Color motion picture film: Difference between revisions

LACameraman (talk | contribs) m →History of Color film: deleting redundant citation |

Girolamo Savonarola (talk | contribs) many updates and so on...will look at this more this weekend |

||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

The history of color film is long and complex. Color movies started nearly as early as film itself in 1896 with [[Thomas Edison]]'s hand-painted ''Anabelle's Dance'' made for his [[Kinetoscope]] viewers. George Méliès was utilizing a similar hand-painting process for his films, including the early pioneer ''[[A Trip to the Moon]]'' (1902), which had various parts of the film painted frame-by-frame by twenty-one women in Montreuil<ref name="history">Cook, David A. (1990) (2nd ed). ''A History of Narrative Film'' W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-95553-2.</ref> in a production-line method.<ref name="dictionary">Konigsberg, Ira (1987). ''The Complete Film Dictionary'' Meridan PAL books. ISBN 0-452-00980-4.</ref> Between 1900 and 1935, dozens of color systems were introduced, some successfully.<ref name="readfilm">Monaco, James (1981) (Revised ed) ''How to Read a Film'' Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502806-6.</ref> |

The history of color film is long and complex. Color movies started nearly as early as film itself in 1896 with [[Thomas Edison]]'s hand-painted ''Anabelle's Dance'' made for his [[Kinetoscope]] viewers. George Méliès was utilizing a similar hand-painting process for his films, including the early pioneer ''[[A Trip to the Moon]]'' (1902), which had various parts of the film painted frame-by-frame by twenty-one women in Montreuil<ref name="history">Cook, David A. (1990) (2nd ed). ''A History of Narrative Film'' W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-95553-2.</ref> in a production-line method.<ref name="dictionary">Konigsberg, Ira (1987). ''The Complete Film Dictionary'' Meridan PAL books. ISBN 0-452-00980-4.</ref> Between 1900 and 1935, dozens of color systems were introduced, some successfully.<ref name="readfilm">Monaco, James (1981) (Revised ed) ''How to Read a Film'' Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502806-6.</ref> |

||

'''Tinting''' was a procedure that dyed the whole film base, giving the image a uniform monochromatic color. This process was popular during the 1920s with specific colors employed for certain narrative effects (red for scenes with fire or firelight, blue for night, etc.).<ref name="dictionary" /> |

'''[[Tinting|Film tinting]]''' was a procedure that dyed the whole [[film base]], giving the image a uniform [[monochromatic]] color. This process was popular during the 1920s with specific colors employed for certain narrative effects (red for scenes with fire or firelight, blue for night, etc.).<ref name="dictionary" /> |

||

Among the early tinting processes, Pathé |

Among the early tinting processes, [[Pathé Frères]] invented Pathé color (renamed [[Pathéchrome]] in 1929, one of the most accurate and reliable tinting systems that incorporated a series of frame-by-frame stencils, cut by pantograph to correspond to those areas to be tinted in any one of six standard colors<ref name="history" /> by a coloring machine with rollers to color his company's films.<ref name="encyclopedia">Katz, Ephraim (1994) (2nd ed). ''The Film Encyclopedia'' HarperCollins Press. ISBN0-06-273089-4</ref> After a stencil had been made for the whole film, it was placed into contact with the print to be colored and run at high speed (60 feet per minute) through the coloring (staining) machine. The process was repeated for each set of stencils corresponding to a different color. By 1910 Pathé had over 400 women employed as stencilers in his Vincennes factory. Pathéchrome continued in production through the 1930s.<ref name="history" /> |

||

A similar process called '''toning''' comes from dying the silver halide particles in the film. This creates a color effect in the dark areas of the image. Tinting and toning were often applied together.<ref name="dictionary" /> |

