Spanish cruiser Cristóbal Colón

Cristóbal Colón in 1897–1898 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Giuseppe Garibaldi |

| Namesake | Giuseppe Garibaldi |

| Builder | Italy |

| Laid down | 1895 |

| Launched | September 1896 |

| Fate | Sold to Spain, 16 May 1897 |

| Name | Cristóbal Colón |

| Namesake | Christopher Columbus |

| Completed | May 1897 |

| Acquired | 16 May 1897 |

| Fate | Sunk 3 July 1898 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type | Giuseppe Garibaldi-class armored cruiser |

| Displacement | 6,840 long tons (6,950 t) normal (7,972 long tons (8,100 t) full load) |

| Length | 366 ft 8 in (111.76 m) |

| Beam | 59 ft 10+1⁄2 in (18.250 m) |

| Draft | 23 ft 3+1⁄2 in (7.099 m) maximum |

| Installed power | 13,655–14,713 ihp (10.183–10.971 MW) |

| Propulsion | Vertical triple expansion, 24 boilers |

| Speed | 19.3–20.02 knots (35.74–37.08 km/h) |

| Range | 4,400 nmi (8,100 km) at 10 kn (19 km/h) |

| Endurance | 1,050 long tons (1,070 t) coal (normal) |

| Complement | 510 to 559 officers and enlisted |

| Armament |

|

| Armor |

|

Cristóbal Colón was a Giuseppe Garibaldi-class armored cruiser of the Spanish Navy that fought at the Battle of Santiago de Cuba during the Spanish–American War.

Technical characteristics

Cristóbal Colón was built in Italy under the name Giuseppe Garibaldi, being the second ship of the class to be laid down with that name. She was laid down in 1895, launched in September 1896, sold to Spain, and delivered to the Spanish Navy at Genoa on 16 May 1897.[1] She had two funnels and was fast, well armed, and well protected, especially for her displacement. She was designed to be an intermediate type of ship between extant battleships and cruisers, powerful enough to function as a part of a battle fleet and yet fast enough to outrun more powerful ships, and in this sense was the Spanish Navy's first true armored cruiser. However, the Spanish Ministry of Marine rejected her 10-inch (250 mm) guns, and she was delivered without them, detracting considerably from her designed firepower; she was lost before the guns could be installed.[2]

Operational history

Cristóbal Colón was part of the Spanish Navy's 1st Squadron when tensions with the United States were rising after the explosion and sinking of the battleship USS Maine in the harbor at Havana, Cuba on 15 February 1898. The squadron concentrated at São Vicente in Portugal's Cape Verde Islands; departing Cadiz on 8 April. The Spanish–American War began while Cristóbal Colón was at São Vicente. Ordered by neutral Portugal in accordance with international law to leave São Vicente within 24 hours of the declaration of war, Cristóbal Colón and the rest of Cervera's squadron departed on 29 April 1898, bound for San Juan, Puerto Rico. Cervera's ships reached French-owned Martinique in the Lesser Antilles on 10 May 1898. While Cristóbal Colón and the other large ships loitered in international waters, two Spanish destroyers went into Fort-de-France to ask for coal. France was neutral and would not supply coal, so the Spanish squadron departed on 12 May 1898 for Dutch-owned Curaçao, where Cervera expected to meet a collier. Cervera arrived at Willemstad on 14 May 1898, but the Netherlands was also neutral, and strictly enforced its neutrality by allowing only Infanta Maria Teresa and her sister ship Vizcaya to enter port and permitting them to load only 600 long tons (610 t) of coal. On 15 May, Cervera's ships departed, no longer bound for San Juan, which by now was under a U.S. Navy blockade, but for as-yet unblockaded Santiago de Cuba on the southeastern coast of Cuba, arriving there on 19 May 1898. Cervera hoped to refit his ships there before he could be trapped. His squadron was still in the harbor of Santiago de Cuba when an American squadron arrived on 27 May 1898 and began a blockade which would drag on for 37 days.

Cristóbal Colón was anchored in the entrance channel to the harbor in a position where she could support the harbor's shore batteries, and on 28 May of 1898 was the first unit of Cervera's squadron the American blockaders identified as being at Santiago de Cuba. The first American offensive action of the blockade was to attack her. At 1400 hours on 31 May 1898, the battleships USS Iowa and USS Massachusetts and cruiser USS New Orleans opened fire on Cristóbal Colón and the shore fortifications at the then-great range of 7,000 yards (6,400 m), and Cristóbal Colón and the coastal artillery returned fire. The Americans ceased fire at 1410, and the Spanish at 1500. Neither side suffered any casualties.

The blockade wore on, with Cristóbal Colón and the others enduring occasional American naval bombardments of the harbor. Some of her men joined others from the fleet in a Naval Brigade to fight against a U.S. Army overland drive toward Santiago de Cuba.

By the beginning of July 1898, that drive threatened to capture Santiago de Cuba, and Cervera decided that his squadron's only hope was to try to escape into the open sea by running the blockade. The decision was made on 1 July 1898, with the break-out set for 3 July 1898. The crew of Cristóbal Colón spent 2 July 1898 returning from Naval Brigade service and preparing for action. With Vice Admiral Cervera aboard, Infanta María Teresa was to lead the escape, sacrificing herself by attacking the fastest American ship, armored cruiser USS Brooklyn, allowing the rest of the squadron to avoid action and run westward for the open sea.

