Adrenaline: Difference between revisions

Blitterbug (talk | contribs) m Typo (replication of 'flight') |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2014}} |

|||

{{redirect2|Adrenaline|Adrenalin}} |

{{redirect2|Adrenaline|Adrenalin}} |

||

{{drugbox | verifiedrevid = 464189734 |

{{drugbox | verifiedrevid = 464189734 |

||

| Line 50: | Line 51: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

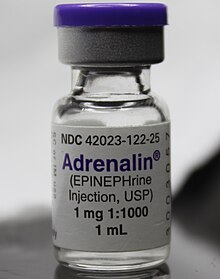

'''Epinephrine''' (also known as '''adrenaline''', '''adrenalin''', or '''4,5-β-[[Hydroxyl|trihydroxy]]-''N''-[[methyl]][[Phenyl|phen]][[Ethyl group|ethyl]][[amine]]''') is a [[hormone]] and a [[neurotransmitter]].<ref>{{cite pmid|6278965}}</ref> |

'''Epinephrine''' (also known as '''adrenaline''', '''adrenalin''', or '''4,5-β-[[Hydroxyl|trihydroxy]]-''N''-[[methyl]] [[Phenyl|phen]] [[Ethyl group|ethyl]] [[amine]]''') is a [[hormone]] and a [[neurotransmitter]].<ref>{{cite pmid|6278965}}</ref> |

||

The investigation of the [[pharmacology]] of epinephrine made a major contribution to the understanding of the [[Autonomic nervous system|autonomic system]] and the function of the [[sympathetic system]]. Epinephrine remains a useful medicine for several emergency indications. This is despite its non-specific action on [[adrenoceptors]] and the subsequent development of multiple selective medicines that target subtypes of the adrenoceptors. |

The investigation of the [[pharmacology]] of epinephrine made a major contribution to the understanding of the [[Autonomic nervous system|autonomic system]] and the function of the [[sympathetic system]]. Epinephrine remains a useful medicine for several emergency indications. This is despite its non-specific action on [[adrenoceptors]] and the subsequent development of multiple selective medicines that target subtypes of the adrenoceptors. |

||

The word adrenaline is used in common parlance to denote increased activation of the sympathetic system associated with the energy and excitement of the [[fight-or-flight response]], even though this is [[Physiology|physiologically]] inaccurate. |

The word adrenaline is used in common parlance to denote increased activation of the sympathetic system associated with the energy and excitement of the [[fight-or-flight response]], even though this is [[Physiology|physiologically]] inaccurate. |

||

| Line 240: | Line 241: | ||

== History == |

== History == |

||

{{Main|History of catecholamine research}} |

{{Main|History of catecholamine research}} |

||

Extracts of the [[adrenal gland]] were first obtained by Polish physiologist [[Napoleon Cybulski]] in 1895. These extracts, which he called ''nadnerczyna'', contained adrenaline and other catecholamines.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jpp.krakow.pl/journal/archive/04_06_s1/articles/01_article.html |title=Polish Thread in the History of Circulatory Physiology |work= |accessdate= |

Extracts of the [[adrenal gland]] were first obtained by Polish physiologist [[Napoleon Cybulski]] in 1895. These extracts, which he called ''nadnerczyna'', contained adrenaline and other catecholamines.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.jpp.krakow.pl/journal/archive/04_06_s1/articles/01_article.html |title=Polish Thread in the History of Circulatory Physiology |work= |accessdate=24 April 2011}}</ref> Japanese chemist [[Jokichi Takamine]] and his assistant Keizo Uenaka independently discovered adrenaline in 1900.<ref>{{cite journal |author=Yamashima T |title=Jokichi Takamine (1854–1922), the samurai chemist, and his work on adrenalin |journal=J Med Biogr |volume=11 |issue=2 |pages=95–102|year=2003 |pmid=12717538}}</ref><ref name="pmid10454061">{{cite journal |author=Bennett M |title=One hundred years of adrenaline: the discovery of autoreceptors |journal=Clin Auton Res |volume=9 |issue=3 |pages=145–59 |year=1999|pmid=10454061 |doi=10.1007/BF02281628}}</ref> In 1901, Takamine successfully isolated and purified the hormone from the adrenal glands of sheep and oxen.<ref>{{cite book |author=Takamine J |title=The isolation of the active principle of the suprarenal gland |work=The Journal of Physiology |publisher=Cambridge University Press |location=Great Britain |year=1901|pages=xxix–xxx |url=http://books.google.com/?id=xVEq06Ym6qcC&pg=RA1-PR29#PRA1-PR29,M1 |isbn= |oclc= |doi=|accessdate=}}</ref> Adrenaline was first synthesized in the laboratory by [[Friedrich Stolz]] and [[Henry Drysdale Dakin]], independently, in 1904.<ref name="pmid10454061"/> |

||

==Adrenaline junkie== |

==Adrenaline junkie== |

||

{{redirect|Adrenaline junkie|the British reality TV series|Jack Osbourne: Adrenaline Junkie}} |

{{redirect|Adrenaline junkie|the British reality TV series|Jack Osbourne: Adrenaline Junkie}} |

||

An ''adrenaline junkie'' is somebody who appears to be addicted to [[Endogeny|endogenous]] epinephrine. The "high" is caused by self-inducing a [[fight-or-flight response]] by intentionally engaging in stressful or risky behavior, which causes a release of epinephrine by the adrenal gland. Adrenaline junkies appear to favor stressful activities for the release of epinephrine as a stress response.<ref>[http://stress.about.com/od/situationalstress/a/adrenaline0528.htm What Is An Adrenaline Junkie? What Can You Do If You Are One?] by Elizabeth Scott, M.S. (updated: |