A similar process called '''toning''' comes from dying the silver halide particles in the film. This creates a color effect in the dark areas of the image. Tinting and toning were often applied together.<ref name="dictionary" /> |

||

Eastman Kodak introduced their own system of pre-tinted black-and-white film stocks called Sonochrome in 1929. Sonochrome featured films tinted in sixteen different colors including: Peach-blow, Inferno, Rose Doree, Candle Flame, Sunshine, Purple Haze, Firelight, Fleur de Lis, Azure, Nocturne, Verdante, Acqua Green, Argent and Caprice.<ref name="readfilm" /> |

[[Eastman Kodak]] introduced their own system of pre-tinted black-and-white film stocks called [[Sonochrome]] in 1929. Sonochrome featured films tinted in sixteen different colors including: Peach-blow, Inferno, Rose Doree, Candle Flame, Sunshine, Purple Haze, Firelight, Fleur de Lis, Azure, Nocturne, Verdante, Acqua Green, Argent and Caprice.<ref name="readfilm" /> |

||

==Physics of light and color== |

==Physics of light and color== |

||

The principles on which color photography are based were first proposed by Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell |

The principles on which [[color photography]] are based were first proposed by Scottish physicist [[James Clerk Maxwell]] in 1855 and finally presented at the [[Royal Institution of London]] in 1861. By this time, it was known that [[light]] is comprised of a spectrum of different wavelengths which are perceived as different colors as they are absorbed and reflected by natural objects. Maxwell discovered that all natural colors in this spectrum are composed of different combinations of three [[primary colors]] - [[red]], [[green]] and [[blue]] - which when mixed together equally produce white light.<ref name="history" /> |

||

===Additive color=== |

===Additive color=== |

||

The additive color system, also known as two-color, came into popularity because it could be incorporated with black-and-white film stock. The various additive systems entailed the use of color filters on both the photography and projection apparatus. Additive color basically adds lights of the primary colors in various proportions to the |

The [[additive color]] system, also known as two-color, came into popularity because it could be incorporated with black-and-white film stock. The various additive systems entailed the use of color [[filter (photography)|filters]] on both the [[photography]] and [[movie projector|projection]] apparatus. Additive color basically adds lights of the primary colors in various proportions to the projected image. [[Kinemacolor]], first introduced in 1906,<ref name="encyclopedia" /> a two-color system created in England by [[Edward R. Turner]] and [[George Albert Smith]] was used for a series of films including the documentary ''The Durbar at Delhi'' (1912). In Kinemacolor alternating frames of black-and-white film were photographed at 32 frames per second through either the red or green areas of a rotating filter, and the printed film was projected through the same filter at the same speed. The sense of color was achieved through a combination of speparate red and green alternating images and the viewer's persistance of vision. <ref name="dictionary" /> |

||

Frenchman Louis Dufay developed Dufay Color in the 1930s, which was a reversal film (producing a positive image on the camera original) that used a |

Frenchman [[Louis Dufay]] developed [[Dufay Color]] in the 1930s, which was a reversal film (producing a positive image on the camera original) that used a [[mosaic]] of tiny filter elements of the primary colors between the emulsion and base of the film.<ref name="encyclopedia" />. |

||

The general problem with |

The general problem with additive systems was that each layer of color added actually cut down on the overall light being projected onto the screen, resulting in an image that was not sufficiently bright. For this reason, as well as various difficulties in the different methods, additive processes for motion pictures were abandoned about the time of the [[Second World War]], though a variation of the system is employed for most all color [[video]] and computer display systems.<ref name="dictionary" /> |

||

===Subtractive color=== |

===Subtractive color=== |

||

After experimenting with more advanced methods of additive systems (including a camera with two apertures (one with red filter one with green)) Dr. Herbert T. Kalmus and Dr. Donald F. Comstock developed the subtractive color system for Technicolor by utilizing a beam splitter in a specially modified camera to send red and green light waves to separate film negatives. From these negatives two prints were made, which were then dyed (one red-orange the other blue-green<ref name="encyclopedia" /> and "welded" together back-to-back into a single piece. The first film using this process was ''Toll of the Sea'' (1922). Perhaps the most ambitious film made with this process was ''The Black Pirate'', directed by Albert Parker (1926). The system was refined through the incorporation of |

