Theodore Parker: Difference between revisions

m Added external links |

c/e |

||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

|occupation = |

|occupation = |

||

}} |

}} |

||

'''Theodore Parker''' ([[Lexington, Massachusetts]], August 24, 1810 – [[Florence, Italy]], May 10, 1860) was an [[United States|American]] [[Transcendentalism|Transcendentalist]] and [[Reform movement|reforming]] [[Religious minister|minister]] of the [[American Unitarian Association|Unitarian]] church. A reformer and [[abolitionism|abolitionist]], his |

'''Theodore Parker''' ([[Lexington, Massachusetts]], August 24, 1810 – [[Florence, Italy]], May 10, 1860) was an [[United States|American]] [[Transcendentalism|Transcendentalist]] and [[Reform movement|reforming]] [[Religious minister|minister]] of the [[American Unitarian Association|Unitarian]] church. A reformer and [[abolitionism|abolitionist]], his words and quotes which he popularized would later influence [[Abraham Lincoln]] and [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] |

||

==Biography== |

==Biography== |

||

===Early life=== |

===Early life=== |

||

Theodore Parker was born in [[Lexington, Massachusetts]],<ref name=Hankins143>Hankins, Barry. ''The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2004: 143. ISBN 0-313-31848-4</ref> the youngest child in a large farming family. His grandfather was [[John Parker (captain)|John Parker]], the leader of the Lexington militia at the [[Battle of Lexington]]. |

Theodore Parker was born in [[Lexington, Massachusetts]],<ref name=Hankins143>Hankins, Barry. ''The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2004: 143. ISBN 0-313-31848-4</ref> the youngest child in a large farming family. His grandfather was [[John Parker (captain)|John Parker]], the leader of the Lexington militia at the [[Battle of Lexington]]. Among his colonial Yankee ancestors was [[Thomas Hastings (colonist)|Thomas Hastings]], who came from the East Anglia region of England to the [[Massachusetts Bay Colony]] in 1634, and [[Thomas Parker (deacon)|Deacon Thomas Parker]], who came from England in 1635 and was one of the founders of [[Reading, Massachusetts|Reading]].<ref>Buckminster, Lydia N.H., ''The Hastings Memorial, A Genealogical Account of the Descendants of Thomas Hastings of Watertown, Mass. from 1634 to 1864''. Boston: Samuel G. Drake Publisher (an undated NEHGS photoduplicate of the 1866 edition), 30.</ref><ref>Parker, Theodore, ''John Parker of Lexington and his Descendants, Showing his Earlier Ancestry in America from Dea. Thomas Parker of Reading, Mass. from 1635 to 1893,'' pp. 15-16, 21-30, 34-36, 468-470, Press of Charles Hamilton, Worcester, MA, 1893.</ref><ref>Parker, Augustus G., ''Parker in America, 1630-1910,'' pp. 5, 27, 49, 53-54, 154, Niagara Frontier Publishing Co., Buffalo, NY, 1911.</ref> Most of his family had died<ref name="Grodzins">{{cite web |url= http://www25.uua.org/uuhs/duub/articles/theodoreparker.html |title= Theodore Parker |author= Dean Grodzins |work= Unitarian Universalist Historical Society |quote= }}</ref> by the time Parker was 27, probably due to [[tuberculosis]]. |

||

He was educated privately and through personal study until he attended [[Harvard College]], where he graduated in 1831. He entered the [[Harvard Divinity School]] and graduated in 1836.<ref name=Hankins143/> Parker specialized in a study of German theology. He was drawn to the ideas of [[Samuel Taylor Coleridge|Coleridge]], [[Thomas Carlyle|Carlyle]] and [[Ralph Waldo Emerson|Emerson]]. |

|||

===Career=== |

===Career=== |

||

Parker spoke [[Latin (language)|Latin]], [[Greek language|Greek]], [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]], and [[German (language)|German]]. His journal and letters show that he was acquainted with many other languages, including [[Chaldee]], [[Syriac language|Syriac]], [[Arabic language|Arabic]], [[Coptic language|Coptic]] and [[Ge'ez language|Ethiopic]]. He considered a career in law but his strong [[faith]] led him to theology. Parker held that the soul was [[immortality|immortal]], and came to believe in a God who would not allow lasting harm to any of his flock. His belief in God's mercy made him reject [[Calvinism|Calvinist]] theology as cruel and unreasonable. |

