Little Boy: Difference between revisions

Mrtrollingpants (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

21stCenturyGreenstuff (talk | contribs) Undid revision 457313121 by Mrtrollingpants (talk) RV V |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox Weapon |

{{Infobox Weapon |

||

|name= Little |

|name= Little Boy |

||

|image=[[File:Little boy.jpg|center|300px]] |

|image=[[File:Little boy.jpg|center|300px]] |

||

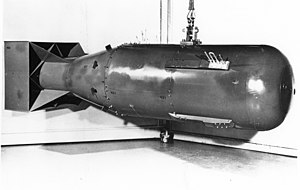

|caption= A post-war "Little Boy" model. |

|caption= A post-war "Little Boy" model. |

||

Revision as of 13:27, 25 October 2011

| Little Boy | |

|---|---|

A post-war "Little Boy" model. | |

| Type | Nuclear weapon |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 9,700 pounds (4,400 kg)[1] |

| Length | 120 inches (3.0 m)[1] |

| Diameter | 28 inches (710 mm)[1] |

| Blast yield | 13–18 kt (54–75 TJ) |

"Little Boy" was the codename of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 by the Boeing B-29 Superfortress Enola Gay, piloted by Colonel Paul Tibbets of the 393rd Bombardment Squadron, Heavy, of the United States Army Air Forces.[2] It was the first atomic bomb to be used as a weapon. The second, the "Fat Man", was dropped three days later on Nagasaki.[3]

The weapon was developed by the Manhattan Project during World War II. It derived its explosive power from the nuclear fission of uranium 235. The Hiroshima bombing was the second artificial nuclear explosion in history, after the Trinity test, and the first uranium-based detonation. Approximately 600 to 860 milligrams of matter in the bomb was converted into the active energy of heat and radiation (see mass-energy equivalence for detail). It exploded with an energy between 13 and 18 kilotons of TNT (54 and 75 TJ) (estimates vary). It has been estimated that 130,000 to 150,000 persons had died by the end of December 1945.[4] Its design was not tested in advance, unlike the more complex plutonium bomb (Fat Man). The available supply of enriched uranium was very small at that time, and it was felt that the simple design of a uranium "gun" type bomb was so sure to work that there was no need to test it at full scale.

Naming

The names for all three atomic bomb design projects during WW II ("Fat Man", "Thin Man", and "Little Boy") were allegedly created by Robert Serber, a former student of Los Alamos director Robert Oppenheimer who worked on the project, according to Serber. According to his later memoirs, he chose them based on their design shapes; the "Thin Man" would be a very long device, and the name came from the Dashiell Hammett detective novel and series of movies by the same name; the "Fat Man" bomb would be round and fat and was named after Sidney Greenstreet's "Kasper Gutman" character in The Maltese Falcon. "Little Boy" would come last and be named only to contrast to the "Thin Man" bomb.[5] The original "Thin Man" had been expected to be as long as 17 feet, but when it was discovered that U-235 would require a slower projectile speed than first measurements had indicated, it was realized that the gun-design could be shortened to 6 feet, and this design was named "Little Boy" in contrast.[6] However, in his memoirs, Paul Tibbets, commander of the 509th Composite Group said the code names were part of an Air Force cover story. According to Tibbets, Project Silverplate, the Air Force program to modify the B-29 to carry atomic bombs, was given the cover story of existing to modify the B-29 into a passenger plane. One plane was allegedly for the use of Winston Churchill, 'the fat man', and the other for Franklin Roosevelt, 'the thin man.'[7]

An extremely large six-ton conventional-explosive bomb developed by the British, operational in mid-1944, had been named the Tallboy, at a length of 21ft (6.35m).

