Mac operating systems: Difference between revisions

162.84.154.124 (talk) |

m →'Classic' Mac OS (1984-2002): quotes |

||

| Line 32: | Line 32: | ||

* The newer [[Mac OS X]] (the "X" is pronounced ''ten'', as the Roman numeral). Mac OS X incorporates elements of [[BSD Unix]], [[OpenStep]], and [[Mac OS 9]]. Its low-level [[Unix]]-based foundation, [[Darwin (operating system)|Darwin]], is [[free software]] / [[open source software]]. |

* The newer [[Mac OS X]] (the "X" is pronounced ''ten'', as the Roman numeral). Mac OS X incorporates elements of [[BSD Unix]], [[OpenStep]], and [[Mac OS 9]]. Its low-level [[Unix]]-based foundation, [[Darwin (operating system)|Darwin]], is [[free software]] / [[open source software]]. |

||

=== |

=== "Classic" Mac OS (1984-2002)=== |

||

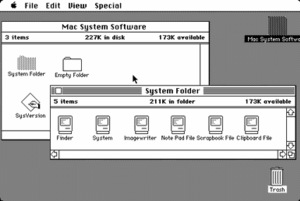

[[Image:Apple Macintosh Desktop.png|right|thumb|300px|Original 1984 Mac OS desktop]] |

[[Image:Apple Macintosh Desktop.png|right|thumb|300px|Original 1984 Mac OS desktop]] |

||

{{mainarticle|Mac OS history}} |

{{mainarticle|Mac OS history}} |

||

The |

The "classic" Mac OS is characterized by its total lack of a [[command line]]; it is a completely graphical operating system. Heralded for its ease of use, it is also criticized for its singletasking (in early versions) or [[cooperative multitasking]] (in later versions), very limited [[Mac OS memory management|memory management]], lack of [[protected memory]], and susceptibility to conflicts among "extensions" that extend the operating system, providing additional functionality (such as networking) or support for a particular device. Some extensions may not work properly together, or work only when loaded in a particular order. Troubleshooting Mac OS extensions can be a time-consuming process of [[trial and error]]. |

||

Mac OS originally used the [[Macintosh File System]] (MFS), a [[flat file]] system with only one [[kludge]]d level of folders. This was replaced by the [[Hierarchical File System]] (HFS), which had a true [[directory]] tree. Both file systems are otherwise compatible. |

Mac OS originally used the [[Macintosh File System]] (MFS), a [[flat file]] system with only one [[kludge]]d level of folders. This was replaced by the [[Hierarchical File System]] (HFS), which had a true [[directory]] tree. Both file systems are otherwise compatible. |

||

Revision as of 22:13, 21 December 2005

| File:Mac OS 9 screenshot 2.jpg A screenshot of Mac OS 9 | |

| Developer | Apple Computer |

|---|---|

| OS family | Classic Mac OS |

| Working state | Discontinued, still used by some |

| Source model | Closed source |

| Latest release | 9.2.2 / 12/5/2002 |

| Latest preview | 15.3 RC[1] (January 21, 2025) |

| Kernel type | Monolithic, later Nanokernel |

| Default user interface | Apple platinum (beginning with Mac OS 8) |

| License | Proprietary |

| Official website | n/a |

Mac OS, which stands for Macintosh Operating System, is a range of graphical user interface-based operating systems developed by Apple Computer for their Macintosh computers. The original Mac OS is often credited for popularizing the graphical user interface successfully. It was first introduced in 1984 with the original Macintosh, the Macintosh 128K.

Apple deliberately played down the existence of the operating system in the early years of the Macintosh to help make the machine appear more user-friendly and to distance it from other operating systems such as MS-DOS, which were portrayed as arcane and technically challenging. Apple wanted Macintosh to be portrayed as a system "for the rest of us". Therefore the term "Mac OS" didn't really exist until it was officially used during the mid-1990s. The term has since been applied to all versions of the Mac system software prior to this as a handy way to refer to it when discussing it in context with other operating systems.

Earlier versions of the Mac OS were compatible only with m68k-based Macintoshes, while later versions were also compatible with the PowerPC (PPC) architecture.

Versions

The Macintosh operating system initially consisted of two pieces of software, called "System" and "Finder", each with its own version number. They were bundled for upgrades as "System Software" with a single version number for each combination. This was formally shortened to "System" (and the component version numbers synchronised) with "System 6". System 7.5.1 was the first to include the Mac OS logo (a blue variation of a smiley face), and Mac OS 7.6 was the first to be named "Mac OS" (to ensure that users would still identify it with Apple, even when used in "clones" from other companies).