Parker spoke [[Latin (language)|Latin]], [[Greek language|Greek]], [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]], and [[German (language)|German]]. His journal and letters show that he was acquainted with many other languages, including [[Chaldee]], [[Syriac language|Syriac]], [[Arabic language|Arabic]], [[Coptic language|Coptic]] and [[Ge'ez language|Ethiopic]]. He considered a career in law but his strong [[faith]] led him to [[theology]]. Parker held that the soul was [[immortality|immortal]], and came to believe in a God who would not allow lasting harm to any of his flock. His belief in God's mercy made him reject [[Calvinism|Calvinist]] theology as cruel and unreasonable. |

||

Parker studied for a time under [[Convers Francis]], who |

Parker studied for a time under [[Convers Francis]], who preached at Parker's [[ordination]].<ref>Gura, Philip F. ''American Transcendentalism: A History''. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007: 117. ISBN 0-8090-3477-8</ref> In the 1830s, Parker began attending meetings of the [[Transcendental Club]] and became associated with [[Ralph Waldo Emerson]], [[Amos Bronson Alcott]], [[Orestes Brownson]], and several others.<ref>Buell, Lawrence. ''Emerson''. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003: 32–33. ISBN 0-674-01139-2</ref> Unlike Emerson and other Transcendentalists, however, Parker believed the movement was rooted in deeply religious ideas and did not believe it should retreat from religion.<ref name=Hankins143/> |

||

While he started with a strong faith, with time Parker began to ask questions. |

While he started with a strong faith, with time Parker began to ask questions. Learning of the new field of historical [[higher criticism]] of the Bible, then growing in [[Germany]], he came to deny traditional views. Parker was attacked when he denied Biblical miracles and the authority of the Bible and [[Jesus]]. Some felt he was not a Christian; nearly all the pulpits in the Boston area were closed to him,<ref name="Britannica nineteen eleven">{{cite web |url= http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Theodore_Parker |title= Theodore Parker |work= [[Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition]] |quote= }}</ref> and he lost friends. |

||

In 1841, he presented a sermon titled ''A Discourse on the Permanent and Transient in Christianity'', espousing his belief that the scriptures of historic Christianity did not reflect the truth.<ref name=Hankins143/> In 1842 his doubts led him to an open break with orthodox theology: he stressed the immediacy of God and saw the Church as a communion looking upon Christ as the supreme expression of God. Ultimately, he rejected all [[miracle]]s, and saw the Bible as full of contradictions and mistakes. He retained his faith in God but suggested that people experience God intuitively and personally |

In 1841, he presented a sermon titled ''A Discourse on the Permanent and Transient in Christianity'', espousing his belief that the scriptures of historic Christianity did not reflect the truth.<ref name=Hankins143/> In 1842 his doubts led him to an open break with orthodox theology: he stressed the immediacy of God and saw the Church as a communion, looking upon Christ as the supreme expression of God. Ultimately, he rejected all [[miracle]]s, and saw the Bible as full of contradictions and mistakes. He retained his faith in God but suggested that people experience God intuitively and personally. He thought that individual experience was where people should center their religious beliefs.<ref name=Hankins143/> |

||

[[File:Theodore Parker BPL milk glass c1850-crop.jpg|thumb|right|Parker circa 1850]] |

[[File:Theodore Parker BPL milk glass c1850-crop.jpg|thumb|right|Parker circa 1850]] |

||

[[Image:Theodore Parker statue.JPG|thumb|right|Parker's statue in front of the Theodore Parker Church,<ref name="TParkerChurch">{{cite web |url= http://www.tparkerchurch.org/about/history.htm |title= History of the Theodore Parker Church |quote= Established as a Calvinist Protestant church, the congregation adopted a conservative Unitarian theology in the 1830s and followed its minister, Theodore Parker, to a more liberal position in the 1840s. When the First Parish of West Roxbury merged with the Unitarian Church of [[Roslindale, Boston, Massachusetts|Roslindale]] in 1962, the congregation decided to name their new community in memory of Theodore Parker. }}</ref> a Unitarian parish in [[West Roxbury, Massachusetts]].]] |

[[Image:Theodore Parker statue.JPG|thumb|right|Parker's statue in front of the Theodore Parker Church,<ref name="TParkerChurch">{{cite web |url= http://www.tparkerchurch.org/about/history.htm |title= History of the Theodore Parker Church |quote= Established as a Calvinist Protestant church, the congregation adopted a conservative [[Unitarian]] theology in the 1830s and followed its minister, Theodore Parker, to a more liberal position in the 1840s. When the First Parish of West Roxbury merged with the Unitarian Church of [[Roslindale, Boston, Massachusetts|Roslindale]] in 1962, the congregation decided to name their new community in memory of Theodore Parker. }}</ref> a Unitarian parish in [[West Roxbury, Massachusetts]].]] |

||

Parker accepted an invitation from supporters to preach in [[Boston, Massachusetts|Boston]] in January 1845. He preached his first sermon there in February. His supporters organized the 28th Congregational Society of Boston in December and installed Parker as minister in January 1846.<ref name="Grodzins"/> His congregation, which included [[Louisa May Alcott]], [[William Lloyd Garrison]], [[Julia Ward Howe]], and [[Elizabeth Cady Stanton]], grew to 7000.<ref name="Columbia">{{cite web |url= http://www.bartleby.com/65/pa/Parker-T.html |title= Parker, Theodore |work= [[Columbia Encyclopedia]] |quote= }}</ref> |