Basic weapon design

The Mk I "Little Boy" was 120 inches (300 cm) in length, 28 inches (71 cm) in diameter and weighed approximately 9,700 pounds (4,400 kg).[1] The design used the gun method to explosively force a hollow sub-critical mass of uranium-235 and a solid target cylinder together into a super-critical mass, initiating a nuclear chain reaction. This was accomplished by shooting one piece of the uranium onto the other by means of chemical explosives. It contained 64 kg (141 lb) of uranium, of which less than a kilogram underwent nuclear fission, and of this mass only 0.6 g (0.021 oz) was transformed into energy.[8][9]

No full test of a gun-type nuclear weapon had occurred before the "Little Boy" device was dropped over Hiroshima. The only test explosion of a nuclear weapon had been of an implosion-type weapon using plutonium as its fissionable material, on July 16, 1945 at the Trinity test. There were several reasons for not testing the "Little Boy" device. Primarily, there was little uranium-235 compared with the relatively large amount of plutonium which, it was expected, could be produced by the Hanford reactors. Additionally, the weapon design was simple enough that it was only deemed necessary to do laboratory tests with the gun-type assembly (known during the war as "tickling the dragon's tail"). Unlike the implosion design, which required sophisticated coordination of shaped explosive charges, the gun-type design was considered almost certain to work.

Although occasionally used in later experimental devices, the design was only used once as a weapon because of the danger of accidental detonation. Little Boy's design was unsafe when compared to modern nuclear weapons, which incorporate safety features to endure various accident scenarios. The main objective of Little Boy was to create a weapon that was absolutely guaranteed to work. Consequently, Little Boy incorporated only basic safety mechanisms, thus an accidental detonation could easily occur during one or more of the following scenarios:

- a crash could drive the hollow "bullet" onto the "target" cylinder resulting in a massive release of radiation, or possibly nuclear detonation.

- an electrical short circuit of some sort.

- the danger of misfire was greater over water. If the force of a crash did not trigger the bomb, water leakage into the system could short it out, possibly leading to detonation. The British Red Beard nuclear weapon also suffered from this design flaw.

- Fire.

- Lightning strike.

Assembly details

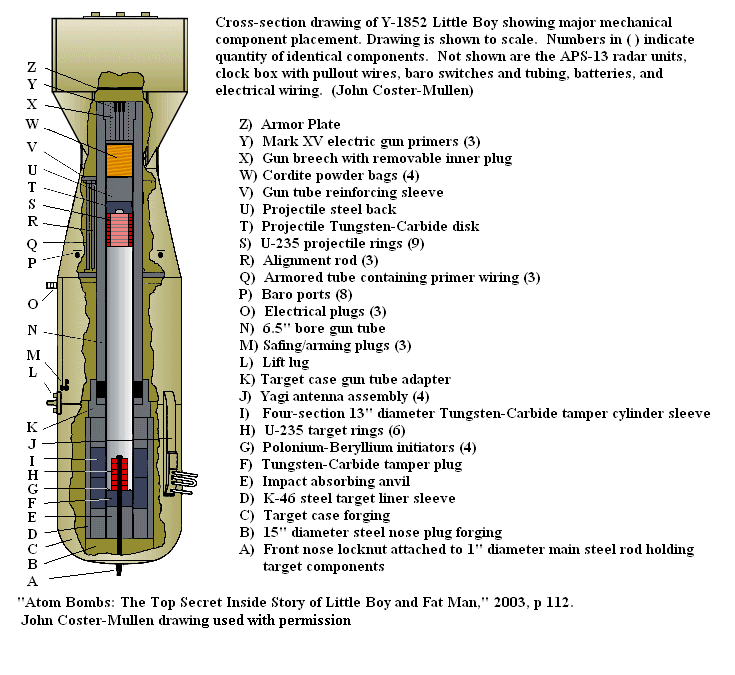

The exact specifications of the "Little Boy" bomb remain classified because they could still be used to create a viable nuclear weapon. Even so, many sources have speculated as to the design, relying on limited photographic evidence, interviews with former Manhattan Project personnel, and piecing together information from declassified sources to reconstruct its internal dimensions.

