Singer Building

| Singer Building | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Record height | |

| Tallest in the world from 1908 to 1909[I] | |

| Preceded by | Philadelphia City Hall |

| Surpassed by | Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Commercial offices |

| Architectural style | Beaux-Arts and French Second Empire |

| Location | 149 Broadway, Manhattan, New York City, New York |

| Coordinates | 40°42′35″N 74°00′39″W / 40.70972°N 74.01083°W |

| Construction started | 1897 |

| Completed |

|

| Renovated | 1906–1908 |

| Demolished | 1967–1969 |

| Height | |

| Tip | 674 ft (205 m) |

| Roof | 612 ft (187 m) |

| Top floor | 41 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 41 (+1 below ground) |

| Lifts/elevators | 16 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect(s) | Ernest Flagg |

| Developer | Singer Manufacturing Company |

| Engineer |

|

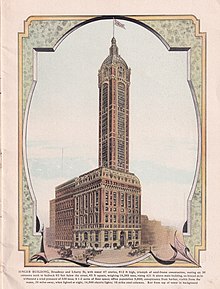

The Singer Building (also known as the Singer Tower)[a] was an office building and early skyscraper in Manhattan, New York City. The headquarters of the Singer Manufacturing Company, was at the northwestern corner of Liberty Street and Broadway in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan. Frederick Gilbert Bourne, leader of the Singer Company, commissioned the building, which architect Ernest Flagg designed in multiple phases from 1897 to 1908. The building's architecture contained elements of the Beaux-Arts and French Second Empire styles.

The building was composed of four distinct sections. The original 10-story Singer Building at 149 Broadway was erected between 1897 and 1898, and the adjoining 14-story Bourne Building on Liberty Street was built from 1898 to 1899. In the first decade of the 20th century, the two buildings were expanded to form the 14-story base of the Singer Tower, which rose another 27 stories. The facade was made of brick, stone, and terracotta. A dome with a lantern capped the tower. The foundation of the tower was excavated using caissons; the building's base rested on shallower foundations. The Singer Building used a steel frame, though load-bearing walls initially supported the original structure before modification. When completed, the 41-story building had a marble-clad entrance lobby, 16 elevators, 410,000 square feet (38,000 m2) of office space, and an observation deck.

With a roof height of 612 feet (187 m), the Singer Tower was the tallest building in the world from 1908 to 1909, when it was surpassed by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower. The base occupied the building's entire land lot; the tower's floors took up just one-sixth of that area. Despite being regarded as a city icon, the Singer Building was razed between 1967 and 1969 to make way for One Liberty Plaza, which had several times more office space than the Singer Tower. At the time of its destruction, the Singer Building was the tallest building ever to be demolished by its owners, a distinction it held until 2019.

Architecture

The Singer Building was at the northwest corner of Liberty Street and Broadway in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan, abutting the City Investing Building to the north.[3][4] The land lot was nearly rectangular, though slightly skewed due to the layout of the street grid,[5][6] and measured 74.5 feet (22.7 m) on Broadway by 110 feet (34 m) on Liberty Street.[6] The structure, as completed in 1908, was composed of four distinct sections:[7] the original Singer and Bourne buildings, an annex next to both buildings, and the tower. All of these structures were designed by Ernest Flagg for Frederick Bourne, who led the Singer Manufacturing Company.[8][9]

The structure was designed with elements of the Beaux-Arts style[10][11] and the French Second Empire style.[12] American architect George W. Conable prepared plans and working drawings.[13] An architectural office with an engineering department led by Otto F. Semsch,[4][14] and mechanical equipment engineer consultants Charles G. Armstrong and steel engineers Boller & Hodge, oversaw construction.[4] Over 40 other companies were involved in the construction process,[4] and nearly 100 construction contracts were awarded. There were no general contractors on the project; the owners communicated directly with the suppliers responsible for each contract.[15][16]

When the tower addition was completed in 1908, its roof was 612 feet (187 m) high.[17][18][19] The tower was topped by a 58-foot (18 m) flagpole, giving it a ground-to-pinnacle height of 670 feet (200 m).[18] The Singer Building was the world's tallest building at the time of its completion and the world's tallest building to be destroyed upon its demolition.[20] Contemporary sources at the time of the building's construction described the "Singer Tower" as referring only to the building's tower portion, rather than its base. The "Singer Building" name originally referred only to a portion of the base, although by the mid–20th century it referred to the entire structure.[1][2]

Form

The base of the building filled the entire lot. It was composed of the 10-story original structure (later expanded to 14 stories) and the 14-story annex known as the Bourne Building.[4] The original Singer Building, on the southeastern portion of the lot, had a frontage of 58 feet (18 m) on Broadway and 110 feet (34 m) on Liberty Street. The Bourne Building, on the southwestern portion, was 58 feet deep and had a frontage of approximately 75 feet (23 m) on Liberty Street.[21] From 1906 to 1907, the original Singer Building was extended northward and the Bourne Building was extended westward.[22] The original Singer and Bourne buildings were about 200 feet (61 m) tall.[23]

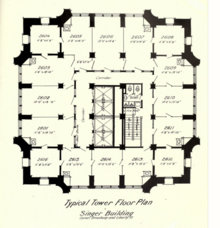

The 41-story tower above the northwest corner of the base was square in plan, with floor dimensions of 65 by 65 feet (20 by 20 m).[4][6][17] When the dome and lantern at the tower's pinnacle were included, the Singer Tower was the equivalent of a 47-story building.[4][24] The tower was set back 30 feet (9.1 m) behind the base's frontage on Broadway,[4][6] and it filled only one-sixth of the total lot area.[24] There was a gap of 10 feet (3.0 m) between the Singer Building's tower and the City Investing Building immediately to the north, which was built during the same time. The columns required to support the Singer Tower would have been too large to place atop the original Singer Building, so they were instead built in the northern portion of the lot.[3] The tower had a height-to-width ratio of 7:1, setting a record at the time of its completion.[25][26]

Facade

The facade was made of red brick, light-colored stone, and terracotta.[5] Some 733,000 square feet (68,100 m2) of terracotta was used for both the facade and the interior partitions. About five million bricks were used in the entire project, including one million in the tower section.[27][28] About 1,500 cubic feet (42 m3) of North River bluestone was also used,[28] as was 4,280,000 pounds (1,940,000 kg) of limestone, mainly above the 33rd floor.[29] The contractors for these materials included John B. Rose Company for the brick; Martin P. Lodge for the bluestone; J. J. Spurr & Sons for the limestone; and New Jersey Terra Cotta for the terracotta.[30][31][32]

For decorative elements, 101 short tons (90 long tons; 92 t) of sheet copper was used.[27] Whale Creek Iron Works provided ornamental iron while Jno. Williams Inc. provided the ornamental bronze.[2][33] There were 85,203 square feet (7,915.6 m2) of glass in the entire building, about 10 percent of which was interior glass.[27][34] There was extensive ornamentation throughout the building, including eight arches atop the tower's exterior.[35]

