Silver mining

Silver mining is the extraction of silver by mining. Silver is a precious metal and holds high economic value. Because silver is often found in intimate combination with other metals, its extraction requires the use of complex technologies. In 2008, approximately 25,900 metric tons of silver were consumed worldwide, most of which came from mining.[1] Silver mining has a variety of effects on the environment, humans, and animals.

Silver sources

Silver-bearing ore typically contains very little silver, with much higher percentages of copper and lead. Specific minerals include argentite (Ag2S), chlorargyrite ("horn silver," AgCl), polybasite (Ag, Cu)16Sb2S11), and proustite (Ag3AsS3).[2] Silver mainly occurs as a contaminant in chalcopyrite and galena, important ores of copper and lead, respectively.[3][4][5]

Some ores are actually mined explicitly for their silver value vs. the silver being a byproduct of other metals. However, silver is only found rarely in a native form as nuggets, in placer deposits, and veins.[6]

Excavation

Methods for mining silver change for every body of ore. The method that's chosen depends on the grade of the ore, the steepness and shape of the terrain, its depth, host rock, transportation availability, and other economic factors.[7] Commonly, silver ore is obtained from open pit mines, and underground drifts and shafts.[7] Explosives are frequently used to shatter veins into manageable pieces, which are transported via mine cars and then lifted to the surface.[7][6] This process can be dangerous.[8]

Ore processing

Once removed from the mine, silver-containing ore is crushed (comminution) into a fine powder to expose individual grains to chemical processing. As a byproduct of the mining of lead and copper, silver ores are often purified by froth flotation. After froth flotation, silver is extracted by a cyanide process, akin to technology used for gold extraction.[1] In some cases, the ore is treated by smelting before cyanide treatment. Silver is also produced during the electrolytic refining of copper and by application of the Parkes process on lead ores. Commercial grade fine silver is at least 99.9 percent pure silver, and purities greater than 99.999 percent are available.

Silver scrap processing

Recycling

About 5000 tons of silver are annually recovered from scrap.[1] Jewelry, photographic film, silverware, coins, and electronics are sources of recyclable silver.[7] However, jewelry and silverware are not as important of a source of recycled metal compared to electronics and photographic film.[7] The main techniques to process silver scrap: electrolysis, metallic replacement, and precipitation. Electrolytic silver recovery refers to the process where silver cations are reduced to their metallic state, adhering to an electrode.[7]

In metallic replacement, a solution of silver thiosulfate is converted to the metallic state by the action of a solid reducing agent, such a steel wool. The equipment in this process is commonly referred to as "metallic recovery cartridges".[7]

Precipitation refers to the process of extracting silver from silver-rich solutions. This technique uses precipitating agents to form silver sulfide in the solution. The precipitation method is not extensively utilized due to the fact that excess sulfide can result in the release of toxic gas.[7]

Production areas

The principal sources of silver are copper, copper-nickel, gold, lead, and lead-zinc ores obtained from Canada, Mexico,[9] Poland, Peru, Bolivia, Australia[10] and the United States.[11]

Mexico was the world's largest silver producer in 2014, producing 5,000 metric tons (161 million troy ounces), 18.7 percent of the 26,800 tonnes (862 million troy ounce) production of the world.[12]

| Mine | Country | 2010 Production | 2020 Production |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cannington Silver/Lead/Zinc Mine | Australia | 38.6 Moz | 11.792 Moz |

| Fresnillo Silver Mine | Mexico | 38.6 Moz | 13.055 Moz |

| San Cristobal Polymetallic Mine | Bolivia | 19.4 Moz | |

| Antamina Copper/Zinc Mine | Peru | 14.9 Moz | |

| Rudna Copper Mine | Poland | 14.9 Moz | |

| Peñasquito Polymetallic Mine | Mexico | 13.9 Moz |

| Project | Country | Anticipated Annual Production Capacity (due within five years) |

|---|---|---|

| Pascua Lama | Chile | 25.0 Moz |

| Navidad | Argentina | 15.0 Moz |

| Juanicipio | Mexico | 14.0 Moz |

| Malku Khota | Bolivia | 13.2 Moz[15] |

| Hackett River | Canada | 13.1 Moz |

| Corani | Peru | 10.0 Moz |

Silver mining companies

Silver mining companies engage in the discovery and production of silver.[16] While these companies prioritize in silver, many of them also engage in other metals such as gold, palladium, lead, and zinc.[16]

| Company Name | Revenue | Net Income | Exchange |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrias Penoles SAB de CV (IPOAF) | $5.57 billion | $89.25 million | OTC |

