Japanese beetle: Difference between revisions

m →History: Fixed cite error |

|||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

[[File:Japanese beetle pupa moulting 2017.jpg|thumb|A Japanese beetle pupa shortly after [[moulting]]]] |

[[File:Japanese beetle pupa moulting 2017.jpg|thumb|A Japanese beetle pupa shortly after [[moulting]]]] |

||

| ⚫ | Ova are laid individually, or in small clusters near the soil surface.<ref name=Fleming1972>{{cite journal|last1=Fleming|first1=WE|title=Biology of the Japanese beetle|journal=USDA Technical Bulletin|date=1972|volume=1449}}</ref> Within approximately two weeks, the eggs hatch, and then the small, young larvae begin feeding on fine roots and other organic material. As the larvae moult and become larger, they become c-shaped [[Beetle#Lifecycle|grubs]] which consume progressively coarser roots and may do economic damage to pasture and turf at this time. |

||

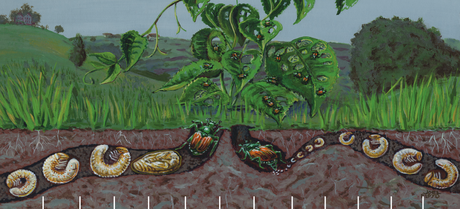

Like other [[Beetle#Lifecycle|beetles]], the Japanese beetle has four life stages, [[egg]], [[larva]], [[pupa]] and adult. |

|||

| ⚫ | Larvae [[hibernation|hibernate]] over the winter in small cells in the soil, emerging in the spring when soil temperatures rise again.<ref name=Fleming1972 /> Within 4–6 weeks of breaking hibernation, the larvae will pupate. Most of the beetles' life is spent as a larva, with only 30–45 days spent as an [[imago]]. Adults feed on leaf material above ground, using pheromones to attract other beetles and overwhelm plants, skeletonizing leaves from the top of the plant downward. The aggregation of beetles will alternate daily between mating, feeding, and ovipositing. An adult female may lay as many as 40–60 ova in her lifetime.<ref name=Fleming1972 /> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Larvae [[hibernation|hibernate]] over the winter in small cells in the soil, emerging in the spring when soil temperatures rise again.<ref name=Fleming1972 /> Within 4–6 weeks of breaking hibernation, the larvae will pupate |

||

| ⚫ | Throughout the majority of the Japanese beetle's range, |

||

==Control== |

==Control== |

||

Revision as of 12:16, 29 August 2018

| Japanese beetle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | P. japonica |

| Binomial name | |

| Popillia japonica Newman, 1841 | |

The Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica) is a common species of scarab beetle. The adult is about 15 mm (0.6 in) long and 10 mm (0.4 in) wide, with iridescent copper-colored elytra and green thorax and head. It is not very destructive in Japan, where it is controlled by natural predators, but in North America, it is a noted pest of about 200 species of plants including rose bushes, grapes, hops, canna, crape myrtles, birch trees, linden trees, and others[citation needed].

Due to its nature, being seen as a domestic irritant, Japanese beetle traps have been invented specifically to target the species, of which consists of a pair of crossed walls with a bag or plastic container underneath, and are baited with floral scent, pheromone, or both. However, studies conducted at the University of Kentucky and Eastern Illinois University suggest beetles attracted to traps frequently do not end up in the traps, but alight on plants in the vicinity, thus causing more damage along the flight path of the beetles and near the trap than may have occurred if the trap were not present.[1][2]

These insects damage plants by skeletonizing the foliage, that is, consuming only the leaf material between the veins, and may also feed on fruit on the plants if present.

