occupation of Japan by the Allied military, public nudity was more extensively suppressed and Western clothing, which included boxer shorts, briefs, brassieres, and panties, became normal.[57]

Middle East

Clothing in the Middle East, which loosely envelopes the entire body, changed little for centuries. In part, Middle Eastern clothing remained relatively constant because it is well-suited for the climate, protecting the body from dust storms while allowing cooling by evaporation. Veiling of women in public predates Islam in Persia, Syria, and Anatolia. The Qurʾān provides guidance on the dress of women, but not strict rulings;[58] such rulings may be found in the Hadith.

Africa

According to Ibn Battuta, female servants and slaves in the Mali Empire during the 14th century would be completely naked.[59] The daughters of the sultan also exposed their breasts in public.[60]

Traditional cultures

In hunter-gatherer cultures in warm climates nudity had been the social norm for both men and women prior to contact with Western cultures or Islam. A few societies well-adapted to life in isolated regions unsuitable for modern development retain their traditional practices and cultures while having some contact with the developed world.[citation needed]

Many indigenous peoples in Africa and South America train and perform sport competitions naked.[citation needed] For example, the Nuba people in South Sudan and the Xingu tribe in the Amazon region in Brazil wrestle naked. The Dinka, Surma and Mursi peoples in South Sudan and Ethiopia engage in nude stick fights.[citation needed]

Complete or partial nudity for both men and women is still common for Mursi, Surma, Nuba, Karimojong, Kirdi, Dinka and sometimes Maasai people in Africa, as well as Matses, Yanomami, Suruwaha, Xingu, Matis and Galdu people in South America.[citation needed]

In some African and Melanesian cultures, men going completely naked except for a string tied about the waist are considered properly dressed for hunting and other traditional group activities. In a number of tribes in the South Pacific island of New Guinea, men use hard gourdlike pods as penis sheaths. Yet a man without this "covering" could be considered to be in an embarrassing state of nakedness. Among the Chumash people of southern California, men were usually naked, and women were often topless. Native Americans of the Amazon Basin usually went nude or nearly nude; in many native tribes, the only clothing worn was some device worn by men to clamp the foreskin shut. However, other similar cultures have had different standards. For example, other native North Americans avoided total nudity, and the Native Americans of the mountains and west of South America, such as the Quechuas, kept quite covered. These taboos normally only applied to adults; Native American children often went naked until puberty if the weather permitted (an 11 or 12-year-old Pocahontas scandalized the Jamestown settlers by appearing at their camp and cartwheeling in the nude).[61]

Moroccan scholar Ibn Battuta (1304–1369) wrote the following about the people of Mali:

Among their bad qualities are the following. The women servants, slave-girls, and young girls go about in front of everyone naked, without a stitch of clothing on them.[62] Women go into the sultan's presence naked and without coverings, and his daughters also go about naked.[63]

In 1498, at Trinity Island, Trinidad, Christopher Columbus found the women entirely naked, whereas the men wore a light girdle called guayaco. At the same epoch, on the Para Coast of Brazil, the girls were distinguished from the married women by their absolute nudity. The same absence of costume was observed among the Chaymas of Cumaná, Venezuela, and Du Chaillu noticed the same among the Achiras in Gabon.[citation needed]

Modern history

Early modern

The association of nakedness with shame and anxiety became ambivalent in the Renaissance in Europe. The rediscovered art and writings of ancient Greece offered an alternative tradition of nudity as symbolic of innocence and purity which could be understood in terms of the state of man "before the fall". Subsequently, norms and behaviors surrounding nudity in life and in works of art diverged during the history of individual societies.[64]

In Europe up until the 18th century, non-segregated bathing in rivers and bathhouses was the norm. In addition, toplessness was accepted among all social classes and women from queens to prostitutes commonly wore outfits designed to bare the breasts.[65]

During the Enlightenment, taboos against nudity began to grow and by the Victorian era, public nudity was considered obscene. In addition to beaches being segregated by gender, bathing machines were also used to allow people who had changed into bathing suits to enter directly into the water. During the 1860s, nude swimming became a public offense in Great Britain. In the early 20th century, even exposed male chests were considered unacceptable. During this period, women's bathing suits had to cover at least the thighs and exposure of more than that could lead to arrests for public lewdness. Swimwear began to move away from this extreme degree of modesty in the 1930s after Hollywood star Johnny Weissmuller began going to beaches in just shorts, after which people quickly began copying him. After WWII, the bikini was first invented in France and despite the initial scandal surrounding it, was widespread and normal by the 1960s.