At about 0845 hours on 3 July 1898, the Spanish ships got underway and moved out in line-ahead formation, with Cristóbal Colón third in line, following Infanta María Teresa and armored cruiser Vizcaya; armored cruiser Almirante Oquendo and destroyers Furor and Plutón came along behind Cristóbal Colón. The U.S. squadron sighted the Spanish ships in the channel at about 0935, and the Battle of Santiago de Cuba began.

While Infanta María Teresa and Vizcaya charged Brooklyn, Cristóbal Colón, Almirante Oquendo, and the two destroyers turned west and worked up steam to make a run for the open sea. When Brooklyn turned eastward and away from Infanta María Teresa, all four Spanish armored cruisers wound up in the same line-ahead formation they had formed when leaving the harbor, brushing past the last obstacle in their path, the armed yacht USS Vixen.

The action now developed into a hot stern chase, with the U.S. squadron about a mile to port of the Spanish ships and slightly behind them, every ship on both sides firing with every gun she could bring to bear. Cristóbal Colón hit Iowa twice, wrecking her dispensary with the first hit and holing her below the waterline with the second, slowing Iowa but not forcing her to cease fire.

The outgunned Spanish squadron began to take losses, its ships catching fire and grounding themselves before their magazines could explode. Infanta María Teresa was first, shearing out of line and beaching herself at about 1025 a few miles west of Santiago de Cuba; Almirante Oquendo ran up on the beach a few hundred yards farther west five minutes later. At 1106, Vizcaya turned hard to starboard and ran herself ashore.

With the two Spanish destroyers by now also sunk, Cristóbal Colón steamed on alone, the last survivor of Cervera's squadron. For a time, it seemed that she might get away. Although her machinery was not able to get her up to her top speed after months of hard steaming, she was rated as the fastest ship of either side in the battle, was better armored and armed than her erstwhile squadron mates, and thus far had taken only two 5-inch (127 mm) or 6-inch (152 mm) hits. She was making 15 knots (28 km/h), and the fastest and closest U.S. ship, Brooklyn, was now six miles (10 km) behind her. Vixen was close behind Brooklyn. Armored cruiser USS New York, making 20 knots (37 km/h), was closing, and, farther behind, battleships Texas and Oregon also were making their best speed in pursuit.

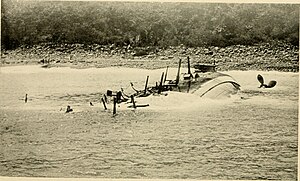

After another hour, Cristóbal Colón had run through all of her best coal, switched to an inferior grade, and began to lose speed. At 1220, Oregon fired a 13-inch (330-mm) round which landed just astern of Cristóbal Colón, and soon more 13-inch (330 mm) rounds, as well as 8-inch (203-mm) shells from Brooklyn and New York, were landing around the Spanish ship. In contrast, she had only one 6-inch (152-mm) gun that would bear on her pursuers. All told, the Spanish cruiser was hit six times.[3] When the range dropped to 2,000 yards (1,830 m), the commanding officer of Cristóbal Colón, Captain Emilio Díaz-Moreu y Quintana, decided that after a 50-mile run, the chase was over; in order to save the lives of her crew, he beached her at the mouth of the Turquino River, 75 miles (65 nmi; 121 km) west of Santiago, at 1315 hours and order his men to open the valves to scuttle the cruiser to prevent it from being captured. It was the end of the Battle of Santiago de Cuba.

Some of her sailors made it ashore, although they had to beware of Cuban insurgents, who began to shoot the survivors of the wrecked Spanish ships. Others were rescued by American sailors who came alongside the wreck in small boats to take off survivors.

Fate

That night, a U.S. Navy salvage team from repair ship USS Vulcan decided that Cristóbal Colón was worth salvaging and towed her off the rocks. The team did not notice that the ship was scuttled, only when they towed it, they realized she lacked watertight integrity and quickly capsized and sank, a total loss.

Preservation

The Naval Battle Underwater Park of Santiago de Cuba was created to preserve the wrecks of the ships and pay tribute to the sailors who perished in the Battle of Santiago de Cuba. The park permits divers to visit the wrecks.

Notes

- ^ The Spanish–American War Centennial Website: Cristobal Colon

- ^ The Spanish–American War Centennial Website: Cristobal Colon, and Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905, p. 382

- ^ Berner, Brad K. (1998). The Spanish–American War: A Historical Dictionary. Volume 8 of Historical Dictionaries of War, Revolution, and Civil Unrest. Scarecrow Press, p. 92. ISBN 0-8108-3490-1

References

![]() This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships.

- Chesneau, Roger, and Eugene M. Kolesnik, Eds. Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1860–1905. New York, New York: Mayflower Books Inc., 1979. ISBN 0-8317-0302-4.

- Nofi, Albert A. The Spanish–American War, 1898. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania:Combined Books, Inc., 1996. ISBN 0-938289-57-8.

- El condestable Zaragoza. Crónica de la vida de un marino benidormense, 1998. R. Llorens Barber. Published by Town Hall of Benidorm and University of Alicante. ISBN 84-923107-1-5