Reelin: Difference between revisions

m Citation maintenance. Formatted: journal, volume. You can use this bot yourself! Please report any bugs. |

m => Cite Journal with Wikipedia template filling (partial), great original refs |

||

| Line 40: | Line 40: | ||

Besides this important role in the early period, reelin continues to work in the adult brain. It modulates the [[synaptic plasticity]] by enhancing [[Long-term potentiation|LTP]] induction and maintenance.<!-- |

Besides this important role in the early period, reelin continues to work in the adult brain. It modulates the [[synaptic plasticity]] by enhancing [[Long-term potentiation|LTP]] induction and maintenance.<!-- |

||

--><ref name="LTP1">Weeber, |

--><ref name="LTP1">{{cite journal |author=Weeber EJ, Beffert U, Jones C, ''et al'' |title=Reelin and ApoE receptors cooperate to enhance hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning |journal=J. Biol. Chem. |volume=277 |issue=42 |pages=39944–52 |year=2002 |month=October |pmid=12167620 |doi=10.1074/jbc.M205147200 |url=}}W</ref><ref name="LTP2">{{cite journal |author=D'Arcangelo G |title=Apoer2: a reelin receptor to remember |journal=Neuron |volume=47 |issue=4 |pages=471–3 |year=2005 |month=August |pmid=16102527 |doi=10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.001 |url=}}</ref> It also stimulates dendrite development<!-- |

||

--><ref name="Niu_2004">Niu S, Renfro A, Quattrocchi CC, Sheldon M, |

--><ref name="Niu_2004">{{cite journal |author=Niu S, Renfro A, Quattrocchi CC, Sheldon M, D'Arcangelo G |title=Reelin promotes hippocampal dendrite development through the VLDLR/ApoER2-Dab1 pathway |journal=Neuron |volume=41 |issue=1 |pages=71–84 |year=2004 |month=January |pmid=14715136 |doi= |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0896627303008195}}</ref><!-- |

||

--> and regulates the continuing migration of [[neuroblast]]s generated in [[adult neurogenesis]] sites like [[subventricular zone|subventricular]] and [[subgranular zone]]s. |

--> and regulates the continuing migration of [[neuroblast]]s generated in [[adult neurogenesis]] sites like [[subventricular zone|subventricular]] and [[subgranular zone]]s. |

||

| Line 60: | Line 60: | ||

Mutant mice provide insight into the underlying molecular mechanisms of the development of the [[Central nervous system|CNS]]. These spontaneous mutations were first identified by scientists interested in motor behavior, and it proved relatively easy to screen [[littermate]]s for mice that showed difficulties moving around the cage. A number of such mice were found and given descriptive names such as reeler, weaver, lurcher, nervous, and staggerer. |

Mutant mice provide insight into the underlying molecular mechanisms of the development of the [[Central nervous system|CNS]]. These spontaneous mutations were first identified by scientists interested in motor behavior, and it proved relatively easy to screen [[littermate]]s for mice that showed difficulties moving around the cage. A number of such mice were found and given descriptive names such as reeler, weaver, lurcher, nervous, and staggerer. |

||

The "[[reeler]]" mouse was first described in the [[1951]] edition of [[Journal of Genetics]] by [[Douglas Scott Falconer]].<ref name="falconer"/> Histopathological studies in the 1960's revealed that the reeler cerebellum is dramatically decreased in size and the normal laminar organization found in several brain regions is disrupted.<ref name="hamburgh"> Hamburgh M |

The "[[reeler]]" mouse was first described in the [[1951]] edition of [[Journal of Genetics]] by [[Douglas Scott Falconer]].<ref name="falconer"/> Histopathological studies in the 1960's revealed that the reeler cerebellum is dramatically decreased in size and the normal laminar organization found in several brain regions is disrupted.<ref name="hamburgh">{{cite journal |author=Hamburgh M |title=Analysis of the postnatal developmental effects of "reeler", a neurological mutation in mice. A study in developmental genetics |journal=Dev. Biol. |volume=19 |issue= |pages=165–85 |year=1963 |month=October |pmid=14069672 |doi= |url=}}</ref> 1970's brought the discovery of cellular layers inversion in the mice neocortex<ref name="caviness">{{cite journal |author=Caviness VS |title=Patterns of cell and fiber distribution in the neocortex of the reeler mutant mouse |journal=J. Comp. Neurol. |volume=170 |issue=4 |pages=435–47 |year=1976 |month=December |pmid=1002868 |doi=10.1002/cne.901700404 |url=}}</ref>, which attracted more attention to the reeler mutation. |

||

In [[1995]], the RELN gene and protein were discovered at chromosome 7q22 by Gabriella D'Arcangelo and colleagues<ref name="Darcan1">D'Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T |

In [[1995]], the RELN gene and protein were discovered at chromosome 7q22 by Gabriella D'Arcangelo and colleagues<ref name="Darcan1">{{cite journal |author=D'Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T |title=A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler |journal=Nature |volume=374 |issue=6524 |pages=719–23 |year=1995 |month=April |pmid=7715726 |doi=10.1038/374719a0 |url=}}</ref>. Almost immediately, Japanese scientists at [[Kochi Medical School]] had successfully created the first [[Monoclonal antibodies|monoclonal antibody]] for reelin, called CR-50.<ref name="cr50">{{cite journal |author=Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K, ''et al'' |title=The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons |journal=Neuron |volume=14 |issue=5 |pages=899–912 |year=1995 |month=May |pmid=7748558 |doi= |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/0896-6273(95)90329-1}}</ref> They noted that CR-50 reacted specifically with [[Cajal-Retzius cell|Cajal-Retzius neurons]], whose functional role was unknown till then. |

||

The downstream pathway of Reelin was clarified using other mutant mice, including [[yotari]] and [[Scrambler mouse|scrambler]]. These mice have phenotypes similar to that of reeler but have no mutation in reelin. It was then demonstrated that the mouse ''disabled homologue 1'' ([[DAB1|Dab1]]) gene, which encodes a homolog of ''Drosophila disabled'', is the gene responsible for the phenotypes of these mutant mice, and Dab1 protein was absent (yotari) or only barely (scrambler) detectable in these mutants.<ref name="yotari_and_scrambler">Sheldon M, Rice DS, D'Arcangelo G, |