Parker accepted an invitation from supporters to preach in [[Boston, Massachusetts|Boston]] in January 1845. He preached his first sermon there in February. His supporters organized the 28th Congregational Society of Boston in December and installed Parker as minister in January 1846.<ref name="Grodzins"/> His congregation, which included [[Louisa May Alcott]], [[William Lloyd Garrison]], [[Julia Ward Howe]], and [[Elizabeth Cady Stanton]], grew to 7000.<ref name="Columbia">{{cite web |url= http://www.bartleby.com/65/pa/Parker-T.html |title= Parker, Theodore |work= [[Columbia Encyclopedia]] |quote= }}</ref> |

||

In Boston, |

In Boston, Parker led the movement to combat the stricter [[Fugitive Slave Act]] enacted with the [[Compromise of 1850]]. It required law enforcement and citizens of all states- free states as well as slave states- to assist in the recovery of fugitive slaves. Parker called the law " a hateful statute of kidnappers", and helped organize open resistance to it in Boston. Parker and his followers formed the Committee of Resistance, refusing to assist with the recovery of fugitive slaves, and helping to hide them. For example, they smuggled away [[Ellen and William Craft]] when Georgian slave catchers came to Boston to arrest them. Due to Parker's effort, from 1850 to the onset of the [[American Civil War]] in 1861, only twice were slaves captured in Boston and transported back to the South. On both occasions, Bostonians combatted the actions with mass protests.<ref>Potter, David Morris., and Don E. Fehrenbacher. ''The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861'', New York: Harper & Row, 1976</ref> |

||

Parker was a |

Parker was a patient of William Wesselhoeft, who practiced [[homeopathy]]. He gave the oration at his funeral <ref>[http://homeoint.org/seror/biograph/wesselhoeft.htm William Wesselhoeft (1794-1858) - Pioneers of homeopathy by T. L. Bradford<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> He also supported [[Elizabeth Palmer Peabody]]'s Foreign Library where many intellectuals gathered.<ref>[http://www.concordma.com/magazine/augsept99/peabody2.html Elizabeth Peabody's Foreign Library<!-- Bot generated title -->]</ref> |

||

===Death=== |

===Death=== |

||

[[Image:Theodore Parker's First Gravestone.jpg|thumb|right|Theodore Parker's first [[headstone]].]] |

[[Image:Theodore Parker's First Gravestone.jpg|thumb|right|Theodore Parker's first [[headstone]].]] |

||

[[Image:Cimitero degli inglesi, tomba Theodore Parker.JPG|thumb|right|Theodore Parker's tomb in Florence]] |

[[Image:Cimitero degli inglesi, tomba Theodore Parker.JPG|thumb|right|Theodore Parker's tomb in Florence]] |

||

Parker's ill health forced his retirement in 1859.<ref name="Columbia"/> He developed tuberculosis and departed for [[Florence]], [[Italy]] where he died on May 10, 1860, less than one year before the Union split. He sought refuge in Florence because of his friendship with the Brownings <nowiki>[</nowiki>[[Elizabeth Barrett Browning|Elizabeth Barrett]] and [[Robert Browning]]<nowiki>]</nowiki>, Isa Blagden and F.P. Cobbe, but died scarcely a month following his arrival. |

Parker's ill health forced his retirement in 1859.<ref name="Columbia"/> He developed [[tuberculosis], then without treatment, and departed for [[Florence]], [[Italy]] where he died on May 10, 1860, less than one year before the Union split. He sought refuge in Florence because of his friendship with the Brownings <nowiki>[</nowiki>[[Elizabeth Barrett Browning|Elizabeth Barrett]] and [[Robert Browning]]<nowiki>]</nowiki>, Isa Blagden and F.P. Cobbe, but died scarcely a month following his arrival. A headstone for him at the cemetery by [[Joel Tanner Hart]] was later replaced by one by [[William Wetmore Story]]. Other Unitarians buried in this cemetery include [[Thomas Southwood Smith]] and [[Richard Hildreth]]. [[Fanny Trollope]], who is also buried here, wrote the first anti-slave novel and Hildreth wrote the second. Both books were used by [[Harriet Beecher Stowe]] for ''[[Uncle Tom's Cabin]].'' [[Frederick Douglass]] came straight from the railroad station to visit Parker's tomb.<ref>Douglass, Frederick. ''Life and Times of Frederick Douglass'', 1893. NY: Library of America, reprint, 1994:1015</ref> |

||

==Legacy and honors== |

|||

*[[Frances Power Cobbe|Frances P. Cobbe]] collected and published his writings in 14 volumes. |

|||

Parker's grave is in the [[English Cemetery, Florence]].<ref name="Santini">{{cite web |url= http://www.florin.ms/americantombs.html |title= American Tombs in Florence's English Cemetery |author= Official guidebook written by Pastore Luigi Santini, published by the Administration of the Cimitero agli Allori in 1981 }}</ref><ref>{{Find a Grave|grid=4974}}</ref> |