Base

The original Singer Building was faced with stone and brick. When it was built, the plans called for the lowest two stories to be clad with stone. The third story contained a balcony extending along both facades. The four following stories were faced with brick and contained windows with stone surrounds. The seventh story was clad with stone and had a balcony doubling as a cornice, while the facade on the eighth story was made of brick. The original top stories comprised a decorative copper-and-slate roof with dormers and stone chimneys. The main entrance was on Liberty Street and had sculptures and ornament.[36] The Bourne Building was faced with Indiana Limestone on its lowest two stories and red brick above.[37] The base had ironwork ornamentation in their mullions and window railings.[38]

After the 1906–1907 modifications, the main entrance faced Broadway on the eastern facade. This main entrance had a three-story-tall semicircular arch. A two-story architrave was beneath the arch, with an engraved cartouche reading "Singer" at the center. The upper part of the arch had a fanlight with five vertical mullions, below which was a bronze grille measuring 13 feet (4.0 m) wide and 24 feet (7.3 m) tall.[39]

As a result of the modifications, the first three stories were faced with rusticated North River bluestone.[6] Four stories were added between the seventh floor and the three-story roof during that time, and the Broadway facade was expanded from two bays to five.[2][40] With the modifications, the vertical bays were separated with vertical strips from the fourth to the 10th floors, with pediments above the sixth-floor windows. The 11th and 12th floors of the modified base consisted of two rows of small windows, with the 11th-floor windows spaced between brackets supporting a 12th-floor iron balcony. The top two stories contained dormer windows projecting from the mansard roof.[39] The sloped portions of the roof were clad with slate shingles, while glazed roof tiles covered the flat portion.[41]

Tower

The Singer Tower's facade was made of brick masonry ranging in thickness from 12 inches (300 mm) at the top to 40 inches (1,000 mm) at the base.[42] The Singer Tower contained five bays on each side, each measuring 12 feet (3.7 m) wide.[43] Construction plans show that there were 36 windows on each floor.[23] The faces of the tower were made of dark red brick, except for decorative elements such as trimmings, copings, courses, and windowsills, which were made of North River bluestone.[44] On each side, vertical limestone piers separated the outermost bays from the three center bays, dividing the facade into three vertical sections.[9][44] The outermost bays were illuminated by small windows.[9][45] The corners of the tower were made of solid masonry, which concealed the diagonal steel bracing inside.[25][45] The tower had cast-iron balconies and fascias, as well as wrought-iron jambs and mullions.[19] The use of iron balconies, as well as the large amount of glass in the facade, was inspired by the design of the Little Singer Building at 561 Broadway, built in 1904.[46]

Horizontal belt courses wrapped around the tower above the 17th, 18th, 23rd, 24th, 29th, and 30th stories, while there were terracotta balconies on each side at the 18th, 24th, and 30th stories.[6] Iron balconies also projected from the building at intervals of seven stories.[38][44] Near the top of the tower, the vertical stone bands on each side formed a tall arch evocative of the tower's dome.[47] On the 36th floor, an ornamental balcony cantilevered about 8.5 feet (2.6 m) outward on each side;[48] it was supported by brackets on the 35th floor.[23][41][49] Stone architraves surrounded the corner windows of the 36th and 37th stories, while ornate stone arches framed the center bays on the 36th through 38th stories. There were oval windows on each corner at the 38th floor. Above that level, a heavy stone cornice ran around the corners and above the arches.[41]

The top of the tower contained a 50-foot-tall (15 m) dome covering the top three stories,[6][48] capped by a lantern that measures 9 feet (2.7 m) across at its base[48] and stretches 63.75 feet (19 m) tall.[50] The dome's roof was made of slate, while the roof ornamentation, dormers, and lantern were made of copper sheeting.[47][51] In its final years, the dome's trapezoidal skylights were replaced with dormer windows.[41] The top of the lantern was 612 feet (187 m) above ground level, and a steel flagpole rose 62 feet (19 m) above the lantern, bringing the height of the Singer Tower to 674 feet (205 m) when measured from ground to tip.[38][52] The flagpole was actually 90 feet (27 m) long, but the base of the flagpole was embedded into the tower.[52] The entire exterior was lit at night by 1,600 incandescent lamps and thirty 18-inch (460 mm) projectors,[53] which were visible at distances of up to 20 miles (32 km).[27]

Structural features

Superstructure

Load-bearing walls initially supported the original Singer Building at 149 Broadway, while the Bourne Building annex at 85–89 Liberty Street had an internal steel skeleton.[4] The original Singer Building was altered between 1906 and 1908 to use a steel skeleton.[54] The entire building used 850 steel columns.[55] The columns were generally constructed in two-story segments.[54] One- to three-story-tall column segments were used on the basements, first floor, and 14th through 16th floors.[56] Rafters supported the mansard roof of the base, excluding the tower.[57] Milliken Brothers Inc. was the structural steel supplier for the project.[16][48]

The Singer Tower addition of 1906–1908 had a steel skeleton and weighed 18,365 short tons (16,397 long tons; 16,660 t).[43] The tower's columns were spaced 12 feet (3.7 m) apart on their centers.[17] Because the three center bays on each side contained windows, only the corners used diagonal bracing and, as such, were treated as square prisms.[57][58] Inside, there was another structure for the central elevator shafts, which were connected to the corners of the tower via longitudinal beams.[23][44][59] A girder supported the columns at the tower's corners at the fourth floor, while 36 columns rose from the basement into the tower.[48][60] Four pillars were placed at each corner of the tower and six more pillars were placed in the elevator shafts.[23][60] Each truss extended upward for two stories, causing the columns and braces to act as wind-resistant cantilevers.[23][57] The braces on the north and south contained 11 panels each while those on the east and west contained 10 panels.[23] The four columns at the center of the tower supported its dome.[48][61]

The superstructure was erected using two boom derricks. One of them, with a capacity of 40 short tons (36 long tons; 36 t), a 75-foot (23 m) mast, and a 65-foot (20 m) boom, lifted the steel beams from ground level to a 17th-story platform. The other was installed on the 17th floor and had a capacity of 25 short tons (22 long tons; 23 t); this derrick erected the tower's steel.[62][63] Generally, it took less than five minutes to transfer the steel from ground level to the superstructure.[63] German steel was used in the Singer Tower's framing because of Flagg's belief that German workmanship was better than that of Americans.[44][64] The tower's superstructure was intended to withstand wind pressure of 30 pounds per square foot (1.4 kPa),[61][65][66] even though the highest recorded wind pressure in the neighborhood was less than 10 pounds per square foot (0.48 kPa) at the time of the Singer Building's construction.[65][67]

The internal structure also used 4,520 short tons (4,040 long tons; 4,100 t) of Portland cement and 300,000 square feet (28,000 m2) of concrete subflooring.[34] The Singer Building's floors generally used terracotta flat arches 10 inches (250 mm) deep, and many of the internal partitions also used terracotta blocks.[42]

Foundation

The underlying layer of bedrock extended as deep as 92 feet (28 m), above which were layers of quicksand, hardpan, rocks, clay, and soil. The groundwater level was 20 feet (6.1 m) below the Singer Building.[68][69] The ground composition under the lot varied significantly, as the hardpan was compact in some places and loose in others.[70] Below the groundwater level, the saturation of the ground made it unfeasible to dig the cellar conventionally.[67] The Foundation Company excavated the tower's foundation[16][70] using pneumatic caissons.[b] The caissons were used to extract the underlying soil, then filled with concrete to create piers.[67][69][71]