An ''adrenaline junkie'' is somebody who appears to be addicted to [[Endogeny|endogenous]] epinephrine. The "high" is caused by self-inducing a [[fight-or-flight response]] by intentionally engaging in stressful or risky behavior, which causes a release of epinephrine by the adrenal gland. Adrenaline junkies appear to favor stressful activities for the release of epinephrine as a stress response.<ref>[http://stress.about.com/od/situationalstress/a/adrenaline0528.htm What Is An Adrenaline Junkie? What Can You Do If You Are One?] by Elizabeth Scott, M.S. (updated: 1 November 2007) About.com Health's Disease and Condition content is reviewed by the Medical Review Board.</ref><ref>[http://changingminds.org/explanations/brain/fight_flight.htm Fight-or-flight reaction] - Explanations - Brain -ChangingMinds.org.</ref> Whether or not the positive response is caused specifically by epinephrine is difficult to determine, as [[endorphin]]s are also released during the [[fight-or-flight response]] to such activities.{{citation needed|date=February 2014}} |

||

== References == |

== References == |

||

Revision as of 21:49, 23 March 2014

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | IV, IM, endotracheal, IC, Nasal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Nil (oral) |

| Metabolism | adrenergic synapse (MAO and COMT) |

| Elimination half-life | 2 minutes |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.090 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C9H13NO3 |

| Molar mass | 183.204 g/mol g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Epinephrine (also known as adrenaline, adrenalin, or 4,5-β-trihydroxy-N-methyl phen ethyl amine) is a hormone and a neurotransmitter.[1] The investigation of the pharmacology of epinephrine made a major contribution to the understanding of the autonomic system and the function of the sympathetic system. Epinephrine remains a useful medicine for several emergency indications. This is despite its non-specific action on adrenoceptors and the subsequent development of multiple selective medicines that target subtypes of the adrenoceptors. The word adrenaline is used in common parlance to denote increased activation of the sympathetic system associated with the energy and excitement of the fight-or-flight response, even though this is physiologically inaccurate. [2][3] The influence of adrenaline is mainly limited to a metabolic effect and bronchodilation effect on organs devoid of direct sympathetic innervation.[4][5]

In chemical terms, epinephrine is one of a group of monoamines called the catecholamines. It is produced in some neurons of the central nervous system, and in the chromaffin cells of the adrenal medulla from the amino acids phenylalanine and tyrosine.[6]

Physiology

The adrenal medulla is a minor contributor to total circulating catecholamines, though it contributes over 90% of circulating epinephrine. Little epinephrine is found in other tissues, mostly in scattered chromaffin cells. Following adrenalectomy, epinephrine disappears below the detection limit in the blood stream.[7]

The adrenals contribute about 7% of circulating norepinephrine, most of which is a spill over from neurotransmission with little activity as a hormone.[8][9][10] Pharmacological doses of epinephrine stimulate α1, α2, β1, β2, and β3 adrenoceptors of the sympathetic nervous system. Sympathetic nerve receptors are classified as adrenergic, based on their responsiveness to adrenaline.[11]

The term “adrenergic” is often misinterpreted in that the main sympathetic neurotransmitter is norepinephrine (noradrenaline), rather than epinephrine, as discovered by Ulf von Euler in 1946.[12][13]

Epinephrine does have a β2 adrenoceptor mediated effect on metabolism and the airway, there being no direct neural connection from the sympathetic ganglia to the airway.[14][15][16]

The concept of the adrenal medulla and the sympathetic nervous system being involved in the flight, fight and fright response was originally proposed by Cannon.[17] But the adrenal medulla, in contrast to the adrenal cortex, is not required for survival. In adrenalectomized patients haemodynamic and metabolic responses to stimuli such as hypoglycaemia and exercise remain normal.[18][19]

Epinephrine is important as a central neurotransmitter. In the periphery circulating epinephrine can stimulate the facilitatory noradrenaline pre-synaptic β receptor, though the significance of this is not clear.[20] Beta blockade in man and adrenalectomy in animals show that endogenous epinephrine has significant metabolic effects.[21]

Epinephrine and exercise

The main physiological stimulus to epinephrine secretion is exercise. This was first demonstrated using the dennervated pupil of a cat as an assay,[22] later confirmed using a biological assay on urine samples.[23] Biochemical methods for measuring catecholamines in plasma were published from 1950 onwards.[24] Although much valuable work has been published using fluorimetric assays to measure total catecholamine concentrations, the method is too non-specific and insensitive to accurately determine the very small quantities of epinephrine in plasma. The development of extraction methods and enzyme-isotope derivate radio-enzymatic assays (REA) transformed the analysis down to a sensitivity of 1 pg for epinephrine.[25] Early REA plasma assays indicated that epinephrine and total catecholamines rise late in exercise, mostly when anaerobic metabolism commences.[26][27][28]

During exercise the epinephrine blood concentration rises partially from increased secretion from the adrenal medulla and partly from decreased metabolism because of reduced hepatic blood flow.[29] Infusion of epinephrine to reproduce exercise circulating concentrations of epinephrine in subjects at rest has little haemodynamic effect, other than a small β2 mediated fall in diastolic blood pressure.[30][31] Infusion of epinephrine well within the physiological range suppresses human airway hyper-reactivity sufficiently to antagonist the constrictor effects of inhaled histamine.[32]

A link between what we now know as the sympathetic system and the lung was shown in 1887 when Grossman showed that stimulation of cardiac accelerator nerves reversed muscarine induced airway constriction.[33] In elegant experiments in the dog, where the sympathetic chain was cut at the level of the diaphragm, Jackson showed that there was no direct sympathetic innervation to the lung, but that bronchoconstriction was reversed by release of epinephrine from the adrenal medulla.[34] An increased incidence of asthma has not been reported for adrenalectomized patients; those with a predisposition to asthma will have some protection from airway hyper-reactivity from their corticosteroid replacement therapy. Exercise induces progressive airway dilation in normal subjects that correlates with work load and is not prevented by beta blockade.[35] The progressive dilation of the airway with increasing exercise is mediated by a progressive reduction in resting vagal tone. Beta blockade with propranolol causes a rebound in airway resistance after exercise in normal subjects over the same time course as the bronchoconstriction seen with exercise induced asthma.[36] The reduction in airway resistance during exercise reduces the work of breathing.[37]

Pathology

Increased epinephrine secretion is observed in phaeochromocytoma, hypoglycaemia, myocardial infarction and to a lesser degree in benign essential familial tremor. A general increase in sympathetic neural activity is usually accompanied by increased adrenaline secretion, but there is selectivity during hypoxia and hypoglycaemia, when the ratio of adrenaline to noradrenaline is considerably increased.[38][39][40] Therefore, there must be some autonomy of the adrenal medulla from the rest of the sympathetic system.