Until the advent of the later PowerPC G3-based systems, significant parts of the system were stored in physical ROM on the motherboard. The initial purpose of this was to avoid using up the limited storage of floppy disks on system support, given that the early Macs had no hard disk. (Only one model of Mac was ever actually bootable using the ROM alone, the 1991 Mac Classic model.) This architecture also helped to ensure that only Apple computers (and later licensed clones with the copyright-protected ROMs) could run Mac OS.

The Mac OS can be divided into two families of operating systems:

- "Classic" Mac OS, the system which shipped with the first Macintosh in 1984 and its descendants, culminating with Mac OS 9.

- The newer Mac OS X (the "X" is pronounced ten, as the Roman numeral). Mac OS X incorporates elements of BSD Unix, OpenStep, and Mac OS 9. Its low-level Unix-based foundation, Darwin, is free software / open source software.

"Classic" Mac OS (1984-2002)

The "classic" Mac OS is characterized by its total lack of a command line; it is a completely graphical operating system. Heralded for its ease of use, it is also criticized for its singletasking (in early versions) or cooperative multitasking (in later versions), very limited memory management, lack of protected memory, and susceptibility to conflicts among "extensions" that extend the operating system, providing additional functionality (such as networking) or support for a particular device. Some extensions may not work properly together, or work only when loaded in a particular order. Troubleshooting Mac OS extensions can be a time-consuming process of trial and error.

Mac OS originally used the Macintosh File System (MFS), a flat file system with only one kludged level of folders. This was replaced by the Hierarchical File System (HFS), which had a true directory tree. Both file systems are otherwise compatible.

Most file systems used with DOS, Unix, or other operating systems treat a file as simply a sequence of bytes, requiring an application to know which bytes represented what type of information. By contrast, MFS and HFS gave files two different "forks". The data fork contained the same sort of information as other file systems, such as the text of a document or the bitmaps of an image file. The resource fork contained other structured data such as menu definitions, graphics, sounds, or code segments. A file might consist only of resources with an empty data fork, or only a data fork with no resource fork. A text file could contain its text in the data fork and styling information in the resource fork, so that an application which didn't recognize the styling information could still read the raw text. On the other hand, these forks provided a challenge to interoperability with other operating systems; copying a file from a Mac to a non-Mac system would strip it of its resource fork.

Mac OS X (2001-present)

Mac OS X brought Unix-style memory management and pre-emptive multitasking to the Mac platform. It is based on the Mach kernel and the BSD implementation of UNIX, which were incorporated into NeXTSTEP, the object-oriented operating system developed by Steve Jobs's NeXT company. The new memory management system allowed more programs to run at once and virtually eliminated the possibility of one program crashing another. It is also the second Macintosh operating system to include a command line (the first is the now-discontinued A/UX, which supported classic Mac OS applications on top of a UNIX kernel), although it is never seen unless the user launches a terminal emulator.

However, since these new features put higher demands on system resources, Mac OS X only officially supported the PowerPC G3 and newer processors, and now has even higher requirements (the additional requirement of built-in FireWire (IEEE 1394), as of Mac OS X v10.4). Even then, it runs somewhat slowly on older G3 systems for many purposes.

As of 2005, every update to Mac OS X since the original public beta has had the atypical quality of being perceptibly more responsive than the version it replaced, the opposite to the trend of most operating systems. As noted by John Siracusa of Ars Technica:

- For over three years now, Mac OS X has gotten faster with every release — and not just "faster in the experience of most end users", but faster on the same hardware. This trend is unheard of among contemporary desktop operating systems. [1]

This could, however, be attributed to the relative immaturity of the OS, and the speed gains have diminished as OS X has matured. Some reports regarding Mac OS X 10.4 suggested that it seemed similar to version 10.3 in responsiveness, or even slower at times.

Mac OS X includes a compatibility layer for running older Mac applications, the Classic Environment. This runs a full copy of the older Mac OS, version 9.1 or later, in a Mac OS X process. Most well-written "classic" applications function properly under this environment, but compatibility is only assured if the software was written to be unaware of the actual hardware, and to interact solely with the operating system. The Classic Environment will be eliminated in the x86 version of OS X, Leopard, though it will remain in the Power PC builds of the OS.

Users of the original Mac OS generally upgraded to Mac OS X, but a few criticized it as being more difficult and less user-friendly than the original Mac OS, for the lack of certain features that had not been re-implemented in the new OS, or for being slower on the same hardware (especially older hardware), or other, sometimes serious incompatibilities with the older OS. Because drivers (for printers, scanners, tablets, etc.) written for the older Mac OS are not compatible with Mac OS X, and due to the lack of OS X support for older Apple machines, a significant number of Macintosh users have continued using the older OS. By 2005, it is reported that almost all users of systems capable of running Mac OS X are so doing, with only a small percentage still running the classic Mac OS.