Each caisson pier was designed to carry 30,000 pounds per square foot (1,400 kPa).[43] A gridiron of steel girders was placed atop the caisson piers.[72] Because of the design of the tower addition's wind-bracing superstructure, the upward pull on some of the piers was greater than the dead load these piers carried. As a result, eyebars of different lengths were embedded in 10 of the caissons, the concrete being poured onto the eyebars.[61][65][73] The rods were embedded 50 feet (15 m) into the caisson piers. The system, devised in house by Flagg's office, was more than twice as expensive as a conventional foundation would have cost for a building of the Singer Tower's size.[43][74] The original plan was for the caissons to be sunk only 20 feet (6.1 m) deep, but the builders changed plans midway through the excavations, so that the caissons would go to hardpan.[71]

The original portions of the building were built on grillages 24 feet (7.3 m) below the sidewalk level.[70] These foundations were strengthened when the tower was added.[40] The total weight of the Singer Building, including the tower addition, was carried by 54 steel columns atop the concrete foundation piers.[75]

Interior

The Singer Building was intended to be fireproof, and the tower section used mostly concrete floors, with wood used in some doors, windows, railings and decorative elements.[76][77] The base used more wood than the tower, mainly in the floors, windows, and doors.[76] All the building's stairs were made of cast iron.[19][38] The interior trim in the Singer Building was made of metal painted to resemble wood, including in the doors. Actual wooden furniture was used in the Singer Company's main offices on the 34th floor.[77][78] There were also ornamental plaster features executed by H. W. Miller Inc.[2][79] Plaster was used extensively for the walls and ceilings.[77] The usable office space in the building totaled 410,000 square feet (38,000 m2; 9.4 acres).[17]

The Singer Building took water from the New York City water supply system, where it was filtered through ammonia coils and then through two filters into two suction tanks.[80] Inside the Singer Building, there were seven water tanks to serve a projected demand of 15,000 U.S. gallons (57,000 L) each hour. Three tanks on the Singer Tower's 29th, 39th, and 42nd floors had a combined capacity of 15,000 gallons and served several portions of the tower. To provide water to the base, there was one tank of 5,000 U.S. gallons (19,000 L) in the Bourne Building and three tanks of a combined 18,000 U.S. gallons (68,000 L) in the original Singer Building.[23][81] This allowed all the offices in the tower portion to be provided with cold, hot, and ice water.[81] Two heaters in the basement provided heated water to the entire building. There was also a refrigeration plant with two pumps and a small freezing system capable of producing 500 to 1,000 pounds (230 to 450 kg) of ice daily.[82]

The Singer Building contained a vacuum steam system, although the ground-floor lobby and the basement vaults were heated by an indirect-steam system. Heating came from steel radiators on each floor; the radiators in the ground-floor banking rooms and the Singer Company's 33rd and 34th floor offices were enclosed within ornamental screens.[83] About 1,600 steam radiators were installed throughout the building.[84] As well as providing heat, the building's boilers also provided electric power to the entire building.[85] Initially, the Bourne and original Singer buildings had boilers aggregating 546 horsepower (407 kW) and power generators with a capacity of 387.5 kilowatts (519.6 hp).[86] With the 1906–1908 addition, boilers aggregating 1,925 horsepower (1,435 kW) were installed,[52][85] and generators with a capacity of 1,400 kilowatts (1,900 hp) were added, replacing the old ones. A steel smokestack at the northwest corner of the building was shared with the City Investing Building to the north.[86]

Lobby

The lobby, accessed from Broadway,[41] was finished with Pavonazzo marble and had 42 short tons (38 long tons; 38 t) of bronze work.[87][88] New York Times architectural writer Christopher Gray characterized the lobby as exuding "celestial radiance".[8] Two rows of eight square marble piers trimmed with bronze beading supported the lobby ceiling.[47][77][88] Each pier was made of Pavonazzo marble and had a border of Montarenti Sienna marble.[19] There were large bronze medallions atop each pier, depicting either the Singer Company's monogram or a needle, thread, and bobbin.[8][47][88] At the tops of the piers were decorative pendentives,[88] which supported glazed plaster domes above.[79] The pendentives were ornately decorated with gold leaf.[89] The domes' drums originally contained flat, circular amber glass lights in steel frames, which were later replaced with modern glass lighting fixtures.[77]

Immediately outside the entrance, on either side of the lobby, were stairs leading up to a balcony and down to the basement,[41][90] while the south wall contained stairs to the original Singer Building.[77][90] The stairs were made of cast iron and wrought iron, and the handrails and newel posts were made of bronze.[19] The elevators were clustered on the northern wall, opposite the stairs to the original Singer Building.[41][90][91] Each of the elevator doors in the lobby were made of four bronze leaves.[19] A balcony, trimmed with bronze, overlooked the lobby.[88] There were Italian marble stairs at the rear of the lobby which split into two flights connecting to either portion of the balcony.[77][88] A master clock on the central landing of the rear stairs controlled all the clocks in the building.[77][92] The lobby was a popular spot for meetings.[26]

There were also two secondary entrances on Liberty Street—one to the original Singer Building and one to the Bourne Building. Both secondary entrances connected to the main lobby to the north. There was retail space on the ground floor as well.[91]

Basement

The boiler room and mechanical plant were in the basement, and consisted of five boilers and five generators.[86] The boilers were clustered under the western portion of the building, while an engine room was in the center. A pump room and machine room were in the southeastern corner, with a chief engineer's office, electrician's room, and waste paper room. A compressor room was at the northeastern corner.[93]

From the basement, a corridor extended east to the safe deposit vaults.[93] There were 10 vaults used by the Safe Deposit Company of New York, within a space of 10,000 square feet (930 m2). The vaults each contained several thousand safe deposit boxes, and the vault walls were formed of several layers of steel. The door to the largest vault weighed over 16 short tons (14 long tons; 15 t). The vaults abutted three committee rooms for the company.[94]

Other floors

The 2nd through 13th floors contained offices flanking a T-shaped corridor facing away from the elevators.[77] The ceilings of these story were generally painted in white watercolor while the walls were light tan.[89] In addition, these stories contained oak trim, partitions, and decorative moldings.[19] The average story at the base contained 40 offices.[17]

The tower stories contained a U-shaped layout surrounding the elevators in the center of the building, with emergency stairs in the tower's core. In the Singer Building's tower, there were very few partitions, except for elevators and restrooms.[77][95] The average floor in the tower contained 16 offices.[17][23] On these stories, the ceilings were painted ivory,[89] the walls were olive green,[19][89] and the metal trim was painted to resemble wood grain.[19] The Singer Company's main offices, on the 33rd through 35th floors, had a plethora of ornamental plaster.[79]

The highest publicly accessible point in the Singer Building was 564 feet (172 m) above the curb, at the lantern balcony.[49] When the observation deck opened on June 23, 1908,[96] visitors paid $0.50 (equivalent to $17 in 2023) to use the observation area at the top of the building. From this observation deck, visitors could see as far as 30 miles (48 km) away.[97] After two people jumped from the deck and died, the Singer Tower was nicknamed "Suicide Pinnacle", and its deck was closed by the 1930s.[87] From the observation deck, a series of steep ladders and stairs led to the lantern.[51]