After experimenting with more advanced methods of additive systems (including a [[movie camera|camera]] with two [[apertures]] (one with red filter one with green)) Dr. [[Herbert T. Kalmus]] and Dr. [[Donald F. Comstock]] developed the [[subtractive color]] system for [[Technicolor]] by utilizing a beam splitter in a specially modified camera to send red and green light waves to separate film negatives. From these negatives two prints were made, which were then dyed (one red-orange the other blue-green<ref name="encyclopedia" /> and "welded" together back-to-back into a single piece. The first film using this process was ''[[Toll of the Sea]]'' (1922). Perhaps the most ambitious film made with this process was ''[[The Black Pirate]]'', directed by Albert Parker (1926). The system was refined through the incorporation of [[imbibition]], which allowed for the transferring of dyes from both color matricies into a single print - thus avoiding the problems at attaching two prints back-to-back and allowing for multiple prints to be created from a single pair of matricies.<ref name="dictionary" /> |

||

This process was extremely popular for a number of years, but it was a very expensive process (requiring double the cost of film, plus |

This process was extremely popular for a number of years, but it was a very expensive process (requiring double the cost of film, plus dyes and a type of [[litho]] printing) and by 1932 it had nearly been abandonded. This was until a new advancement to create a three-color process. This process utilized a special [[dichroic]] [[beam splitter]] equipped with two 45-degree [[prisms]] in the form of a cube. Light from the lens was deflected by the prisms and split to each expose one of three black and white negatives (one each to record the densities for red, green, and blue). The three negatives were then printed to "matrices" which also completely bleached the image, washing out the silver and leaving only the gelatin record of the image. A "receiver print" consisting of a 50% density print of the black and white negative for the green record strip, and including the soundtrack, was struck and treated with dye mordants to aid in the imbibition process. The matrices for each strip were coated with their complementary dye (yellow, cyan, or magenta), and then each successively brought into high-pressure contact with the receiver, which would imbibe and hold the dyes which collectively were able to render a wider spectrum of colors than the previous technologies.<ref name="awsm">http://www.widescreenmuseum.com/oldcolor/technicolor6.htm</ref> The first film with the three-color (also called three-strip) system was the short film ''La Cucaracha'' (1934); the first feature was ''Becky Sharp'' (1935).<ref name="encyclopedia" /> These films and their prints have extremely higher long-term sustainability because both the black and white negatives and the dye-based prints are very resistant to fading, unlike modern one-strip color films which eventually fade towards pink as the dye couplers continue to chemically degrade over time. In order to counteract this inevitable process with modern color films, the three-strip process is essentially [[reverse engineered]] to create [[separation masters]], which are three black and white negatives, one each sensitized for red, green, and blue, that can be reliably used to preserve the color record of modern films. |

||

==Tripack film== |

==Tripack film== |

||

Modern color film is based on the subtractive color system, which basically takes away unwanted colors from white light through layers of subtractive colors within a single strip of film. A subtractive color (also called a " |

Modern color film is based on the subtractive color system, which basically takes away unwanted colors from white light through layers of subtractive colors within a single strip of film. A subtractive color (also called a "[[complementary color]]") is what remains when one of the primary colors (red, green, blue) has been removed from the spectrum. Eastman Kodak's tripack color film incorporated three seperate layers of color sensitive emulsions into one strip of film. Kodachrome was the first commercially successful application of tripack multilayer film, introduced in 1935.<ref name="explore">''Exploring the Color Image'' (1996) Eastman Kodak Publication H-188.</ref> [[Eastmancolor]], released in 1952, was their first one-strip [[35 mm film|35 mm]] negative used in professional filmmaking. In essence, the Technicolor three-color system was incorporated into one film. This rendered the Technicolor three-strip system relatively obsolete, even though the Technicolor system produced colors that were more precise than tripack film and the dye-transfer print would maintain its color much longer than tripack negative (which fades over time, especially with improper storage).<ref name="readfilm" /> Technicolor continued to offer the dye-imbibition print process for one-strip films until 1975, and even briefly revived it in the 1990s and early 2000s. It is still, as of 2006, the most stable color print process yet created, and prints properly cared for are estimated to retain their color and contrast for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years.<ref name="wilhelm">http://www.wilhelm-research.com/pdf/HW_Book_10_of_20_HiRes_v1a.pdf</ref> |