For Pheochromocytoma see:[41] [42]

Myocardial infarction is associated with high levels of circulating epinephrine and noepinephrine, particularly in cardiogenic shock.[43][44]

Benign familiar tremor (BFT) is responsive to peripheral β-adrenergic blockers and beta 2 stimulation is known to cause tremor. Patients with BFT were found to have increased plasma epinephrine, but not norepinephrine.[45][46]

Low, or absent, concentrations of epinephrine can be seen in autonomic neuropathy or following adrenalectomy. Failure of the adrenal cortex, as with Addisons disease, can suppress epinephrine secretion as the activity of the synthesing enzyme, phenylethanolamine-N-methyltransferase, depends on the high concentration of cortisol that drains from the cortex to the medulla.[47][48][49]

Pharmacology

Medical uses

Adrenaline is used to treat a number of conditions including: cardiac arrest, anaphylaxis, and superficial bleeding.[50] It has been used historically for bronchospasm and hypoglycemia, but newer treatments for these that are selective for beta2 adrenoceptors, such as salbutamol, a synthetic epinephrine derivative, and dextrose, respectively, are currently preferred. Currently the maximum recommended daily dosage for patients in a dental setting requiring local anesthesia with a peripheral vasoconstrictor is 10 mg/lb of total body weight [50]

Cardiac arrest

Adrenaline is used as a drug to treat cardiac arrest and other cardiac dysrhythmias resulting in diminished or absent cardiac output. Its actions are to increase peripheral resistance via α1receptor-dependent vasoconstriction and to increase cardiac output via its binding to β1 receptors. The goal of reducing peripheral circulation is to increase coronary and cerebral perfusion pressures and therefore increase oxygen exchange at the cellular level. While epinephrine does increase aortic, cerebral, and carotid circulation pressure, it lowers carotid blood flow and end-tidal CO2 or ETCO2 levels. It appears that epinephrine may be improving macrocirculation at the expense of the capillary beds where actual perfusion is taking place.[51] ETCO2 levels have become the marker that predicts the effectiveness of CPR and return of spontaneous circulation.[52] The ability of epinephrine to increase macrocirculatory pressures does not necessarily increase blood flow through end organs. ETCO2 levels might more accurately reflect tissue perfusion instead of perfusion pressure markers.[53]

Epinephrine has not demonstrated its ability to improve tissue perfusion or positively impact long term survival,[54][55] and could be reducing the survival rates of patients in cardiac arrest.[56][57]

Anaphylaxis

Epinephrine/adrenaline is the drug of choice for treating anaphylaxis. Allergy[58] patients undergoing immunotherapy may receive an adrenaline rinse before the allergen extract is administered, thus reducing the immune response to the administered allergen.

Different strengths, doses and routes of administration of epinephrine are used for several medical emergencies. The commonly used Epipen Auto-Injector delivers 0.3 mg epinephrine injection (0.3 mL, 1:1000) is indicated in the emergency treatment of allergic reactions (Type I) including anaphylaxis to stings, contrast agents, medicines or patients with a history of anaphylactic reactions to known triggers. A single dose is recommended for patients who weigh 30 kg or more, repeated if necessary. A lower strength product is available for paediatric use[59] This dose causes vasoconstriction at the site of subcutaneous injection, delaying absorption. The pharmacokinetic profile produces plasma concentrations in the region of 2 nmol/l, a concentration that be also be achieved with the repeated use of an epinephrine inhaler. This concentration is similar to that achieved during intense exercise and is too low to have significant beta 1 adrenoceptor, or alpha vasoconstrictor activity, but has marked beta 2 adrenceptor activity causing a fall in plasma potassium, an elevation in plasma glucose and enhanced finger tremor with additional bronchodilation and bronchoprotection.[60]

The allergic reaction dose of epinephrine (0.3 mg 1/1,000 SC) suppresses the experimentally induced wheal of the wheal and flare response to intradermally injected antigen.[61] This suppression of the wheal is mediated by beta 2 adrenoceptors.[62] The mechanism of the suppression of the edema is to reduce the vascular leak of fluid through the inter-endothelial junction of post capillary venules via beta receptor stimulation on the endothelial surface.[63] Repeated doses, or higher doses, may cause additional microvascular constriction via alpha receptor stimulation, which also suppresses inflammatory edema.[64]

When given intravenously (iv), or intra-muscularly (im), the potency of epinephrine is greatly enhanced. For this reason for refactory anaphylactic shock or cardiac arrest a dilute epinephrine preparation is used of 1/10,000, the iv or im route being used for faster onset of action.[65][66][67] The adult dose for refractory anaphylactic shock is usually 0.1 mg (1:10,000) IV over 5 min and for cardiac arrest 1 mg (1:10,000) as an IV push. When given IV a major mechanism is via alpha adrenoceptor mediated vasoconstriction, increasing central blood pressure, making more selective alpha adrenoceptor agonists an alternative treatment[68][69] Intramuscular injection can be complicated in that the depth of subcutaneous fat varies and may result in subcutaneous injection, or may be injected intravenously in error, or the wrong strength used.[70] Intramuscular injection does give a faster and higher pharmacokinetic profile when compared to SC injection [71]

Because of various expressions of α1 or β2 receptors, depending on the patient, administration of adrenaline may raise or lower blood pressure, depending on whether or not the net increase or decrease in peripheral resistance can balance the positive inotropic and chronotropic effects of adrenaline on the heart, effects that increase the contractility and rate, respectively, of the heart.[citation needed]

The usual concentration for SC or IM injection is 0.3 - 0.5 ml of 1:1,000. It is available in the trade as epipen

Asthma

Adrenaline is also used as a bronchodilator for asthma if specific β2 agonists are unavailable or ineffective.[72]

When given by the subcutaneous or intramuscular routes for asthma, an appropriate dose is 300-500 mcg.[73][74]

Croup

Racemic epinephrine has historically been used for the treatment of croup.[75][76] Racemic adrenaline is a 1:1 mixture of the dextrorotatory (d) and levorotatory (l) isomers of adrenaline.[77] The l- form is the active component.[77] Racemic adrenaline works by stimulation of the α-adrenergic receptors in the airway, with resultant mucosal vasoconstriction and decreased subglottic edema, and by stimulation of the β-adrenergic receptors, with resultant relaxation of the bronchial smooth muscle.[76]