Elevators

There were 15 Otis electric traction elevators in the completed building,[98][99] and one electric-drum elevator, for a total of 16 elevators.[100][101] The tower portion had nine elevators, eight of which ran from the lobby.[15] Four were "local" elevators making all stops between the lobby and the 13th floor; two of these continued down to the basement. Four "express" elevators ran from the lobby to the upper floors; three of them terminated at the 35th floor and the fourth at the 40th floor. Another "shuttle" elevator served only the 35th through 38th floors.[15][102] The elevators could carry loads of up to 2,500 pounds (1,100 kg) and could travel from the lobby to the top floor at 600 feet per minute (180 m/min), faster than any other elevator then in existence.[98][101][103]

The base had seven elevators: four in the Bourne Building and three in the original Singer Building. Two of the elevators in the base, one each in the Bourne and original Singer buildings, served all floors from the basement to the roof. The other five ran only from the first floor to the 14th floor.[101] The original Singer Building's elevators were in a single group on the southeastern side of the building, while the Bourne Building's elevators were in two pairs opposite each other.[90] The building's managers hired female elevator operators, whom they characterized as "businesslike in appearance and polite in manner", as opposed to the "slovenly male operator with the ever-ready 'back talk'".[104] The cabs also had telephones, with which the elevator operators and starters could communicate.[105][106]

History

During the late 19th century, New York City trailed Chicago in the development of early skyscrapers; New York had just four buildings over 16 stories tall in 1893, compared to twelve such buildings in Chicago.[107] Part of the delay was caused by New York City authorities, who until 1889 would not allow metal-frame construction techniques.[108] Skyscraper development in New York City changed in 1895 with the construction of the American Surety Building, a 20-story, 303-foot (92 m) development that broke Chicago's height record. From then on, New York thoroughly embraced skeleton frame construction.[109] The early years of the 20th century saw a range of technically sophisticated, architecturally confident skyscrapers built in New York; academics Sarah Landau and Carl Condit term this "the first great age" of skyscraper development.[110]

Isaac M. Singer and Edward C. Clark had founded I. M. Singer & Company in 1851. The company, which manufactured sewing equipment, became the Singer Manufacturing Company in 1865.[111][112] The Singer Manufacturing Company was also involved in real estate during the latter half of the 19th century, Clark commissioning Henry Janeway Hardenbergh to design the Dakota and other New York City residential buildings in the 1880s. By the following decade, at the behest of Clark's son Alfred Corning Clark, the Singer Company was instead working with Ernest Flagg, then a recent graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts. Frederick Bourne, who had become the Singer Company's president in 1889, oversaw the firm's expansion into European markets during that time.[113]

Original building and annex

In February 1890, the Singer Manufacturing Company acquired the lot at 151–153 Broadway.[114] The next month, they bought the lots at 149 Broadway and 83 Liberty Street, at the northwest corner of the two streets.[114][115] The three lots had cost the company over $950,000 (equivalent to $29,407,000 in 2023), and at the time were occupied by four- to six-story buildings.[114] The three lots were separate prior to the Singer Company's acquisition but, under their ownership, were combined.[116]

The Singer Manufacturing Company hired Ernest Flagg for the design of their new headquarters. Flagg filed plans for the new Singer Building at 149 Broadway in early 1897. They called for a 10-story stone-and-brick building with banking rooms on the lowest two stories, rental office space on six of the center stories, and the Singer Company's offices on the upper stories.[36][117] Construction began that year. While workers were excavating the site in June 1897, a water main burst and flooded the lot.[118] Despite this, the new Singer Building was completed in early 1898.[4][119]

In December 1897, before the new Singer headquarters was completed, Bourne bought three five-story structures for the company at 85–89 Liberty Street, on a plot measuring 74.8 by 99.8 feet (22.8 by 30.4 m).[117][120][121] Flagg was retained to design the 14-story Bourne Building on the site, and when he submitted building plans in 1898, the annex was estimated to cost $450,000.[37][122] Bourne did not take title to the Bourne Building's site until September 1899,[123] and the Bourne Building was completed the same year.[4] By 1900, the Singer and Bourne buildings were both fully occupied.[117] The tenants included the law office of Augustus Van Wyck,[124] and the Trust Company of America.[125] Boiler manufacturers Babcock & Wilcox were long-term tenants, occupying the Singer Building for more than forty years from the beginning of the 20th century.[126]

Expansion

Further acquisitions followed in the first decade of the 20th century. In 1900, Bourne bought an iron-front building at 155 and 157 Broadway, with a frontage of about 39.8 feet (12.1 m) on Broadway.[117][120] The purchase of 163 Broadway, a house with a frontage of only 12.5 feet (3.8 m), followed in 1902,[127] and in 1903 by the purchase of the five-story 93 Liberty Street, which added a frontage of 27 feet (8.2 m).[128] By 1905, the Singer Company controlled most of the block along both Broadway and Liberty Street; the original Singer Building was an L-shaped structure extending west and then north from the northwestern corner of Broadway and Liberty Street.[129]

Tower construction

Concurrently with the land acquisitions, Flagg was retained to design a second addition to the Singer Building in 1902. By early the next year, he was planning a building that would be the tallest in the world, with over 35 stories.[4] However, the Singer Manufacturing Company did not reveal specific details until February 1906, when it announced that it would build a 594-foot (181 m) tower, the world's tallest.[97][130] Revised plans were filed in July 1906, which provided for a more wind-resistant structure.[131] The company intended to occupy the space above the 31st floor and planned to rent out the bottom section of the tower to tenants to subsidize their use of the upper floors.[4] The Singer Company projected that it would earn $250,000 in rent per year, given a baseline rental cost of $3 per square foot ($32/m2).[132] Engineers were hired to create the construction plans as soon as the architect's plans and specifications were published.[133]

Before the foundations were built, the builders drilled several test boreholes to determine the composition of the underlying soil.[24][70] Contracts for digging the foundation were awarded in August 1906 before the plans were approved.[134] The plans for the Singer Tower were approved on September 12, 1906,[135] and excavation began later that month,[68][69][135] with work officially beginning on September 19.[16][135] A timber platform, measuring 30 feet (9.1 m) wide and descending from Broadway to the excavation site, was constructed so that workers could receive materials and extract soil more efficiently.[69] The first steel shipments for the anchorages arrived in October 1906.[133] Foundation work was completed on February 18, 1907.[135]

The superstructure was constructed afterward. A temporary elevator was installed while the tower's superstructure was being erected.[136] During the construction process, city building inspectors alleged the builders had violated city law by installing concrete flooring instead of hollow-tile floors. As a result, the builders were ordered to replace some non-compliant arches.[137] By August 1907, the steel frame had reached 36 stories, surpassing the Washington Monument's height.[138] That month, Prince Wilhelm of Sweden visited the 29th floor to see the construction process.[139] On October 4, 1907, the building topped out with the hoisting of the flagpole.[140][141] After the building topped out, the interiors were furnished and plastered.[79] Despite high winds, there were no serious accidents during construction.[14] There was a small fire on the 40th floor in February 1908, which the Los Angeles Times described at the time as "the highest fire in any building in the world".[142]