| Polymetal International PLC (AUCOY) | $2.67 billion | $164 million | OTC |

| Fresnillo PLC (FNLPF) | $2.50 billion | $236.46 million | OTC |

| Pan American Silver Corp. (PAAS) | $1.54 billion | $154.956 million | NASDAQ |

| Wheaton Precious Metals Corp. (WPM) | $1.11 billion | $794.82 million | New York Stock Exchange |

| Buenaventura Mining Co. Inc. (BVN) | $831.79 million | $351.70 million | New York Stock Exchange |

| Coeur Mining Inc. (CDE) | $783.40 million | $137.96 million | New York Stock Exchange |

| Fortuna Silver Mines Inc. (FSM) | $715.70 million | $40.39 million | New York Stock Exchange |

| Hecla Mining Co. (HL) | $709.16 million | $21.02 million | New York Stock Exchange |

| First Majestic Silver Corp. (AG) | $684.12 million | $101.43 million | New York Stock Exchange |

History

The historical record of silver mining dates back to 3,000 BC in Anatolia.[17] As silver is a precious metal often used for coins and bullion, its mining has historically often been lucrative. As with other precious metals such as gold or platinum, newly discovered deposits of silver ore have sparked silver rushes of miners seeking their fortunes. Silver was a valuable metal that helped early civilizations around Ancient Greece.[17] In recent centuries, large deposits were discovered and mined in the Americas, influencing the growth and development of Mexico, Andean countries such as Bolivia, Chile and Peru, as well as Argentina, Canada and the United States.

Silver is mentioned in the Book of Genesis, and slag heaps found in Asia Minor and on the islands of the Aegean Sea indicate that silver was being separated from lead as early as the 4th millennium BC. By 1,200 BC, silver mining shifted into the mines of Laurion in Greece, and continued growing the surrounding empire.[17] The silver mines at Laurion were very rich[18] and helped provide a currency for the economy of ancient Athens, where the process involved mining the ore in underground galleries, washing and then smelting it to produce the metal. Elaborate washing tables still exist at the site which used rain water held in cisterns and collected during the winter months.[citation needed]

By the year 100 AD, the epicenter of silver mining transitioned into Spain, where the Roman Empire flourished.[17] The Romans took over silver mining in Spain from Carthage after their acquisition of Carthaginian territories there following the Second Punic War. Extraction of silver from lead ore was widespread in Roman Britain very soon after the Roman conquest of the first century AD.

One of the main aims of the Viking expansion throughout Europe was to acquire and trade silver.[19][20] Bergen and Dublin are still important centres of silver making.[21][22] An example of a collection of Viking-age silver for trading purposes is the Galloway Hoard.[23]

From the mid-15th century silver began to be extracted from copper ores in massive quantities using the liquation process creating a boost to the mining and metallurgy industries of Central Europe.[24]

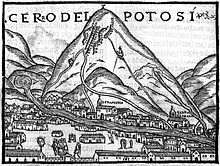

Americas

Vast amounts of silver were brought into the possession of the crowns of Europe after the conquest of the Americas from the now Mexican state of Zacatecas (discovered in 1546)[25] and Potosí (also discovered in 1546), which triggered the Spanish Price Revolution in Europe. Between 1500 and 1800, Bolivia, Peru, and Mexico made of 85% of the world's total silver production.[17] Silver mining required large amounts of mercury to extract the metal from ore. In the Andes, the source was the Huancavelica mercury mine; Mexico was dependent on mercury from the Almadén mercury mine in Spain. Mercury had a high adverse environmental impact.[26] Silver was extremely valuable in China, and became a global commodity. Manila galleons carried Spanish dollars across the Pacific, contributing to the rise of the Spanish Empire. The rise and fall of its value affected the world market.

In the first half of the 19th century Chilean mining revived due to a silver rush in the Norte Chico region, leading to an increased presence of Chileans in the Atacama desert and a shift away from an agriculture based economy.

The country of Argentina was named after its silver resources by Spanish conquistadors; Argentina is a Spanish adjective meaning "silvery".[27]

Silver mining was a driving force in the settlement of western North America,[28] with major booms for silver and associated minerals (lead, mostly) in the galena ore silver is most commonly found in. Notable silver rushes were in Colorado; Nevada; Cobalt, Ontario; California and the Kootenay region of British Columbia; notably in the Boundary and "Silvery" Slocan. A silver rush in Idaho produced mines in an area known as Silver Valley, a handful of which are still active today.[29] The first major silver ore deposits in the United States were discovered at the Comstock Lode in Virginia City, Nevada, in 1859. By the 1870's, silver production had increased from 40 millions ounces per year to 80 million.[17]