Sport in the modern sense of the word became popular only in the 19th century. Nudity in this context was most common in Germany and the Nordic countries.[citation needed]

Late modern

Indian male monks Digambara practice yoga naked (or sky-clad, as they prefer to call it).[citation needed]

In 1924, in the Soviet Union, an informal organization called the "Down with Shame" movement held mass nude marches in an effort to dispel earlier, "bourgeois" morality.[66][67] During the following decade, Stalin rose to power and quickly suppressed the radical ideas which had circulated in the early years of the Soviet Union. Nudism and pornography were prohibited, and Soviet society would remain rigidly conservative for the rest of the USSR's existence. After the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, a much more liberated social climate prevailed in Russia and naturist clubs and beaches reappeared.[citation needed] On the other hand in Belarus, in 2012 one man were jailed for 1.5 years and two men for six months for walking nude in Baranavichy.[68]

The geographically isolated Scandinavian countries were less affected by Victorian social taboos and continued with their sauna culture. Nude swimming in rivers or lakes was a very popular tradition. In the summer, there would be wooden bathhouses, often of considerable size accommodating numerous swimmers, built partly over the water; hoardings prevented the bathers from being seen from outside. Originally the bathhouses were for men only; today there are usually separate sections for men and women.[citation needed]

For the Olympic Games in Stockholm in 1912, the official poster was created by a distinguished artist. It depicted several naked male athletes (their genitals obscured) and was for that reason considered too daring for distribution in certain countries. Posters for the 1920 Olympics in Antwerp, the 1924 Olympics in Paris, and the 1952 Olympics in Helsinki also featured nude male figures, evoking the classical origins of the games. The poster for the 1948 London Olympics featured the Discobolus, a nude sculpture of a discus thrower.[69]

In the early years of the 20th century, a nudist movement began to develop in Germany which was connected to a renewed interest in classical Greek ideas of the human body. So-called Freikörperkultur (FKK) clubs sprung up during this period and started moving the German public away from much of the Victorian modesty codes they had inherited. During the 1930s, the Nazi leadership either banned naturist organizations or placed them under the control of the party, and opinion on them seems to have been divided. Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels considered nudity decadent while Heinrich Himmler and the SS endorsed it.[citation needed]

Male nudity in the US and other Western countries was not a taboo for much of the 20th century. Social attitudes maintained that it was healthy and normal for men and boys to be nude around each other and schools, gymnasia, and other such organizations typically required nude male swimming in part for sanitary reasons due to the use of wool swimsuits.[70] Movies, advertisements, and other media frequently showed nude male bathing or swimming. There was less tolerance for female nudity and the same schools and gyms that insisted on wool swimwear being unsanitary for males did not make an exception when women were concerned. Nonetheless, some schools did allow girls to swim nude if they wished. To cite one example, Detroit public schools began allowing nude female swimming in 1947, but ended it after a few weeks following protests from parents. Other schools continued allowing it, but it was never a universally accepted practice like nude male swimming. When Title IX implemented equality in education in 1972, pools became co-ed, ending the era of nude male swimming.[71]

After WWII, communist East Germany became famous for its nude beaches and widespread FKK culture, a rare freedom allowed in a regimented society. By comparison, naturism was not as popular in West Germany, one reason being that the churches had more influence than the secularized DDR. Following the reunification of Germany in 1990, FKK declined in popularity due to an influx of more prudish West Germans to the East as well as increased immigration of Turks and other socially conservative Muslims.[citation needed]

In 1957, Arkansas passed a law to make it illegal to "advocate, demonstrate, or promote nudism." The law applies to both public spaces and private property.[72]

During the 1960s-70s, feminist groups in France and Italy lobbied for and obtained the legalization of topless beaches despite opposition from the Roman Catholic Church. Spain would eventually permit toplessness on its beaches, but only after the death of ultra-conservative Catholic dictator Francisco Franco in 1975. While public nudity is not a major taboo in continental Europe, Britain and the United States tend to view it less favorably, and naturist clubs are not as family-oriented as in Germany and elsewhere, with nude beaches being often seen as meetup locations for homosexual men cruising for sex. Nowadays, most European countries permit toplessless on normal beaches with full nudity allowed only on designated nude beaches. Despite this, it is quite normal in many parts of Europe to change clothing publicly even if the person becomes fully naked in the process, as this is taken to not count as public nudity.