Parker's grave is in the [[English Cemetery, Florence]].<ref name="Santini">{{cite web |url= http://www.florin.ms/americantombs.html |title= American Tombs in Florence's English Cemetery |author= Official guidebook written by Pastore Luigi Santini, published by the Administration of the Cimitero agli Allori in 1981 }}</ref><ref>{{Find a Grave|grid=4974}}</ref> |

||

==Social criticism and beliefs== |

==Social criticism and beliefs== |

||

As Parker's early biographer John White Chadwick wrote, Parker was involved with almost all of the reform movements of the time: "peace, [[temperance movement|temperance]], education, the condition of women, penal legislation, [[prison reform|prison discipline]], the moral and mental destitution of the rich, the physical destitution of the poor" though none became "a dominant factor in his experience" with the exception of his antislavery views.<ref>Gura, Philip F. ''American Transcendentalism: A History''. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007: 248. ISBN 0-8090-3477-8</ref> Parker's [[abolitionism]] became his most controversial stance, at a time when the American union was beginning to split over [[slavery]].<ref name="Teed">{{cite news |url= http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3837/is_200107/ai_n8989233 |title= " A Brave Man's Child |

As Parker's early biographer John White Chadwick wrote, Parker was involved with almost all of the reform movements of the time: "peace, [[temperance movement|temperance]], education, the condition of women, penal legislation, [[prison reform|prison discipline]], the moral and mental destitution of the rich, the physical destitution of the poor" though none became "a dominant factor in his experience" with the exception of his antislavery views.<ref>Gura, Philip F. ''American Transcendentalism: A History''. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007: 248. ISBN 0-8090-3477-8</ref> Parker's [[abolitionism]] became his most controversial stance, at a time when the American union was beginning to split over [[slavery]].<ref name="Teed">{{cite news |url= http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qa3837/is_200107/ai_n8989233 |title= " A Brave Man's Child: Theodore Parker and the Memory of the American Revolution" |author= Paul E. Teed |work= [http://www.wsc.ma.edu/mhj/ ''Historical Journal of Massachusetts''] Summer 2001 issue |quote= Theodore Parker's 1845 pilgrimage to Lexington was a defining moment in the career of one of New England's most influential antislavery activists. Occurring as it did in the very midst of the national crisis over Texas annexation, Parker's mystical connection with the memory of his illustrious revolutionary ancestor emerged as the bedrock of his identity as an abolitionist.<br /> “While other abolitionists frequently claimed the revolutionary tradition for their cause, Parker's antislavery vision also rested upon a deep sense of filial obligation to the revolutionaries themselves. | year=2001}}</ref> He wrote the scathing ''[[To a Southern Slaveholder]]'' in 1848, as the abolition crisis was heating up. |

||

Parker defied slavery<ref name="Lockard">{{cite web |url= http://antislavery.eserver.org/treatises/slavepower/ |title= ''The Slave Power'' |work= [[EServer.org]] |publisher= [[Digital library|Digitized]] in [[XHTML]], [[Portable Document Format|PDF]] and [[Microsoft Office Word]] by the Antislavery Literature Project |quote= First collected edition of the antislavery writings and speeches of abolitionist Theodore Parker. ([[Boston]]: [[American Unitarian Association]], 1910.) Editor: [http://www.worldcatlibraries.org/search?q=au%3AJames+Kendall+Hosmer&qt=hot_author James Kendall Hosmer] (1837-1927), professor of history at [[Johns Hopkins University]], [http://www.ihaystack.com/authors/h/james_kendall_hosmer/00012429_the_last_leaf_observations_during_seventyfive_years_/00012429_english_iso88591_p006.htm president] of the [[American Library Association]]. }}</ref> and advocated violating the [[Fugitive Slave Law of 1850]], a controversial part of the [[Compromise of 1850]] which required the return of escaped slaves to their owners. Parker worked with many fugitive slaves, some of whom were among Parker's congregation. As in the case of William and Ellen Craft,<ref name="Stephen">{{cite web |url= http://www.secondunitarianomaha.org/sermons.cgi?id=58 |title= Theodore Parker, Slavery, and the Troubled Conscience of the Unitarians |author= Charles Stephen |work= |date= 25 August 2002 |quote= }}</ref> |