The downstream pathway of Reelin was clarified using other mutant mice, including [[yotari]] and [[Scrambler mouse|scrambler]]. These mice have phenotypes similar to that of reeler but have no mutation in reelin. It was then demonstrated that the mouse ''disabled homologue 1'' ([[DAB1|Dab1]]) gene, which encodes a homolog of ''Drosophila disabled'', is the gene responsible for the phenotypes of these mutant mice, and Dab1 protein was absent (yotari) or only barely (scrambler) detectable in these mutants.<ref name="yotari_and_scrambler">{{cite journal |author=Sheldon M, Rice DS, D'Arcangelo G, ''et al'' |title=Scrambler and yotari disrupt the disabled gene and produce a reeler-like phenotype in mice |journal=Nature |volume=389 |issue=6652 |pages=730–3 |year=1997 |month=October |pmid=9338784 |doi=10.1038/39601 |url=}}</ref> Targeted disruption of Dab1 also caused a phenotype similar to that of reeler. |

||

| Line 73: | Line 73: | ||

|} |

|} |

||

The Reelin receptors, apolipoprotein E receptor 2 and very-low-density lipoprotein receptor, were discovered serendipitously by Trommsdorff et al, who found that the double [[Gene knockout|knockout]] mice for apolipoprotein E receptor 2 and very-low-density lipoprotein receptor, which they generated for another experiment, showed defects in cortical layering similar to that in reeler.<ref name="receptors_discovery">Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T, |

The Reelin receptors, apolipoprotein E receptor 2 and very-low-density lipoprotein receptor, were discovered serendipitously by Trommsdorff et al, who found that the double [[Gene knockout|knockout]] mice for apolipoprotein E receptor 2 and very-low-density lipoprotein receptor, which they generated for another experiment, showed defects in cortical layering similar to that in reeler.<ref name="receptors_discovery">{{cite journal |author=Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T, ''et al'' |title=Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2 |journal=Cell |volume=97 |issue=6 |pages=689–701 |year=1999 |month=June |pmid=10380922 |doi= |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0092-8674(00)80782-5}}</ref> |

||

In the July of 2006, a group of Japanese scientists published the first report of [[X-ray crystallography]] and [[electron tomography]] investigation of reelin structure.<ref name="reelinstructure2006japan"/> |

In the July of 2006, a group of Japanese scientists published the first report of [[X-ray crystallography]] and [[electron tomography]] investigation of reelin structure.<ref name="reelinstructure2006japan"/> |

||

==Secretion and localization of reelin== |

==Secretion and localization of reelin== |

||

Studies show that Reelin is absent from [[synaptic vesicle]]s and is secreted via [[secretory pathway|constitutive secretory pathway]], being stored in [[Golgi apparatus|Golgi]] secretory vesicles.<ref name="golgi">Lacor PN, Grayson DR, Auta J, Sugaya I, Costa E, Guidotti A |

Studies show that Reelin is absent from [[synaptic vesicle]]s and is secreted via [[secretory pathway|constitutive secretory pathway]], being stored in [[Golgi apparatus|Golgi]] secretory vesicles.<ref name="golgi">{{cite journal |author=Lacor PN, Grayson DR, Auta J, Sugaya I, Costa E, Guidotti A |title=Reelin secretion from glutamatergic neurons in culture is independent from neurotransmitter regulation |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=97 |issue=7 |pages=3556–61 |year=2000 |month=March |pmid=10725375 |pmc=16278 |doi=10.1073/pnas.050589597 |url=http://www.pubmedcentral.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=10725375}}</ref> Reelin's release rate is not regulated by [[depolarization]], but strictly depends on its synthesis rate. This relationship is similar to that reported for the secretion of other [[Extracellular matrix|ECM]] proteins. |

||

In the cortex and hippocampus, reelin is secreted by [[Cajal-Retzius cell]]s, Cajal cells, and Retzius cells during brain development.<!-- |

In the cortex and hippocampus, reelin is secreted by [[Cajal-Retzius cell]]s, Cajal cells, and Retzius cells during brain development.<!-- |

||

--><ref name="cr_cells">Meyer G, Goffinet AM, |

--><ref name="cr_cells">{{cite journal |author=Meyer G, Goffinet AM, Fairén A |title=What is a Cajal-Retzius cell? A reassessment of a classical cell type based on recent observations in the developing neocortex |journal=Cereb. Cortex |volume=9 |issue=8 |pages=765–75 |year=1999 |month=December |pmid=10600995 |doi= |url=http://cercor.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10600995}}</ref><!-- |

||

--> In the cerebellum, Reelin is expressed first in the external [[granule cell]] layer (EGL) before the granule cell migration to the internal granule cell layer (IGL)<!-- |

--> In the cerebellum, Reelin is expressed first in the external [[granule cell]] layer (EGL) before the granule cell migration to the internal granule cell layer (IGL)<!-- |

||

--><ref> |

--><ref>{{cite journal |author=Schiffmann SN, Bernier B, Goffinet AM |title=Reelin mRNA expression during mouse brain development |journal=Eur. J. Neurosci. |volume=9 |issue=5 |pages=1055–71 |year=1997 |month=May |pmid=9182958 |doi= |url=}}</ref>.<!-- |

||

--> In the adult brain, Reelin is expressed by [[GABA]]-ergic [[interneuron]]s of the cortex and glutamatergic cerebellar neurons.<!-- |