Base expansion

In late 1905, Flagg was hired to design a westward annex to the Bourne Building and a northward annex to the original Singer Building. The Bourne and Singer buildings were to be united internally, and the old Singer Building was to be expanded to 14 stories.[21] The top story of the Bourne Building would also be expanded so that it would cover the same area as the Bourne Building's lower floors.[143] Plans for the Bourne and Singer extensions were filed in late 1906 and early 1907, respectively.[135]

During the construction of the Singer Tower, the original Singer Building was shored up and additional foundations were built.[40][71][144] The top three stories of the old Singer Building, including the mansard roof, were temporarily taken apart in June 1907, so that four more stories could be inserted above the existing seventh story. As such, the old eighth story of the old Singer Building became the new 12th story. This added 15,600 square feet (1,450 m2) of usable space without disturbing tenants on the lower floors.[40][145] Several columns were erected at the old building's front and rear elevations, extending from the basement to the 11th floor to support the raised roof. Holes were created in the existing floors of the Singer Building so that they could be supported by steel columns instead of by the bearing walls.[54] The old Singer Building was extended north by 74 feet (23 m), the three extra bays on Broadway having the same style as the original two.[2]

In the Bourne Building, the three existing elevators were removed and replaced with four elevators, necessitating the complete replacement of the framing around the old elevator shafts.[54] A small window replaced the main entrance to the original Singer Building.[2]

Completion and further use

On May 1, 1908, the tower was opened to the public.[68][135] The construction workers held a dinner that week to celebrate the completion of work.[146] A month later, on June 23, the observation balcony opened.[96] The Singer Building quickly became a symbol of Manhattan with its floodlit tower.[14] Surpassing Philadelphia City Hall in height, the Singer Building remained the tallest in the world for a year after its tower's completion.[147][7] The record was surpassed by the 700-foot (210 m) Metropolitan Life Insurance Company Tower,[8][7] at 24th Street and Madison Avenue.[148][c]

In the building's first few months, the elevators were involved in at least two deaths; a painter was decapitated on May 4, 1908,[149] while a plumber's assistant was crushed between an elevator cab and a shaft on July 24, 1908.[150] In a publicity stunt in 1911, the aviator Harry Atwood flew around the Singer Building.[151] The expanded building's tenants included the Chatham and Phenix National Bank, whose main office moved to the Singer Building in 1916.[152] The Safe Deposit Company of New York originally used the vaults.[94][153] The power source for the building's steam plant was converted from coal to oil in 1921, making the Singer Building the city's first office building to use oil as a fuel.[154]

In 1921, the Singer Company placed the building up for sale at an asking price of $10 million.[155] Four years later, the company made an agreement with a buyer representing the Utilities Power and Light Corporation, a holding company for several states' power companies. The transaction involved a cash deal of $8.5 million.[156][157] According to property records, the sale was never finalized.[16] Also in 1925, a subbasement vault was dug for the Chatham and Phenix National Bank after the bank's merger with the Metropolitan Trust Company, and three of the lower floors were renovated for the bank's use.[158]

The Singer Company made relatively few changes to the building; The New Yorker wrote that the firm was "wise enough to leave magnificence alone".[19] Over the Singer Building's existence, its lighting system was changed at least five times.[2][159] The copper ornamentation on the tower's dome was restored in 1939.[87] The flagpole and roof cresting were removed entirely in early 1947.[2] The building experienced an electrical fire in 1949 that forced the evacuation of the entire building, although only one person was injured.[160][161] To comply with modern building codes, automatic elevators were installed in either 1957[159] or 1959.[2] In addition, some offices received air conditioning, though they retained their original thermostats.[159] The revolving doors at the base had been removed by 1958, being replaced with standard doors. Toward the end of its existence, the Singer Building's two large ground-level storefronts were subdivided into smaller ones.[2]

Demolition

Taller buildings continued to be constructed in New York City; by its 50th anniversary in 1958, the Singer Building was only the 16th tallest in the city.[162] Singer announced it would sell the building in 1961, and the company moved to 30 Rockefeller Plaza.[163][164] According to property records, Iacovone Rose bought the Singer Building and immediately sold it to Financial Place Inc.[16] Real estate developer William Zeckendorf acquired the building and attempted to convince the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) to move there.[26][165] The plans failed after the NYSE opted to expand its existing headquarters instead. Even so, the construction of the World Trade Center nearby in the mid-1960s caused real-estate values in Lower Manhattan to increase dramatically.[26] In 1964, United States Steel bought the Singer and City Investing buildings.[165] U.S. Steel planned to demolish the entire block to erect a 50- or 54-story headquarters on the same site.[159][166] Meanwhile, under U.S. Steel's ownership, the Singer Building began to decay.[159]

The New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission (LPC) was created in 1965,[167] in the wake of several notable buildings in the city having either been demolished or threatened with demolition.[168] Although the Singer Building was considered to be one of the most iconic buildings in New York City,[169] the LPC never considered designating it as a landmark, which would have prevented the building's demolition.[25] In August 1967, LPC executive director Alan Burnham said that, if the building were to have been made a landmark, the city would have to either find a buyer or acquire the building on its own.[169][170] Sam Roberts later wrote in The New York Times that the Singer Building had been one of the city's notable structures that "weren't considered worth preserving".[171] Demolition had commenced by September 1967,[172] despite protests by Architectural Forum magazine and other preservationists, who suggested incorporating the lobby into the U.S. Steel Building.[173][26] A writer for The New York Times observed in March 1968 that the lobby looked like "a bomb had hit it".[14] The last piece of scrap had been carted away in early 1969, when the Daily News observed: "The Singer fell victim to a malady called progress."[174]

The U.S. Steel Building (later known as One Liberty Plaza) was built on the site and completed in 1973.[91] One Liberty Plaza contained 37,000 square feet (3,400 m2) per floor, compared with the 4,200 square feet (390 m2) per floor in the Singer Building's tower.[8] One Liberty Plaza had at least twice the two former buildings' combined interior area.[175] At the time of the Singer Building's demolition, it was the tallest building ever to be destroyed.[20][26][176][177] The record was surpassed during the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, which caused the collapse of the nearby World Trade Center.[5] The Singer Building remained the tallest building to be destroyed by its owners[178] until 2019, when workers started demolishing the 707-foot-tall (215 m) 270 Park Avenue in Midtown Manhattan.[179] In the 21st century, the Singer Building became a subject of the unfounded Tartaria conspiracy theory, which claimed that the skyscraper was evidence of a long-lost civilization.[180][181]