'Classic' Mac OS technologies

A few of these live on in Mac OS X, but many are defunct:

- Chooser: tool for accessing network resources (e.g., enabling AppleTalk) and selecting printers; descended from an earlier "Choose Printer" Desk Accessory (defunct since Mac OS X)

- ColorSync: technology for color matching (still in use)

- Desk Accessories: small "helper" apps that could be run concurrently with any other app, prior to the advent of MultiFinder and System 7 (defunct since System 7)

- Finder: the interface for browsing the filesystem and launching applications (still in use)

- Mac OS memory management: how the Mac managed RAM and virtual memory before the switch to Unix (defunct since Mac OS X)

- Mac-Roman: character set (still in use)

- MultiFinder: support for multiple simultaneous processes (defunct. Supplanted by the default Finder in System 7)

- PlainTalk: speech synthesis and speech recognition technology (still in use, although the proprietary powered microphone interface bearing the same name was phased out with the 'Blue and White' PowerMac G3s in 1999)

- PowerPC emulation of Motorola 68000: how the Mac handled the architectural transition from CISC to RISC (see Mac 68K emulator) (defunct since Mac OS X. Future versions of Mac OS X may emulate the PowerPC on Intel chips in a similar manner, however. See Rosetta)

- QuickDraw: the imaging model which first provided mass-market WYSIWYG (mostly defunct on Mac OS X, where Quartz technology has supplanted Quickdraw. However, Quickdraw still works as of Mac OS X 10.4)

- QuickTime: support for A/V import and playback (still in use)

Project Star Trek

One interesting historical aspect of the classic Mac OS was a relatively unknown secret prototype Apple started work on in 1992, code-named Project Star Trek. The goal of this project was to create a version of Mac OS that would run on Intel-compatible x86 personal computers. It was short lived, being cancelled only one year later in 1993 due to political infighting, though its team was able to get the Macintosh Finder and some basic applications, like QuickTime, running smoothly on a PC.

Although the Star Trek software was never released, third-party Macintosh emulators, such as vMac, Basilisk II, and Executor, eventually made it possible to run the classic Mac OS on x86 PCs. These emulators were restricted to emulating the 68000 line of processors, and as such couldn't run versions of the Mac OS newer than 8.1, which required PowerPC processors. Recently, the PearPC emulator has appeared, which is capable of emulating the PowerPC processors required by newer versions of the Mac OS (like Mac OS X). Unfortunately, it is still in the early stages and, like many emulators, tends to run much slower than a native OS would.

Another PPC emulator is SheepShaver, which has been around since 1998 for the BeOS platform, but in 2002 was open sourced with porting efforts beginning to get it to run on other platforms. Although it is capable of emulating a PowerPC processor, it can only emulate up to Mac OS 9.0.4 because it does not emulate a memory management unit.

In April 2002, eWeek reported a rumor that Apple had a version of Mac OS X running on x86 processors, code-named Marklar. The idea behind Marklar was to keep Mac OS X running on an alternate platform should Apple become unsatisfied with the progress of the PowerPC platform. [2] The rumor was confirmed by Apple's CEO Steve Jobs in June 2005, when he announced that future Macintosh products will run on Intel processors starting in 2006. After pre-release x86-based Macs were released to developers, a copy of the x86-based version of Mac OS X was leaked onto the Internet, and hackers managed to get it to run on non-Apple x86-based PCs.

Apple's plans to fully port Mac OS X from IBM's PowerPC processors to Intel's "x"86 processors include Rosetta, which (roughly) translates G3 instructions to Pentium instructions. For applications in active development, Apple's latest version of Xcode [3] permits an application to be built for both the G5 and Intel processors simultaneously. This is similar to making a "fat binary" in the mid-1990's, which would hold both "680x0" and PowerPC instructions during Apple's transition to the PowerPC architecture.

Mac OS X requires an Intel Pentium 4 or AMD Athlon 64 processor, as it utilizes SSE, SSE2, and SSE3 instructions.

A/UX

In 1988, Apple released its first UNIX based OS, named A/UX.

This was an operating system that seamlessly integrated the Mac OS look and feel with the power and flexibility of UNIX. Since it was before the advent of PowerPC and therefore had to run on the Motorola 68000 processor, it was not very competitive for its time. A/UX had most of its success in sales to the Federal government of the United States, where UNIX was a requirement that Mac OS could not meet.

See also

- Mac OS history

- Mac OS X history

- Mac OS X Server

- List of Macintosh software

- Operating system advocacy

- Comparison of operating systems

External links

- folklore.org a site with anecdotes by the creators of the first Macintosh

- Mac OS X official site

- ^ Clover, Juli (January 21, 2025). "Apple Seeds macOS Sequoia 15.3 Release Candidate to Developers". MacRumors. Retrieved January 22, 2025.