--> In the adult brain, Reelin is expressed by [[GABA]]-ergic [[interneuron]]s of the cortex and glutamatergic cerebellar neurons.<!-- |

||

--><ref name="Interneurons">Pesold C, Impagnatiello F, Pisu MG, |

--><ref name="Interneurons">{{cite journal |author=Pesold C, Impagnatiello F, Pisu MG, ''et al'' |title=Reelin is preferentially expressed in neurons synthesizing gamma-aminobutyric acid in cortex and hippocampus of adult rats |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=95 |issue=6 |pages=3221–6 |year=1998 |month=March |pmid=9501244 |pmc=19723 |doi= |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9501244}}</ref><!-- |

||

--> Among GABAergic interneurons, Reelin seems to be detected predominantly in those expressing [[calretinin]] and [[calbindin]], like [[bitufted neuron|bitufted]], [[horizontal neuron|horizontal]], and [[Martinotti cell]]s, but not [[parvalbumin]]-expressing cells, like [[chandelier neuron|chandelier]] or [[basket neuron]]s.<!-- |

--> Among GABAergic interneurons, Reelin seems to be detected predominantly in those expressing [[calretinin]] and [[calbindin]], like [[bitufted neuron|bitufted]], [[horizontal neuron|horizontal]], and [[Martinotti cell]]s, but not [[parvalbumin]]-expressing cells, like [[chandelier neuron|chandelier]] or [[basket neuron]]s.<!-- |

||

--><ref name="Regional_patterns_1998"> |

--><ref name="Regional_patterns_1998">{{cite journal |author=Alcántara S, Ruiz M, D'Arcangelo G, ''et al'' |title=Regional and cellular patterns of reelin mRNA expression in the forebrain of the developing and adult mouse |journal=J. Neurosci. |volume=18 |issue=19 |pages=7779–99 |year=1998 |month=October |pmid=9742148 |doi= |url=http://www.jneurosci.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9742148}}</ref><!-- |

||

--><!-- |

--><!-- |

||

--><ref name="No_parvalbumin_1999">Pesold C, Liu WS, Guidotti A, Costa E, Caruncho HJ |

--><ref name="No_parvalbumin_1999">{{cite journal |author=Pesold C, Liu WS, Guidotti A, Costa E, Caruncho HJ |title=Cortical bitufted, horizontal, and Martinotti cells preferentially express and secrete reelin into perineuronal nets, nonsynaptically modulating gene expression |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=96 |issue=6 |pages=3217–22 |year=1999 |month=March |pmid=10077664 |pmc=15922 |doi= |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10077664}}</ref><!-- |

||

--> Outside the brain, reelin is found in adult mammalian blood, [[liver]], pituitary [[pars intermedia]], and adrenal [[chromaffin cell]]s. <!-- |

--> Outside the brain, reelin is found in adult mammalian blood, [[liver]], pituitary [[pars intermedia]], and adrenal [[chromaffin cell]]s. <!-- |

||

--><ref name="bodyexpr">Smalheiser NR, Costa E, Guidotti A, |

--><ref name="bodyexpr">{{cite journal |author=Smalheiser NR, Costa E, Guidotti A, ''et al'' |title=Expression of reelin in adult mammalian blood, liver, pituitary pars intermedia, and adrenal chromaffin cells |journal=Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. |volume=97 |issue=3 |pages=1281–6 |year=2000 |month=February |pmid=10655522 |pmc=15597 |doi= |url=http://www.pnas.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=10655522}}</ref><!-- |

||

--> In the liver, reelin is localized in [[hepatic stellate cell]]s.<ref name="liver2">Samama B, Boehm N |

--> In the liver, reelin is localized in [[hepatic stellate cell]]s.<ref name="liver2">{{cite journal |author=Samama B, Boehm N |title=Reelin immunoreactivity in lymphatics and liver during development and adult life |journal=Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol |volume=285 |issue=1 |pages=595–9 |year=2005 |month=July |pmid=15912522 |doi=10.1002/ar.a.20202 |url=http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/cgi-bin/fulltext/110501225/HTMLSTART}}</ref><!-- |

||

--> Its expression goes up when the liver is damaged, and returns to normal following its repair.<!-- |

--> Its expression goes up when the liver is damaged, and returns to normal following its repair.<!-- |

||

--> <ref name="Kobold_2002_liver1">Kobold D, Grundmann A, Piscaglia F, |

--> <ref name="Kobold_2002_liver1">{{cite journal |author=Kobold D, Grundmann A, Piscaglia F, ''et al'' |title=Expression of reelin in hepatic stellate cells and during hepatic tissue repair: a novel marker for the differentiation of HSC from other liver myofibroblasts |journal=J. Hepatol. |volume=36 |issue=5 |pages=607–13 |year=2002 |month=May |pmid=11983443 |doi= |url=http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0168827802000508}}</ref> |

||

[[image:Schema of the Reelin protein vertical en.png|thumb|right|Schema of the Reelin protein]] |

[[image:Schema of the Reelin protein vertical en.png|thumb|right|Schema of the Reelin protein]] |

||

Revision as of 12:56, 7 July 2008

| RELN | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | RELN, LIS2, PRO1598, RL, reelin, ETL7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 600514; MGI: 103022; HomoloGene: 3699; GeneCards: RELN; OMA:RELN - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Reelin is a protein found mainly in the brain, but also in the spinal cord, blood and other body organs and tissues. Reelin is crucial for regulating the processes of neuronal migration and positioning in the developing brain. Besides this important role in the early period, reelin continues to work in the adult brain. It modulates the synaptic plasticity by enhancing LTP induction and maintenance.[5][6] It also stimulates dendrite development[7] and regulates the continuing migration of neuroblasts generated in adult neurogenesis sites like subventricular and subgranular zones.

Reelin is implicated in pathogenesis of several brain diseases: significantly lowered expression of the protein have been found in schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder. Total lack of reelin causes a form of lissencephaly; reelin also may play a role in Alzheimer's disease, temporal lobe epilepsy, and autism.