In local anesthetics

Adrenaline is added to injectable forms of a number of local anesthetics, such as bupivacaine and lidocaine, as a vasoconstrictor to slow the absorption and, therefore, prolong the action of the anesthetic agent. Due to epinephrine's vasoconstricting abilities, the use of epinephrine in localized anesthetics also helps to diminish the total blood loss the patient sustains during minor surgical procedures. Some of the adverse effects of local anesthetic use, such as apprehension, tachycardia, and tremor, may be caused by adrenaline. Epinephrine/adrenalin is frequently combined with dental and spinal anesthetics and can cause panic attacks in susceptible patients at a time when they may be unable to move or speak due to twilight drugs.[78]

Autoinjectors

Adrenaline is available in an autoinjector delivery system. Auvi-Qs, Jexts, EpiPens, Emerade, Anapens, and Twinjects all use adrenaline as their active ingredient. Twinject, which is now discontinued, contained a second dose of adrenaline in a separate syringe and needle delivery system contained within the body of the autoinjector. Though both EpiPen and Twinject are trademark names, common usage of the terms is drifting toward the generic context of any adrenaline autoinjector.[citation needed]

Adverse effects

Adverse reactions to adrenaline include palpitations, tachycardia, arrhythmia, anxiety, panic attack, headache, tremor, hypertension, and acute pulmonary edema.[79]

Use is contraindicated in people on nonselective β-blockers, because severe hypertension and even cerebral hemorrhage may result.[80] Although commonly believed that administration of adrenaline may cause heart failure by constricting coronary arteries, this is not the case. Coronary arteries have only β2 receptors, which cause vasodilation in the presence of adrenaline.[81] Even so, administering high-dose adrenaline has not been definitively proven to improve survival or neurologic outcomes in adult victims of cardiac arrest.[82]

Terminology

Epinephrine is the hormone's United States Adopted Name and International Nonproprietary Name, though the more generic name adrenaline is frequently used. The term Epinephrine was coined by the pharmacologist John Abel, who used the name to describe the extracts he prepared from the adrenal glands as early as 1897.[83] In 1901, Jokichi Takamine patented a purified adrenal extract, and called it "adrenalin", which was trademarked by Parke, Davis & Co in the U.S.[83] In the belief that Abel's extract was the same as Takamine's, a belief since disputed, epinephrine became the generic name in the U.S.[83] The British Approved Name and European Pharmacopoeia term for this chemical is adrenaline and is indeed now one of the few differences between the INN and BAN systems of names.[84]

Among American health professionals and scientists, the term epinephrine is used over adrenaline. However, pharmaceuticals that mimic the effects of epinephrine are often called adrenergics, and receptors for epinephrine are called adrenergic receptors or adrenoceptors.

Mechanism of action

| Organ | Effects |

|---|---|

| Heart | Increases heart rate |

| Lungs | Increases respiratory rate |

| Systemic | Vasoconstriction and vasodilation |

| Liver | Stimulates glycogenolysis |

| Systemic | Triggers lipolysis |

| Systemic | Muscle contraction |

As a hormone and neurotransmitter, epinephrine acts on nearly all body tissues. Its actions vary by tissue type and tissue expression of adrenergic receptors. For example, high levels of epinephrine causes smooth muscle relaxation in the airways but causes contraction of the smooth muscle that lines most arterioles.

Epinephrine acts by binding to a variety of adrenergic receptors. Epinephrine is a nonselective agonist of all adrenergic receptors, including the major subtypes α1, α2, β1, β2, and β3.[80] Epinephrine's binding to these receptors triggers a number of metabolic changes. Binding to α-adrenergic receptors inhibits insulin secretion by the pancreas, stimulates glycogenolysis in the liver and muscle, and stimulates glycolysis in muscle.[85] β-Adrenergic receptor binding triggers glucagon secretion in the pancreas, increased adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion by the pituitary gland, and increased lipolysis by adipose tissue. Together, these effects lead to increased blood glucose and fatty acids, providing substrates for energy production within cells throughout the body.[85]

Measurement in biological fluids

Adrenaline may be quantified in blood, plasma, or serum as a diagnostic aid, to monitor therapeutic administration, or to identify the causative agent in a potential poisoning victim. Endogenous plasma adrenaline concentrations in resting adults are normally less than 10 ng/L, but may increase by 10-fold during exercise and by 50-fold or more during times of stress. Pheochromocytoma patients often have plasma adrenaline levels of 1000-10,000 ng/L. Parenteral administration of adrenaline to acute-care cardiac patients can produce plasma concentrations of 10,000 to 100,000 ng/L.[86][87]

Biosynthesis and regulation

Adrenaline is synthesized in the medulla of the adrenal gland in an enzymatic pathway that converts the amino acid tyrosine into a series of intermediates and, ultimately, adrenaline. Tyrosine is first oxidized to L-DOPA, which is subsequently decarboxylated to give dopamine. Oxidation gives norepinephrine. The final step in adrenaline biosynthesis is the methylation of the primary amine of noradrenaline. This reaction is catalyzed by the enzyme phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase (PNMT) which utilizes S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe) as the methyl donor.[88] While PNMT is found primarily in the cytosol of the endocrine cells of the adrenal medulla (also known as chromaffin cells), it has been detected at low levels in both the heart and brain.[89]

Epinephrine and psychology

Epinephrine and emotional response

Every emotional response has a behavioral component, an autonomic component, and a hormonal component. The hormonal component includes the release of epinephrine, an adrenomedullary response that occurs in response to stress and that is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system. The major emotion studied in relation to epinephrine is fear. In an experiment, subjects who were injected with epinephrine expressed more negative and fewer positive facial expressions to fear films compared to a control group. These subjects also reported a more intense fear from the films and greater mean intensity of negative memories than control subjects.[90] The findings from this study demonstrate that there are learned associations between negative feelings and levels of epinephrine. Overall, the greater amount of epinephrine is positively correlated with an arousal state of negative feelings. These findings can be an effect in part that epinephrine elicits physiological sympathetic responses including an increased heart rate and knee shaking, which can be attributed to the feeling of fear regardless of the actual level of fear elicited from the video. Although studies have found a definite relation between epinephrine and fear, other emotions have not had such results. In the same study, subjects did not express a greater amusement to an amusement film nor greater anger to an anger film.[90] Similar findings were also supported in a study that involved rodent subjects that either were able or unable to produce epinephrine. Findings support the idea that epinephrine does have a role in facilitating the encoding of emotionally arousing events, contributing to higher levels of arousal due to fear.[91]