Parker defied slavery<ref name="Lockard">{{cite web |url= http://antislavery.eserver.org/treatises/slavepower/ |title= ''The Slave Power'' |work= [[EServer.org]] |publisher= [[Digital library|Digitized]] in [[XHTML]], [[Portable Document Format|PDF]] and [[Microsoft Office Word]] by the Antislavery Literature Project |quote= First collected edition of the antislavery writings and speeches of abolitionist Theodore Parker. ([[Boston]]: [[American Unitarian Association]], 1910.) Editor: [http://www.worldcatlibraries.org/search?q=au%3AJames+Kendall+Hosmer&qt=hot_author James Kendall Hosmer] (1837-1927), professor of history at [[Johns Hopkins University]], [http://www.ihaystack.com/authors/h/james_kendall_hosmer/00012429_the_last_leaf_observations_during_seventyfive_years_/00012429_english_iso88591_p006.htm president] of the [[American Library Association]]. }}</ref> and advocated violating the [[Fugitive Slave Law of 1850]], a controversial part of the [[Compromise of 1850]] which required the return of escaped slaves to their owners. Parker worked with many fugitive slaves, some of whom were among Parker's congregation. As in the case of William and Ellen Craft,<ref name="Stephen">{{cite web |url= http://www.secondunitarianomaha.org/sermons.cgi?id=58 |title= Theodore Parker, Slavery, and the Troubled Conscience of the Unitarians |author= Charles Stephen |work= |date= 25 August 2002 |quote= }}</ref> he hid them in his home. Although he was indicted for his actions, he was never convicted.<ref name="Britannica nineteen eleven"/> |

||

During the undeclared war in [[Kansas]] (see [[Bleeding Kansas]] and [[Origins of the American Civil War]]) prior to the |

During the undeclared war in [[Kansas]] (see [[Bleeding Kansas]] and [[Origins of the American Civil War]]) prior to the outbreak of the [[American Civil War]], Parker supplied money for [[weapon]]s for free state [[militia]]s. As a member of the [[Secret Six]], he supported the abolitionist [[John Brown (abolitionist)|John Brown]], whom many considered a [[terrorism|terrorist]]. After Brown's arrest, Parker wrote a public letter, "John Brown's Expedition Reviewed," defending his actions and the right of slaves to kill their masters. |

||

==Legacy== |

==Legacy== |

||

Boston's Unitarian leadership opposed Parker to the end, but younger ministers admired him for his attacks on traditional ideas, his fight for a free faith and pulpit, and his very public stances on social issues such as slavery. The Unitarian Universalists now refer to him as "a canonical figure—the model of a prophetic minister in the American Unitarian tradition."<ref name="Grodzins"/> |

Boston's Unitarian leadership opposed Parker to the end, but younger ministers admired him for his attacks on traditional ideas, his fight for a free faith and pulpit, and his very public stances on social issues such as slavery. The Unitarian Universalists now refer to him as "a canonical figure—the model of a prophetic minister in the American Unitarian tradition."<ref name="Grodzins"/> |

||

In 1850, Parker used the phrase, "A democracy,— of all the people, by all the people, for all the people;"<ref name="Bartleby">{{cite web |url= http://www.bartleby.com/100/459.html |title= "The American Idea:" speech at N.E. Anti-Slavery Convention, Boston |author= Theodore Parker |work= [[Bartleby.com]] |date= 29 May 1850 |quote= A democracy,—that is a government of all the people, by all the people, for all the people; of course, a government of the principles of eternal justice, the unchanging law of God; for shortness’ sake I will call it the idea of Freedom. }}</ref> which later influenced [[Abraham Lincoln]]'s [[Gettysburg Address]]. Parker might have developed his phrase from [[John Wycliffe| John Wycliffe's]] |

In 1850, Parker used the phrase, "A democracy,— of all the people, by all the people, for all the people;"<ref name="Bartleby">{{cite web |url= http://www.bartleby.com/100/459.html |title= "The American Idea:" speech at N.E. Anti-Slavery Convention, Boston |author= Theodore Parker |work= [[Bartleby.com]] |date= 29 May 1850 |quote= A democracy,—that is a government of all the people, by all the people, for all the people; of course, a government of the principles of eternal justice, the unchanging law of God; for shortness’ sake I will call it the idea of Freedom. }}</ref> which later influenced [[Abraham Lincoln]]'s [[Gettysburg Address]]. Parker might have developed his phrase from [[John Wycliffe| John Wycliffe's]] prologue to the first English translation of the Bible.<ref>{{cite web | title=Wikiquote |url= http://en.wikiquote.org/wiki/John_Wycliffe | accessdate=2010-09-12 }}</ref><ref>{{Cite book | title=The American Monthly Review of Reviews |url= http://books.google.com/books?id=7hCmMq85tOoC&pg=PA336&lpg=PA336&dq=Wycliffe+%22by+all+the+people+for+all+the+people%22&source=bl&ots=PSn2htyYxN&sig=q4Ral2YAOcgV-cxNXmW5kE9V_AA&hl=en&ei=VdeMTNvdHsLflgeAodVg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=3&sqi=2&ved=0CB8Q6AEwAg#v=onepage&q=Wycliffe%20%22by%20all%20the%20people%20for%20all%20the%20people%22&f=false | accessdate=2010-09-12 }}</ref> |