||

==How modern color film works== |

==How modern color film works== |

||

| Line 70: | Line 70: | ||

====Fuji's current (2006) line of color camera negative films:==== |

====Fuji's current (2006) line of color camera negative films:==== |

||

The "85" prefix designates 35 mm stock, the "86" prefix designates 16 mm stock. All stock numbers ending in a "2" are Fuji's Super-F emulsions (1990s) and the stocks ending in "3" are the new Eterna emulsions |

The "85" prefix designates 35 mm stock, the "86" prefix designates 16 mm stock. All stock numbers ending in a "2" are Fuji's Super-F emulsions (1990s) and the stocks ending in "3" are the new Eterna emulsions <ref>Fuji (January 12, 2006). ''[http://www.fujifilmusa.com/JSP/fuji/epartners/MPNewsReleasesDetail.jsp?dbid=NEWS_841903 Fujifilm Expands Eterna Family with the Introduction of Eterna 400, Eterna 250]'' Retrieved July 8, 2006</ref>. Fuji also introduced their Reala film - a color stock with a 4th color emulsion layer, which is also the fastest daylight balanced color motion picture stock ever offered at 500 ISO. |

||

*Eterna |

*Eterna |

||

**Eterna 250D 8563/8663 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

**Eterna 250T 8553/8653 |

|||

**Eterna 400T 8583/8683 |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

*Super-F |

*Super-F |

||

| Line 84: | Line 87: | ||

*Reala |

*Reala |

||

** |

**Reala 500D 8592/8692 |

||

==References== |

==References== |

||

Revision as of 20:47, 7 July 2006

This article discusses the evolution and technology behind color photographic film, with specific focus on motion pictures.

History of Color film

For the history of motion picture film, in general, see 35 mm film

The history of color film is long and complex. Color movies started nearly as early as film itself in 1896 with Thomas Edison's hand-painted Anabelle's Dance made for his Kinetoscope viewers. George Méliès was utilizing a similar hand-painting process for his films, including the early pioneer A Trip to the Moon (1902), which had various parts of the film painted frame-by-frame by twenty-one women in Montreuil[1] in a production-line method.[2] Between 1900 and 1935, dozens of color systems were introduced, some successfully.[3]

Film tinting was a procedure that dyed the whole film base, giving the image a uniform monochromatic color. This process was popular during the 1920s with specific colors employed for certain narrative effects (red for scenes with fire or firelight, blue for night, etc.).[2]

Among the early tinting processes, Pathé Frères invented Pathé color (renamed Pathéchrome in 1929, one of the most accurate and reliable tinting systems that incorporated a series of frame-by-frame stencils, cut by pantograph to correspond to those areas to be tinted in any one of six standard colors[1] by a coloring machine with rollers to color his company's films.[4] After a stencil had been made for the whole film, it was placed into contact with the print to be colored and run at high speed (60 feet per minute) through the coloring (staining) machine. The process was repeated for each set of stencils corresponding to a different color. By 1910 Pathé had over 400 women employed as stencilers in his Vincennes factory. Pathéchrome continued in production through the 1930s.[1]

A similar process called toning comes from dying the silver halide particles in the film. This creates a color effect in the dark areas of the image. Tinting and toning were often applied together.[2]

Eastman Kodak introduced their own system of pre-tinted black-and-white film stocks called Sonochrome in 1929. Sonochrome featured films tinted in sixteen different colors including: Peach-blow, Inferno, Rose Doree, Candle Flame, Sunshine, Purple Haze, Firelight, Fleur de Lis, Azure, Nocturne, Verdante, Acqua Green, Argent and Caprice.[3]