Epinephrine and memory

It has been found that adrenergic hormones, such as epinephrine, can produce retrograde enhancement of long-term memory in humans. The release of epinephrine due to emotionally stressful events, which is endogenous epinephrine, can modulate memory consolidation of the events, insuring memory strength that is proportional to memory importance. Post-learning epinephrine activity also interacts with the degree of arousal associated with the initial coding.[92] There is evidence that suggests epinephrine does have a role in long-term stress adaptation and emotional memory encoding specifically. Epinephrine may also play a role in elevating arousal and fear memory under particular pathological conditions including post-traumatic stress disorder.[91] Overall, the general findings through most studies supports that “endogenous epinephrine released during learning modulate the formation of long-lasting memories for arousing events”.[93] Studies have also found that recognition memory involving epinephrine depends on a mechanism that depends on B-adrenoceptors.[93] Epinephrine does not readily cross the blood-brain barrier, so its effects on memory consolidation are at least partly initiated by B-adrenoceptors in the periphery. Studies have found that sotalol, a B-adrenoceptor antagonist that also does not readily enter the brain, blocks the enhancing effects of peripherally administered epinephrine on memory.[94] These findings suggest that B-adrenoceptors are necessary for epinephrine to have an effect on memory consolidation.

For noradrenaline to be acted upon by PNMT in the cytosol, it must first be shipped out of granules of the chromaffin cells. This may occur via the catecholamine-H+ exchanger VMAT1. VMAT1 is also responsible for transporting newly synthesized adrenaline from the cytosol back into chromaffin granules in preparation for release.[citation needed]

In liver cells, adrenaline binds to the β-adrenergic receptor, which changes conformation and helps Gs, a G protein, exchange GDP to GTP. This trimeric G protein dissociates to Gs alpha and Gs beta/gamma subunits. Gs alpha binds to adenyl cyclase, thus converting ATP into cyclic AMP. Cyclic AMP binds to the regulatory subunit of protein kinase A: Protein kinase A phosphorylates phosphorylase kinase. Meanwhile, Gs beta/gamma binds to the calcium channel and allows calcium ions to enter the cytoplasm. Calcium ions bind to calmodulin proteins, a protein present in all eukaryotic cells, which then binds to phosphorylase kinase and finishes its activation. Phosphorylase kinase phosphorylates glycogen phosphorylase, which then phosphorylates glycogen and converts it to glucose-6-phosphate. [citation needed]

Regulation

The major physiologic triggers of adrenaline release center upon stresses, such as physical threat, excitement, noise, bright lights, and high ambient temperature. All of these stimuli are processed in the central nervous system.[95]

Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and the sympathetic nervous system stimulate the synthesis of adrenaline precursors by enhancing the activity of tyrosine hydroxylase and dopamine-β-hydroxylase, two key enzymes involved in catecholamine synthesis.[citation needed] ACTH also stimulates the adrenal cortex to release cortisol, which increases the expression of PNMT in chromaffin cells, enhancing adrenaline synthesis. This is most often done in response to stress.[citation needed] The sympathetic nervous system, acting via splanchnic nerves to the adrenal medulla, stimulates the release of adrenaline. Acetylcholine released by preganglionic sympathetic fibers of these nerves acts on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, causing cell depolarization and an influx of calcium through voltage-gated calcium channels. Calcium triggers the exocytosis of chromaffin granules and, thus, the release of adrenaline (and noradrenaline) into the bloodstream.[citation needed]

Unlike many other hormones adrenaline (as with other catecholamines) does not exert negative feedback to down-regulate its own synthesis.[96] Abnormally elevated levels of adrenaline can occur in a variety of conditions, such as surreptitious epinephrine administration, pheochromocytoma, and other tumors of the sympathetic ganglia.

Its action is terminated with reuptake into nerve terminal endings, some minute dilution, and metabolism by monoamine oxidase and catechol-O-methyl transferase.

Chemical synthesis

Epinephrine may be synthesized by the reaction of catechol (1) with chloroacetyl chloride (2), followed by reaction with methylamine to give the ketone (4), which is reduced to the desired hydroxy compound (5). The racemic mixture may be separated using tartaric acid.

For isolation from the adrenal glands tissue of livestock:

- J. Takamine, J. Soc. Chem. Ind., 20, 746 (1901).

- J. B. Aldrich, Am. J. Physiol., 5, 457 (1901).

Synthetic production:

- A. F. Stolz, Chem. Ber., 37, 4149 (1904).

- K. R. Payne, Ind. Chem. Chem. Manuf., 37, 523 (1961).

- H. Loewe, Arzneimittel-Forsch., 4, 583 (1954).

- Farbenwerke Meister Lucins & Bruning in Hochst a.M., DE 152814 (1903).

- Farbenwerke Meister Lucins & Bruning in Hochst a.M., DE 157300 (1903).

- Farbenwerke Meister Lucins & Bruning in Hochst a.M., DE 222451 (1908).

- Attention: This template ({{cite doi}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by doi:10.1021/ja01186a024, please use {{cite journal}} (if it was published in a bona fide academic journal, otherwise {{cite report}} with

|doi=10.1021/ja01186a024instead. - D. Flacher, Z. Physiol. Chem., 58, 189 (1908).