||

Parker predicted the success of the abolitionist cause: "I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice." Theodore Parker"<ref>{{ cite web | last=Manker-Seale | first=Susan | title=The Moral Arc of the Universe: Bending Toward Justice | url=http://www.uucnwt.org/sermons/TheMoralArcOfTheUniverse%201-15-06.html | date=2006-01-15 | accessdate=2008-02-29 }}</ref> [[Martin Luther King, Jr.]] made these words famous a century later in his speech at the Lincoln Memorial. |

|||

In August 2010, President [[Barack Obama]]'s [[Oval Office]] was remodeled |

In August 2010, President [[Barack Obama]]'s [[Oval Office]] was remodeled. Its beige carpet is bordered by five quotes. Two of the quotes, attributed to Lincoln and King, were inspired by the language of Parker, as noted above.<ref>{{ cite news | last=Stiehm | first=Jamie | title=Oval Office rug gets history wrong | url=http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/09/03/AR2010090305100.html | date=2010-09-04 | accessdate=2010-09-04 | work=The Washington Post}}</ref> |

||

==Further reading== |

==Further reading== |

||

Revision as of 16:47, 9 March 2011

Theodore Parker | |

|---|---|

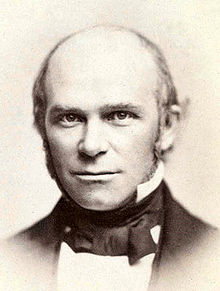

Theodore Parker circa 1855 | |

| Born | August 24, 1810 |

| Died | May 10, 1860 (aged 49) |

| Resting place | English Cemetery, Florence |

Theodore Parker (Lexington, Massachusetts, August 24, 1810 – Florence, Italy, May 10, 1860) was an American Transcendentalist and reforming minister of the Unitarian church. A reformer and abolitionist, his words and quotes which he popularized would later influence Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King, Jr.

Biography

Early life

Theodore Parker was born in Lexington, Massachusetts,[1] the youngest child in a large farming family. His grandfather was John Parker, the leader of the Lexington militia at the Battle of Lexington. Among his colonial Yankee ancestors was Thomas Hastings, who came from the East Anglia region of England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634, and Deacon Thomas Parker, who came from England in 1635 and was one of the founders of Reading.[2][3][4] Most of his family had died[5] by the time Parker was 27, probably due to tuberculosis.

He was educated privately and through personal study until he attended Harvard College, where he graduated in 1831. He entered the Harvard Divinity School and graduated in 1836.[1] Parker specialized in a study of German theology. He was drawn to the ideas of Coleridge, Carlyle and Emerson.

Career

Parker spoke Latin, Greek, Hebrew, and German. His journal and letters show that he was acquainted with many other languages, including Chaldee, Syriac, Arabic, Coptic and Ethiopic. He considered a career in law but his strong faith led him to theology. Parker held that the soul was immortal, and came to believe in a God who would not allow lasting harm to any of his flock. His belief in God's mercy made him reject Calvinist theology as cruel and unreasonable.

Parker studied for a time under Convers Francis, who preached at Parker's ordination.[6] In the 1830s, Parker began attending meetings of the Transcendental Club and became associated with Ralph Waldo Emerson, Amos Bronson Alcott, Orestes Brownson, and several others.[7] Unlike Emerson and other Transcendentalists, however, Parker believed the movement was rooted in deeply religious ideas and did not believe it should retreat from religion.[1]

While he started with a strong faith, with time Parker began to ask questions. Learning of the new field of historical higher criticism of the Bible, then growing in Germany, he came to deny traditional views. Parker was attacked when he denied Biblical miracles and the authority of the Bible and Jesus. Some felt he was not a Christian; nearly all the pulpits in the Boston area were closed to him,[8] and he lost friends.

In 1841, he presented a sermon titled A Discourse on the Permanent and Transient in Christianity, espousing his belief that the scriptures of historic Christianity did not reflect the truth.[1] In 1842 his doubts led him to an open break with orthodox theology: he stressed the immediacy of God and saw the Church as a communion, looking upon Christ as the supreme expression of God. Ultimately, he rejected all miracles, and saw the Bible as full of contradictions and mistakes. He retained his faith in God but suggested that people experience God intuitively and personally. He thought that individual experience was where people should center their religious beliefs.[1]

Parker accepted an invitation from supporters to preach in Boston in January 1845. He preached his first sermon there in February. His supporters organized the 28th Congregational Society of Boston in December and installed Parker as minister in January 1846.[5] His congregation, which included Louisa May Alcott, William Lloyd Garrison, Julia Ward Howe, and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, grew to 7000.[10]