Reelin's name comes from the abnormal reeling gait of reeler mice,[8] which were found to have a deficiency of this brain protein and were homozygous for the RELN gene, which encodes reelin synthesis. The primary phenotype associated with loss of reelin function is inverted cortex, a neuroanatomical defect in which the six cortical layers are inverted. Heterozygous mice for the reelin gene have very little obvious neuroanatomical defect but those that they have resemble the changes of the human schizophrenic brain.

History

Mutant mice provide insight into the underlying molecular mechanisms of the development of the CNS. These spontaneous mutations were first identified by scientists interested in motor behavior, and it proved relatively easy to screen littermates for mice that showed difficulties moving around the cage. A number of such mice were found and given descriptive names such as reeler, weaver, lurcher, nervous, and staggerer.

The "reeler" mouse was first described in the 1951 edition of Journal of Genetics by Douglas Scott Falconer.[8] Histopathological studies in the 1960's revealed that the reeler cerebellum is dramatically decreased in size and the normal laminar organization found in several brain regions is disrupted.[9] 1970's brought the discovery of cellular layers inversion in the mice neocortex[10], which attracted more attention to the reeler mutation.

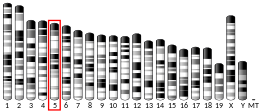

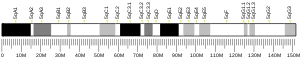

In 1995, the RELN gene and protein were discovered at chromosome 7q22 by Gabriella D'Arcangelo and colleagues[11]. Almost immediately, Japanese scientists at Kochi Medical School had successfully created the first monoclonal antibody for reelin, called CR-50.[12] They noted that CR-50 reacted specifically with Cajal-Retzius neurons, whose functional role was unknown till then.

The downstream pathway of Reelin was clarified using other mutant mice, including yotari and scrambler. These mice have phenotypes similar to that of reeler but have no mutation in reelin. It was then demonstrated that the mouse disabled homologue 1 (Dab1) gene, which encodes a homolog of Drosophila disabled, is the gene responsible for the phenotypes of these mutant mice, and Dab1 protein was absent (yotari) or only barely (scrambler) detectable in these mutants.[13] Targeted disruption of Dab1 also caused a phenotype similar to that of reeler.

|

|

The Reelin receptors, apolipoprotein E receptor 2 and very-low-density lipoprotein receptor, were discovered serendipitously by Trommsdorff et al, who found that the double knockout mice for apolipoprotein E receptor 2 and very-low-density lipoprotein receptor, which they generated for another experiment, showed defects in cortical layering similar to that in reeler.[14]

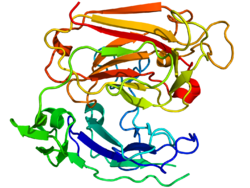

In the July of 2006, a group of Japanese scientists published the first report of X-ray crystallography and electron tomography investigation of reelin structure.[15]

Secretion and localization of reelin

Studies show that Reelin is absent from synaptic vesicles and is secreted via constitutive secretory pathway, being stored in Golgi secretory vesicles.[16] Reelin's release rate is not regulated by depolarization, but strictly depends on its synthesis rate. This relationship is similar to that reported for the secretion of other ECM proteins.

In the cortex and hippocampus, reelin is secreted by Cajal-Retzius cells, Cajal cells, and Retzius cells during brain development.[17] In the cerebellum, Reelin is expressed first in the external granule cell layer (EGL) before the granule cell migration to the internal granule cell layer (IGL)[18]. In the adult brain, Reelin is expressed by GABA-ergic interneurons of the cortex and glutamatergic cerebellar neurons.[19] Among GABAergic interneurons, Reelin seems to be detected predominantly in those expressing calretinin and calbindin, like bitufted, horizontal, and Martinotti cells, but not parvalbumin-expressing cells, like chandelier or basket neurons.[20][21] Outside the brain, reelin is found in adult mammalian blood, liver, pituitary pars intermedia, and adrenal chromaffin cells. [22] In the liver, reelin is localized in hepatic stellate cells.[23] Its expression goes up when the liver is damaged, and returns to normal following its repair. [24]

Structure

Reelin is a secreted extracellular matrix glycoprotein composed of 3461 amino acids with a relative molecular mass of 388 kDa.

Reelin molecule starts with a signaling peptide 27 amino acids in length, followed by a region bearing similarity to F-spondin, marked as "SP" on the scheme, and by a region unique to reelin, marked as "H". Next come the 8 repeats of 300-350 amino acids. These are called reelin repeats and have an EGF motif at their center, dividing each repeat into two subrepeats, A and B. Despite this interruption, the two subdomains make direct contact, resulting in a compact overall structure.[15]

The last comes a highly basic and short C-terminal region (CTR, marked "+") with a length of 32 amino acids. This region is extremely conservative, being 100% identical in all investigated mammals. It was thought that CTR is necessary for reelin secretion, because Orleans reeler mutation, which lacks a part of 8th repeat and the whole CTR, is unable to secrete the misshaped protein, leading to its concentration in cytoplasm. However, one recent study has shown that the CTR is not essential for secretion, which is most probably hindered then reelin is cut along one of the repeats.[25]

Reelin is cleaved in vivo at two sites located after domains 2 and 6 - approximately between repeats 2 and 3 and between repeats 6 and 7, resulting in the production of three fragments.[26] This splitting does not decrease the protein's activity, as constructs made of the predicted central fragments (repeats 3–6) bind to lipoprotein receptors, trigger Dab1 phosphorylation and mimic functions of reelin during cortical plate development.[27]

Function and mechanism of action

In the process of neural development, Reelin acts on migrating neuronal precursors and controls correct cell positioning in the cortex and other brain structures. The proposed role is one of a dissociation signal for neuronal groups, allowing them to separate and go from tangential chain-migration to radial individual migration.[28] Dissociation detaches migrating neurons from the glial cells that are acting as their guides, converting them into individual cells that can strike out alone to find their final position.

In the adult brain, Reelin plays an important role by modulating cortical pyramidal neuron dendritic spine expression density, the branching of dendrites, and the expression of long-term potentiation.