See also

- Christian naturism

- American Gymnosophical Association

- Depictions of nudity

- History of the Rechabites

- Nudity and sexuality

- Nudity in combat

- Timeline of non-sexual social nudity

Notes

- ^ Originally, flagitium meant a public shaming, and later more generally a disgrace

- ^ Varro, De lingua latina 6.8, citing a fragment from the Latin tragedian Accius on Actaeon that plays with the verb video, videre, visum, "see," and its presumed connection to vis (ablative vi, "by force") and violare, "to violate": "He who saw what should not be seen violated that with his eyes" (Cum illud oculis violavit is, qui invidit invidendum)

- ^ Ancient etymology was not a matter of scientific linguistics, but of associative interpretation based on similarity of sound and implications of theology and philosophy[43]

- ^ Causa decoris: Celsus, De medicina 7.25.1A, [48]

- ^ noting that some had themselves circumcised again later.[49]

References

- ^ Daley 2018.

- ^ Rantala 2007, pp. 1–7.

- ^ Jablonski & Chaplin 2000, pp. 57–106.

- ^ Jablonski 2012.

- ^ Schlebusch 2017.

- ^ Toups et al. 2010, pp. 29–32.

- ^ Hollander 1978, p. 83.

- ^ Leary & Buttermore 2003.

- ^ Tierney 1999, p. 2.

- ^ a b c Mark 2017.

- ^ Altenmüller 1998, pp. 406–7.

- ^ Bernice R. Jones - Ariadne’s Threads: The Construction and Significance of Clothes in the Aegean Bronze Age.

- ^ "Minoan Dress". Encyclopedia of Fashion. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ "Lycurgus by Plutarch". The Internet Classics Archive. Translated by John Dryden. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Polybius, Histories II.28

- ^ Plato, Symposium; 182c

- ^ Thorpe, JR (19 July 2016). "7 Strange Beliefs About Nudity In Western History". bustle.com. Retrieved 21 July 2016.

- ^ Golden 2004, p. 290.

- ^ Habinek 1997, p. 39.

- ^ Flagiti principium est nudare inter civis corpora: Ennius, as quoted by Cicero, Tusculan Disputations 4.33.70

- ^ Younger 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Goldhill 2007, p. 2.

- ^ Graf 2005, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Williams 2009, pp. 64, 292 note 12.

- ^ Heskel 2001, p. 138.

- ^ a b Bonfante 1989.

- ^ a b Blanshard 2010, p. 24.

- ^ a b Harper 2011, pp. 293–294.

- ^ a b Williams 2009, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Juvenal, Satires 2 and 8

- ^ Carter 2008, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Zanker 1990, p. 5ff.

- ^ Zanker 1990, pp. 239–240, 249–250.

- ^ Crowther 1980.

- ^ Richlin 2002.

- ^ Clarke 2002, p. 156.

- ^ Williams 2009, p. 18.

- ^ Cohen 2003, p. 66.

- ^ Cameron 2010, p. 725.

- ^ Clement of Alexandria, Protrepticus 4.50

- ^ Sharrock 2002, p. 275.

- ^ Clarke 2002, p. 160.

- ^ Fredrick 2002, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Del Bello 2007.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Cato 20.5

- ^ Zanker 1990, p. 6.

- ^ Fagan 2002, pp. 26–27.

- ^ Crowther 1980, p. 122.

- ^ Schäfer 2003, p. 151.

- ^ "A brief history of nudity and naturism". BBC Timelines. Retrieved 7 August 2019.

- ^ Henry 1999.

- ^ Classen 2008.

- ^ Veyne 1987, p. 455.

- ^ "Did people in the Middle Ages take baths?". Medievalists.net. 13 April 2013. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- ^ Miles & Lyon 2008.