In Boston, Parker led the movement to combat the stricter Fugitive Slave Act enacted with the Compromise of 1850. It required law enforcement and citizens of all states- free states as well as slave states- to assist in the recovery of fugitive slaves. Parker called the law " a hateful statute of kidnappers", and helped organize open resistance to it in Boston. Parker and his followers formed the Committee of Resistance, refusing to assist with the recovery of fugitive slaves, and helping to hide them. For example, they smuggled away Ellen and William Craft when Georgian slave catchers came to Boston to arrest them. Due to Parker's effort, from 1850 to the onset of the American Civil War in 1861, only twice were slaves captured in Boston and transported back to the South. On both occasions, Bostonians combatted the actions with mass protests.[11]

Parker was a patient of William Wesselhoeft, who practiced homeopathy. He gave the oration at his funeral [12] He also supported Elizabeth Palmer Peabody's Foreign Library where many intellectuals gathered.[13]

Death

Parker's ill health forced his retirement in 1859.[10] He developed [[tuberculosis], then without treatment, and departed for Florence, Italy where he died on May 10, 1860, less than one year before the Union split. He sought refuge in Florence because of his friendship with the Brownings [Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning], Isa Blagden and F.P. Cobbe, but died scarcely a month following his arrival. A headstone for him at the cemetery by Joel Tanner Hart was later replaced by one by William Wetmore Story. Other Unitarians buried in this cemetery include Thomas Southwood Smith and Richard Hildreth. Fanny Trollope, who is also buried here, wrote the first anti-slave novel and Hildreth wrote the second. Both books were used by Harriet Beecher Stowe for Uncle Tom's Cabin. Frederick Douglass came straight from the railroad station to visit Parker's tomb.[14]

Legacy and honors

- Frances P. Cobbe collected and published his writings in 14 volumes.

Parker's grave is in the English Cemetery, Florence.[15][16]

Social criticism and beliefs

As Parker's early biographer John White Chadwick wrote, Parker was involved with almost all of the reform movements of the time: "peace, temperance, education, the condition of women, penal legislation, prison discipline, the moral and mental destitution of the rich, the physical destitution of the poor" though none became "a dominant factor in his experience" with the exception of his antislavery views.[17] Parker's abolitionism became his most controversial stance, at a time when the American union was beginning to split over slavery.[18] He wrote the scathing To a Southern Slaveholder in 1848, as the abolition crisis was heating up.

Parker defied slavery[19] and advocated violating the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, a controversial part of the Compromise of 1850 which required the return of escaped slaves to their owners. Parker worked with many fugitive slaves, some of whom were among Parker's congregation. As in the case of William and Ellen Craft,[20] he hid them in his home. Although he was indicted for his actions, he was never convicted.[8]

During the undeclared war in Kansas (see Bleeding Kansas and Origins of the American Civil War) prior to the outbreak of the American Civil War, Parker supplied money for weapons for free state militias. As a member of the Secret Six, he supported the abolitionist John Brown, whom many considered a terrorist. After Brown's arrest, Parker wrote a public letter, "John Brown's Expedition Reviewed," defending his actions and the right of slaves to kill their masters.

Legacy

Boston's Unitarian leadership opposed Parker to the end, but younger ministers admired him for his attacks on traditional ideas, his fight for a free faith and pulpit, and his very public stances on social issues such as slavery. The Unitarian Universalists now refer to him as "a canonical figure—the model of a prophetic minister in the American Unitarian tradition."[5]

In 1850, Parker used the phrase, "A democracy,— of all the people, by all the people, for all the people;"[21] which later influenced Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address. Parker might have developed his phrase from John Wycliffe's prologue to the first English translation of the Bible.[22][23]

Parker predicted the success of the abolitionist cause: "I do not pretend to understand the moral universe; the arc is a long one, my eye reaches but little ways; I cannot calculate the curve and complete the figure by the experience of sight; I can divine it by conscience. And from what I see I am sure it bends towards justice." Theodore Parker"[24] Martin Luther King, Jr. made these words famous a century later in his speech at the Lincoln Memorial.

In August 2010, President Barack Obama's Oval Office was remodeled. Its beige carpet is bordered by five quotes. Two of the quotes, attributed to Lincoln and King, were inspired by the language of Parker, as noted above.[25]

Further reading

- Chadwick, John White. Theodore Parker: Preacher and Reformer. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1900.

- Dirks, John Edward. The Critical Theology of Theodore Parker, New York: Columbia University Press, 1948 (reprinted 1970)

References

- ^ a b c d e Hankins, Barry. The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2004: 143. ISBN 0-313-31848-4

- ^ Buckminster, Lydia N.H., The Hastings Memorial, A Genealogical Account of the Descendants of Thomas Hastings of Watertown, Mass. from 1634 to 1864. Boston: Samuel G. Drake Publisher (an undated NEHGS photoduplicate of the 1866 edition), 30.