Impact

Flagg, a noted critic of existing skyscrapers, justified taking on the project as a way of generating support for skyscraper reform, by convincing the public that such tall skyscrapers were detrimental because they blocked light from reaching the surrounding streets.[182] As late as 1904, one architectural magazine wrote that "ten stories were his limit".[183] According to Flagg, buildings over 100 feet (30 m) tall, or 10 to 15 stories, needed to have a setback tower occupying no more than a quarter of the lot.[1][45][116] He had once written, "Our rooms and offices are becoming so dark that we must use artificial light all day long."[3] The Singer Building's design expressed Flagg's opinions on city planning and skyscraper design.[116] The building's design partly influenced the city's 1916 Zoning Resolution, which required many skyscrapers in New York City to have setbacks as they rose.[91][159] For over four decades, the ordinance prevented the city's new skyscrapers from overwhelming the streets with their sheer bulk.[d] These setbacks were not required if the building occupied 25 percent or less of its lot area.[91]

New York Times architectural critic Christopher Gray said in 2005 that the Singer Building's tower resembled "a bulbous mansard and giant lantern".[8] Architectural writer Jason Barr stated in 2016 that the Singer Building was a "transitional building" in skyscraper development.[5] Landau and Condit described the building as "an aesthetic triumph that enriched the city by demonstrating the sculptural possibilities of the steel-framed skyscraper".[91] Architectural Forum wrote in 1957 that the Singer Building was a "very coherent, virile piece of design".[7] Just before the building's demolition, Architectural Forum wrote that the building was "distinguished for more than mere height".[25] Ada Louise Huxtable said, "The master never produced a more impressive ruin than the Singer Building under demolition."[186][187]

Not all critics appraised the Singer Building positively. The New York Globe in the 1900s had called the Singer Building an "architectural giraffe" and said such a tall building would hinder the ability of fire services to rescue people on the upper floors.[14]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ The "Singer Tower" name generally referred only to the Singer Building's tower, which covered a small portion of the land lot.[1][2]

- ^ The building's chief engineer cites 30 caissons,[71] but the number of caissons is also cited as thirty-four.[6][72]

- ^ Although the Singer Tower was the world's tallest building, it was not the tallest structure, nor was the Metropolitan Life Tower upon its completion. The Eiffel Tower, which was 1,063 feet (324 m) tall, superseded both buildings in this respect.[5]

- ^ As per the 1916 Zoning Act, the wall of any given tower that faces a street could only rise to a certain height, proportionate to the street's width, at which point the building had to be set back by a given proportion. This system of setbacks would continue until the tower reaches a floor level when that level's floor area was 25% that of the ground level's area. After that 25% threshold was reached, the building could rise without restriction.[184] This law was superseded by the 1961 Zoning Resolution, which allowed skyscrapers to have a slab-like shape and additional floor area in exchange for the inclusion of ground-level open spaces.[185]

Citations

- ^ a b c Semsch 1908, p. 9.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Historic American Buildings Survey 1969, p. 89.

- ^ a b c Gray, Christopher (March 29, 2012). "The Hemming In of the Singer Tower". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Landau & Condit 1996, p. 355.

- ^ a b c d e O'Connor, William (April 30, 2016). "The Life and Death of The World's Tallest Building". The Daily Beast. Archived from the original on July 26, 2017. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Historic American Buildings Survey 1969, p. 92.

- ^ a b c d Architectural Forum 1957, p. 118.

- ^ a b c d e f Gray, Christopher (January 2, 2005). "Streetscapes: Once the Tallest Building, But Since 1967 a Ghost". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Charles Scribner's Sons Building" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. March 23, 1982. p. 4. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved March 31, 2021.

- ^ Stern, Gilmartin & Massengale 1983, p. 170.

- ^ White, Willensky & Leadon 2010, p. 43.

- ^ Pile 2005, p. 310.

- ^ Gobrecht, Larry E. (April 1983). "National Register of Historic Places Registration: Jamaica Chamber of Commerce Building". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. Archived from the original on October 18, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Fried, Joseph P. (March 27, 1968). "End of Skyscraper: Daring in '08, Obscure in '68". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 15, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ripley 1907, p. 9461.

- ^ a b c d e f Historic American Buildings Survey 1969, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e f Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1908, p. 429.

- ^ a b "Singer Building". The Skyscraper Center. Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat. Archived from the original on June 12, 2020. Retrieved July 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Progressive Architecture 1967, p. 170.

- ^ a b Hiler, Katie (June 17, 2013). "Once Tallest Standing, Then the Tallest to Come Down". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 13, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, p. 10.

- ^ Semsch 1908, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Already Highest Structure in the World; Yet the Colossal New Singer Building Will Rise One Hundred Feet, Or Eight Stories, Higher When Completed Its Gigantic Steel Tower Will Dwarf City's Famous Skyscrapers to Insignificance". The New York Times. August 25, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 11, 2018. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c Ripley 1907, p. 9459.

- ^ a b c d Architectural Forum 1967, p. 107.

- ^ a b c d e f Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1126.

- ^ a b c d "Buildings as Big as a Town". The New York Sun. June 28, 1908. p. 22. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, p. 35.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 38.

- ^ Historic American Buildings Survey 1969, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Semsch 1908, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1908, pp. 443–444.

- ^ Semsch 1908, pp. 33, 52.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 67.

- ^ a b "The New Singer Building". The New York Times. January 10, 1897. p. 7. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Office Buildings Underway" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 62, no. 1603. December 3, 1898. p. 828. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c d Semsch 1908, p. 33.

- ^ a b Historic American Buildings Survey 1969, p. 93.

- ^ a b c d "Slicing a Skyscraper" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 79, no. 2050. June 29, 1907. p. 824. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b c d e f g Historic American Buildings Survey 1969, p. 94.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, p. 36.

- ^ a b c d Landau & Condit 1996, p. 358.

- ^ a b c d e Landau & Condit 1996, p. 359.

- ^ a b c Architectural Forum 1957, p. 120.

- ^ Architectural Forum 1957, p. 117.

- ^ a b c d Landau & Condit 1996, p. 360.

- ^ a b c d e f Semsch 1908, p. 20.

- ^ a b Engineering Record 1907, p. 630.

- ^ Engineering Record 1907, p. 542.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1908, p. 434.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Semsch 1908, p. 32.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 21.

- ^ Engineering Record 1907, p. 599.

- ^ a b c Engineering Record 1907, p. 602.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 358–359.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 22.

- ^ a b Engineering Record 1907, pp. 542–543.

- ^ a b c Engineering Record 1907, p. 543.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, p. 442.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, p. 28.

- ^ "Why Steel Is Imported". Engineering News-Record. Vol. 65. June 22, 1911. p. 765. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Anchorage of Singer Building Tower" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 79, no. 2041. April 27, 1907. p. 824. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1908, p. 430.

- ^ a b c Ripley 1907, p. 9460.

- ^ a b c Landau & Condit 1996, p. 357.

- ^ a b c d Engineering Record 1907, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d Semsch 1908, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d Semsch 1908, p. 13.

- ^ a b Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1908, p. 432.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 15.

- ^ "How the New Singer Building Is to Be Anchored to the Earth" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 78, no. 2017. November 10, 1906. p. 766. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 16.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Historic American Buildings Survey 1969, p. 95.

- ^ Semsch 1908, pp. 74, 76.

- ^ a b c d Semsch 1908, p. 68.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 56.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Semsch 1908, pp. 92, 99.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 63.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 65.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, p. 87.

- ^ a b c Semsch 1908, pp. 80–81.

- ^ a b c "New Copper Trimmings Fitted On Dome of the Singer Building". New York Herald Tribune. November 14, 1939. p. 20. ProQuest 1320004518.