From 1872 to 1920, a surge of technological innovation increased global silver production to 120 million ounces produced per year.[17] New silver deposits had been discovered in Australia, Canada, United States, Africa, Mexico, Chile, and Japan, and by the end of 1920, global production surged to 190 million ounces annually.[17] The mining techniques during the 1900's had also dramatically changed. Seam-assisted drilling, mine dewatering, and improved haulage all contributed to the spike in silver production in the 1900's.[17] By 2019, technological innovation has allowed silver production to grow to almost 800 million ounces per year.[17]

Environmental effects of silver mining

Mercury amalgamation

Mercury amalgamation is a technique used to extract gold and silver from lower-grade ores. Mercury quickly sticks to gold and silver and forms pasty amalgams, making extraction easier.[30] After separating it from the ore, amalgam is roasted and mercury vapor escapes into the atmosphere and also makes its way into rivers and soils.[30] From the years 1545 to 1803, over 25,000 tons of silver were produced using amalgamation in the Potosi mines.[30] At its peak, the town had over 6,000 smelting furnaces spreading toxic Mercury.[30] Mercury-rich tailings are also often left in mines.[30]

The amalgamation methods have proven problematic. It is estimated that 90% of the mercury consumed in the United States from 1850 to 1900 was used to extract silver and gold.[31] An estimated 257,400 tonnes of mercury were lost to the environment in this process in the Americas since the patio process was first used. 60-65% of this is likely released into the atmosphere, being the single largest contributor to the global mercury cycle.[31]

In the year 2000, small-scale miners in Chile experienced many risks to their health, safety, and hygiene from toxic pollution. This was due to wastewater being released into underground waters and creating significant quantities of mercury.[32]

Contaminants are also known to enter drinking water in and around abandoned silver mines. Well water in South Morelos State, Mexico, was found to have high concentrations of toxic minerals including arsenic, iron, manganese, lead, and fluorine.[33] This is attributed to the abandoned and flooded silver mine at Huautla. Groundwaters flooded the mine-shafts after they were abandoned in the early 1990s, which allowed for oxidation and mobilization of these dangerous contaminants.

Effects of silver mining on Indigenous communities

Mining has negative impacts on both humans and societies. It affects Indigenous peoples living in communities nearby silver mines in many ways.[34] Silver mining puts a significant amount of mental stress on indigenous workers due to the long hours of work, rough working conditions, repetitive nature of the work, roster schedules, and potential job loss.[34]

The use of addictive substances is also an active concern amongst indigenous workers. When income increases, workers are more likely to purchase alcohol and binge drink. This leads to a variety of social and health effects such as cirrhosis of the liver, brain damage, and fetal alcohol syndrome.[34]

Silver mining operations in indigenous communities lead to increased hunting pressure and a decline in traditional practices due to population growth and better hunting technologies. This affects local animal populations and cultural rituals.[34] Employment in mines results in longer working hours, reducing time for traditional activities like hunting and fishing, which threatens the spreading of ecological knowledge and cultural practices.[34] While mining can provide economic resources for purchasing hunting equipment, it also accelerates the decline in traditional lifestyles and cultural heritage, impacting food security and community cohesion in indigenous populations.[34]

Mining projects also pose significant threats to family integrity, manifesting in decreased quality and quantity of family time due to long working hours and associated stressors, as well as disruptions to traditional familial roles and responsibilities.[34] Limited time for communication and support may exacerbate existing problems within families. This leads to fragmentation and potential conflicts, with spouses having increased household responsibilities and children facing adverse consequences such as behavioral issues and academic struggles.[34]

Silver mining in indigenous communities lead to cultural shifts, with Western values often replacing traditional ones. While some argue that mining can promote cultural values such as independence and pride through job creation and increased disposable income, others highlight negative impacts such as the loss of traditional languages, attributed to factors like migration, labor market participation, and lack of educational support.[34]

See also

- Silver mining in the United States

- Global silver trade from the 16th to 19th centuries

- Spanish treasure fleet

- Spanish Silver Train

- Royal fifth

- Patio process

References

- ^ a b c Etris, S. F. (2010). "Silver and Silver Alloys". Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology. pp. 1–43. doi:10.1002/0471238961.1909122205201809.a01.pub3. ISBN 978-0471238966.

- ^ Debnam, Andrew, 2021. Silver. Mindat.org https://www.mindat.org/min-3664.html

- ^ "Silver: A native element, mineral, alloy, and byproduct". geology.com. Retrieved 2024-02-13.

- ^ Bevan, J., Clark, A., & Symes, R., The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Mineral Kingdom: Chapter 5: The Mineral Kingdom. Hamlyn, Toronto, 1978. ISBN 0-600-36263-9.

- ^ Kassianidou, V. 2003. Early Extraction of Silver from Complex Polymetallic Ores, in Craddock, P.T. and Lang, J (eds) Mining and Metal production through the Ages. London, British Museum Press: 198–206

- ^ a b Reddy, Rohan (2022-06-09). "Silver, Explained". Global X ETFs. Retrieved 2024-02-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Hilliard, Henry E., 2003. "Silver". USGS.