According to the website Nuclear Weapon Archive,[10][11] inside the weapon, the uranium-235 material was divided into two parts, following the gun principle: the "projectile" and the "target". The projectile was a hollow cylinder with 60% of the total mass (38.5 kg (85 lb)*). It consisted of a stack of 9 uranium rings, each 6.25-inch-diameter (159 mm) with a 4-inch-diameter (100 mm) hole in the center and a total length of 7 inches (180 mm), pressed together into the front end of a thin-walled projectile 16.25 inches (413 mm) long. Filling in the remainder of the space behind these rings in the projectile was a tungsten carbide disc and a steel back. At detonation, the projectile was pushed 42 inches (1,100 mm) down a 72-inch-long (1,800 mm), 6.5-inch (170 mm) smooth-bore gun barrel. The target "insert" was a 4-inch-diameter (100 mm) cylinder, 7-inch (180 mm) long with a 1-inch-diameter (25 mm) hole in the center comprising 40% of the total mass (25.6 kg (56 lb)*). This insert was composed of a stack of 6 washer-like uranium discs somewhat thicker than the projectile rings that were slid over a 1-inch-diameter (25 mm) rod. This rod then extended forward through the tungsten carbide tamper plug, impact absorbing anvil, and nose plug backstop eventually protruding out the front of the bomb casing. This entire target assembly was secured at both ends with locknuts.

When the hollow-front projectile reached the target and slid over the target insert, the assembled super-critical mass of uranium would be completely surrounded by a tamper and neutron reflector of tungsten carbide and steel, both materials having a combined mass of 2,300 kg (5,100 lb).[12] Neutron generators at the base of the projectile would be activated by the impact.

The "L-11" combat Little Boy and the assembled projectile containing the U-235 rings were delivered to Tinian Island on July 26, 1945, by the USS Indianapolis. The six target rings arrived July 28 and 29 on three aircraft. Because the Enola Gay weaponeer "Deak" Parsons was concerned about the possibility of an accidental detonation he did not load the four cordite powder bags into the gun breech until the aircraft was in flight on the mission. Before climbing to high altitude close to the target Parsons' assistant Morris R. Jeppson removed three safety plugs from the electrical connection between the internal battery and the firing mechanism.[13]

Counter-intuitive design

For the first fifty years after 1945, every published description and drawing of the Little Boy mechanism assumed that a small, solid projectile was fired into the center of a larger target.[11] However, critical mass considerations[citation needed] dictated that in Little Boy the larger, hollow piece would be the projectile. For the assembled fissile core to have more than two critical masses of U-235, one of the two pieces would need to have more than one critical mass. To avoid criticality by means of shape, a hole in the center dispersed the mass and increased the surface area, allowing more fission neutrons to escape, preventing further fission and a chain reaction.

It was also important for the larger piece to have minimal contact with the neutron-reflecting tungsten carbide tamper until detonation. Thus only the projectile's back end was in contact with tungsten carbide (see drawing above). The rest of the tungsten carbide surrounded the target cylinder (called the "insert" by designers) with air space between it and the insert. This arrangement packs the maximum amount of fissile material into a gun-assembly design.[14]

Physical effects of the bomb

After being selected in April of 1945, Hiroshima was spared conventional bombing to serve as a pristine target, where the effects of a nuclear bomb on an undamaged city could be observed.[15] While damage could be studied later, the energy yield of the untested Little Boy design could be determined only at the moment of detonation, using instruments dropped by parachute from a plane flying in formation with the one that dropped the bomb. Radio-transmitted data from these instruments indicated a yield of about 15 kilotons.

Comparing this yield to the observed damage produced a rule of thumb called the 5 psi lethal area rule. The number of immediate fatalities will approximately equal the number of people inside the lethal area.