History

Extracts of the adrenal gland were first obtained by Polish physiologist Napoleon Cybulski in 1895. These extracts, which he called nadnerczyna, contained adrenaline and other catecholamines.[97] Japanese chemist Jokichi Takamine and his assistant Keizo Uenaka independently discovered adrenaline in 1900.[98][99] In 1901, Takamine successfully isolated and purified the hormone from the adrenal glands of sheep and oxen.[100] Adrenaline was first synthesized in the laboratory by Friedrich Stolz and Henry Drysdale Dakin, independently, in 1904.[99]

Adrenaline junkie

An adrenaline junkie is somebody who appears to be addicted to endogenous epinephrine. The "high" is caused by self-inducing a fight-or-flight response by intentionally engaging in stressful or risky behavior, which causes a release of epinephrine by the adrenal gland. Adrenaline junkies appear to favor stressful activities for the release of epinephrine as a stress response.[101][102] Whether or not the positive response is caused specifically by epinephrine is difficult to determine, as endorphins are also released during the fight-or-flight response to such activities.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 6278965, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=6278965instead. - ^ Editorial (1982). "Stress, hypertension, and the heart: the adrenaline triology". Lancet. 2: 1440–1441.

- ^ Pearce., JMS (2009). "Links between nerves and glands: the story of adrenaline". Advances in Clinical Neuroscience & Rehabilitation. 9: 22–28.

- ^ Celander, O (1954;). "Celander O. The range of control exercised by the "sympathico-adrenal system"". Acta Physiol Scand. 32: uppl 16.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ Warren, JB (1986:). "The adrenal medulla and the airway". Br J Dis Chest. 80 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/0007-0971(86)90002-1. PMID 3004549.

{{cite journal}}: Check date values in:|year=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) CS1 maint: year (link) - ^ von Bohlen und Halbach, O; Dermietzel, R (2006). Neurotransmitters and neuromodulators: handbook of receptors and biological effects. Wiley-VCH. p. 125. ISBN 978-3-527-31307-5.

- ^ Cryer, PE (1980). "Physiology and pathophysiology of the human sympathoadrenal neuroendocrine system". Nejm 1980. 303: 436–444.

- ^ Cryer, PE (1976). "Isotope-derivative measurements of plasma norepinephrine and epinephrine in man". Diabetes. 25 (11): 1071–1082. doi:10.2337/diab.25.11.1071. PMID 825406.

- ^ "Gerich J, et al. Hormonal mechanisms of recovery from insulin-induced hypoglycaemia in man". Am J Physiol 1979. 236: 380–385. 1979.

- ^ Pacak, Karel (2007). Catecholamines and adrenergic receptors. In: Pheochromocytoma Diagnosis, Localization, and Treatment. Chapter 6: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford. p. 62.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Barger, G (1910). "Chemical structure and sympathetic action of amines". J Physiol. 41 (1–2): 19–59. PMC 1513032. PMID 16993040.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Von Euler, US (1946). "A specific sympathomimetic ergone in adrenergic nerve fibres (sympathin) and its relations to adrenaline and nor adrenaline". Acta Physiol Scand. 12: 73–97. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1946.tb00368.x.

- ^ Von Euler, US (1956). "Evidence for the presence of noradrenaline in submicroscopic structures of adrenergic axons". Nature. 177 (4497): 44–45. Bibcode:1956Natur.177...44E. doi:10.1038/177044b0. PMID 13288591.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren, JB. (1986). "The adrenal medulla and the airway". Br J Dis Chest. 80 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1016/0007-0971(86)90002-1. PMID 3004549.

- ^ Twentyman, OP (1981). "Effect of B-blockade on respiratory and metabolic responses to exercise". J Appl Physiol. 51 (4): 788–793. PMID 6795164.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help);|first4=missing|last4=(help);|first5=missing|last5=(help) - ^ Richter, EA; Galbo, H; Christensen, NJ (1981). "Richter EA et al. Control of exercise-induced muscular glycogenolysis by adrenomedullary hormones in rats". J Appl Physiol. 50 (1): 21–26. PMID 7009527.

- ^ Canon, WB. (1931). "Studies on the conditions of activity in endocrine organs xxvii. Evidence that medulliadrenal secretion is not continuous". Am J Physiol. 98: 447–453.

- ^ Cryer, PE (1984). "Roles of glucagon and epinephrine in hypoglycemic and nonhypoglycemic glucose counterregulation in humans". Am J Physiol 247:. 247: E198 – E205.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Hoelzer, DR (1986). "Epinephrine is not critical to prevention of hypoglycemia during exercise in humans". Am J Physiol. 251 (1 Pt 1): E104 – E110. PMID 3524257.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Langer, SZ (1981). "Presynapatic regulation of the release of catecholamines". Pharm Rev. 32 (4): 337–362. PMID 6267618.

- ^ Lunborg, P (1981). "Effect of B-adrenoceptor blockade on exercise performance and metabolism". Clin Sci 1981;61:. 61: 299–305.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Hartman, FA (1922). "The liberation of epinephrine during muscular exercise". Am J Physiol. 62: 225–241.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Von Euler, US (1952). "Excretion of noradrenaline and adrenaline in muscular work". Acta Phys Scand. 26 (2–3): 183–191. doi:10.1111/j.1748-1716.1952.tb00900.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Lund, A (1950). "Simultaneous fluorimetric determinations of adrenaline and noradrenaline in blood". Acta Pharmac Tox;: 137–146.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Johnson, GA (1980). "Single isotope derivatice (radioenzymatic) methods in the measurement of catecholamines". Metabolism 1980;29:suppl:. 29suppl: 1106–1112.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Galbo, HJ (1975). "Glucagon and catecholamine responses to graded and prolonged exercise in man". J Appl Physiol. 38 (1): 70–76. PMID 1110246.

{{cite journal}}:|first2=missing|last2=(help);|first3=missing|last3=(help) - ^ Winder, WW (1978). "Time course of sympathoadrenal adaptation to endurance exercise training in man. J". Apply Physiol. 45: 370–374.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Kindermann, W (1982). "Catecholamines, GH, cortisol, glucagon, insulin and sex hormones in exercise and B-1 blockade". Klin Wochenschrift 1982;60:. 60: 505–512.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Warren, JB (1984). "Adrenaline secretion during exercise". Clin Sci. 66: 47–51.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Fitzgerald, GA (1980). "Circulating adrenaline and blood pressure: the metabolic effects and kinetics of infused adrenaline in man". Eur J Clin Invest 1980. 10 (5): 401–406. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2362.1980.tb00052.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren, JB (1983). "A comparison of the bronchodilator and vassopresser effects of exercise levels of adrenaline in man". Clin Sci. 64 (5): 475–479. PMID 6831836.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren, JB (1984). "Protective effect of circulating epinephrine within the physiological range on the airway response to inhaled histamine in non-asthmatic subjects". J Allergy Clin Immunol. 74 (5): 683–686. doi:10.1016/0091-6749(84)90230-6. PMID 6389647.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Grossman, M (1887). "Das muscarin-lungen-odem". Ztschr f Klin Med. 12: 550–591.