- ^ Parker, Theodore, John Parker of Lexington and his Descendants, Showing his Earlier Ancestry in America from Dea. Thomas Parker of Reading, Mass. from 1635 to 1893, pp. 15-16, 21-30, 34-36, 468-470, Press of Charles Hamilton, Worcester, MA, 1893.

- ^ Parker, Augustus G., Parker in America, 1630-1910, pp. 5, 27, 49, 53-54, 154, Niagara Frontier Publishing Co., Buffalo, NY, 1911.

- ^ a b c Dean Grodzins. "Theodore Parker". Unitarian Universalist Historical Society.

- ^ Gura, Philip F. American Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007: 117. ISBN 0-8090-3477-8

- ^ Buell, Lawrence. Emerson. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003: 32–33. ISBN 0-674-01139-2

- ^ a b "Theodore Parker". Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition.

- ^ "History of the Theodore Parker Church".

Established as a Calvinist Protestant church, the congregation adopted a conservative Unitarian theology in the 1830s and followed its minister, Theodore Parker, to a more liberal position in the 1840s. When the First Parish of West Roxbury merged with the Unitarian Church of Roslindale in 1962, the congregation decided to name their new community in memory of Theodore Parker.

- ^ a b "Parker, Theodore". Columbia Encyclopedia.

- ^ Potter, David Morris., and Don E. Fehrenbacher. The Impending Crisis, 1848-1861, New York: Harper & Row, 1976

- ^ William Wesselhoeft (1794-1858) - Pioneers of homeopathy by T. L. Bradford

- ^ Elizabeth Peabody's Foreign Library

- ^ Douglass, Frederick. Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, 1893. NY: Library of America, reprint, 1994:1015

- ^ Official guidebook written by Pastore Luigi Santini, published by the Administration of the Cimitero agli Allori in 1981. "American Tombs in Florence's English Cemetery".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Theodore Parker at Find a Grave

- ^ Gura, Philip F. American Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007: 248. ISBN 0-8090-3477-8

- ^ Paul E. Teed (2001). "" A Brave Man's Child: Theodore Parker and the Memory of the American Revolution"". Historical Journal of Massachusetts Summer 2001 issue.

Theodore Parker's 1845 pilgrimage to Lexington was a defining moment in the career of one of New England's most influential antislavery activists. Occurring as it did in the very midst of the national crisis over Texas annexation, Parker's mystical connection with the memory of his illustrious revolutionary ancestor emerged as the bedrock of his identity as an abolitionist.

"While other abolitionists frequently claimed the revolutionary tradition for their cause, Parker's antislavery vision also rested upon a deep sense of filial obligation to the revolutionaries themselves.{{cite news}}: External link in|work=|work=(help) - ^ "The Slave Power". EServer.org. Digitized in XHTML, PDF and Microsoft Office Word by the Antislavery Literature Project.

First collected edition of the antislavery writings and speeches of abolitionist Theodore Parker. (Boston: American Unitarian Association, 1910.) Editor: James Kendall Hosmer (1837-1927), professor of history at Johns Hopkins University, president of the American Library Association.

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - ^ Charles Stephen (25 August 2002). "Theodore Parker, Slavery, and the Troubled Conscience of the Unitarians".

- ^ Theodore Parker (29 May 1850). ""The American Idea:" speech at N.E. Anti-Slavery Convention, Boston". Bartleby.com.

A democracy,—that is a government of all the people, by all the people, for all the people; of course, a government of the principles of eternal justice, the unchanging law of God; for shortness' sake I will call it the idea of Freedom.

- ^ "Wikiquote". Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ^ The American Monthly Review of Reviews. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ^ Manker-Seale, Susan (2006-01-15). "The Moral Arc of the Universe: Bending Toward Justice". Retrieved 2008-02-29.

- ^ Stiehm, Jamie (2010-09-04). "Oval Office rug gets history wrong". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

External links

- Works by Theodore Parker at Project Gutenberg

- Links to Theodore Parker biographies, works, quotations, articles, etc.

- "Primitive Christianity" on University of Nebraska–Lincoln (UNL) digital commons. Originally published in The Dial for January 1842. Reprinted from The Critical and Miscellaneous Writings of Theodore Parker (Boston: James Munroe and Company, 1843), pp. 222–247.

- Parker review (1840) of D. F. Strauss's Life of Jesus on UNL digital commons. Published originally in the Christian Examiner for April, 1840. Reprinted from Crit. and Misc. Writings pp. 248–308.

- Caleb Crain, "The Good Boy; or, Is Christ Necessary?", a review-essay of Dean Grodzins's American Heretic: Theodore Parker and Transcendentalism

- Theodore Parker Church in West Roxbury, Massachusetts

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - Descendants of Thomas Hastings website

- Descendants of Thomas Hastings on Facebook