The damage came from three main effects: blast, fire, and radiation.[16]

Blast

The blast from a nuclear bomb is the result of X-ray-heated air (the fireball) sending a shock/pressure wave in all directions at a velocity greater than the speed of sound (aka, the "Mach-Stem"),[17] analogous to thunder generated by lightning. Most knowledge about nuclear weapon urban blast destruction originates from studies of Little Boy at Hiroshima. Data from the explosion at Nagasaki offers less insight, since hilly terrain deflected the blast and generated a more complicated pattern of destruction.

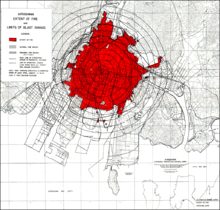

At Hiroshima, severe structural damage to buildings extended about 1 mile (1.6 km) in radius from ground zero, making a circle of destruction 2 miles (3.2 km) in diameter. The blast sent out a hyper-intensified shock wave which travelled at (slightly above) the speed of sound, turning buildings into shrapnel. There was little or no structural damage outside of this one-mile (1.6 km) radius. At one mile (1.6 km), the force of the blast wave was 5 psi, with enough duration to implode houses and reduce them to kindling.

Later test explosions of nuclear weapons with houses and other test structures nearby confirmed that 5 psi (34,000 Pa) is an important threshold. Ordinary urban buildings experiencing it will be crushed, toppled, or gutted by the force of air pressure. The picture at right shows the effects of a nuclear-bomb-generated 5 psi pressure wave on a test structure in Nevada in 1953.

The most important effect of this kind of structural damage was that it created fuel for a firestorm. For this reason, the 5 psi contour defines the lethal area for blast and fire.

Fire

The first effect of the explosion was blinding light, accompanied by radiant heat from the fireball. The Hiroshima fireball was 1,200 feet (370 m) in diameter, with a temperature of 7,200 °F (3,980 °C). Near ground zero, everything flammable burst into flame, glass products and sand melted into molten glass. Contrary to popular opinion, nobody would have been vapourised by the burst - the detonation occured at over 500m altitude and the fireball did not reach the ground. The thermal pulse, while being hot enough to ignite flammable material at distance, was short in duration and these fires went out immediately after the flash or were blown out by the blast wave. The ensuing firestorm was caused by things like damaged fuel or gas pipes and tanks, overturned stoves, destroyed furnaces etc. One famous, anonymous Hiroshima victim left only a "shadow", permanently etched into stone steps near a bank building. Again, converse to popular knowledge, the "shadow" is not the remains or ash of the victim, but in fact it was the area around the shadow, not obscured by the person's silhouette that was lightened by X-rays from the burst, leaving a dark "negative" shadow.[18]

The Hiroshima firestorm was roughly two miles (3.2 km) in diameter, corresponding closely to the severe blast damage zone. (See the USSBS[19] map, right.) Blast-damaged buildings provided fuel for the fire. Structural lumber and furniture were splintered and scattered about. Debris-choked roads obstructed fire fighters. Broken gas pipes fueled the fire, and broken water pipes rendered hydrants useless.

As the map shows, the firestorm jumped natural firebreaks (river channels), as well as prepared firebreaks. The spread of fire stopped only when it reached the edge of the blast-damaged area, encountering less available fuel.

Accurate casualty figures are impossible to determine, because many victims were cremated by the firestorm. For the same reason, the proportion of firestorm victims who survived the blast and died of fire can never be known. Casualty figures are based on the estimated population inside the lethal area when the bomb detonated.

Radiation

Local fallout is dust and ash from a bomb crater, contaminated with radioactive fission products. It falls to earth downwind of the crater and can produce, with radiation alone, a lethal area much larger than that from blast and fire. With an air burst, the fission products rise into the stratosphere, where they dissipate and become part of the global environment. Because Little Boy was an air burst 1,900 feet (580 m) above the ground, there was no bomb crater and no local radioactive fallout.[20]

Intense neutron and gamma radiation came directly from the fireball. Most people close enough to receive lethal doses of direct radiation died in the firestorm before their radiation injuries would have become apparent. Survivors on the edge of the lethal area and beyond suffered injuries from radiation.