Physics of light and color

The principles on which color photography are based were first proposed by Scottish physicist James Clerk Maxwell in 1855 and finally presented at the Royal Institution of London in 1861. By this time, it was known that light is comprised of a spectrum of different wavelengths which are perceived as different colors as they are absorbed and reflected by natural objects. Maxwell discovered that all natural colors in this spectrum are composed of different combinations of three primary colors - red, green and blue - which when mixed together equally produce white light.[1]

Additive color

The additive color system, also known as two-color, came into popularity because it could be incorporated with black-and-white film stock. The various additive systems entailed the use of color filters on both the photography and projection apparatus. Additive color basically adds lights of the primary colors in various proportions to the projected image. Kinemacolor, first introduced in 1906,[4] a two-color system created in England by Edward R. Turner and George Albert Smith was used for a series of films including the documentary The Durbar at Delhi (1912). In Kinemacolor alternating frames of black-and-white film were photographed at 32 frames per second through either the red or green areas of a rotating filter, and the printed film was projected through the same filter at the same speed. The sense of color was achieved through a combination of speparate red and green alternating images and the viewer's persistance of vision. [2]

Frenchman Louis Dufay developed Dufay Color in the 1930s, which was a reversal film (producing a positive image on the camera original) that used a mosaic of tiny filter elements of the primary colors between the emulsion and base of the film.[4].

The general problem with additive systems was that each layer of color added actually cut down on the overall light being projected onto the screen, resulting in an image that was not sufficiently bright. For this reason, as well as various difficulties in the different methods, additive processes for motion pictures were abandoned about the time of the Second World War, though a variation of the system is employed for most all color video and computer display systems.[2]

Subtractive color

After experimenting with more advanced methods of additive systems (including a camera with two apertures (one with red filter one with green)) Dr. Herbert T. Kalmus and Dr. Donald F. Comstock developed the subtractive color system for Technicolor by utilizing a beam splitter in a specially modified camera to send red and green light waves to separate film negatives. From these negatives two prints were made, which were then dyed (one red-orange the other blue-green[4] and "welded" together back-to-back into a single piece. The first film using this process was Toll of the Sea (1922). Perhaps the most ambitious film made with this process was The Black Pirate, directed by Albert Parker (1926). The system was refined through the incorporation of imbibition, which allowed for the transferring of dyes from both color matricies into a single print - thus avoiding the problems at attaching two prints back-to-back and allowing for multiple prints to be created from a single pair of matricies.[2]

This process was extremely popular for a number of years, but it was a very expensive process (requiring double the cost of film, plus dyes and a type of litho printing) and by 1932 it had nearly been abandonded. This was until a new advancement to create a three-color process. This process utilized a special dichroic beam splitter equipped with two 45-degree prisms in the form of a cube. Light from the lens was deflected by the prisms and split to each expose one of three black and white negatives (one each to record the densities for red, green, and blue). The three negatives were then printed to "matrices" which also completely bleached the image, washing out the silver and leaving only the gelatin record of the image. A "receiver print" consisting of a 50% density print of the black and white negative for the green record strip, and including the soundtrack, was struck and treated with dye mordants to aid in the imbibition process. The matrices for each strip were coated with their complementary dye (yellow, cyan, or magenta), and then each successively brought into high-pressure contact with the receiver, which would imbibe and hold the dyes which collectively were able to render a wider spectrum of colors than the previous technologies.[5] The first film with the three-color (also called three-strip) system was the short film La Cucaracha (1934); the first feature was Becky Sharp (1935).[4] These films and their prints have extremely higher long-term sustainability because both the black and white negatives and the dye-based prints are very resistant to fading, unlike modern one-strip color films which eventually fade towards pink as the dye couplers continue to chemically degrade over time. In order to counteract this inevitable process with modern color films, the three-strip process is essentially reverse engineered to create separation masters, which are three black and white negatives, one each sensitized for red, green, and blue, that can be reliably used to preserve the color record of modern films.