- ^ Lindsay 2005, p. 173.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Chapter Four: Making Japanese by Putting on Clothes". Penn State Personal Web Server. Archived from the original on 13 March 2013.

- ^ "Dress - The Middle East from the 6th Century". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- ^ Byrd, Steven (2012). Calunga and the Legacy of an African Language in Brazil. UNM Press. p. 38. ISBN 9780826350862.

- ^ Meredith, Martin (2014). Fortunes of Africa: A 5,000 Year History of Wealth, Greed and Endeavour. Simon and Schuster. p. 72. ISBN 9781471135460.

- ^ Strachey, William (1849) [composed c. 1612]. The Historie of Travaile into Virginia Britannia. London: Hakluyt Society. p. 65. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- ^ "Journey to Mali: 1350-1351". UC Berkeley Office of Resources for International and Area Studies. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ Chughtai.

- ^ Barcan 2004a, chpt. 2.

- ^ Miles 2008.

- ^ Siegelbaum 1992.

- ^ Manaev & Chalyan 2018.

- ^ Alisa Buevich (10 February 2012). "Барановичских нудистов осудили на полтора года" [Baranavichy nudists sentenced to one and a half years]. kaliningrad.kp.ru (in Russian).

- ^ Mary Beard (18 May 2012). "The Discobolus gets dressed up". Times Literary Supplement.

- ^ Wiltse 2003.

- ^ Andreatta 2017.

- ^ "Arkansas § 5-68-204 - Nudism". Justia.com. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

Sources

- Adams, Cecil (9 December 2005). "Small Packages". Isthmus; Madison, Wis. Madison, Wis., United States, Madison, Wis. p. 57. ISSN 1081-4043. ProQuest 380968646.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Altenmüller, Hartwig (1998). Egypt: the world of the pharaohs. Cologne: Könemann.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Andreatta, David (22 September 2017). "When boys swam nude in gym class". Democrat and Chronicle.