Mechanism of action

Reelin acts on two receptors:

which are members of the Low density lipoprotein receptor gene family.

The intracellular adaptor DAB1 binds to the VLDLR and ApoER2 through an NPxY motif and is involved in transmission of Reelin signals through these lipoprotein receptors.

The proposal that the protocadherin CNR1 behaves as a Reelin receptor[29] has been disproved.[27]

It has been shown that alpha-3-beta-1 integrin binds to the N-terminal region of reelin, a site distinct from the region of reelin shown to associate with other reelin receptors such as VLDLR/ApoER2.[30]

Reelin molecules have been shown[31] [32] to form a large protein complex, a disulfide-linked homodimer. If the homodimer fails to form, efficient tyrosine phosphorylation of DAB1 also fails.

Reelin-dependent strengthening of long-term potentiation is caused by ApoER2 interaction with NMDA receptor. This interaction happens when ApoER2 has a region coded by exon 19. ApoER2 gene is alternatively spliced, with the exon 19-containing variant more actively produced during periods of activity.[33]

Role in brain pathology

Lissencephaly

Disruptions of the RELN gene are condsidered to be the cause of the rare form of lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia called Norman-Roberts syndrome.[34][35] The mutations disrupt splicing of RELN cDNA, resulting in low or undetectable amounts of reelin protein. The phenotype in these patients was characterized by hypotonia, ataxia, and developmental delay, with lack of unsupported sitting and profound mental retardation with little or no language development. Seizures and congenital lymphedema were also present.

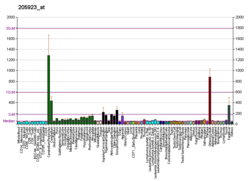

Reduced expression of reelin and its mRNA levels in the brains of schizophrenia sufferers had been reported in 1998[36] and 2000[37] and independently confirmed in the postmortem studies of hippocampus samples[38] and in the cortex studies.[39][40] The reduction may reach up to 50% in some brain regions and is coupled with reduced expression of GAD-67 enzyme,[41] which catalyses the transition of glutamate to GABA. Blood levels of reelin and its isoforms are also altered in schizophrenia, along with other mood disorders, according to one study.[42] Reduced reelin mRNA prefrontal expression in schizophrenia was found to be the most statistically relevant disturbance found in the multicenter study conducted in 14 separate laboratories in 2001 by Stanley Foundation Neuropathology Consortium.[43]

Epigenetic hypermethylation of DNA in schizophrenia patients is proposed as a cause of the reduction,[44][45] in accordance with the knowledge that administration of methionine to schizophrenic patients results in a profound exacerbation of schizophrenia symptoms in sixty to seventy percent of patients, a fact discovered in the 1960's.[46][47][48][49] In contrast with initial data, subsequent studies failed to confirm the hypermethylation.[50][51] A postmortem study comparing DNMT1 and Reelin mRNA expression in cortical layers I and V of schizophrenic patients and normal controls demonstrated that in the layer V both DNMT1 and Reelin levels were normal, while in the layer I DNMT1 was threefold higher, probably leading to the twofold decrease in the Reelin expression. [52] Methylation inhibitors and histone deacetylase inhibitors, such as valproic acid, increase reelin mRNA levels,[53] [54] [55] while L-methionine treatment downregulates the phenotypic expression of reelin. [56]

Heterozygous reeler mouse, which is haploinsufficient for the reeler gene, shares several neurochemical and behavioral abnormalities with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder[57], but considered as not suitable for use as a genetic mouse model of schizophrenia.[58]

Bipolar disorder

Decrease in RELN expression is typical of bipolar disorder with psychosis, but is not characteristic of patients with major depression without psychosis.[37]

A number of studies have shown an association between the reelin gene and autism[59] [60]. A couple of studies were unable to duplicate linkage findings, however.[61][62]

Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Decreased reelin expression in the hippocampal tissue samples from patients with temporal lobe epilepsy was found to be directly correlated to the extent of granule cell dispersion, a major feature of the disease.[63] [64] According to one study, prolonged seizures in a rat model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy have led to the loss of reelin-expressing interneurons and subsequent ectopic chain migration and aberrant integration of newborn dentate granule cells. Without reelin, the chain-migrating neuroblasts failed to detach properly.[65]

According to one study, reelin expression and glycosylation patterns are altered in Alzheimer's disease. In the cortex of the patients, reelin levels were 40% higher compared with controls, but the cerebellar levels of the protein remain normal in the same patients.[66] This finding correlates with an earlier study showing the presence of Reelin associated with amyloid plaques in a transgenic AD mouse model. [67]

Recommended reading

- Forster E, Jossin Y, Zhao S, Chai X, Frotscher M, Goffinet AM. (2006) Recent progress in understanding the role of Reelin in radial neuronal migration, with specific emphasis on the dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci. 23(4):901-9. Review. PMID 16519655 (free full text)

External links

Articles, publications, webpages

- The real role of reelin - publication in The Journal of Cell Biology, 2002

- Pleiotropic Action of Reelin in Psychosis - Web-lecture by Erminio Costa, MD., linking the reelin disfunction to schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

- Gabriella D'Arcangelo - the scientist who discovered the reelin gene and protein.

- Neuronal Migration in Cortical Development - article from the Medscape website. By Shigeaki Kanatani, MIS; Hidenori Tabata, PhD; Kazunori Nakajima MD, PhD. (2005) J Child Neurol. 20(4):274-279

- A short biography of the scientist who discovered the reeler mouse mutation - Mackay TF (2004) Douglas Scott Falconer (1913-2004). Heredity. 93(2):119-21. PMID 15241449

Figures and images

- Schematic representation of signaling through the LDLR family members apoER2 and VLDL receptor - figure from an article.