Tripack film

Modern color film is based on the subtractive color system, which basically takes away unwanted colors from white light through layers of subtractive colors within a single strip of film. A subtractive color (also called a "complementary color") is what remains when one of the primary colors (red, green, blue) has been removed from the spectrum. Eastman Kodak's tripack color film incorporated three seperate layers of color sensitive emulsions into one strip of film. Kodachrome was the first commercially successful application of tripack multilayer film, introduced in 1935.[6] Eastmancolor, released in 1952, was their first one-strip 35 mm negative used in professional filmmaking. In essence, the Technicolor three-color system was incorporated into one film. This rendered the Technicolor three-strip system relatively obsolete, even though the Technicolor system produced colors that were more precise than tripack film and the dye-transfer print would maintain its color much longer than tripack negative (which fades over time, especially with improper storage).[3] Technicolor continued to offer the dye-imbibition print process for one-strip films until 1975, and even briefly revived it in the 1990s and early 2000s. It is still, as of 2006, the most stable color print process yet created, and prints properly cared for are estimated to retain their color and contrast for hundreds, perhaps thousands, of years.[7]

How modern color film works

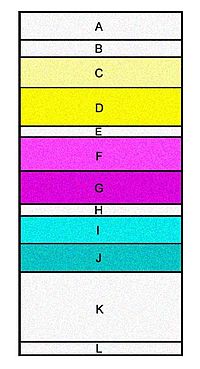

Modern color film is made up of many different layers all working together to create the color image. In color negative films there are three main color layers: the blue record, green record and red record; each made up of two separate layers. Each layer contains silver halide crystals and dye-couplers. A cross-sectional representation of a piece of developed color negative film is at right. Each layer of the film is so thin that the composite of all layers, in addition to the triacetate base and antihaliation backing, is less than .0003" thick.[8]

The three color records are stacked as shown at right with a UV filter on top to keep the non-visible ultraviolet radiation from exposing the silver halide crystals, which are naturally sensitive to UV light. Next, the fast and slow blue sensitive layers, which, when developed, form the latent image. When the exposed silver halide crystal is developed, it is coupled with a dye grain of its complementary color. This forms a dye "cloud" (like a drop of water on a paper towel) and is limited in its growth by developing ingibiting releasing (DIR) couplers, which also serve to refine the sharpness of the processed image by limiting the size of the dye clouds. The dye clouds formed in the blue layer are actually yellow (the opposite or complimentary color to blue).[9] There are two layers to each color; a "fast" and a "slow." The fast layer features larger grains that are more sensitive to light than the slow layer, which has finer grain and is less sensitive to light. Silver halide crystals are naturally sensitive to blue light, so the blue layers are on the top of the film and they are followed immediately by a yellow filter, which stops any more blue light from passing through to the green and red layers and biasing those crystals with extra blue exposure. Next are the red sensitive record (which forms cyan dyes when developed), and at the bottom, the green sensitive record, which forms magenta dyes when developed. Each color is separated by a gelatin layer which prevents silver development in one record from causing unwanted dye formation in another. The bottom of the whole stack is an antihaliation layer that prevents bright light from reflecting off the clear base of the film and passing back through the negative to double-expose the crystals and create "halos" of light around bright spots. In color film this backing is rem-jet, which is a black-pigmented nongelatin layer on the back of the film base and is removed in the developing process.[8]

Eastman Kodak manufacturers film in 54 inch wide rolls. These rolls are then slit into various sizes (65 mm, 35 mm, 16 mm) as needed.

Modern manufacturers of color film for motion picture use

Motion picture film, primarily because of the rem-jet backing, requires a different developer bath than standard color film. The developer necessary is ECN-2 (Eastman Color Negative 2). If motion picture negative is run through a standard C-41 color film developer bath, the rem-jet backing will destroy the intregrity of the developer and, potentially, ruin the film.

There are two main companies manufacturing color film for motion picture use: Eastman Kodak and Fuji Films.