- ^ a b c d e f Semsch 1908, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d Semsch 1908, p. 72.

- ^ a b c d Semsch 1908, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d e f Landau & Condit 1996, p. 361.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 75.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, pp. 84–85.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 71.

- ^ a b "Singer Tower Open to Public". New-York Tribune. June 24, 1908. p. 6. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Landau & Condit 1996, p. 354.

- ^ a b "Up 41-Story Skyscraper in 60 Seconds". Buffalo Courier. March 24, 1907. p. 27. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1908, p. 435.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 360–361.

- ^ a b c Semsch 1908, p. 46.

- ^ "Elevators in the Singer Building" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 80, no. 2063. September 28, 1907. p. 475. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Architects' and Builders' Magazine 1908, p. 436.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (June 7, 1998). "Streetscapes/Readers' Questions; Lamartine Place, And Women Running Elevators". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on May 27, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "The Metropolitan Elevators" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 86, no. 2185. January 29, 1910. p. 216. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Semsch 1908, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Willis 1995, p. 50.

- ^ Willis 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Condit 1968, p. 119.

- ^ Landau & Condit 1996, pp. 298, 395.

- ^ Jorgensen 1994, p. 501.

- ^ Meighan 2012, p. 119.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (June 29, 1997). "Style Standard for Early Steel-Framed Skyscraper". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Real Estate Department" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 45, no. 1148. March 15, 1890. pp. 367–368. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "The Real Estate Field; Some Encouraging Signs in the Course of Business". The New York Times. September 15, 1895. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b c Historic American Buildings Survey 1969, p. 87.

- ^ a b c d "Gossip of the Week" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 65, no. 1676. April 28, 1900. p. 725. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ "An Excavation Flooded". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. June 4, 1897. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2020 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ^ "Thirty Years of Office Building" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 61, no. 1569. April 9, 1898. p. 642. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ a b "In the Real Estate Field; 155 and 157 Broadway Bought by Singer Manufacturing Company. Property Adjoins Present Singer Building—Other Dealings by Brokers and at Auction". The New York Times. April 24, 1900. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 7, 2019. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Real Estate; Valuable Downtown Building Sacrificed at Auction". New-York Tribune. December 9, 1897. p. 10. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 6, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Addition to the Singer Building". The New York Times. June 2, 1898. p. 10. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Real Estate News". The New York Sun. September 28, 1899. p. 11. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Soul of Wit". The Brooklyn Citizen. December 10, 1898. p. 1. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved July 17, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "New Trust Company Formed; Ex-Controller Fitch to Be Its President—Its Capital of $2,500,000 Oversubscribed Three Times". The New York Times. May 23, 1899. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Rent 4 Floors to Expand Singer Building Offices". The New York Times. December 18, 1939. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "In the Real Estate Field; Subway Company Buys More Park Avenue Houses—No. 163 Broadway Sold to Singer Company". The New York Times. May 2, 1902. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "In the Real Estate Field; Singer Manufacturing Company Buys 93 Liberty Street—Other Dealings by Brokers and at Auction". The New York Times. March 19, 1903. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Liberty Street's Future West of Broadway; Influence of Cortlandt Street Tunnel and Other Improvements—Significance of a Recent Lease—Transfers Showing Present Scale of Values". The New York Times. March 26, 1905. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Highest of All". New-York Tribune. February 24, 1906. p. 12. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Changes in Singer Tower; New Plans Filed by the Architect Will Make the Building Stronger". The New York Times. July 7, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ "Dollars-And-Cents Side of Forty-Story Tower; Gigantic Structure to Be Built Primarily as a Money-Maker". The New York Times. March 4, 1906. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ a b Semsch 1908, p. 30.

- ^ "Huge Structure Under Way". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. August 19, 1906. p. 13. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 13, 2020 – via Brooklyn Public Library; newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c d e f Semsch 1908, p. 11.

- ^ Semsch 1908, p. 48.

- ^ "Pick Flaws in Skyscraper". The New York Times. May 16, 1907. p. 11. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Highest of Skyscrapers". Buffalo Evening News. August 27, 1907. p. 4. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Prince Sees City From a High Point; Wilhelm, Taken to Twenty-Ninth Floor of Singer Building, Is Much Impressed". The New York Times. August 30, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "In Highest New York; Young Steeple Jack to Put Copper Ball on the Singer Tower Flagstaff". The New York Times. October 5, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Gotham's Tallest Flagpole Set". New-York Tribune. October 6, 1907. p. 9. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Highest Fire in World: Blaze on Fortieth Floor of Singer Building Is Quickly Put Out, However". Los Angeles Times. February 18, 1908. p. I1. ProQuest 159125760.

- ^ "Estimates Receivable" (PDF). The Real Estate Record: Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. Vol. 75, no. 1830. March 11, 1905. p. 522. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 28, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via columbia.edu.

- ^ Engineering Record 1907, pp. 275–276.

- ^ "Slicing a Skyscraper; Top of the Singer Building to Be Cut Off for a Three-Story Addition". The New York Times. June 14, 1907. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Skyscraper Men Dine". The New York Times. May 6, 1908. p. 9. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Haughey 2018, p. 235.

- ^ Dunlap, David W. (August 22, 2001). "Commercial Real Estate: A Tower's Big-Time Restoration; MetLife's Immense Clock Gets a Detailed Overhaul". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ "Head Cut Off by Elevator". The New York Times. May 4, 1908. p. 2. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Singer Building Elevator Kills a Workman". New York Evening World. July 24, 1908. p. 4. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 16, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Atwood's Remarkable Flight". Cycle and Automobile Trade Journal. No. v. 16. Chilton Company. 1911. p. 290. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ "Big Bank Will Move; The Chatham and Phenix to Take Quarters in the Singer Building". The New York Times. December 23, 1916. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on August 11, 2020. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Singer Company in Control; Safe Deposit Company of New York to Have Vaults in Singer Building". The New York Times. May 13, 1908. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 17, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Singer Building to Use Oil Instead of Coal Fuel". New-York Tribune. July 24, 1921. p. 30. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Any One Want Real Skyscraper? Singer Tower Is For Sale". New-York Tribune. July 24, 1921. p. 31. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "$8,500,000 Deal On for the Singer Building, With 41-Story Tower, Once World's Tallest". The New York Times. April 14, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "$8,500,000 Deal Is Under Way For 41-Story Singer Building". The New York Herald, New York Tribune. April 14, 1925. p. 1. ProQuest 1113064043.

- ^ "$250,000,000 Moved as Police Line Path; Armed Autos Also Guard Transfer of Treasure to New Bank in Singer Building". The New York Times. March 16, 1925. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 29, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f Progressive Architecture 1967, p. 171.

- ^ "Singer Building Darkened by Fire; One Man Burned, 8 Rescued From Stalled Elevators—Smoke Disrupts Business". The New York Times. April 22, 1949. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "3,500 Evacuate Singer Building As Power Fails: Short Circuit and Blaze Just Before Noon Puts Out Lights, Halts Elevators Fires in Downtown Skyscraper and a Tenement Keep Firemen on the Move". New York Herald Tribune. April 22, 1949. p. 22. ProQuest 1326786063.