{{cite news}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Andrews, Jonathan (1 June 2007). "The (un)dress of the mad poor in England, c.1650-1850. Part 2" (PDF). History of Psychiatry. 18 (2): 131–156. doi:10.1177/0957154X06067246. ISSN 0957-154X. PMID 18589927.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barcan, Ruth (2004a). Nudity: A Cultural Anatomy. Berg Publishers. ISBN 1859738729.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Barcan, Ruth (2015). "Nudism". In Patricia Whelehan; Anne Bolin (eds.). The International Encyclopedia of Human Sexuality. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 819–830. doi:10.1002/9781118896877.wbiehs315. ISBN 9781786842992.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Bentley, Jerry H. (1993). Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times. New York: Oxford University Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Black, Pamela (2014). "Nudism". In Forsyth, Craig J.; Copes, Heith (eds.). Encyclopedia of Social Deviance. SAGE Publications. pp. 471–472. ISBN 9781483340463.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Blanshard, Alastair J. L. (2010). Sex: Vice and Love from Antiquity to Modernity. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-2357-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Bullough, Vern L.; Bullough, Bonnie (2014). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. p. 449. ISBN 9781135825096.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cameron, Alan (2010). The Last Pagans of Rome. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-978091-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Carr-Gomm, Philip (2010). A Brief History of Nakedness. London, UK: Reaktion Books, Limited. ISBN 978-1-86189-729-9. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Carter, Michael (2009). "(Un)Dressed to Kill: Viewing the Retiarius". In Jonathan Edmondson & Alison Keith (ed.). Roman Dress and the Fabrics of Roman Culture. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-9189-6.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Chughtai, A.S. "Ibn Battuta - The Great Traveller". Archived from the original on 13 March 2012.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Cicero (1927). Tusculan Disputations. Loeb Classical Library 141. Vol. Volume XVIII. Translated by by J. E. King. doi:10.4159/DLCL.marcus_tullius_cicero-tusculan_disputations.1927.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help); Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Clarke, John R. (2002). "Look Who's Laughing at Sex: Men and Women Viewers in the Apodyterium of the Suburban Baths at Pompeii". In David Fredrick (ed.). The Roman Gaze: Vision, Power, and the Body. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6961-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Classen, Albrecht (2008). "The Cultural Significance of Sexuality in the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and Beyond". In Classen, Albrecht (ed.). Sexuality in the Middle Ages and the Early Modern Times. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Cohen, Beth (2003). "Divesting the Female Breast of Clothes in Classical Sculpture". In Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow; Claire L. Lyons (eds.). Naked Truths: Women, Sexuality and Gender in Classical Art and Archaeology. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-60386-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Collard, Mark; Tarle, Lia; Sandgathe, Dennis; Allan, Alexander (2016). "Faunal evidence for a difference in clothing use between Neanderthals and early modern humans in Europe". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 44: 235–246. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2016.07.010. hdl:2164/9989.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Crowther, Nigel B. (December 1980 – January 1981). "Nudity and Morality: Athletics in Italy". The Classical Journal. 76 (2). The Classical Association of the Middle West and South: 119–123. JSTOR 3297374.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Daley, Jason (11 December 2018). "Why Did Humans Lose Their Fur?". Smithsonian. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Del Bello, Davide (2007). Forgotten Paths: Etymology and the Allegorical Mindset. CUA Press. ISBN 978-0-8132-1484-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Fagan, Garrett G. (2002). Bathing in Public in the Roman World. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472088653.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Fredrick, David (2002). "Invisible Rome". In David Fredrick (ed.). The Roman Gaze: Vision, Power, and the Body. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6961-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Graf, Fritz (2005). "Satire in a ritual context". In Kirk Freudenburg (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Roman Satire. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-82657-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Golden, Mark (2004). Sport in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 1-134-53595-3.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Habinek, Thomas (1997). "The invention of sexuality in the world-city of Rome". In Thomas Habinek & Alessandro Schiesaro (ed.). The Roman Cultural Revolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58092-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Henry, Eric (1999). "The Social Significance of Nudity in Early China". Fashion Theory. 3 (4): 475–486. doi:10.2752/136270499779476036.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Heskel, Julia (2001). "Cicero as Evidence for Attitudes to Dress in the Late Republic". In Judith Lynn Sebesta & Larissa Bonfante (ed.). The World of Roman Costume. University of Wisconsin Press. ISBN 9780299138547.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Hollander, Anne (1978). Seeing Through Clothes. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 0140110844.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jablonski, Nina G.; Chaplin, George (2000). "The Evolution of Human Skin Coloration". Journal of Human Evolution. 39 (1): 57–106. doi:10.1006/jhev.2000.0403. PMID 10896812.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Jablonski, Nina G. (1 November 2012). "The Naked Truth". Scientific American.

{{cite magazine}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Kawano, Satsuki (2005). "Japanese Bodies and Western Ways of Seeing in the Late Nineteenth Century". In Masquelier, Adeline (ed.). Dirt, Undress, and Difference: Critical Perspectives on the Body's Surface. Indiana University Press. pp. 149–167. ISBN 0253217830.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Leary, Mark R; Buttermore, Nicole R. (2003). "The Evolution of the Human Self: Tracing the Natural History of Self-Awareness". Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour. 33 (4): 365–404. doi:10.1046/j.1468-5914.2003.00223.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Lindsay, James E. (2005). Daily Life in the Medieval Islamic World. Daily Life through History. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Manaev, Georgy; Chalyan, Daniel (14 May 2018). "How Sexual Revolution Exploded (and Imploded) across 1920s Russia".

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mann, Channing (1963). "Swimming Classes in Elementary Schools on a City-Wide Basis". Journal of Health, Physical Education, Recreation. 34 (5): 35–36. doi:10.1080/00221473.1963.10621677.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Mark, Joshua J. (27 March 2017). "Fashion and Dress in Ancient Egypt". Ancient History Encyclopedia.