Some who initially survived died soon afterward due to acute radiation sickness, but most of the radiation effects are evident only statistically, as increases in the incidence rates of cancer, leukemia and certain non-cancer diseases over the lifetimes of the survivors and their children who were exposed in utero. To date, no radiation-related evidence of heritable diseases have been observed among the survivors' children.[21][22][23]

Development of the bomb

The "Little Boy" bomb was constructed through the Manhattan Project during World War II. Because enriched uranium was known to be fissionable, it was the first approach to bomb development pursued. The vast majority of the work in constructing "Little Boy" came in the form of the isotope enrichment of the uranium necessary for the weapon. Enrichment at Oak Ridge, Tennessee began in February 1943, after many years of research.

The development of the first prototypes and the experimental work started in early 1943, at the time when the Los Alamos Design Laboratory became operational in the framework of the Manhattan Project. Originally gun-type designs were pursued for both a uranium and plutonium weapon (the "Thin Man" design), but in April 1944 it was discovered that the spontaneous fission rate for plutonium was too great to use in a gun-type weapon. In July 1944, almost all research at Los Alamos was redirected to the implosion plutonium weapon. In contrast, the uranium bomb was straight-forward if not trivial to design.

With plutonium found unsuitable for the gun-type design, the team working on the gun weapon (led by A. Francis Birch), faced another problem: the bomb was simple, but they lacked the quantity of uranium-235 necessary for its production. Enough fissile material was not going to be available before mid-1945. Despite this, Birch managed to convince others that this concept was worth pursuing, so that in case of a failure of the plutonium bomb, it would still be possible to use the gun principle. In February 1945, the specifications were completed (model 1850). The bomb, except for the uranium payload, was ready at the beginning of May 1945.

Most of the uranium necessary for the production of the bomb came from the Shinkolobwe mine and was made available thanks to the foresight of the CEO of the High Katanga Mining Union, Edgar Sengier, who had 1000 tons of uranium ore transported to a New York warehouse in 1939. A small amount may have come from a captured German submarine, U-234, after the German surrender in May 1945.[24] Other sources state that at least part of the 1100 tons of uranium ore and uranium oxide captured by US troops in the second half of April 1945 in Stassfurt, Germany, became 235U for the bomb.[25] The majority of the uranium for Little Boy was enriched in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, primarily by means of electromagnetic separation in calutrons and through gaseous diffusion plants, with a small amount contributed by the cyclotrons at Ernest O. Lawrence's Radiation Laboratory. The core of Little Boy contained 64 kg of uranium, of which 50 kg was enriched to 88%, and the remaining 14 kg at 50%. With enrichment averaging 82.68%, it could reach about 2.5 critical masses. "Fat Man" and the Trinity "gadget", by way of comparison, had five critical masses.

Construction and delivery

On July 14, 1945 a train left Los Alamos carrying several "bomb units" (the major non-nuclear parts of a gun-type bomb) together with a single completed uranium projectile; the uranium target was still incomplete. The consignment was delivered to the San Francisco Naval Shipyard at Hunters Point in San Francisco, California.[10] There, two hours before the successful test of Little Boy's plutonium-implosion brother at the Trinity test in New Mexico, the bomb units and the projectile were loaded aboard the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis. Indianapolis steamed at record speed to the airbase at Tinian island in the Mariana Islands, delivering them ten days later on the 26th. (While returning from this mission Indianapolis was sunk by a Japanese submarine, with great loss of life due to delayed rescue.) Also on the 26th the three sections of the uranium target assembly were shipped from Kirtland Air Force Base[10] near Albuquerque, New Mexico in three C-54 Skymaster aircraft operated by the 509th Composite Group's Green Hornet squadron.[26][27] With all the necessary components delivered to Tinian, bomb unit L11 was chosen, and the final Little Boy weapon was assembled and ready by August 1.[10]