Kodak color motion picture films

In the late 1980s Kodak introduced the T-Grain emulsion, a technological advancement in the shape and makeup of silver halide grains in their films. T-Grain is a tabular silver halide grain that allows for greater overall surface area, resulting in greater light sensitivity with a relatively small grain and a more uniform shape which results in a less overall graininess to the film. This made for sharper and more sensitive films. The T-Grain technology was first employed in Kodak's EXR line of motion picture color negative stocks.[10] This was further refined in 1996 with the Vision line of emulsions, followed by Vision2 in the early 2000s.

Kodak's current (2006) line of color camera negative films:

The prefex "52" designates 35 mm negative size, "72" designates 16 mm. The "T" designates a tungsten (3200K) balanced negative and "D" designates a daylight (5600K) negative. The number preceeding this is the film's speed (ISO).

- Vision

- 5274/7274 Vision 200T

- 5279/7279 Vision 500T

- Vision2

- 5201/7201 Vision2 50D

- 5205/7205 Vision2 250D

- 5212/7212 Vision2 100T

- 5217/7217 Vision2 200T

- 5218/7218 Vision2 500T

- 5229/7229 Vision2 "Expression" 500T

- 7299 Vision2 "HD Color Scan film"

Fuji color motion picture films

Fuji films also integrate tabular grains in their SUFG (Super Unified Fine Grain) films. In their case the SUFG grain is not only tabular, it is hexagonal and consistent in shape throughout the emulsion layers. Like the T-grain, it has a larger surface area in a smaller grain (about 1/3 the size of traditional grain for the same light sensitivity. In 2005 Fuji unveiled their Eterna 500T stock, the first in a new line of advanced emulsions, keeping competitive with Kodak's innovations.

Fuji's current (2006) line of color camera negative films:

The "85" prefix designates 35 mm stock, the "86" prefix designates 16 mm stock. All stock numbers ending in a "2" are Fuji's Super-F emulsions (1990s) and the stocks ending in "3" are the new Eterna emulsions [11]. Fuji also introduced their Reala film - a color stock with a 4th color emulsion layer, which is also the fastest daylight balanced color motion picture stock ever offered at 500 ISO.

- Eterna

- Eterna 250D 8563/8663

- Eterna 250T 8553/8653

- Eterna 400T 8583/8683

- Eterna 500T 8573/8673

- Super-F

- F-64D 8522/8622

- F-125T 8532/8632

- F-250T 8552/8652

- F-250D 8562/8662

- F-500T 8572/8672

- F-400T 8582/8682

- Reala

- Reala 500D 8592/8692

References

- ^ a b c d Cook, David A. (1990) (2nd ed). A History of Narrative Film W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-95553-2.

- ^ a b c d e f Konigsberg, Ira (1987). The Complete Film Dictionary Meridan PAL books. ISBN 0-452-00980-4.

- ^ a b c Monaco, James (1981) (Revised ed) How to Read a Film Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-502806-6.

- ^ a b c d e Katz, Ephraim (1994) (2nd ed). The Film Encyclopedia HarperCollins Press. ISBN0-06-273089-4

- ^ http://www.widescreenmuseum.com/oldcolor/technicolor6.htm

- ^ Exploring the Color Image (1996) Eastman Kodak Publication H-188.

- ^ http://www.wilhelm-research.com/pdf/HW_Book_10_of_20_HiRes_v1a.pdf

- ^ a b Kodak Motion Picture Film (H1) (4th ed). Eastman Kodak Company. ISBN 0-87985-477-4

- ^ Holben, Jay. (April 2000). "Taking Stock" Part 1 of 2. American Cinematographer Magazine ASC Press. pp. 118-130

- ^ Probst, Christopher. (May 2000). "Taking Stock" Part 2 of 2 American Cinematographer Magazine ASC Press. pp. 110-120

- ^ Fuji (January 12, 2006). Fujifilm Expands Eterna Family with the Introduction of Eterna 400, Eterna 250 Retrieved July 8, 2006