- Proposed mechanism by which mouse RELN promoter hypermethylation and recruitment of chromatin remodeling complexes (MeCP2, HDACs, and corepressors) regulate reelin gene expression - a figure from scientific publication by Dong et al.[45]

- Figure from an article. Corticogenesis in wild-type, reeler mutant and β1 deficient mice. - a pictorial rendition of the difference that the lack of reelin brings to the cortical structure.

- Reelin gene expression in mice - images from BGEM (Brain Gene Expression Map) site.

- Effects of human and naturally occurring mouse RELN mutations on the predicted protein - figure from an article by Susan E. Hong et al.[34]

- MRI analysis of chromosome 7q22-linked lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia - Brain images from the same article.[34]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000189056 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000042453 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Weeber EJ, Beffert U, Jones C; et al. (2002). "Reelin and ApoE receptors cooperate to enhance hippocampal synaptic plasticity and learning". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (42): 39944–52. doi:10.1074/jbc.M205147200. PMID 12167620.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link)W - ^ D'Arcangelo G (2005). "Apoer2: a reelin receptor to remember". Neuron. 47 (4): 471–3. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.001. PMID 16102527.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Niu S, Renfro A, Quattrocchi CC, Sheldon M, D'Arcangelo G (2004). "Reelin promotes hippocampal dendrite development through the VLDLR/ApoER2-Dab1 pathway". Neuron. 41 (1): 71–84. PMID 14715136.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Falconer DS (1951) 2 new mutants, trembler and reeler, with neurological actions in the house mouse (mus-musculus l) Journal of Genetics 50 (2): 192-201 [1]

- ^ Hamburgh M (1963). "Analysis of the postnatal developmental effects of "reeler", a neurological mutation in mice. A study in developmental genetics". Dev. Biol. 19: 165–85. PMID 14069672.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Caviness VS (1976). "Patterns of cell and fiber distribution in the neocortex of the reeler mutant mouse". J. Comp. Neurol. 170 (4): 435–47. doi:10.1002/cne.901700404. PMID 1002868.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ D'Arcangelo G, Miao GG, Chen SC, Soares HD, Morgan JI, Curran T (1995). "A protein related to extracellular matrix proteins deleted in the mouse mutant reeler". Nature. 374 (6524): 719–23. doi:10.1038/374719a0. PMID 7715726.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ogawa M, Miyata T, Nakajima K; et al. (1995). "The reeler gene-associated antigen on Cajal-Retzius neurons is a crucial molecule for laminar organization of cortical neurons". Neuron. 14 (5): 899–912. PMID 7748558.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Sheldon M, Rice DS, D'Arcangelo G; et al. (1997). "Scrambler and yotari disrupt the disabled gene and produce a reeler-like phenotype in mice". Nature. 389 (6652): 730–3. doi:10.1038/39601. PMID 9338784.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Trommsdorff M, Gotthardt M, Hiesberger T; et al. (1999). "Reeler/Disabled-like disruption of neuronal migration in knockout mice lacking the VLDL receptor and ApoE receptor 2". Cell. 97 (6): 689–701. PMID 10380922.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Nogi T, Yasui N, Hattori M, Iwasaki K, Takagi J. (2006) Structure of a signaling-competent reelin fragment revealed by X-ray crystallography and electron tomography. EMBO Journal. PMID 16858396

- ^ Lacor PN, Grayson DR, Auta J, Sugaya I, Costa E, Guidotti A (2000). "Reelin secretion from glutamatergic neurons in culture is independent from neurotransmitter regulation". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (7): 3556–61. doi:10.1073/pnas.050589597. PMC 16278. PMID 10725375.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Meyer G, Goffinet AM, Fairén A (1999). "What is a Cajal-Retzius cell? A reassessment of a classical cell type based on recent observations in the developing neocortex". Cereb. Cortex. 9 (8): 765–75. PMID 10600995.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Schiffmann SN, Bernier B, Goffinet AM (1997). "Reelin mRNA expression during mouse brain development". Eur. J. Neurosci. 9 (5): 1055–71. PMID 9182958.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pesold C, Impagnatiello F, Pisu MG; et al. (1998). "Reelin is preferentially expressed in neurons synthesizing gamma-aminobutyric acid in cortex and hippocampus of adult rats". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 (6): 3221–6. PMC 19723. PMID 9501244.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Alcántara S, Ruiz M, D'Arcangelo G; et al. (1998). "Regional and cellular patterns of reelin mRNA expression in the forebrain of the developing and adult mouse". J. Neurosci. 18 (19): 7779–99. PMID 9742148.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pesold C, Liu WS, Guidotti A, Costa E, Caruncho HJ (1999). "Cortical bitufted, horizontal, and Martinotti cells preferentially express and secrete reelin into perineuronal nets, nonsynaptically modulating gene expression". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96 (6): 3217–22. PMC 15922. PMID 10077664.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Smalheiser NR, Costa E, Guidotti A; et al. (2000). "Expression of reelin in adult mammalian blood, liver, pituitary pars intermedia, and adrenal chromaffin cells". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97 (3): 1281–6. PMC 15597. PMID 10655522.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Samama B, Boehm N (2005). "Reelin immunoreactivity in lymphatics and liver during development and adult life". Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 285 (1): 595–9. doi:10.1002/ar.a.20202. PMID 15912522.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help) - ^ Kobold D, Grundmann A, Piscaglia F; et al. (2002). "Expression of reelin in hepatic stellate cells and during hepatic tissue repair: a novel marker for the differentiation of HSC from other liver myofibroblasts". J. Hepatol. 36 (5): 607–13. PMID 11983443.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nakano Y, Kohno T, Hibi T, Kohno S, Baba A, Mikoshiba K, Nakajima K, Hattori M. (2007) The extremely conserved C-terminal region of reelin is not necessary for secretion but is required for efficient activation of downstream signaling. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007 May 15; PMID 17504759 free full text

- ^ Lambert de Rouvroit C, de Bergeyck V, Cortvrindt C, Bar I, Eeckhout Y, Goffinet AM.(1999) Reelin, the extracellular matrix protein deficient in reeler mutant mice, is processed by a metalloproteinase. Exp Neurol. 156(1):214-7. PMID 10192793