Handling the completed Little Boy was particularly dangerous. Once cordite was loaded in the breech, any firing of the explosive would at worst cause a nuclear chain reaction and at best a contamination of the explosion zone. The mere contact of the two uranium masses could have caused an explosion with dire consequences, from a simple "fizzle" explosion to an explosion large enough to destroy Tinian (including the 500 B-29s based there, and their supporting infrastructure and personnel). Water was also a risk, since it could serve as a moderator between the fissile materials and cause a violent dispersal of the nuclear material. The uranium projectile could only be inserted with an apparatus that produced a force of 300,000 newtons (67,000 lbf, over 30 tons). For safety reasons, the weaponeer, Captain William Sterling Parsons, decided to load the bags of cordite only after take-off.

Fuse system

The bomb employed a fusing system that was designed to detonate the bomb at the most destructive altitude. Calculations showed that for the largest destructive effect, the bomb should explode at an altitude of 580 meters (1,900 feet). The resultant fuze design was a three-stage interlock system:[28]

- A timer ensured that the bomb would not explode until at least fifteen seconds after release, one-quarter of the predicted fall time, to ensure safety of the aircraft. The timer was activated when the electrical pullout plugs connecting it to the airplane were pulled loose as the bomb fell, switching it to internal (24V battery) power and starting the timer. At the end of the 15 seconds the batteries then powered the radar system and passed responsibility to the barometric stage.[28]

- The purpose of the barometric stage was to delay activating the radar altimeter firing command circuit until near detonation altitude. A thin metallic membrane was gradually deformed as ambient air pressure increased during descent. The barometric fuze was not considered accurate enough to detonate the bomb at the precise ignition height, because air pressure varies with local conditions. When the bomb reached the design height for this stage (reportedly 2,000 meters) the membrane closed a circuit, activating the circuit between the radar altimeters and the projectile gun. The barometric stage was added because of a worry that external radar signals might detonate the bomb too early.[28]

- Two or more redundant radar altimeters were used to reliably detect descent. When the altimeters sensed the correct height, the firing switch closed, igniting the three BuOrd Mk15, Mod 1 Navy gun primers in the breech plug, which set off the charge consisting of four silk powder bags each containing two pounds of WM slotted-tube cordite. This launched the uranium projectile towards the opposite end of the gun barrel at an eventual muzzle velocity of 1000 feet per second (300 meters per second). Approximately 10 milliseconds later the chain reaction occurred, lasting less than 1 μs. The radar altimeters used were modified U.S. Army Air Corps APS-13 fighter tail warning radars, nicknamed "Archie", originally designed to warn a pilot of another plane approaching from behind.[28][29]

The bombing of Hiroshima

The bomb was armed in flight 31,000 feet (9,400 m) above the city, then dropped at approximately 08:15 (JST) August 6, 1945. After falling for 44.4 seconds, the time and barometric triggers started the firing mechanism. The detonation happened at an altitude of 1,968 feet (600 m). With a yield of 13 to 18 kilotons, it was less powerful than "Fat Man", which was dropped on Nagasaki (21–23 kt). The official yield estimate of "Little Boy" was about 16 kilotons of TNT equivalent in explosive force, i.e. 6.3 × 1013 joules = 63 TJ (tera-joules).[30] However, the damage and the number of victims at Hiroshima were much higher, as Hiroshima was on flat terrain, while the hypocenter of Nagasaki lay in a small valley.

According to figures published in 1945, 66,000 people were killed as a direct result of the Hiroshima blast, and 69,000 were injured to varying degrees.[31]

The U.S. Department of Energy gives this account of the death toll of the bombing of Hiroshima:

"By the end of 1945, because of the lingering effects of radioactive fallout and other after effects, the Hiroshima death toll was probably over 100,000. The five-year death total may have reached or even exceeded 200,000, as cancer and other long-term effects took hold."[32]

The success of the bombing was reported with great enthusiasm in the United States in the days following the attacks. See Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki for discussion of contemporary support vs. opposition to the bombings, on both moral and military grounds.