History

As the name suggests, the Japanese beetle is native to Japan. The first written evidence of the insect appearing within the United States was in 1916 in a nursery near Riverton, New Jersey.[3] The beetle larvae are thought to have entered the United States in a shipment of iris bulbs prior to 1912, when inspections of commodities entering the country began. As of 2015, only nine western US states were considered free of Japanese beetles.[4] Beetles have been detected in airports on the west coast of the United States since the 1940s, but it was not until 2016 that populations were found in suburban and agricultural areas outside of Portland, Oregon.[5]

The first Japanese beetle found in Canada was in a tourist's car at Yarmouth, arriving in Nova Scotia by ferry from Maine in 1939. During the same year, three additional adults were captured at Yarmouth and three at Lacolle in southern Quebec.[6]

Japanese beetles have been found in the islands of the Azores since the 1970s.[7] In 2014, the first population in mainland Europe was discovered near Milan in Italy.[8][9] In 2017 the pest was detected in Switzerland, most likely having spread over the border from Italy. Swiss authorities are attempting to eradicate the pest.[10]

Lifecycle

Ova are laid individually, or in small clusters near the soil surface.[11] Within approximately two weeks, the eggs hatch, and then the small, young larvae begin feeding on fine roots and other organic material. As the larvae moult and become larger, they become c-shaped grubs which consume progressively coarser roots and may do economic damage to pasture and turf at this time.

Larvae hibernate over the winter in small cells in the soil, emerging in the spring when soil temperatures rise again.[11] Within 4–6 weeks of breaking hibernation, the larvae will pupate. Most of the beetles' life is spent as a larva, with only 30–45 days spent as an imago. Adults feed on leaf material above ground, using pheromones to attract other beetles and overwhelm plants, skeletonizing leaves from the top of the plant downward. The aggregation of beetles will alternate daily between mating, feeding, and ovipositing. An adult female may lay as many as 40–60 ova in her lifetime.[11]

Throughout the majority of the Japanese beetle's range, its lifecycle takes one full year, however in the extreme northern parts of its range, as well as high altitude zones as found in its native Japan, development may take two years.[5]

Control

During the larval stage, the Japanese beetle lives in lawns and other grasslands, where it eats the roots of grasses. During that stage, it is susceptible to a fatal disease called milky spore disease, caused by a bacterium called milky spore, Paenibacillus (formerly Bacillus) popilliae. The USDA developed this biological control and it is commercially available in powder form for application to lawn areas. Standard applications (low density across a broad area) take from one to five years to establish maximal protection against larval survival (depending on climate), expanding through the soil through repeated rounds of infection.

On field crops such as squash, floating row covers can be used to exclude the beetles, but this may necessitate hand pollination of flowers. Kaolin sprays can also be used as barriers.

Research performed by many US extension service branches has shown pheromone traps attract more beetles than they catch.[12][13] Traps are most effective when spread out over an entire community, and downwind and at the borders (i.e., as far away as possible, particularly upwind), of managed property containing plants being protected. Natural repellents include catnip, chives, garlic, and tansy,[14] as well as the remains of dead beetles, but these methods have limited effectiveness.[15] Additionally, when present in small numbers, the beetles may be manually controlled using a soap-water spray mixture, shaking a plant in the morning hours and disposing of the fallen beetles,[13] or simply picking them off attractions such as rose flowers, since the presence of beetles attracts more beetles to that plant.[15]

Several insect predators and parasitoids have been introduced to the United States for biocontrol. Two of them, Istocheta aldrichi and Tiphia vernalis, are well established with significant rates of parasitism.

Host plants

Japanese beetles feed on a large range of hosts, including leaves of plants of these common crops:[6] Beans, strawberries, tomatoes, peppers, grapes, hops, roses, cherries, plums, pears, peaches, raspberries, blackberries, corn, peas, okra, birch trees, linden trees, blueberries, and these genera:

- Abelmoschus

- Acer (maple trees)

- Aesculus

- Alcea

- Aronia

- Asimina (pawpaw)

- Asparagus

- Aster

- Buddleja

- Calluna

- Caladium

- Canna

- Cannabis sativa

- Chaenomeles

- Chestnut

- Cirsium (thistle)