- ^ a b Jossin, Y., Ignatova, N., Hiesberger, T., Herz, J., Lambert de Rouvroit, C. & Goffinet, A.M. (2004) The central fragment of Reelin, generated by proteolytic processing in vivo, is critical to its function during cortical plate development. J. Neurosci., 24, 514–521. PMID 14724251 (free full text)

- ^ Hack I, Bancila M, Loulier K, Carroll P, Cremer H. (2002) Reelin is a detachment signal in tangential chain-migration during postnatal neurogenesis. Nature Neuroscience 5(10):939-45. PMID 12244323

- ^ Senzaki K, Ogawa M, Yagi T. (1999) Proteins of the CNR family are multiple receptors for Reelin. Cell. 99(6):635-47. PMID 10612399

- ^ Schmid RS, Jo R, Shelton S, Kreidberg JA, Anton ES. (2005) Reelin, integrin and DAB1 interactions during embryonic cerebral cortical development. Cereb Cortex 15(10):1632-6. PMID 15703255

- ^ Utsunomiya-Tate N, Kubo K, Tate S, Kainosho M, Katayama E, Nakajima K, Mikoshiba K. (2000) Reelin molecules assemble together to form a large protein complex, which is inhibited by the function-blocking CR-50 antibody. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000 Aug 15;97(17):9729 PMID 10920200 free full text

- ^ Kubo K, Mikoshiba K, Nakajima K. (2002) Neurosci Res. 43(4):381-8. Secreted Reelin molecules form homodimers. PMID 12135781

- ^ Beffert U, Weeber EJ, Durudas A, Qiu S, Masiulis I, Sweatt JD, Li WP, Adelmann G, Frotscher M, Hammer RE, Herz J. Modulation of synaptic plasticity and memory by Reelin involves differential splicing of the lipoprotein receptor Apoer2. Neuron . 2005 Aug 18 ; 47(4):567-79. PMID 16102539 free full text PDF

- ^ a b c Hong SE, Shugart YY, Huang DT, Shahwan SA, Grant PE, Hourihane JO, Martin ND, Walsh CA. (2000) Nat Genet. 26(1):93-6. Autosomal recessive lissencephaly with cerebellar hypoplasia is associated with human RELN mutations. PMID 10973257

- ^ Crino P. (2001) New RELN Mutation Associated with Lissencephaly and Epilepsy. Epilepsy Curr. 2001 Nov;1(2):72. PMID 15309195

- ^ Francesco Impagnatiello, Alessandro R. Guidotti, Christine Pesold, Yogesh Dwivedi, Hector Caruncho, Maria G. Pisu, Doncho P. Uzunov, Neil R. Smalheiser, John M. Davis, Ghanshyam N. Pandey, George D. Pappas, Patricia Tueting, Rajiv P. Sharma, and Erminio Costa (1998) A decrease of reelin expression as a putative vulnerability factor in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998 December 22; 95(26): 15718–15723. PMID 9861036

- ^ a b Guidotti, A., Auta, J., Davis, J. M., DiGiorgi-Gerenini, V., Dwivedi, J., Grayson, D. R., Impagnatiello, F., Pandey, G. N., Pesold, C., Sharma, R. F., et al. (2000) Decrease in reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 (GAD67) expression in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a postmortem brain study.Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 57, 1061-1069. PMID 11074872

- ^ Fatemi, S. H., Earle, J. A. & McMenomy, T. (2000) Reduction in Reelin immunoreactivity in hippocampus of subjects with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression. Mol. Psych. 5, 654-663. PMID 11126396

- ^ Eastwood, S. L. & Harrison, P. J. (2003) Interstitial white matter neurons express less reelin and are abnormally distributed in schizophrenia: towards an integration of molecular and morphologic aspects of the neurodevelopmental hypothesis. Mol. Psychiatry 8, 821-831. PMID 12931209

- ^ Abdolmaleky, H. M., Cheng, H.-H., Russo, A., Smith, C. L., Faraone, S. V., Wilcox, M., Shafa, R., Glatt, S. J., Nguyen, G., Ponte, J. F., et al. (2005) Hypermethylation of the reelin (RELN) promoter in the brain of schizophrenic patients: a preliminary report. Am. J. Med. Genet. B 134, 60-66. PMID 15717292

- ^ Fatemi SH, Stary JM, Earle JA, Araghi-Niknam M, Eagan E. GABAergic dysfunction in schizophrenia and mood disorders reflected by decreased levels of glutamic acid decarboxylase and 67 kDa and reelin proteins in cerebellum. Schizophr Res 2005;72:109-122. PMID 15560956

- ^ Fatemi SH, Kroll JL, Stary JM. (2001) Altered levels of Reelin and its isoforms in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Neuroreport. 12(15):3209-15. PMID 11711858

- ^ Knable MB, Torrey EF, Webster MJ, Bartko JJ. (2001) Multivariate analysis of prefrontal cortical data from the Stanley Foundation Neuropathology Consortium. Brain Res Bull. 2001 Jul 15;55(5):651-9. PMID 11576762

- ^ Dennis R. Grayson, Xiaomei Jia, Ying Chen, Rajiv P. Sharma, Colin P. Mitchell, Alessandro Guidotti, and Erminio Costa (2005) Reelin promoter hypermethylation in schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 June 28; 102(26): 9341–9346. PMID 15961543

- ^ a b Dong E, Agis-Balboa RC, Simonini MV, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A. (2005) Reelin and glutamic acid decarboxylase67 promoter remodeling in an epigenetic methionine-induced mouse model of schizophrenia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102(35):12578-83 PMID 16113080

- ^ Pollin, W., Cardon, P.V., and Kety, S.S. (1961) Effects of amino acid feedings in schizophrenia patients treated with iproniazid. Science 133 , 104–105.