See also

- Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Debate over the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Enola Gay

- Fat Man

- Fat Man and Little Boy, a 1989 film that re-enacts the Manhattan Project

- The gadget

- List of nuclear weapons

- Manhattan Project

- Nuclear weapon design

- Thin Man nuclear bomb

- Trinity test

- Upshot-Knothole Grable

- White Light/Black Rain: The Destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

References

- ^ a b c d F. G. Gosling (1999). The Manhattan Project: making the atomic bomb. DIANE Publishing. p. 51. ISBN 9780788178801.

- ^ The name Little Boy is alleged on a BBC web site to be a reference to former President Roosevelt.

- ^ Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Damage from the Atomic Bombing", Hiroshima Peace Site, Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|separator=ignored (help) - ^ Robert Serber, Peace & War: Reminiscences of a Life on the Frontiers of Science (New York: Columbia University Press, 1998): 104.

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (1986), The Making of the Atomic Bomb, New York, New York: Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0-671-44133-7, OCLC 13793436 p. 541 iu chapter "Revelations"

{{citation}}: Check|oclc=value (help) - ^ Tibbets, Paul W. The Tibbets' Story. New York: Stein & Day Publishing, 1982. ISBN 0-81287-057-3.

- ^ Glasstone and Dolan, Effects, p. 12–13. When one pound (454 g) of U-235 undergoes complete fission, the yield is 8 kilotons. The 13-to-16-kiloton yield of the Little Boy bomb was therefore produced by the fission no more than two pounds (907 g) of U-235, out of the 141 pounds (64 kg) in the pit. The remaining 139 pounds (63 kg), 98.5% of the total, contributed nothing to the energy yield.

- ^ Chapter I: General Principles of Nuclear Explosions (Sections 1.15, 1.20, 1.21), in The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, Compiled and edited by Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan, Third Edition, on The Trinity Atomic Website.

- ^ a b c d Much of this account is taken from the description of the "Little Boy" by Carey Sublette in Section 8 of his "Nuclear Weapons Frequently Asked Questions". Cite error: The named reference "nukearchive" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b The most recent updates come from John Coster-Mullen's Atom Bombs: The Top Secret Inside Story of Little Boy and Fat Man, 2003 (first printed in 1996), a self-published account based largely on oral histories but which contains, in its extensive appendix, a declassified U.S. government document detailing the exact mass and configuration of the U-235 rings.

- ^ Jeremy Bernstein (October 15, 2007). Nuclear Weapons: What You Need to Know. Cambridge University Press. p. 133. ISBN 052188408X.

a 2,300 kilogram mixture of tungsten carbide and steel was used

- ^ Hiroshima: BBC History of World War II, BBC Television/Tokyo Broadcasting Inc/Discovery Channel 2005.

- ^ This information appeared in 2002 in Racing for the Bomb, by Robert S. Norris, Steerforce Press, p. 409, with the 2001 printing of John Coster-Mullen's Atom Bombs, p. 24, cited as its source.

- ^ Leslie Groves, Now it Can be Told: The Story of the Manhattan Project, 1962. In April 1945, General Groves was instructed to pick targets for the nuclear bombs. Page 267, "To enable us to assess accurately the effects of the bomb, the targets should not have been previously damaged by air raids." Four cities were chosen, including Hiroshima and Kyoto. War Secretary Stimson vetoed Kyoto, and Nagasaki was substituted. Page 275, "When our target cities were first selected, an order was sent to the Army Air Force in Guam not to bomb them without special authority from the War Department."

- ^ Samuel Glasstone and Philip Dolan, The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, Third Edition, 1977, U.S. Dept of Defense and U.S. Dept of Energy.