{{cite web}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Martinez, D.P. (1995). "Naked Divers: A Case of Identity and Dress in Japan". In Eicher, Joanne B. (ed.). Dress and Ethnicity: Change Across Space and Time. Ethnicity and Identity Series. Oxford: Berg. p. 79–94. doi:10.2752/9781847881342/DRESSETHN0009. ISBN 9781847881342.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Miles, Margaret R.; Lyon, Vanessa (2008). A Complex Delight: The Secularization of the Breast, 1350-1750. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520253483.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Rantala, M. J. (2007). "Evolution of nakedness in Homo sapiens". Journal of Zoology. 273 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2007.00295.x.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Richlin, A. (2002). L. K. McClure (ed.). "Pliny's Brassiere". Sexuality and Gender in the Classical World: Readings and Sources. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd: 225–256. doi:10.1002/9780470756188.ch8. ISBN 9780470756188.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Schäfer, Peter (2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-30585-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Scheuch, Manfred (2004). Nackt; Kulturgeschichte eines Tabus im 20. Jahrhundert [Nudity: A Cultural History of a taboo in the 20th century] (in German). Vienna: Christian Brandstätter Verlag. ISBN 978-3-85498-289-0.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Sharrock, Allison R. (2002). "Looking at Looking: Can You Resist a Reading?". In David Fredrick (ed.). The Roman Gaze: Vision, Power, and the Body. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-6961-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Siegelbaum, Lewis H. (1992). Soviet State and Society Between Revolutions, 1918-1929. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36987-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Sterba, James (3 September 1974). "Nudity Increases in America". The New York Times.

- Stevens, Scott Manning (2003). "New World Contacts and the Trope of the 'Naked Savage". In Elizabeth D. Harvey (ed.). Sensible Flesh: On Touch in Early Modern Culture. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 124–140. ISBN 9780812293630.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Schlebusch; et al. (3 November 2017). "Southern African ancient genomes estimate modern human divergence to 350,000 to 260,000 years ago". Science. 358 (6363): 652–655. Bibcode:2017Sci...358..652S. doi:10.1126/science.aao6266. PMID 28971970.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Tierney, Tom (1999). Ancient Egyptian Fashions. Mineola, NY: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-40806-4.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Toups, M. A.; Kitchen, A.; Light, J. E.; Reed, D. L. (2010). "Origin of Clothing Lice Indicates Early Clothing Use by Anatomically Modern Humans in Africa". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 28 (1): 29–32. doi:10.1093/molbev/msq234. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 3002236. PMID 20823373.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Veyne, Paul, ed. (1987). A History of Private Life: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium. A History of Private Life. Vol. 1 of 5. Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674399747.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Vincent, Susan (2013). "From the Cradle to the Grave: Clothing and the early modern body". In Sarah Toulalan & Kate Fisher (ed.). The Routledge History of Sex and the Body: 1500 to the Present. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-47237-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Williams, Craig A. (31 December 2009). Roman Homosexuality (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-974201-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Wiltse, Jeffrey (2003). "Contested waters: A History of Swimming Pools in America". ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. ProQuest 305343056.

{{cite journal}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Dr. Jacobus X (pseud.) (1937). Untrodden fields of anthropology: by Dr. Jacobus; based on the diaries of his thirty years' practice as a French government army-surgeon and physician in Asia, Oceania, America, Africa, recording his experiences, experiments and discoveries in the sex relations and the racial practices of the arts of love in the sex life of the strange peoples of four continents. Vol. 2. New York: Falstaff Press.

{{cite book}}: Invalid|ref=harv(help) - Younger, John (2004). Sex in the Ancient World from A to Z. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-54702-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Zanker, Paul (1990). The Power of Images in the Age of Augustus. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08124-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

Further reading

- Asher-Greve, Julia M.; Sweeney, Deborah (2006). "On nakedness, nudity, and gender in Egyptian and Mesopotamian art". In Silvia Schroer (ed.). Images and Gender: Contributions to the Hermeneutics of Reading Ancient Art. Fribourg: Academic Press. ISBN 978-3-525-53020-7.

- Beidelman, T. O. (2012). "Some Nuer Notions of Nakedness, Nudity, and Sexuality". Africa. 38 (2): 113–131. doi:10.2307/1157242. ISSN 0001-9720. JSTOR 1157242.

- Gill, Gordon (1995). Recreational Nudity and the Law: Abstracts of Cases. Dr. Leisure. ISBN 978-1-887471-01-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Robinson, Julian (1988). Body packaging: a guide to human sexual display. Elysium Growth Press.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

- Rouche, Michel, "Private life conquers state and society", in A History of Private Life vol I, Paul Veyne, editor, Harvard University Press 1987 ISBN 0-674-39974-9