- ^ "Singer Building, Once Highest In World, Marks 50th Birthday". The New York Times. April 13, 1958. p. R1. ISSN 0362-4331. ProQuest 114455893.

- ^ "Singer Rents Six Floors In Center: Firm Will Move There in 1962". New York Herald Tribune. November 17, 1961. p. 38. ProQuest 1325841053.

- ^ "Singer to Move Uptown, Sell Broadway Building". The New York Times. November 16, 1961. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 14, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ a b "Siteon Broadway Goes to U.S. Steel; Webb & Knapp Sells 2 Blocks Stock Exchange Spurned". The New York Times. March 19, 1964. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 28, 2022. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Fried, Joseph P. (April 5, 1968). "U.S. Steel To Erect a 54-Story Skyscraper Here; Lower Broadway Project Is Hailed by City as 'Great Planning Achievement'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 8, 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (April 15, 1990). "Architecture View; A Commission That Has Itself Become a Landmark". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020. Retrieved August 17, 2020.

- ^ Hanson, Kitty (December 11, 1964). "Bob's New Law Last Chance for City Landmarks". New York Daily News. p. 214. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b Fried, Joseph P. (August 22, 1967). "Landmark on Lower Broadway to Go; End Near for Singer Building, A Forerunner of Skyscrapers". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, pp. 1126–1127.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (April 23, 2015). "'Saving Place' Exhibition Celebrates New York Landmarks, Saved and Lost". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ "Singer's Swan Song". New York Daily News. September 15, 1967. p. 609. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved August 13, 2020 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Architectural Forum 1967, p. 108.

- ^ Leahy, Jack (March 2, 1969). "They're Tearing New York Down". New York Daily News. pp. 20, 22 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ Gray, Christopher (August 29, 2013). "Twins, Except Architecturally". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on October 19, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2020.

- ^ "The Beautiful Landmarks You Won't Believe Were Torn Down – and What Replaced Them". The Telegraph. October 17, 2018. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Kelly, Jon (December 6, 2012). "How Do You Demolish a Skyscraper?". BBC News Magazine. BBC. Archived from the original on December 8, 2012. Retrieved December 12, 2012.

- ^ Warerkar, Tanay (May 14, 2018). "NYC Is Home to 23 of the World's Tallest Intentionally Demolished Buildings". Curbed NY. Archived from the original on October 11, 2020. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Kim, Elizabeth (January 8, 2020). "270 Park Avenue, A Quintessential Modernist Skyscraper, Is Being Slowly Destroyed By Chase Bank". Gothamist. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved August 12, 2020.

- ^ Hatherley, Owen (October 21, 2021). "Amerikanist Dreams". London Review of Books. Vol. 43, no. 20. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Mortice, Zach (April 27, 2021). "Inside the 'Tartarian Empire,' the QAnon of Architecture". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on February 23, 2022. Retrieved February 28, 2022.

- ^ Fenske 2005, p. 22.

- ^ Desmond, H. W. (March 1904). "A Rational Desmond". Architectural Record. Vol. 15. p. 279. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Kayden & The Municipal Art Society of New York 2000, p. 8.

- ^ Kayden & The Municipal Art Society of New York 2000, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Byles, Jeff (January 22, 2006). "The Romance of the Wrecking Ball". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2020.

- ^ Stern, Mellins & Fishman 1995, p. 1127.

Sources

- "As Ye Sew, So Shall They Reap" (PDF). Progressive Architecture. Vol. 48. September 1967.

- Condit, Carl W. (1968). American Building: Materials and Techniques from the Beginning of the Colonial Settlements to the Present. University of Chicago Press. OCLC 600614625.

- Fenske, Gail (2005). "The Beaux-Arts Architect and the Skyscraper: Cass Gilbert, the Professional Engineer, and the Rationalization of Construction in Chicago and New York". In Moudry, Roberta (ed.). The American Skyscraper: Cultural Histories. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-52162-421-3. OCLC 56752831.

- "Forgotten Pioneering" (PDF). Architectural Forum. Vol. 106. April 1957.

- Haughey, Patrick, ed. (2018). A History of Architecture and Trade. Routledge Research in Architecture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-79679-8.

- Historic American Buildings Survey Selections. Vol. 7. Historic American Buildings Survey. 1969.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - Jorgensen, Janice, ed. (1994). Encyclopedia of Consumer Brands. Vol. Durable Goods. St. James Press. ISBN 978-1-55862-338-5.

- Kayden, Jerold S.; The Municipal Art Society of New York (2000). Privately Owned Public Space: The New York City Experience. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-36257-9.

- Landau, Sarah; Condit, Carl W. (1996). Rise of the New York Skyscraper, 1865–1913. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-07739-1. OCLC 32819286.

- "Landmarks: Too Good to Last" (PDF). Architectural Forum. Vol. 127. July–August 1967.

- Meighan, Michael (2012). Scotland's Lost Industries. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-2401-3.

- Pile, John F. (2005). A History of Interior Design. Laurence King. ISBN 978-1-85669-418-6.

- Ripley, Charles M. (October 1907). "A Building Forty-Seven Stories High". The World's Work: A History of Our Time. Vol. XIV. pp. 9459–9461.

- Semsch, Otto Francis (1908). A History of the Singer Building Construction, Its Progress From Foundation to Flag Pole. The Trow Press.

- "The Singer Building, New York". Architects' and Builders' Magazine. Vol. 40, no. 10. July 1908. pp. 429–444.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Gilmartin, Gregory; Massengale, John Montague (1983). New York 1900: Metropolitan Architecture and Urbanism, 1890–1915. Rizzoli. ISBN 0-8478-0511-5. OCLC 9829395.

- Stern, Robert A. M.; Mellins, Thomas; Fishman, David (1995). New York 1960: Architecture and Urbanism Between the Second World War and the Bicentennial. Monacelli Press. ISBN 1-885254-02-4. OCLC 32159240.

- "Volume 55". Engineering Record. Vol. 55. 1907.

- "Methods Used in Underpinning the Singer Building, New York". Engineering Record. Vol. 55. March 2, 1907. pp. 275–276.

- "Steel Details in the Upper Part of the Singer Building Tower". Engineering Record. Vol. 55. May 25, 1907. pp. 630–632.

- "Structural Details of the Singer Building, New York". Engineering Record. Vol. 55. May 18, 1907. pp. 599–602.

- "The Anchorages of the Singer Building Tower". Engineering Record. Vol. 55. May 4, 1907. pp. 542–543.

- "The Foundations of the Singer Building Extension, New York". Engineering Record. Vol. 55. February 2, 1907. pp. 116–118.

- White, Norval; Willensky, Elliot; Leadon, Fran (2010). AIA Guide to New York City (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19538-386-7.

- Willis, Carol (1995). Form Follows Finance: Skyscrapers and Skylines in New York and Chicago. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1-5689-8044-7.

External links

Media related to 149 Broadway Singer Building at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to 149 Broadway Singer Building at Wikimedia Commons- "Emporis building ID 102519". Emporis. Archived from the original on March 10, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - "Singer Building". SkyscraperPage.

- Singer Building at Structurae