- ^ Diane Diacon (1984), Residential housing and nuclear attack, Routledge, p. 18, ISBN 9780709908685, retrieved 2011-07-01

- ^ Photograph in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum."Photo"

- ^ United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific War), July 1, 1946, pp. 22-25.

- ^ Glasstone and Dolan, The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, p. 409. "An air burst, by definition, is one taking place at such a height above the earth that no appreciable quantities of surface material are taken up into the fireball. . . the deposition of early fallout from an air burst will generally not be significant. An air burst, however, may produce some induced radioactive contamination in the general vicinity of ground zero as a result of neutron capture by elements in the soil." From p. 36, "at Hiroshima . . . injuries due to fallout were completely absent."

- ^ Frequently Asked Questions, Radiation Effects research foundation.

- ^ Izumi S, Koyama K, Soda M, Suyama A (2003). "Cancer incidence in children and young adults did not increase relative to parental exposure to atomic bombs". Br. J. Cancer. 89 (9): 1709–13. doi:10.1038/sj.bjc.6601322. PMC 2394417. PMID 14583774.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Izumi S, Suyama A, Koyama K (2003). "Radiation-related mortality among offspring of atomic bomb survivors: a half-century of follow-up". Int. J. Cancer. 107 (2): 292–7. doi:10.1002/ijc.11400. PMID 12949810.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Although, responding to a question from Admiral Edwards, General Leslie Groves' 13 August 1945 appointment book entry from the National Archives states, "General advised it wasn't of any help as yet but it will be utilized."

- ^ Rhodes, Richard (1995). Dark Sun: The making of the hydrogen bomb. New York: Touchstone. pp. 160–161. ISBN 0-684-82414-0.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ "Victory"[dead link], Los Alamos National Laboratory's history of the atomic bomb project

- ^ "The Story of the Atomic Bomb", USAF Historical Studies Office

- ^ a b c d Chuck Hansen (September 4, 1995), "Part V, Nuclear Bomb Fusing "Little Boy and Fat Man"", The Swords of Armageddon: U.S. Nuclear Weapons Development since 1945, vol. VIII, pp. 3–45

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|laysummary=ignored (help)[infringing link?] - ^ Letter dated 7 June 1944 to Maj. Gen. L. R. Groves from Robert B. Brode.

- ^ Los Alamos National Laboratory report LA-8819[dead link], The yields of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear explosions by John Malik, September 1985.

- ^ The Manhatten Engineer District (June 29, 1945). "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki". Project Gutenberg Ebook. docstoc.com. p. 3.

{{cite web}}: External link in|publisher= - ^ "The atomic bombing of Hiroshima.[dead link]" United States Department of Energy.

External links

- Footage of Hiroshima Atomic Bomb Attack

- White Light/Black Rain official website documentary film about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- Little Boy description at Carey Sublette's NuclearWeaponArchive.org

- Nuclear Files.org Definition and explanation of 'Little Boy'

- The Nuclear Weapon Archive

- History of Enola Gay

- A little known episode of the Manhattan Project Factitious tests of bombs and problems in aerodynamism

- Development of Little Boy and Fat Man (translated from French)

- Functioning de Little Boy et Fat Man (in French)

- Little Boy : a macabre irony (in French)

- Little Boy 3D Model

- Hiroshima & Nagasaki Remembered information about preparation and dropping the Little Boy bomb

- Models of Hiroshima city center before and after In the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum

- Atomic John: A truck driver uncovers secrets about the first nuclear bombs. Essay and interview with John Coster-Mullen by David Samuels in the New Yorker, December 15, 2008 issue. Coster-Mullen is the author of Atom Bombs: The Top Secret Inside Story of Little Boy and Fat Man, 2003 (first printed in 1996, self-published), considered a definitive text about Little Boy; illustrations from which are used in the Assembly details section above.