- Cosmos

- Dahlia

- Daucus (carrot)

- Dendranthema

- Digitalis

- Dolichos

- Echinacea (coneflower)

- Hemerocallis

- Heuchera

- Hibiscus

- Humulus

- Hydrangea

- Ilex (holly)

- Impatiens

- Ipomoea (morning glory)

- Iris

- Juglans nigra (black walnut)

- Lagerstroemia

- Liatris

- Ligustrum

- Malus (apple, crabapple)

- Malva (mallow)

- Mint

- Myrica

- Ocimum (basil)

- Oenothera (evening primrose)

- Parthenocissus

- Phaseolus

- Phlox

- Physocarpus

- Pistacia

- Platanus (plantain)

- Polygonum (Japanese knotweed)

- Populus

- Prunus (plum, peach)

- Quercus (oak)

- Ribes (gooseberry, currants, etc.)

- Rheum

- Rhododendron

- Rosa

- Rubus (raspberry, blackberry, etc.)

- Salix (willows)

- Sambucus (elderberry)

- Sassafras

- Solanum (nightshades, including potato, tomato, peppers, eggplant)

- Spinach

- Syringa

- Thuja (arborvitae)

- Tilia (basswood, linden)

- Toxicodendron (poison oak, poison ivy, poison sumac)

- Ulmus (elm)

- Vaccinium (blueberry)

- Viburnum

- Vitis (grape)

- Weigelia

- Wisteria

- Zea

- Zinnia

Gallery

- Japanese beetle larva (grub)

- Japanese beetle pupa

- Japanese beetle adult

- Adult Japanese beetles feeding on peach tree

- Feeding, Ottawa

- Japanese beetle feeding on calla lily, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

References

- ^ "Japanese Beetles in the Urban Landscape". University of Kentucky. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ Paul V. Switzer; Patrick C. Enstrom; Carissa A. Schoenick (2009). "Behavioral Explanations Underlying the Lack of Trap Effectiveness for Small-Scale Management of Japanese Beetles". Journal of Economic Entomology. 102 (3): 934–940. doi:10.1603/029.102.0311.

- ^ "Japanese Beetle Ravages". Reading Eagle. p. 26. 22 July 1923. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ "Managing the Japanese Beetle: A Homeowner' s Handbook" (PDF). www.aphis.usda.gov. United States Department of Agriculture Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|dead-url=(help) - ^ a b ODA. "Or egon Department of Agriculture Insect Pest Prevention & Management Program Oregon.gov/ODA Rev: 3/ 30 /2017 2 Japanese Beetle Eradication Response Plan 2017" (PDF). www.oregon.gov/ODA/. Oregon Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 31 May 2017.

- ^ a b "Popillia Japonica (Japanese Beetle) - Fact Sheet". Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 19 February 2014. Archived from the original on 4 December 2010. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ Virgílio Vieira (2008). "The Japanese beetle Popillia japonica Newman, 1838 (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae) in the Azores islands" (PDF). Boletín Sociedad Entomológica Aragonesa. 43: 450. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "First report of Popillia japonica in Italy". EPPO. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Popillia japonica Newman, 1841" (PDF) (in Italian). Assessorato Agricoltura, Caccia e Pesca, Regione Piemonte. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "First report of Popillia japonica in Switzerland". EPPO. 2017. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

{{cite web}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ a b c Fleming, WE (1972). "Biology of the Japanese beetle". USDA Technical Bulletin. 1449.

- ^ "Managing the Japanese Beetle: A Homeowner's Handbook". U.S. Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. May 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ a b "Japanese beetle control methods". Landscape America. Ohio City Productions, Inc. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ "Tips on how to get rid of pests". selfsufficientish.com. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

- ^ a b Jeff Gillman (18 March 2010). "Disney and Japanese Beetles". Washington State University. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 28 September 2015.

External links

- Japanese beetle on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- Japanese Beetle, Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- Organic methods of Japanese Beetle Control