- ^ Brune, G.G. and Himwich, H.E. (1962). Effects of methionine loading on the behavior of schizophrenia patients. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 134 , 447–450 PMID 13873983

- ^ Park, L., Baldessarini, R.J., and Kety, S.S. (1965). Effects of methionine ingestion in chronic schizophrenia patients treated with monoamine oxidase inhibitors. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 12 , 346–351 PMID 14258360

- ^ Antun, F.T., Burnett, G.B., Cooper, A.J., Daly, R.J., Smythies, J.R., and Zealley, A.K. (1971). The effects of L-methionine (without MAOI) in schizophrenia. J. Psychiatry Res. 8 , 63–71 PMID 4932991

- ^ Tochigi M, Iwamoto K, Bundo M, Komori A, Sasaki T, Kato N, Kato T (2007). "Methylation Status of the Reelin Promoter Region in the Brain of Schizophrenic Patients". Biological Psychiatry. 63: 530. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.07.003. PMID 17870056.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mill J, Tang T, Kaminsky Z, Khare T, Yazdanpanah S, Bouchard L, Jia P, Assadzadeh A, Flanagan J, Schumacher A, Wang SC, Petronis A (2008). "Epigenomic profiling reveals DNA-methylation changes associated with major psychosis". Am. J. Hum. Genet. 82 (3): 696–711. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.008. PMID 18319075.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Ruzicka WB, Zhubi A, Veldic M, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A. (2007) Selective epigenetic alteration of layer I GABAergic neurons isolated from prefrontal cortex of schizophrenia patients using laser-assisted microdissection. Mol Psychiatry. PMID 17264840 doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001954.

- ^ Tremolizzo L, Doueiri MS, Dong E, Grayson DR, Davis J, Pinna G, Tueting P, Rodriguez-Menendez V, Costa E, Guidotti A. (2005) Valproate corrects the schizophrenia-like epigenetic behavioral modifications induced by methionine in mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 Mar 1;57(5):500-9. PMID 15737665

- ^ Chen. Y., Sharma, R., Costa, R. H., Costa, E. & Grayson, D. R. (2002) On the epigenetic regulation of the human reelin promoter. Nucl. Acids Res. 3, 2930-2939. PMID 12087179

- ^ Colin P. Mitchell, Ying Chen, Marija Kundakovic, Erminio Costa and Dennis R. Grayson (2005) Histone deacetylase inhibitors decrease reelin promoter methylation in vitro J Neurochem. 2005 Apr;93(2):483-92. PMID 15816871

- ^ Tremolizzo L, Carboni G, Ruzicka WB, Mitchell CP, Sugaya I, Tueting P, Sharma R, Grayson DR, Costa E, Guidotti A. (2002) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99(26):17095-100. An epigenetic mouse model for molecular and behavioral neuropathologies related to schizophrenia vulnerability. PMID 12481028

- ^ Podhorna J, Didriksen M. (2004) The heterozygous reeler mouse: behavioural phenotype. Behav Brain Res. 153(1):43-54. PMID 15219705

- ^ Serajee FJ, Zhong H, Mahbubul Huq AH.(2006) Association of Reelin gene polymorphisms with autism. Genomics. 2006 Jan;87(1):75-83. Epub 2005 Nov 28. PMID 16311013

- ^ Skaar DA, Shao Y, Haines JL, Stenger JE, Jaworski J, Martin ER, DeLong GR, Moore JH, McCauley JL, Sutcliffe JS, Ashley-Koch AE, Cuccaro ML, Folstein SE, Gilbert JR, Pericak-Vance MA. (2005) Analysis of the RELN gene as a genetic risk factor for autism. Mol Psychiatry. 2005 Jun;10(6):563-71. PMID 15558079

- ^ Devlin B, Bennett P, Dawson G, Figlewicz DA, Grigorenko EL, McMahon W, Minshew N, Pauls D, Smith M, Spence MA, Rodier PM, Stodgell C, Schellenberg GD; CPEA Genetics Network. (2004) Alleles of a reelin CGG repeat do not convey liability to autism in a sample from the CPEA network. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004 Apr 1;126(1):46-50. PMID 15048647

- ^ Li J, Nguyen L, Gleason C, Lotspeich L, Spiker D, Risch N, Myers RM.(2004) Lack of evidence for an association between WNT2 and RELN polymorphisms and autism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2004 Apr 1;126(1):51-7. PMID 15048648

- ^ Carola A. Haas, Oliver Dudeck, Matthias Kirsch, Csaba Huszka, Gunda Kann, Stefan Pollak, Josef Zentner, and Michael Frotscher (2002) Role for reelin in the development of granule cell dispersion in temporal lobe epilepsy. The Journal of Neuroscience, 22(14):5797-5802 PMID 12122039

- ^ Heinrich C, Nitta N, Flubacher A, Muller M, Fahrner A, Kirsch M, Freiman T, Suzuki F, Depaulis A, Frotscher M, Haas CA. (2006) Reelin deficiency and displacement of mature neurons, but not neurogenesis, underlie the formation of granule cell dispersion in the epileptic hippocampus. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(17):4701-4713 PMID 16641251

- ^ Gong C, Wang TW, Huang HS, Parent JM. (2007) Reelin regulates neuronal progenitor migration in intact and epileptic hippocampus. J Neurosci. 27(8):1803-11. PMID 17314278

- ^ Botella-Lopez A, Burgaya F, Gavin R, Garcia-Ayllon MS, Gomez-Tortosa E, Pena-Casanova J, Urena JM, Del Rio JA, Blesa R, Soriano E, Saez-Valero J. (2006) Reelin expression and glycosylation patterns are altered in Alzheimer's disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 103(14):5573-8. PMID 16567613

- ^ Wirths O, Multhaup G, Czech C, Blanchard V, Tremp G, Pradier L, Beyreuther K, Bayer TA. (2001) Reelin in plaques of beta-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin-1 double-transgenic mice. Neurosci Lett. 316(3):145-8. PMID 11744223