- ^ Jackson, DE (1912). "The pulmonary action of the adrenal glands". J Pharmac Exp Therap. 4: 59–74.

- ^ Kagawa, J (1970). "Effects of brief graded exercise on specific airway conductance in normal subjects". J Appl Physiol. 28 (2): 138–144. PMID 5413299.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren, JB (1984). "Effect of adrenergic and vagal blockade on the normal human airway response to exercise". Clin Sci. 66 (1): 79–85. PMID 6228370.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jennings, SJ (1987). "Airway caliber and the work of breathing in humans". J Appl Physiol. 63 (1): 20–24. PMID 2957350.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Feldberg, W (1934). "The mechanism of the nervous discharge of adrenaline". J Physiol 1934;81:. 81: 286–304.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Burn, JH (1950). "Adrenaline and noradrenaline in the suprarenal medulla after insulin". Br J Pharmacol Chemotherap. 5 (3): 417–423. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1950.tb00591.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Outshoorn, AS (1952). "The hormones of the adrenal medulla and their release". Br J Pharmacol Chemotherap. 7 (4): 605–615. doi:10.1111/j.1476-5381.1952.tb00728.x.

- ^ "Pheochromocytoma". Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Pacak, Karel (2007). Pheochromocytoma Diagnosis, Localization, and Treatment. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Oxford.

- ^ Benedict, CR (1979). "Plasma adrenaline and noradrenaline and dopamine B-hydroxylase activity in myocardial infarction with or without cardiogenic shock". Br Heart J. 1979;42:214–220. 42: 214–220.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Nadeau, RA (1979). "Plasma catecholamines in acute myocardial infarction". Am Heart J. 98 (5): 548–554. doi:10.1016/0002-8703(79)90278-3. PMID 495400.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Larsson, S (1977). "Tremor caused by sympathomimetics is mediated by beta 2-adrenoceptors". Scand J Resp Dis 1977;. 58: 5–10.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Warren, JB (1984). "Sympathetic activity in benign familial tremor". Lancet. 1 (8374): 461–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91804-X. PMID 6142198.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Wurtman, RJ (1972). "Adrenocortical control of the biosynthesis of epinephrine and proteins in the adrenal medulla". Pharmacol Rev. 24 (2): 411–426. PMID 4117970.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jones, A (1955). "Chromaffin tissue in the lizard adrenal gland". Nature 1955::. 175 (4466): 1001–2. Bibcode:1955Natur.175.1001W. doi:10.1038/1751001b0.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Coupland, RE (1953). "On the morphology and adrenaline-noradrenaline content of chromaffin tissue". 9: 194–203.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b "Epinephrine". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- ^ Burnett, Aaron M. (August 2012). "Potential negative effects of epinephrine on carotid blood flow and ETCO2 during active compression–decompression CPR utilizing an impedance threshold device". Resuscitation. 83 (8): 1021–1024. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2012.03.018. PMID 22445865.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Trevino, RP (November 1985). "End-tidal CO2 as a guide to successful cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a preliminary report". Critical Care Medicine. 13 (11): 910–1. doi:10.1097/00003246-198511000-00012. PMID 3931980.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sanders, AB (March 1985). "Expired PCO2 as an index of coronary perfusion pressure". The American journal of emergency medicine. 3 (2): 147–9. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(85)90039-7. PMID 3918548.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Olasveengen, Theresa M. (25 November 2009). "Intravenous Drug Administration During Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest". JAMA. 302 (20): 2222–2229. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1729. PMID 19934423.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Jacobs, Ian G. (September 2011). "Effect of adrenaline on survival in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: A randomised double-blind placebo-controlled trial". Resuscitation. 82 (9): 1138–1143. doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2011.06.029. PMID 21745533.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Roberts, Daniel (1 February 1990). "Early predictors of mortality for hospitalized patients suffering cardiopulmonary arrest" (PDF). Chest. 97 (2): 413–419. doi:10.1378/chest.97.2.413. PMID 2298069.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McCaul, Conán L. (February 2006). "Epinephrine Increases Mortality after Brief Asphyxial Cardiac Arrest in an In Vivo Rat Model". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 102 (2): 542–548. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000195231.81076.88.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Sicherer, Scott H. (2006). Understanding and Managing Your Child's Food Allergy. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8491-8.

- ^ Mylan Specialty L.P.,. "EPIPEN®- epinephrine injection, EPIPEN Jr®- epinephrine injection" (PDF). FDA Product Label. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Warren, JB (1986). "The systemic absorption of inhaled epinephrine". Clin Pharmacol Ther. 40 (6): 673–678. doi:10.1038/clpt.1986.243. PMID 3780129.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren, JB (1988). "Systemic adrenaline attenuates the skin response to antigen and histamine". Clin Allergy. 18 (2): 197–199. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2222.1988.tb02859.x. PMID 2896554.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren, JB (1989). "Importance of beta2-adrenoceptor stimulation in the suppression of intradermal antigen challenge by adrenaline". Br J Clin Pharmacol. 27 (2): 173–177. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.1989.tb05348.x. PMC 1379777. PMID 2565729.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Warren, JB (1993). "Vascular control of inflammatory oedema". Clinical Science. 84 (6): 581–584. PMID 8334803.

- ^ Warren, JB (1993). "Opposing roles of intracellular cAMP in the vascular control of edema formation". FASEB Journal. 7 (14): 1394–1400. PMID 7693536.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ ECC Committee, Subcommittees and Task Forces of the American Heart Association (2005). "2005 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Part 10.6: Anaphylaxis". Circulation. 112 (24 suppl): IV–143–IV–145.