- ^ Scott, D., & Williams, T, 1994. Investigation of a rock-burst site, SunshineMine, Kellogg, Idaho. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/mining%5C/UserFiles/works/pdfs/irbs.pdf

- ^ Medical Letter on the CDC & FDA (18 October 2020). "Mexico Silver Mining Is Flourishing with New High Grade Silver Discoveries". Gale Academic: 1991.

- ^ Australia precious metals mining market (gold, silver, diamond) growth and forecasts to 2020. 2014. M2 Presswire, June 26, 2014. ProQuest 1540231009

- ^ United States silver mining market overview and forecast to 2020: Trends, fiscal regime, major projects, and competitive landscape. 2012. M2 Presswire, November 20, 2012. 1171392860

- ^ "pg. 152 – Silver" (PDF). USGS. 2016. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

- ^ CPM Group (2011). The CPM Silver Yearbook 2011. New York, NY: Euromoney Books. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-9826741-4-7.

- ^ CPM Group (2011). The CPM Silver Yearbook 2011. New York, NY: Euromoney Books. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-9826741-4-7.

- ^ "43-101 Preliminary Economic Assessment Technical Report Malku Khota" (PDF). South American Silver Corp. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c "10 Biggest Silver Mining Companies". Investopedia. Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Silver Mining in History |". Retrieved 2024-04-10.

- ^ Wood, J. R.; Hsu, Y-T.; Bell, C. (2021). "Sending Laurion Back to the Future: Bronze Age Silver and the Source of Confusion" (PDF). Internet Archaeology. 56 (9). doi:10.11141/ia.56.9. S2CID 236973111.

- ^ "Datahub of ERC funded projects". erc.easme-web.eu. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ "Silver and the Origins of the Viking Age: An ERC project". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ "..The Silver Treasure | KODE..." kodebergen.no. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ "Viking Ireland | Archaeology". National Museum of Ireland. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

- ^ History, Scottish; read, Archaeology 15 min. "The Galloway Hoard in the context of the Viking-age". National Museums Scotland. Retrieved 2021-10-19.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Satyanarayana, Dr. D.N.V. (July 2018). "Recovery of Silver from X Ray Waste From Electro Deposition" (PDF). International Journal of Latest Technology in Engineering. 7 (7).

- ^ Dan Oancea: Low Sulphidation Epithermal Vein Deposits http://technology.infomine.com/articles/1/546/silver.sulphidation.epithermal/silver.deposits.–.aspx

- ^ Nicholas A. Robins, Mercury, Mining, and Empire: The Human and Ecological Cost of Colonial Silver Mining in the Andes. Bloomington: Indiana University Press 2011. https://doi.org/10.1093/envhis/ems086

- ^ "Country name - The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 2024-02-09.

- ^ Dan Oancea: Silver Deposits - Carbonate Replacement Deposits http://technology.infomine.com/articles/1/693/silver.deposits.crd/silver.deposits.carbonate.aspx

- ^ Gillerman, Virginia (December 4, 2019). "Idaho Mining and Exploration, 2019"(PDF). Idaho Geological Survey. Retrieved April 23, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Lacerda, L. D. (1997-07-01). "Global mercury emissions from gold and silver mining". Water, Air, and Soil Pollution. 97 (3): 209–221. Bibcode:1997WASP...97..209L. doi:10.1007/BF02407459. ISSN 1573-2932.

- ^ a b Nriagu, Jerome, 1994. Mercury pollution from the past mining of gold and silver in the Americas. Science of the Total Environment, Volume 149, Issue 3, Pages 167-181, ISSN 0048-9697, https://doi.org/10.1016/0048-9697(94)90177-5.

- ^ Castro, Sergio H; Sánchez, Mario (March 2003). "Environmental viewpoint on small-scale copper, gold and silver mining in Chile". Journal of Cleaner Production. 11 (2): 207–213. Bibcode:2003JCPro..11..207C. doi:10.1016/s0959-6526(02)00040-9. ISSN 0959-6526.

- ^ Esteller, M.V., Domínguez-Mariani, E., Garrido, S.E. et al. Groundwater pollution by arsenic and other toxic elements in an abandoned silver mine, Mexico. Environ Earth Sci 74, 2893–2906 (2015). doi:10.1007/s12665-015-4315-9

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gibson, Ginger; Klinck, Jason (2005). "Canada's resilient north: the impact of mining on aboriginal communities" (PDF). Pimatisiwin: A Journal of Aboriginal and Indigenous Community Health. 3 (1): 115–140.