- ^ Neumar, RW (2010). "Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care". Circulation. 122 (18 suppl 3): S729 – S767. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.970988. PMID 20956224.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); horizontal tab character in|coauthors=at position 21 (help); horizontal tab character in|title=at position 52 (help) - ^ Lieberman, P (2010). "The diagnosis and management of anaphylaxis practice parameter: 2010 update". J Allergy Clin Immunol;. 126(3): (3): 477–480. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.06.022.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help); horizontal tab character in|coauthors=at position 30 (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Higgins, DJ (1999). "Methoxamine in the management of severe anaphylaxis". Anaesthesia. 54 (11): 1126. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.1999.01197.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ McBrien, ME (2001). "Use of methoxamine in the resuscitation of epinephrine-resistant electromechanical dissociation". Anaesthesia. 56 (11): 1085–89. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2044.2001.02268-2.x.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Pensylvannia Patient Advisory. "Let's Stop this "Epi"demic!—Preventing Errors with Epinephrine. ". Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- ^ McLean-Tooke, AP (2003). "Adrenaline in the treatment of anaphylaxis: what is the evidence?". BMJ. 327 (7427): 1332–5. doi:10.1136/bmj.327.7427.1332. PMC 286326. PMID 14656845.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ "Asthma Causes, Types, Symptoms, Treatment, Medication, Facts and the Link to Allergies by MedicineNet.com".

- ^ Soar, Perkins, et al (2010) European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 8. Cardiac arrest in special circumstances: Electrolyte abnormalities, poisoning, drowning, accidental hypothermia, hyperthermia, asthma, anaphylaxis, cardiac surgery, trauma, pregnancy, electrocution. Resuscitation. Oct. pp.1400-1433

- ^ Fisher, Brown, Cooke (Eds) (2006) Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee. UK Ambulance Clinical Practice Guidelines.

- ^ Bjornson CL, Johnson DW (2008). "Croup". The Lancet. 371 (9609): 329–339. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60170-1. PMID 18295000.

- ^ a b Thomas LP, Friedland LR (1998). "The cost-effective use of nebulized racemic adrenaline in the treatment of croup". American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 16 (1): 87–89. doi:10.1016/S0735-6757(98)90073-0. PMID 9451322.

- ^ a b Malhotra A, Krilov LR (2001). "Viral Croup". Pediatrics in Review. 22 (1): 5–12. doi:10.1542/pir.22-1-5. PMID 11139641.

- ^ R. Rahn and B. Ball. Local Anesthesia in Dentistry, 3M ESPE AG, ESPE Platz, Seefeld, Germany, 2001, 44 pp.

- ^ About.com - "The Definition of Epinephrine"

- ^ a b Shen, Howard (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 4. ISBN 1-59541-101-1.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12147535, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12147535instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 1522840, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=1522840instead. - ^ a b c Aronson, Jeffrey K (19 February 2000). ""Where name and image meet"—the argument for "adrenaline"". British Medical Journal. 320 (2733): 506–509. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7233.506. PMC 1127537. PMID 10678871.

- ^ Changes to medicines names: BANs to rINNs, Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

- ^ a b Sabyasachi Sircar (2007). Medical Physiology. Thieme Publishing Group. p. 536. ISBN 3-13-144061-9.

- ^ Raymondos, K.; Panning, B.; Leuwer, M.; Brechelt, G.; Korte, T.; Niehaus, M.; Tebbenjohanns, J.; Piepenbrock, S. (2000). "Absorption and hemodynamic effects of airway administration of adrenaline in patients with severe cardiac disease". Ann. Intern. Med. 132 (10): 800–803. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00007. PMID 10819703.

- ^ Baselt, R. (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Foster City, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 545–547. ISBN 0-9626523-7-7.

- ^ Kirshner, Norman (1957). "The Formation of Adrenaline From Noradrenaline". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 24 (3): 658–659. doi:10.1016/0006-3002(57)90271-8. PMID 13436503.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Axelrod, Julius (May 1962). "Purification and Properties of Phenylethanolamine-N-methyl Transferase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 237 (5): 1657–1660.

- ^ a b Mezzacappa, E.S., Katkin, E.S., and Palmer, S.N. (1999). Epinephrine, arousal, and emotion: A new look at two-factor theory. Cognition and Emotion, 13(2), 181-199. doi:10.1080/026999399379320

- ^ a b Mate, T., et al. (2013). Impaired conditioned fear response and startle reactivity in epinephrine-deficient mice. Behavioural Pharmacology, 24(1), 1-9. doi:10.1097/FBP.0b013e32835cf408

- ^ Cahill, L. and Alkire, M.T. (2002). Epinephrine enhancement of human memory consolidation; Interaction with arousal at encoding. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 79(2), 194-198. doi:10.1016/S1074-7427(02)00036-9

- ^ a b Dornelles, A., et al. (2007). Adrenergic enhancement of consolidation of object recognition memory. Neurobiology of Learning and Memory, 88(1), 137-142. doi:10.1016/j.nlm.2007.01.005

- ^ Roozendaal, B., and James, L.M., (2011). Theoretical review: Memory Modulation. Behavioral Neuroscience, 125(6), 797-824. doi:10.1037/a0026187

- ^ Nelson, L.; Cox, M. (2004). Lehninger Principles of Biochemstry (4th ed.). New York: Freeman. p. 908. ISBN 0-7167-4339-6.

- ^ http://www.worldofmolecules.com/emotions/adrenaline.htm

- ^ "Polish Thread in the History of Circulatory Physiology". Retrieved 24 April 2011.

- ^ Yamashima T (2003). "Jokichi Takamine (1854–1922), the samurai chemist, and his work on adrenalin". J Med Biogr. 11 (2): 95–102. PMID 12717538.

- ^ a b Bennett M (1999). "One hundred years of adrenaline: the discovery of autoreceptors". Clin Auton Res. 9 (3): 145–59. doi:10.1007/BF02281628. PMID 10454061.

- ^ Takamine J (1901). The isolation of the active principle of the suprarenal gland. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press. pp. xxix–xxx.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ What Is An Adrenaline Junkie? What Can You Do If You Are One? by Elizabeth Scott, M.S. (updated: 1 November 2007) About.com Health's Disease and Condition content is reviewed by the Medical Review Board.

- ^ Fight-or-flight reaction - Explanations - Brain -ChangingMinds.org.